As the demand for accountability in health care increases, monitoring the outcomes of treatment has become an increasingly important goal

(1). Although practical difficulties, including cost, have limited the full realization of this goal

(2,

3), some very large health care organizations, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), now maintain databases that provide meaningful outcomes monitoring data as originally envisioned by Ellwood

(4).

With the advent of the new class of atypical neuroleptics, there has been much interest in evaluating the “real-world” effect of their use on relevant outcomes. Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that the atypical neuroleptics olanzapine

(5), risperidone

(6), quetiapine

(7), and clozapine

(8–

10) are as at least as efficacious, and perhaps more efficacious, than the older, typical neuroleptics in controlled studies. However, to our knowledge, no studies have compared these medications in naturalistic, real-world practice (i.e., outside the constraints of a research study).

Assessment of changes in health status associated with a specific intervention, such as prescription of an atypical neuroleptic in a real-world setting, is critically important in evaluating treatments that must inevitably compete for scarce resources. Thus far, however, only a few studies have evaluated interventions using data from large-scale outcome monitoring efforts. These studies include evaluations of work therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(1) and of the role of clozapine in preventing suicide

(11) and inpatient rehospitalization

(12).

At the beginning of fiscal year 1998, VA mandated that every mental health outpatient receive a Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score every 90 days as part of an initiative to document the outcomes of VA mental health care

(13). The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale is widely thought to be the most commonly employed clinical rating scale in practice

(14), and it is included as axis V in the multiaxial diagnosis described in DSM-IV. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale provides a summary score reflecting the level of psychological, social, and occupational functioning on a scale from 1, persistent and extremely severe difficulty in functioning, to 100, superior functioning in every domain, with brief anchoring descriptions at every 10-point increment. It represents an evolution of a scale whose previous versions were described by Luborsky

(15) and in DSM-III-R.

The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale is an easily administered scale with the potential for good interrater reliability under research conditions

(16) and at least moderately good interrater reliability under clinical conditions

(17). Some researchers have raised concerns that the scale scores seem to be more closely associated with symptom severity than with levels of social or occupational functioning, although patients’ demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and marital status, do not appear to be significant confounding factors

(14). Thus, while the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score is only a single, subjectively evaluated item on a scale that is not well operationalized and has anchors for only every tenth value, it is an easily scored summary assessment of global mental health status. Scores on the scale have been correlated with both functional capacity and symptom severity

(14), which are highly salient outcomes in the assessment of treatment effectiveness.

This study used national VA administrative databases to examine changes in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores associated with the use of atypical neuroleptics in a large group of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The study examined changes in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale ratings, both in patients who continued taking the same neuroleptic over a 1-year period and in those whose neuroleptic was changed. In addition, among patients whose neuroleptic was switched, changes in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale ratings associated with switching to each of the atypical neuroleptics commercially available in 2000 were also examined.

Method

Sample

All VA outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia treated from October 1, 1998, to September 30, 1999 (fiscal year 1999), were identified by using an operational definition that required at least two outpatient encounters in a specialty mental health outpatient clinic with either a primary or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (corresponding to DSM-IV codes 295.00–295.99).

Next, all records of prescriptions filled by these patients within the VA system from June 1, 1999, through September 30, 2000, were obtained from the VA Drug Benefit Management System in Hines, Illinois. Since intramuscular neuroleptics are frequently administered without a record of the corresponding prescription being entered in the system, only prescriptions for oral medications were included in the analysis. All patients who experienced no change in oral neuroleptic monotherapy (although dose could vary) during the 3 months from June through August 1999 were identified. Patients who received prescriptions for multiple neuroleptics were excluded from further analyses.

The records of these outpatients, who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and were stably treated with oral neuroleptics, were then merged with administratively available Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores from two periods of time: 1) June through August 1999 (the baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale rating in the stable medication period) and 2) from October 1, 1999, to September 30, 2000 (the subsequent fiscal year, fiscal year 2000). In addition, for patients whose neuroleptic medication was switched, the second Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score had to be recorded at least 30 days after the date of the medication switch. Thus, the analytic sample included VA patients with 1) two outpatient visits with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, 2) 3 months of receiving the same oral antipsychotic agent during the initial stable medication period, and 3) complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data from both the stable medication period and the follow-up period.

Since the VA had recently initiated a policy of recording Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores for psychiatric outpatients every 3 months, the study period represents the first full year that this directive was in effect. As a result, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale assessments were not available for all patients. Analyses comparing patients with complete data to those without complete data were conducted to evaluate sampling biases.

Measures

Data describing patient characteristics such as age, income, gender, race/ethnicity, receipt of VA compensation or pension, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, outpatient and inpatient service utilization, and zip code of the patient’s residence were also obtained from VA workload databases. The distance to the nearest VA hospital from the centrum of the district designated by the zip code of residence was calculated for each patient

(18).

Prescription records from the VA Drug Benefit Management System were then obtained to classify patients into five subgroups on the basis of which neuroleptic they had received during the 3-month stable medication period: clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or any conventional neuroleptic.

The Drug Benefit Management System prescription data were then examined for the subsequent year (fiscal year 2000). Patients who received a prescription for a different neuroleptic during the next year were distinguished from those who continued to receive the same neuroleptic. The patients whose medication was switched were also characterized by the type of neuroleptic they received after their medication was switched.

Analysis

First, because suitable Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data were available for only a subset of the sample, we used logistic regression to evaluate how patients in the analytic sample differed from the entire VA patient population with a stable medication period. Second, we used analysis of variance to compare both baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores and change in scores between patients who continued to receive the original neuroleptic and those whose medication was switched during the subsequent year. In the analyses of change in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, the dependent variable was the difference between the last score for the subsequent year and the last score for the stable medication period. Since patients whose medication was switched are likely to differ from those who continued to receive the same medication on various sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, potentially confounding factors were included as covariates. The covariates included baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score; the number of days between the baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale rating and the follow-up rating; income; age; race; gender; comorbid dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, PTSD, personality disorder, other psychotic disorder (delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified [DSM-IV 297.00–299.99]), substance abuse, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or other affective disorder; and receipt of VA compensation. Dichotomous measures of hospital utilization (e.g., hospitalization for 1–18 days or more than 18 days) along with a five-level categorization of the number of mental health outpatient visits were also included in the model as covariates.

The second set of analyses was limited to patients whose medication was switched and examined differences in baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores and change in scores by the drug the patients received after their medication was switched. As in the previous set of analyses, we first evaluated how patients with complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data differed from those without complete data using logistic regression that included the variables listed as covariates in the preceding paragraph. Then, for the patients whose medication was switched, analysis of covariance was used to examine differences in baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores and change in scores according to the medication received after the switch in medications. In this analysis the dependent variable was the difference between the last Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score of fiscal year 2000 and the last score before the medication was switched. This analysis included as covariates the same potentially confounding measures that were included in the previous analyses.

Results

Overall Sample

A total of 14,408 outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia received the same oral neuroleptic monotherapy during the index stable medication period. Complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data were available for 9,066 of those outpatients (63%). Within the analytic sample, 96.8% (N=8,776) of the subjects were male, 71.1% (N=6,446) were Caucasian, 23.1% (N=2,094) were African American, 3.8% (N=345) were Hispanic, and 2% (N=181) were classified as “other” race/ethnicity. A total of 36.4% (N=3,300) of the patients in the analytic sample had a comorbid diagnosis of either major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, 20.7% (N=1,877) had alcohol or drug abuse, 17.0% (N=1,541) had an anxiety disorder or adjustment reaction, 12.6% (N=1,142) had PTSD, 6.8% (N=616) had a personality disorder, and 6.7% (N=607) had dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Within this group, 13.6% (N=1,233) received VA compensation with a disability rating of 10%–50%, and 46.9% (N=4,252) received compensation with a disability rating of 60%–100%. The patients in the analytic sample were a mean of 51.7 years old (SD=11.4), had a mean income of $14,746 (SD=$16,467), and lived a mean of 27.3 miles (SD=106.4) from the nearest VA facility. In the previous year they had a mean of 40.9 outpatient mental health and substance abuse visits (SD=83.6); 11.4% (N=1,033) had been hospitalized for between 1 and 18 days, and 11.8% (N=1,070) had been hospitalized for more than 18 days. Their last mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale rating during the stable medication period was 49 (SD=13). The anchor point description for the rating interval of 40–50, as shown in DSM-IV, is “serious symptoms (e.g., suicidal ideation, severe obsessional rituals, frequent shoplifting) OR any serious impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning (e.g., no friends, unable to keep a job).”

Patients with complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data (N=9,066) were significantly different from those without complete data (N=5,342) in having more outpatient visits (χ2=56.49, df=4, p<0.0001), in living farther from the hospital (χ2=18.07, df=1, p<0.0001), and in being more likely to have a comorbid diagnosis of PTSD (χ2=4.41, df=1, p<0.04) or personality disorder (χ2=6.01, df=1, p<0.02) and to have been hospitalized in the previous year for either 1–18 days (χ2=4.70, df=1, p=0.03) or more than 18 days (χ2=34.56, df=1, p<0.0001).

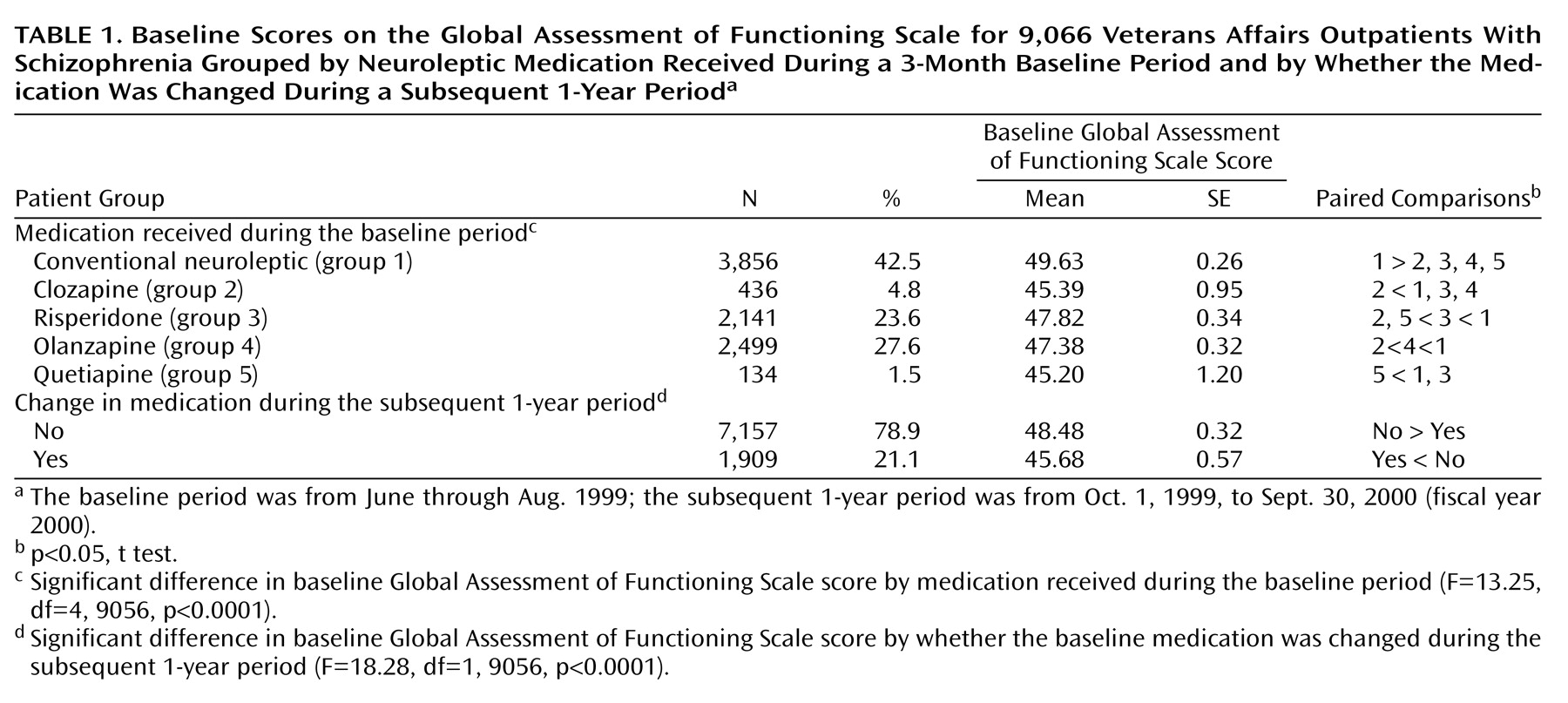

Baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores for patients grouped according to the medication that was prescribed during the stable period are shown in

Table 1. Patients who received conventional neuroleptics had a significantly higher mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score than any of the other medication groups, while patients who received clozapine and quetiapine had the lowest, presumably because these drugs were used for patients with more refractory symptoms. Significant differences in the mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores between the five groups are identified in

Table 1.

Comparison of Patients With and Without a Medication Switch

In the year after the index period, 7,157 (78.9%) patients continued to receive the same neuroleptic they had received during the stable medication period, while 1,909 (21.1%) had a switch in medications. Those who continued to receive the same medication had significantly higher mean initial Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores than those whose medication was switched (F=18.28, df=1, 9056, p<0.0001). Furthermore, patients without a medication switch showed significantly greater improvement (mean change=0.27, 0.6%) than patients whose medication was switched (mean change=–1.71, –3.7%) (F=9.19, df=1, 9035, p<0.002), most likely because patients who had medication changes after the stable medication period had been experiencing clinically significant problems, which continued to some extent, even though there was a change of neuroleptic.

Among patients whose neuroleptic medication was switched, the mean number of days elapsed between the medication switch and the follow-up Global Assessment of Functioning Scale rating was 189 days (SD=90).

Changes in Functioning Score by Drug Received After Medication Switch

Among all patients whose medication was switched (N=2,983), 1,909 (64%) had complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data. Among all patients whose medication was switched, those with complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data differed from those without complete data in having significantly more outpatient visits (χ2=56.49, df=4, p<0.0001), having significantly more income (χ2=4.57, df=1, p<0.03), living farther from the hospital (χ2=8.81, df=1, p=0.003), and being more likely to have been hospitalized for 1–18 days (χ2=20.83, df=1, p<0.0001).

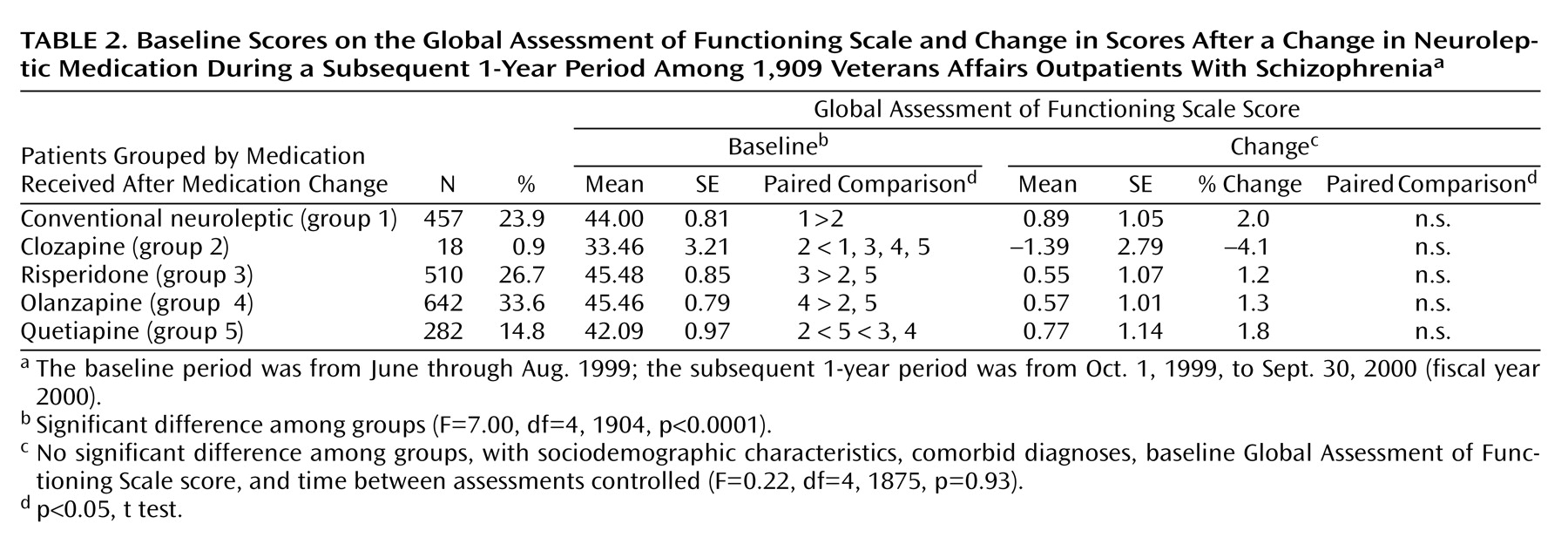

Among patients with complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data whose medication was switched (N=1,909), those who went on to receive risperidone and olanzapine had the highest Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores before the medication switch, while those who eventually received clozapine had the lowest. With baseline drug category and other potentially confounding covariates controlled, no significant differences were found in the mean change in the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score across patient groups identified by the medication received after the switch (

Table 2).

Discussion

This study used administratively available Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores to examine the effect of newly initiated treatment with atypical neuroleptic medication in a large sample of patients with schizophrenia treated within the VA health care system throughout the United States. Several findings deserve mentioning. First, the patients whose data were analyzed—those who had no change in oral neuroleptic medication during the 3-month index period—were functioning with severe to moderate symptoms and/or dysfunction. Second, there were significant differences in baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores between patients who were receiving different neuroleptics. That patients treated with clozapine and quetiapine had the lowest Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores is consistent with the indication for use of clozapine in patients with refractory symptoms and with the likelihood that quetiapine, the newest neuroleptic at the time, may have been tried in patients for whom other available agents had proven ineffective. The observation that patients who were receiving typical neuroleptics had the highest Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores is consistent with the likelihood that, in the years after the introduction of the atypical neuroleptics, patients who continued to take typical neuroleptics were those who were most responsive to the older agents.

Third, after the initial period of stable neuroleptic prescription, a total of 1,909 of the 9,066 patients (21%) with complete Global Assessment of Functioning Scale data had their neuroleptic medication switched in the subsequent 1-year period. Despite differences in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores at the time of the medication switch, once potentially confounding variables were controlled, no significant differences were found in subsequent changes in the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score between any of the medication classes—conventional neuroleptics, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine—during a follow-up period that averaged approximately 6 months in length. Earlier studies have suggested that for the great majority of patients, improvements are clinically manifest within the first several months and certainly within the first 6 months of treatment

(19,

20). Our findings suggest that, in real-world conditions, none of the atypical or conventional neuroleptics resulted in a significantly greater improvement in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores than any of the others.

The lack of a difference between any of the medication groups in change in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores is consistent with several reports. In a meta-analysis of 52 clinical trials, no unique benefits in terms of efficacy or tolerability were observed for any of the atypical antipsychotics when compared with either the other available atypical neuroleptics or moderate to low doses of typical antipsychotics

(21). In a review of studies comparing olanzapine and risperidone with haloperidol, no significant differences between the two atypical neuroleptics were demonstrated in measures of efficacy

(22).

Furthermore, even when medications are found to have different rates of efficacy in some highly controlled trials, the transition from randomized clinical trials to real-world practice, and across clinical subgroups, frequently is accompanied by a decrease or total loss of statistically significant effect. For example, in the first report documenting the superiority of clozapine to a typical neuroleptic (chlorpromazine), inpatients meeting rigorous diagnostic and severity criteria received the two medications for 6 weeks with a completion rate of nearly 90%

(8). In contrast, a trial that followed inpatients randomly assigned to receive haloperidol or clozapine for 1 year in a variety of VA outpatient clinics found much smaller, although still significant, differences on symptom measures

(9). A third trial that compared clozapine and the doctor’s choice of conventional medication in long-term state hospital patients found no significant differences in symptom changes

(10). Thus, as one moves across subgroups and from more artificial to more naturalistic settings, differences in effectiveness appear to become attenuated. Our findings are consistent with these studies, whether the explanation is that these medications are not truly different in their efficacy or that differences in efficacy are obscured in the more complex setting of real-world practice.

Several limitations in the study methods deserve mention. First, patients were not randomly assigned either to have their medications switched or to receive one of the various atypical neuroleptics, and subgroups that received different treatments are likely to have been different from each other in important ways. For example, patients whose medication was switched to clozapine or to quetiapine (the newest atypical neuroleptic available at the time of this study) had lower Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores than other patients and were probably selected to receive these medications because they had refractory symptoms or overall poor functioning. Such differences could affect the amount of observed change in the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score. We addressed these differences by including the baseline Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score and other clinical variables as covariates in all subsequent analyses. The possibility of bias remains in this study, as in all nonexperimental research. Studies of real-world practice will always have to contend with the possibility of selection bias.

Second, the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale is widely recognized as an imperfect outcome measure. Although its major advantages are its brevity and ease of administration, it is based on a single item, relies on the clinician’s subjective assessment, and has descriptive anchors for only one of every 10 rating points. However, as shown by Moos et al.

(14), it is significantly associated with salient indicators of mental health status such as psychiatric symptoms and social and occupational functioning. In the study of real-world practice in large health care systems, tradeoffs between the costs, feasibility, and psychometric strength of the measures used are inevitable.

Third, the sample consisted entirely of veterans who were older than the general population, and almost all of the veterans in the sample were male. Only patients who were taking oral antipsychotic monotherapy were included, and no information about compliance was available, making generalizability to other groups uncertain.

A fourth limitation is that in large samples, such as that used in this study, statistically significant differences may have limited clinical importance. To our knowledge, there is no standard for establishing the magnitude of a clinically meaningful change in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score. However, a randomized clinical trial comparing clozapine and haloperidol

(9) that showed significant differences between these agents for standardized ratings with instruments such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

(23) also showed that a change of 2.2 points in the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale constituted a significant difference in favor of clozapine. Thus, differences of the magnitude reported in this study can reflect differences that are generally taken to be clinically meaningful.

Finally, complete information on Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores was available for only a subset of the patients. The main difference observed between those with and without complete information was that those with complete information had more service utilization. This difference would be expected, as the more often a patient is seen, the more likely complete information would be available for the patient.