Perfectionism is a salient trait in women with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa during acute illness

(1,

2) and after recovery

(3–

5). Premorbid perfectionism may also be a risk factor for anorexia nervosa

(6). These factors, together with reports of heritability estimates for perfectionism subscales ranging from 22% to 42% (unpublished paper by F. Tozzi et al.), suggest that perfectionism may be a risk factor for eating disorders and an endophenotype for genetic studies

(2). Perfectionism may act in concert with low self-esteem or body dissatisfaction

(7,

8).

The optimal definition of perfectionism is unclear. Several authors recommend using multidimensional scales rather than a global perfectionism score

(9; unpublished study by F. Tozzi F et al.). The goal of the present study was to explore the association between components of perfectionism and seven common psychiatric disorders in a population-based sample of female twins and to determine the extent to which aspects of perfectionism are associated with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

Method

Female-female twin pairs born from 1934 to 1974 from the population-based Virginia Twin Registry

(10) participated in this study. These twins were interviewed four times between 1988 and 1997.

In 1999, questionnaires were mailed to all previous participants in the female-female twin study and a parallel male-male and opposite-sex twin study

(11). Valid questionnaires were returned by 1,510 (49.5%) of 3,050 female twins. Limited resources prohibited follow-ups of nonresponders. Participants were all Caucasian, with a mean age of 42.5 years (SD=8.2). Final data were available for 1,010 members of female-female twin pairs who had returned the questionnaire and who had diagnostic information from previous interviews.

The questionnaire included 12 items from the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale

(12). The original Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale includes six subscales: concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, personal standards, organization, parental criticism, and parental expectations. On the basis of previous research on the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale and communication with the scale developers, we included items focused on individual (rather than parental) characteristics. We chose four items each from the concern over mistakes and personal standards subscales that had shown reliable factor loadings in previous investigations

(12,

13) (the original doubts about actions subscale includes only four items). Items were not included from the organization subscale because it is thought that this scale does not capture a core component of perfectionism

(12).

Diagnostic data were available from previous interviews. Lifetime psychiatric and substance use disorders were diagnosed by using an adaptation of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(14) and DSM-III-R criteria with the following exceptions. First, we used broad definitions for several disorders—amenorrhea was not required for anorexia nervosa, and we eliminated the frequency and duration criteria for bulimia nervosa

(15,

16). Second, a 1-month rather than 6-month minimum duration of illness for generalized anxiety disorder was used

(17). Finally, diagnostic hierarchies were not used. The diagnostic algorithms, reliability, and interviewer training and qualifications are described elsewhere

(11,

17–21). Written informed consent was obtained before face-to-face interviews, and verbal assent was obtained before telephone interviews. The studies from which these data were obtained were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board and the Western Institutional Review Board.

We conducted logistic regressions using generalized estimating equations as operationalized in PROC GENMOD in SAS

(22) to control for the correlated nature of twin data. We conceptualized the seven binary psychiatric diagnoses as dependent variables and the standardized perfectionism subscale scores as independent variables. Given the high rates of comorbidity in individuals with eating disorders, all analyses of other disorders controlled for the presence of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

Results

Participation in this questionnaire was predicted by female gender (odds ratio=2.14, χ2=192.0, df=1, p<0.0001), older age (odds ratio=1.22 [per decade], χ2=82.1, df=1, p<0.0001), greater education (odds ratio=1.12 [per year], χ2=113.4, df=1, p<0.0001), and monozygosity (odds ratio=1.47, χ2=43.4, df=1, p<0.0001).

The prevalence of the seven psychiatric syndromes were 3.4% (N=34) for anorexia nervosa, 9.1% (N=92) for bulimia nervosa, 30.3% (N=306) for major depression, 16.6% (N=168) for alcohol abuse or dependence, 22.9% (N=231) for generalized anxiety disorder, 9.4% (N=95) for panic disorder, and 29.2% (N=295) for any phobia.

The correlations among the three perfectionism subscales were between concern over mistakes and personal standards (r=0.58), between personal standards and doubts about actions (r=0.29), and between doubts about actions and concern over mistakes (r=0.65).

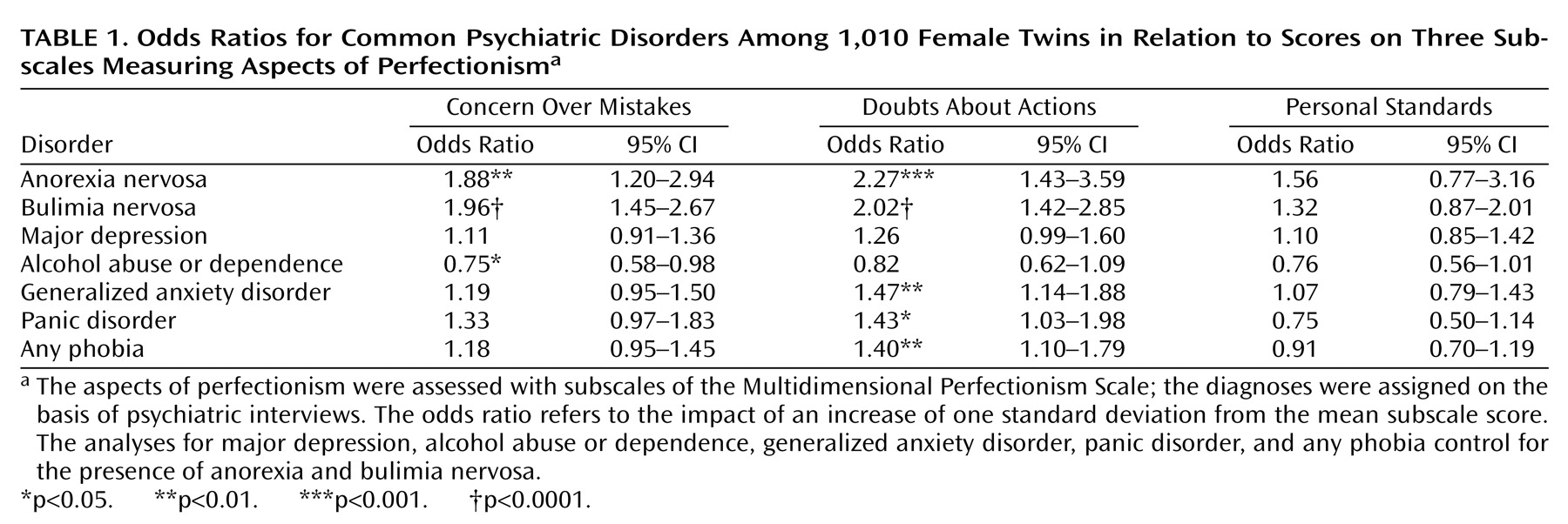

Table 1 shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the univariate logistic regression analyses. Concern over mistakes was uniquely associated with significantly elevated odds ratios for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and was protective against alcohol abuse or dependence. Doubts about actions was associated with both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa as well as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and phobia. There were no significant associations between any of the diagnostic categories and personal standards.

We then included concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and personal standards in two regression models to predict anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. With anorexia nervosa as the dependent variable, doubts about actions was a nonsignificant predictor of anorexia nervosa (beta=0.39, p=0.06). Concern over mistakes emerged as the only significant predictor of bulimia nervosa (beta=0.41, p=0.01).

Discussion

Confirming and extending previous clinically based knowledge, we found that elevated scores on a perfectionism scale—especially the aspect of perfectionism captured by the subscale for concern over mistakes—were significantly associated with the presence of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. This subscale measures negative reactions to mistakes and the tendency to interpret mistakes as failures. Concern over mistakes was not associated with elevations in any of the other psychiatric disorders assessed, although high scores were inversely associated with alcohol abuse or dependence. Multivariable regression models confirmed that, among the aspects of perfectionism that we measured, concern over mistakes and doubts about actions appear to be the most strongly associated with the presence of eating disorders.

High scores on the subscale for doubts about actions were more broadly associated with both eating and anxiety disorders, with high odds ratios for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, panic disorder, phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. This subscale measures doubts about the ability to accomplish tasks and obsessional aspects of perfectionism. The fact that high scores for doubts about actions were associated with both eating and anxiety disorders (and not major depression or substance use disorders) provides additional evidence for the relation between these two classes of disorders. Indeed, a high percentage of individuals with eating disorders report comorbid anxiety disorders

(23–

28), which tend to persist after recovery from eating disorders

(3–

5). In addition, there is evidence of shared genetic factors between eating and anxiety disorders

(29), and a unique genetic effect may contribute to symptoms of early eating and overanxious disorders (unpublished paper by J. Silberg and C. Bulik).

Previous investigations have shown that perfectionism is a salient clinical feature of both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Although prospective studies have not assessed whether elevated perfectionism is a prospective risk factor, its persistence after recovery has led some to suggest that it may be a trait risk factor for eating disorders (24; unpublished study by J. Silberg and C. Bulik). Our current results suggest that the observed association between perfectionism and eating disorders is not confined to clinical samples and that the aspect of perfectionism captured by scores on a subscale measuring concern over mistakes may be most strongly associated with eating disorders and not generally predictive of psychopathology.

Limitations of this investigation include that the data collection was not prospective and, therefore, the emergence of perfectionism may be a consequence of an eating disorder. There may be other disorders that we did not assess (e.g., obsessive-compulsive disorder or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder) that are also associated with perfectionism. In addition, our response rate was not optimal, although predictors of response did not differ from previous interview waves and were typical for twin studies

(30).