Juvenile mania has been a topic of considerable discussion and debate as the field grapples with how the diagnosis can be made reliably and validly

(1–

3) and whether (and how) the presentation of hypomania or mania may differ between children and adults

(4). In particular, there is considerable disagreement about the most appropriate diagnosis for children with a constellation of chronic and severe irritability, hyperactivity, and abnormal mood (usually sadness and/or anger). Some psychiatrists would give such children a diagnosis of “mixed mania” or rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, while others would not (1). To address this problem, a panel of experts recently recommended that researchers in the field define “narrow” and “broad” phenotypes for juvenile mania so that children meeting the criteria for each phenotype could be assessed systematically and followed longitudinally

(5).

The distinction between narrow and broad phenotypes is important from both a clinical and a research perspective. From the clinical perspective, it is important to know whether children who exhibit some manic symptoms respond to treatment differently than do those who meet the full diagnostic criteria for a manic episode

(6). From the research perspective, the distinction between narrow and broad phenotypes is important because pathophysiological and genetic studies require clearly defined inclusion criteria that will yield homogeneous groupings. This paper suggests a method for defining a range of phenotypes from narrow to broad, presents the rationale for the phenotype criteria, and outlines a research plan to validate the proposed phenotypic classification.

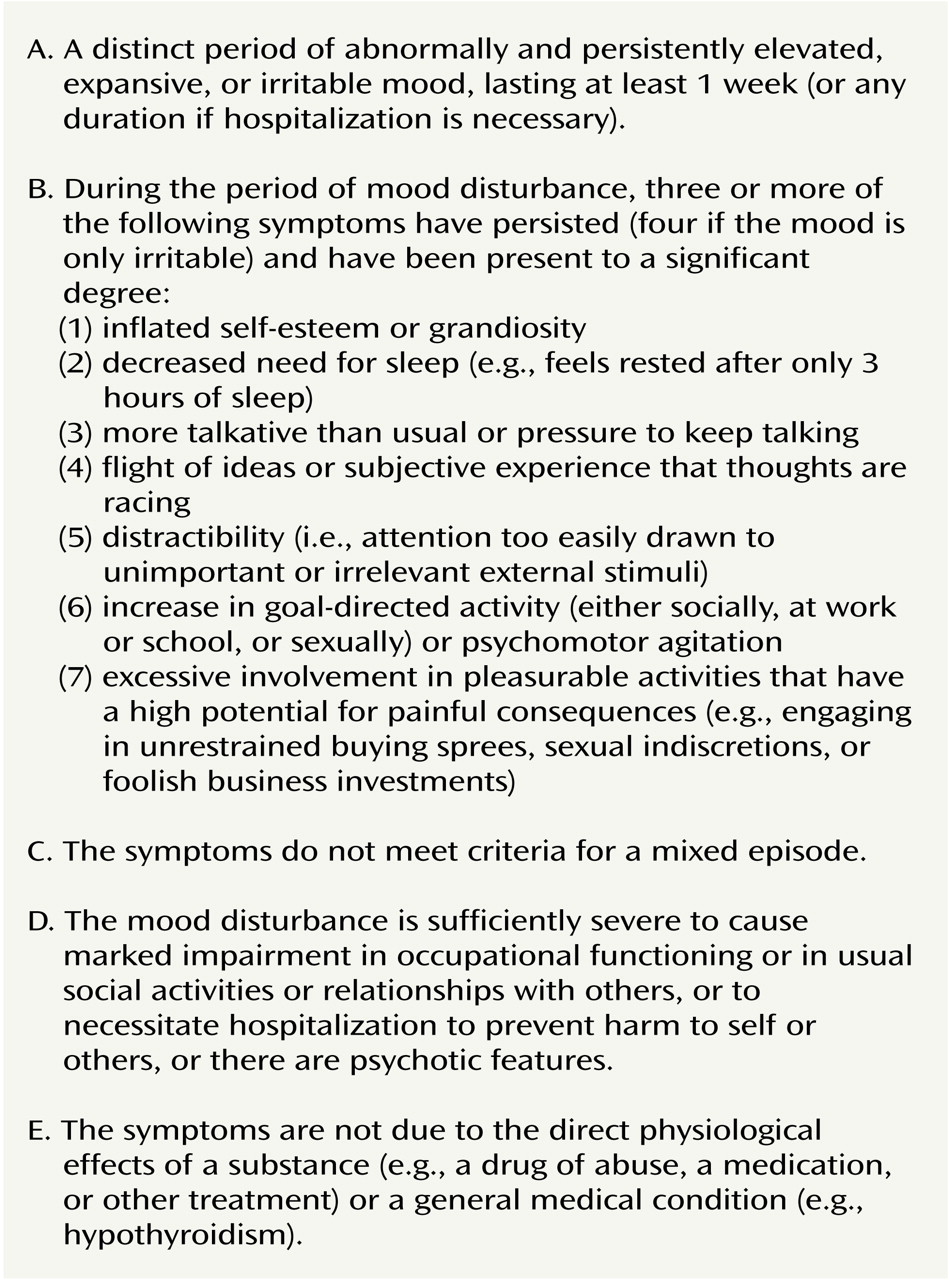

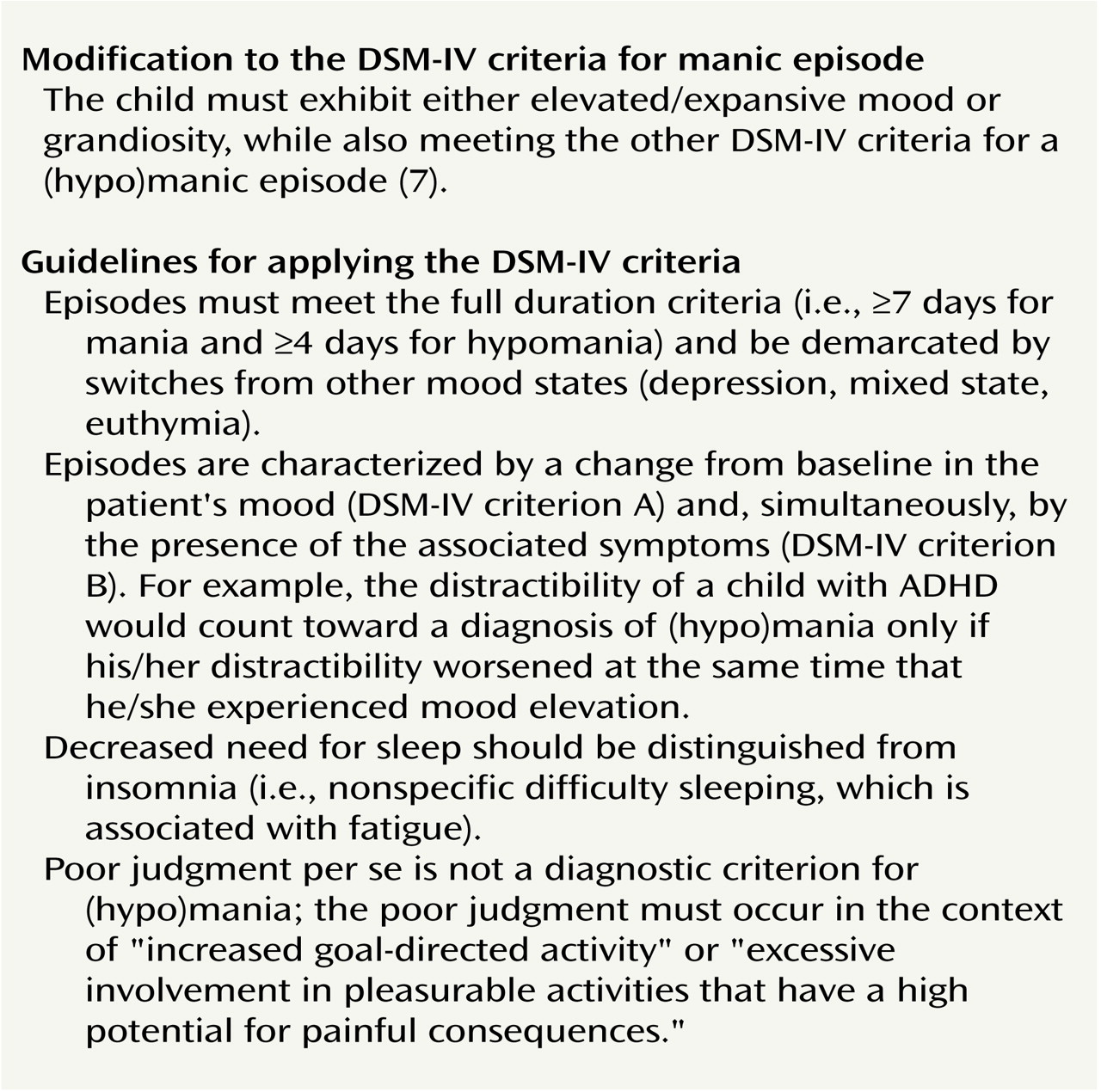

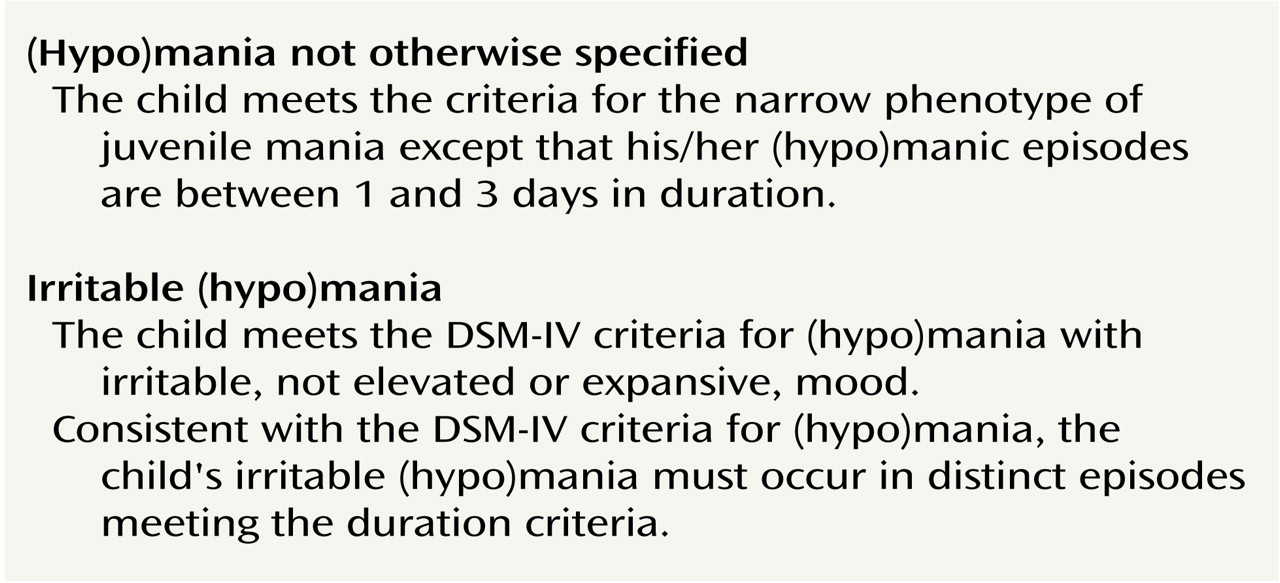

The controversy regarding the diagnosis of early-onset mania stems from disagreement on 1) whether the diagnosis of mania should require the presence of clearly defined episodes; 2) if so, what the minimum duration of these episodes should be; and 3) whether there are specific hallmark symptoms of mania that should be required for the diagnosis. In light of these questions, we suggest distinguishing four groups of children, only some of whom may ultimately suffer from an illness that is pathophysiologically similar to adult bipolar disorder. (In this phenotypic system, we follow DSM-IV

[6] in that the criteria for hypomania and mania differ in minimal episode duration [4 versus 7 days, respectively] and in level of impairment but are otherwise identical. Throughout this paper, we use the term “(hypo)mania” to denote “hypomania or mania.” The suggested phenotypes are 1) the narrow phenotype, exhibited by patients who meet the full DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for (hypo)mania, strictly construed, with the hallmark symptoms of elevated mood or grandiosity

(7,

8) and clear episodes meeting the duration criteria (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2); 2) two intermediate phenotypes, exhibited by patients who have a clearly episodic illness but fail to meet strict criteria for (hypo)mania either because their episodes are, by the DSM-IV criteria, too short (we have named this phenotype “[hypo]mania not otherwise specified”) or because they lack the hallmark (hypo)manic symptom of elevated mood (we have named this phenotype “irritable [hypo]mania”) (

Figure 3); and 3) the broad phenotype, exhibited by patients who have a chronic, nonepisodic illness that lacks the hallmark symptoms of (hypo)mania but that shares with the narrower phenotypes the symptoms of severe irritability and hyperarousal (

Figure 4).

Children exhibiting the broad phenotype may ultimately prove to be a heterogeneous group. Some may eventually meet the strict criteria for (hypo)mania; the course of others’ illness may be consistent with dysthymia, major depressive disorder, or some form of disruptive behavior disorder; and still others may prove to have a syndrome that is not well captured by the current diagnostic system. Family history may be a particularly important variable in defining more homogeneous subgroupings. For the present, we have defined a broad but clearly operationalized phenotype, identified by using the child’s symptoms, in order to facilitate the systematic study of children whose symptoms resemble those of the narrower phenotypes but whose nosologic status is unclear.

Longitudinal studies of children exhibiting each of the phenotypes are, of course, crucial. But ultimately the diagnosis of (hypo)mania, as of other psychiatric illnesses, will rest on an understanding of pathophysiology. At this point, when such understanding remains limited, careful phenomenological studies should inform the inclusion criteria for studies of brain function, and physiological studies should in turn yield data with implications for diagnostic criteria. In an attempt to facilitate this iterative process, we describe the proposed phenotypes while reviewing the problematic issues that complicate the diagnosis of (hypo)mania in children.

Narrow Phenotype: (Hypo)Mania (Full-Duration Episodes, Hallmark Symptoms)

As noted in the previous section, the most problematic issues in the diagnosis of juvenile mania involve questions about the presence and duration of episodes and the identification of hallmark symptoms of mania. Our narrowest phenotype requires that a child exhibit clear episodes that meet the full DSM-IV criteria, including duration (

Figure 1), and hallmark symptoms of mania (elevated/expansive mood or grandiosity)

(6,

7).

Figure 2 shows the criteria for the narrowest phenotype as well as guidelines for the application of the DSM-IV criteria for (hypo)mania. The requirement of clearly defined episodes stems from the fact that, since early descriptions of mania

(9), clinicians have observed that classic mania is characterized by demarcated time periods of disturbed mood accompanied by behavioral and cognitive symptoms. However, the controversy surrounding the diagnosis of mania in children has been fueled in large part by disagreement concerning the definition and minimum length of an episode

(1). In classic mania, manic episodes are discrete events long enough to be differentiated clearly from depressive and euthymic periods. Some investigators have argued that, while prepubertal children with mania have distinct episodes, these episodes are shorter than those of adults and remit less completely, so that fewer euthymic periods exist to demarcate affective episodes

(8,

10–13). Other investigators have described the presentation of early-onset mania as relatively chronic, with very brief episodes characterized by an acute but short-lived worsening superimposed on an impaired baseline

(1).

Several methodological and conceptual issues complicate the discussion of episodicity in childhood-onset mania and thus fuel the controversy. The first is that the available data are retrospective. Research has shown that adults perform poorly when asked to report retrospectively the duration and frequency of mood states, placing undue emphasis on the most recent and severe negative mood

(14). For children with psychopathology, data indicate that neither parents nor children can date reliably the onset of symptoms beginning more than a few months before the interview

(15). Thus, it may be extremely difficult for children with bipolar disorder, their parents, or even adults with bipolar disorder to give accurate retrospective reports of cycle length, since frequent mood switches occur in children (or adults) with bipolar disorder

(7,

16).

A second methodological issue concerns the tendency to characterize patients with affective episodes in terms of the longest episode(s) that they have ever experienced and/or in terms of the typical duration of their episodes. Studies of adults with bipolar disorder have tended to place greater diagnostic weight on the duration of a patient’s longest episodes. For example, the terms rapid, “ultra-rapid,” and “ultradian” cycling, often used to describe children with bipolar disorder

(10), are derived from the literature on adults with bipolar disorder

(17). In Dunner and Fieve’s original description of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder

(18), and in most subsequent research, the researchers required that adults with bipolar disorder experience four affective episodes that meet the full duration criteria in a year. We recommend that the same convention be used for children. It is noteworthy that Dunner and Fieve

(18) and subsequent researchers found that, in addition to having had full-duration episodes, most adult patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder also experienced shorter episodes.

In the literature on juvenile mania, however, researchers often do not specify the duration of the longest manic (or depressive) episodes patients have experienced. Such data would allow comparisons with adult patients. In addition, prospective longitudinal observation of children presenting with manic symptoms is an important complement to retrospective reports. Using both retrospective and prospective data, we found that most children with well-demarcated episodes and hallmark symptoms of mania have lifetime histories of episodes meeting full duration criteria (although most of their episodes are considerably shorter) and therefore may be categorized as having the narrow phenotype rather than as having (hypo)mania not otherwise specified (see the next section)

(19).

To be classified as having our narrowest phenotype, a child has to experience not only full-duration (hypo)manic episodes but also hallmark symptoms of (hypo)mania (elevated mood and/or grandiosity). While specificity is a serious problem in psychiatric nosology generally, and in childhood-onset disorders particularly, (hypo)mania is one of the few psychiatric illnesses that has a pathognomonic presentation: the episodic, hyperaroused, euphoric state

(20). However, some of the symptoms of (hypo)mania are nonspecific, and a major cause of the controversy regarding juvenile (hypo)mania stems from criterion overlap with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

(21). Such overlap is present in the following criteria: “pressure to keep talking” ([hypo]mania) and “often talks excessively” (ADHD), psychomotor agitation ([hypo]mania) and “often runs about or climbs excessively” (ADHD), and distractibility (both [hypo]mania and ADHD)

(6). To make the differential diagnosis with confidence, clinicians can rely on episodicity (since ADHD is not an episodic illness

[22]) and on the identification of symptoms that occur only in (hypo)mania.

Geller et al.

(8) found that grandiosity, elated mood, flight of ideas, decreased need for sleep, hypersexuality, and increased goal-directed activity (along with other symptoms not included in DSM-IV) differentiated children with bipolar disorder from those with ADHD. These univariate analyses should be complemented by multivariate techniques and receiver operating characteristics analyses

(23). In addition, longitudinal and family history data can contribute to the identification of cardinal symptoms of (hypo)mania. Prospective epidemiological studies could identify developmental norms for symptoms such as euphoria, grandiosity, and irritability, and clarify the extent to which childhood irritability predicts adult pathology.

The analysis by Geller et al.

(8) of symptoms differentiating youth with ADHD from those with bipolar disorder found that, of all the symptoms, elated mood and grandiosity were best able to distinguish the two groups. Therefore, in subsequent studies her research group required the presence of one of these classic symptoms of (hypo)mania for inclusion in the narrow phenotype group. We believe that this is a reasonable approach, and we have incorporated it into our definition of a narrow phenotype (

Figure 2). However, in applying this criterion, it is important to note that, just as depressed children may report sadness when their parents are aware only of the child’s irritability, the parents of (hypo)manic children may be aware of the child’s irritability but not of his/her concurrent euphoria. Therefore, it is important to interview both the parent and the child to ascertain the presence of elevated mood.

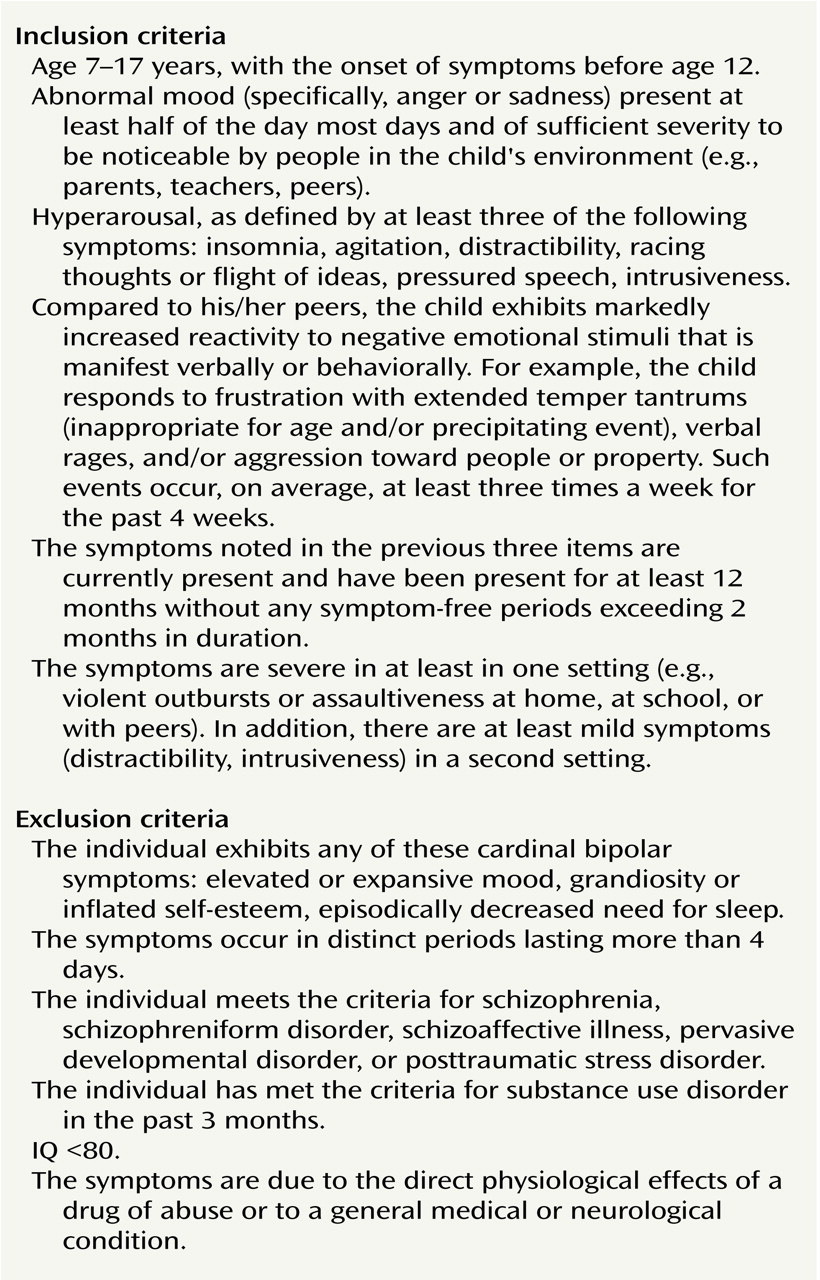

Broad Phenotype: Severe Mood and Behavioral Dysregulation

In developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for the broad phenotype (

Figure 4), we had two major goals: 1) to encompass the clinical description of the patients’ symptoms, which is reasonably consistent although not formally operationalized in the literature

(1,

34), and 2) to exclude children who fit the criteria for the narrower (hypo)manic phenotypes. The clinical descriptions of the broad phenotype emphasize the children’s increased reactivity to negative emotional stimuli in the form of severe rages, as well as chronic hyperarousal (motor hyperactivity, distractibility, etc.). These symptoms, which are also seen in the narrower (hypo)manic phenotypes, form the core of our inclusion criteria. In addition, the criteria specify that the child exhibit abnormal mood between rages, in the form of sadness or anger, and that the symptoms are chronic and cause impairment in at least two settings. We exclude from the broad phenotype group children with the hallmark symptoms of elevated/expansive mood and grandiosity, those with distinct episodes of abnormal mood, and those who exhibit episodically decreased need for sleep. Our rationale for the latter is that, of all the symptoms of mania, decreased need for sleep is the one that has been shown to have pathophysiological significance

(35). However, it is important to distinguish the decreased need for sleep characteristic of (hypo)mania from nonspecific insomnia (only the latter is accompanied by tiredness), as well as from the stimulant-induced insomnia, initial insomnia, or chronically decreased need for sleep that may be seen in ADHD

(36).

In collaboration with J. Kaufman, Ph.D., we developed modifications to the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS-PL)

(37) to ensure that the broad phenotype can be diagnosed reliably. We will be testing these modifications both in our research setting and (in collaboration with Paramjit Joshi, M.D.) in tertiary care clinics. We expect that many subjects who meet the criteria for the broad phenotype will also meet the criteria for one or more DSM-IV diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder, ADHD, conduct disorder, and/or oppositional defiant disorder. However, the controversy about how to establish a diagnosis for these children has arisen in part because none of the DSM-IV diagnoses captures a relatively homogeneous population of patients with mood disturbance, hyperarousal, and decreased frustration tolerance. Therefore, it is reasonable to begin with a clearly operationalized description of the broad phenotype and to treat DSM-IV diagnoses as descriptive data rather than as inclusion or exclusion criteria.

While the population defined by these criteria should be more homogeneous than populations defined by DSM-IV diagnoses, it is nonetheless likely to be heterogeneous. Subgroups may be distinguishable by family history of bipolar disorder, DSM-IV diagnoses, and/or the relative severity of their mood symptoms, psychotic symptoms, hyperarousal, or behavioral dyscontrol. Longitudinal studies that examine the relationship between such variables (particularly, family history of bipolar disorder) and ultimate course are crucial. If the broad phenotype is actually a phenotype of (hypo)mania, but children with this phenotype do not meet the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for (hypo)mania because the criteria are developmentally insensitive, then one might expect the children’s symptoms to evolve as they age and to eventually approximate a more classic presentation of (hypo)mania. Alternatively, children classified as having the broad phenotype may never develop a classic (hypo)manic presentation but may nonetheless follow a clinical course in the “bipolar spectrum”

(38).

Conclusions

Research on the pathophysiology and treatment of children with mania and related syndromes would be advanced by the definition of relatively homogeneous clinical subgroupings. To test the validity of this and other phenotypic definitions, collaborative research efforts are needed so that questions about the minimum duration of an episode, the diagnostic criteria for a mixed state, and the identification of cardinal symptoms of (hypo)mania can be resolved empirically.

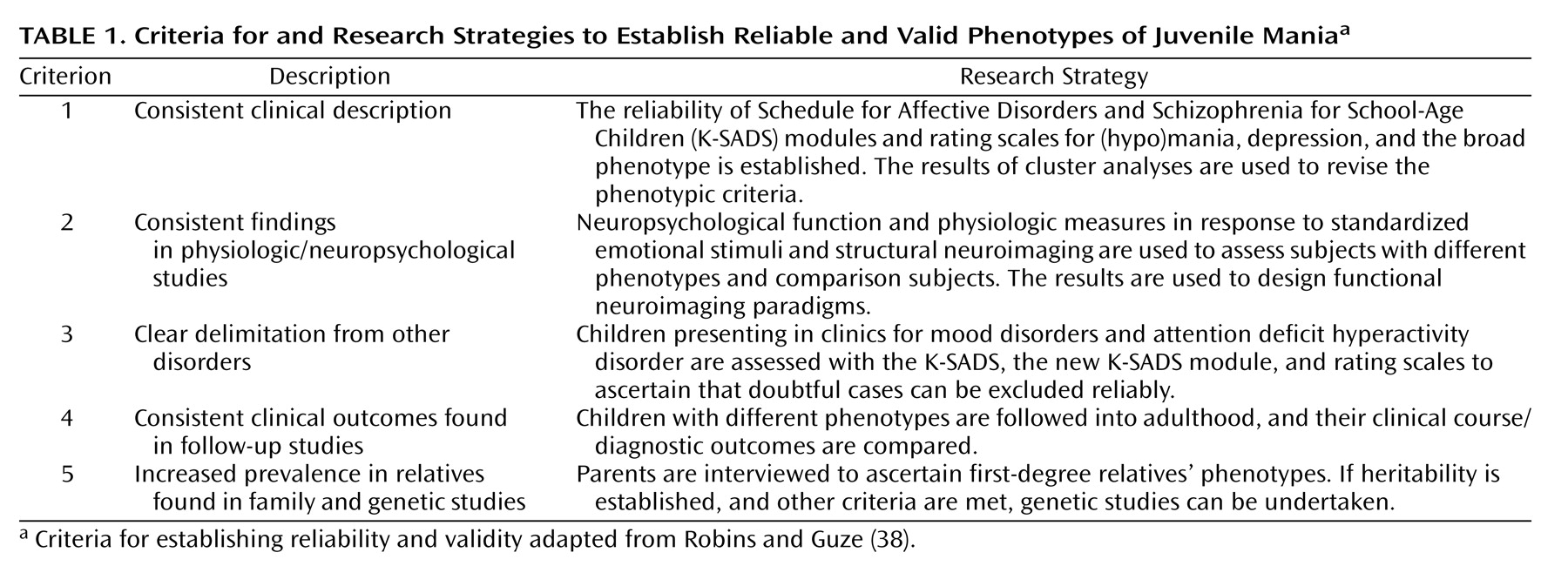

Within this phenotypic system, an important area of research concerns the extent to which the diagnostic criteria for the broad phenotype are reliable and valid. Robins and Guze

(39) suggested that a valid syndrome should meet the following criteria: 1) a consistent clinical description; 2) consistent evidence from diagnostic laboratory studies; 3) clear differentiation from other, clinically similar entities; 4) evidence from follow-up studies indicating that patients have relatively similar clinical outcomes or, at least, do not eventually fit diagnostic criteria for another entity; and 5) evidence from family studies indicating increased prevalence in relatives.

The application of these criteria to the proposed phenotypes is shown in

Table 1 (with Robins and Guze’s criteria 2 and 5

[39] updated). With regard to clinical description (Robins and Guze’s criterion 1), it is possible to test the reliability of the K-SADS-PL interview in differentiating the phenotypes and to test the ability of the broad phenotype module to identify children who meet the criteria for this phenotype (and who may or may not also meet the criteria for ADHD, major depressive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, etc.). Such a test of reliability would demonstrate that the phenotypes have clear boundaries (criterion 3). In addition, since the K-SADS-PL does not include severity ratings, it is important to develop reliable and valid rating scales for the broad phenotype as well as for (hypo)mania in children and adolescents, since the available adult (hypo)mania rating scales have not been validated in younger patients. Cluster analyses of the symptoms reported by patients and parents can be used to revise the diagnostic criteria shown in

Figure 4. Children can be followed longitudinally to ascertain clinical course, prognosis, and diagnostic stability (criterion 4). To ascertain the heritability of the phenotypes (criterion 5), parents can be interviewed about their own symptoms by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV with an additional module designed to ascertain past and present symptoms of the broad phenotype. And finally, to address Robins and Guze’s criterion 2 (the identification of physiological findings distinguishing patients with the syndrome), patients’ neuropsychological functioning, as well as their neurophysiologic response to standardized emotional stimuli, can be studied and compared across phenotypes and relative to comparison subjects. The results of these studies can then be used to design paradigms for eventual use in functional neuroimaging studies.

Clear phenotypic definitions can be used to optimize treatment, since it is helpful for clinicians to know the degree to which patients classified as having a given phenotype are likely to respond to a specific intervention. Multisite clinical trials could ascertain whether a patient’s phenotype predicts his/her clinical response to a given treatment. For example, it is conceivable that children with the narrow phenotype resemble adult patients with bipolar disorder, in which case mood stabilizers would be the medications of choice and stimulants and/or antidepressant treatments might precipitate mania or rapid cycling

(40,

41). On the other hand, very preliminary evidence indicates that children with the broad phenotype may respond well to stimulants

(42). Given the phenomenological differences between the narrow and broad phenotypes, it is possible that their optimal treatment algorithms are not identical.

The diagnosis and treatment of early-onset (hypo)mania pose considerable challenges to clinicians and researchers alike. The heterogeneity of the illness and the effect of developmental factors on its clinical presentation tax the limits of the current diagnostic nosology, leading investigators to suggest the definition of a more detailed and comprehensive phenotypic system. In suggesting one such system, along with a research program to test its reliability and validity, we hope to contribute to the field’s progress in understanding and treating this disabling illness.