Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are severe and often chronic eating disorders associated with high levels of physical and psychological comorbidity and poor quality of life. A unique feature of anorexia nervosa patients is their high mortality, which is twice that of other psychiatric inpatients. Eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa, also pose a financial burden, with the cost of treatment similar to that of the most severe psychiatric disorders

(1).

Despite the serious nature of these disorders, there is a prevailing view among medical professionals that eating disorders are not genuine illnesses

(2). Many health professionals hold stigmatizing attitudes toward eating disorders, based on the belief that they are self-inflicted

(3). Compared to patients with diabetes, obesity, or schizophrenia, those with eating disorders are less well liked by medical and nursing staff—including psychiatrists

(4,

5).

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the view of eating disorders as trivial and self-inflicted has contributed to a bias in publication rates of articles with related topics in leading journals in recent years. We assessed this by comparing the number of published articles about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa with those of disorders of equivalent disease burden.

Method

We used disability-adjusted life-years, which measure the total impact of fatal and nonfatal outcomes, to identify disorders of comparable disease burden to anorexia nervosa and/and bulimia nervosa. Data were taken from the Australian Burden of Disease and Injury Study

(6), since the leading causes of disease burden in Australia are similar to those for other established market economies. The disability-adjusted life-years for eating disorders were reported as 11,176 (5,835 disability-adjusted life-years for anorexia nervosa and 5,340 disability-adjusted life-years for bulimia nervosa). Two anxiety disorders had a comparable disease burden: panic disorder (5,592 disability-adjusted life-years) and agoraphobia (4,600 disability-adjusted life-years), with a total of 10,192 disability-adjusted life-years.

We compared the number of articles about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa with those about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia. A review was conducted of all articles between February 1996 and March 2001 that were published in the 10 highest-impact psychiatric, psychological, and medical journals. These were found from a search of the 1999

Journal Citation Reports, Science Edition (Institute for Scientific Information) with the subject headings “psychiatry,” “psychology,” and “medicine, general and internal.”

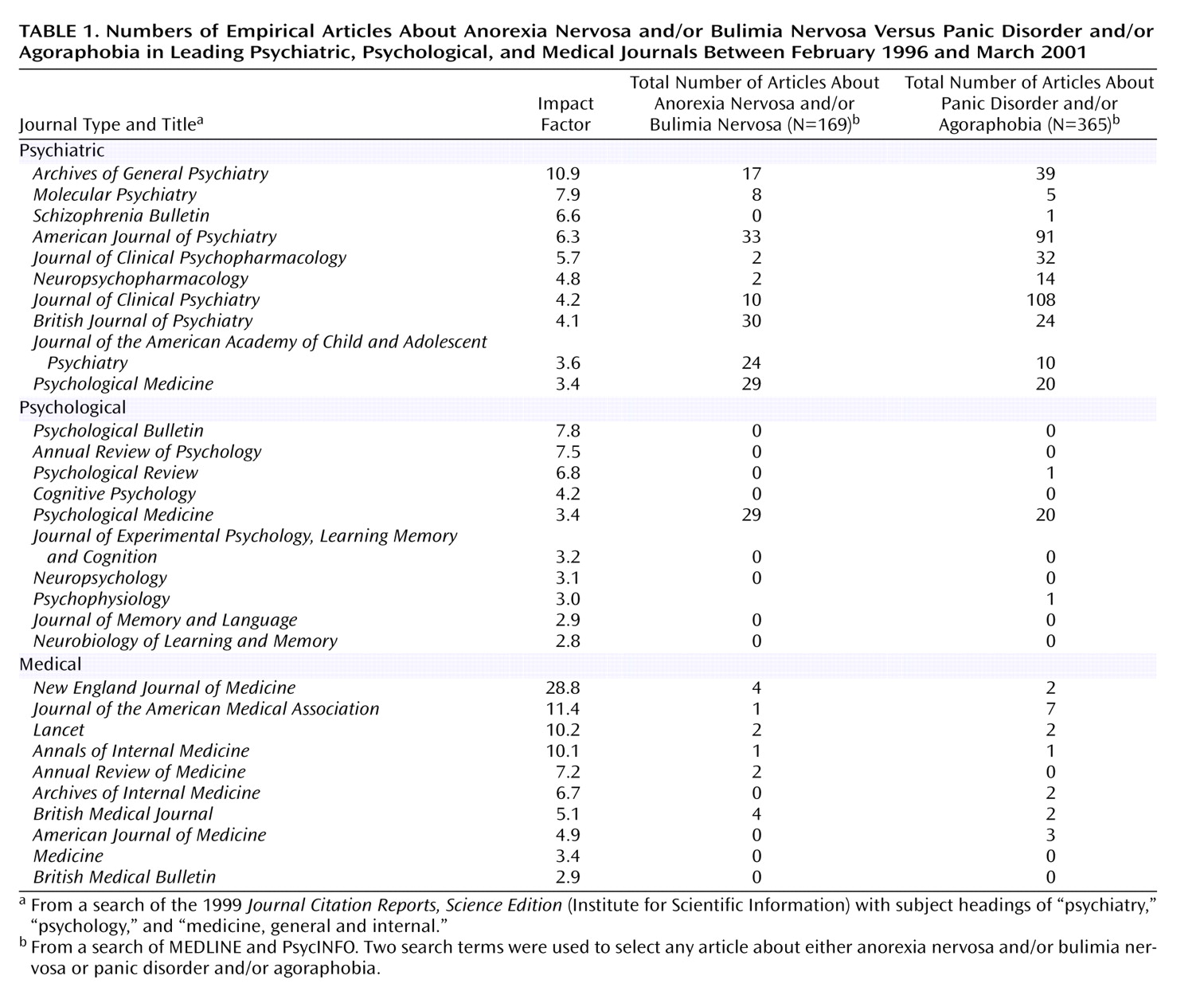

Table 1 shows the 29 journals reviewed and their impact factors (one journal was listed twice as one of the 10 most-cited journals for psychiatry and psychology).

Articles about anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, and agoraphobia were searched by using two databases, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. Two search terms were used to select any article about either anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa (“anorexia nervosa OR bulimia nervosa”) and panic disorder and/or agoraphobia (“panic disorder OR agoraphobia”). The “or” operator employed is an inclusive term and searches for articles that contain any of the query terms (e.g., any articles referring to anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, including articles referring to both). A total score of the number of articles about each topic was computed for each journal, excluding letters, comments, editorials, and duplicated articles across databases.

To investigate whether there is an acceptance bias against articles about eating disorders among high-impact journals, all 29 journals were contacted for information about their numbers of articles about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa and panic disorder and/or agoraphobia submitted, accepted, and rejected between 1996 and 2001.

Results

Table 1 shows the results of the journal review. Between February 1996 and March 2001, a total of 169 empirical articles were published about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa in the highest-impact psychiatric, psychological, and medical journals. This compares with 365 empirical articles published about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia. We excluded letters, comments, and editorials, of which there were 64 about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa and 86 about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia.

The majority of the articles were published in the high-impact psychiatric journals: 131 of the 169 articles about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa and 334 of the 365 articles about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia. There were no articles published in the highest-impact psychological journals about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa between 1996 and 2001, and only one article was published about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia during that time.

Of the 29 journals approached for submission and acceptance rates between 1996 and 2001, 21 responded. Ten journals recorded this type of information, and 11 did not. The submission rate was generally low for articles regarding these disorders. Four journals received no articles about anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, or agoraphobia. Three journals received five or fewer articles about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa and none about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia. One journal received one article about panic disorder and none about anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or agoraphobia, and one journal received one article about anorexia nervosa and one article about panic disorder. The one exception was the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, which received 60 articles about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia (and accepted 45) and five articles about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa (and accepted three). Unfortunately, three of the journals with the biggest differences in the numbers of eating disorders and anxiety disorders articles did not respond to our request, and the limited data meant we were unable to determine whether there is an acceptance bias.

Discussion

Our survey of leading journals found that, between 1996 and 2001, there were nearly twice as many articles published about panic disorder and/or agoraphobia than about anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa, despite the disorders’ comparable disease burden. Two of the journals included were psychopharmacology journals. Drug treatments are currently not commonly used in the treatment of anorexia nervosa; thus the likelihood of articles about anorexia nervosa being submitted to these journals was low. However, even if these two journals were excluded from the count, the nearly 2:1 ratio between anxiety and eating disorders articles published in leading journals remains intact.

Given the dearth of information about ratios of submitted to accepted articles regarding the two types of disorders, two basic possibilities need to be considered in trying to explain this finding. One possibility is that the ratio of submitted to published articles regarding both groups of disorders is similar but that fewer eating disorders articles than anxiety disorders articles are being submitted to top journals. This could be the result of fewer research studies being carried out about eating disorders than about anxiety disorders, perhaps because less funding is available. However, when we searched the U.S. National Institute of Health’s Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects database (http://crisp.cit.nih.gov) to ascertain the numbers of projects funded as a crude indicator of potential funding discrepancies, we found a similar number of grants funding agoraphobia and/or panic disorder research (N=238) as for anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa research (N=200) for the 5-year period covered by our study. Alternatively, eating disorder researchers may believe that their chances of getting their articles published in high-quality journals are limited and therefore do not submit their articles to such journals. In particular, it may be that these authors preferentially submit their articles to one of the specialty eating disorders journals. However, there are also specialist anxiety disorders journals, and on the face of it, the opportunities for submitting articles to specialty journals seem comparable across the two types of disorders.

A second possibility is that the numbers of articles submitted for the two groups of disorders is similar but a higher proportion of the eating disorders articles are rejected. This could be because the eating disorders articles are generally of poorer quality, which seems rather unlikely. More likely, our findings may indicate a bias against research into eating disorders among some of the leading psychiatric journals. This may reflect editors’ and reviewers’ negative attitudes toward these disorders, possibly viewing them as unimportant for the general psychiatrist compared to anxiety disorders, which are seen as “bread-and-butter” psychiatry. The fact that anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are predominantly female disorders compared to the more equal sex distribution of panic disorder and agoraphobia may contribute to the view that eating disorders are of lesser importance.

In summary, the question of whether top journals are biased against studies of eating disorders cannot be conclusively answered by our study but deserves further attention. We recommend that all generalist journals monitor the ratio of submitted to published articles concerning particular topics in order to avoid the possibility of discriminating against particular disorders.