Acute Porphyrias: A Case Report and Review

Case Presentation

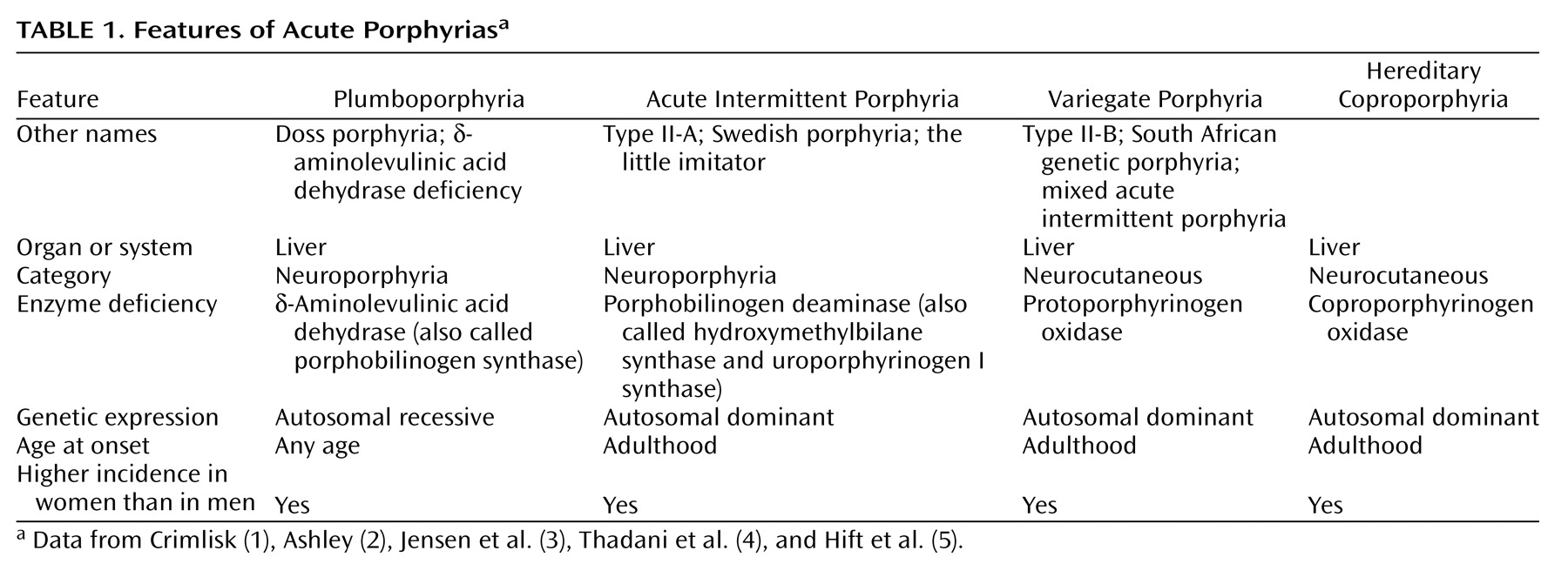

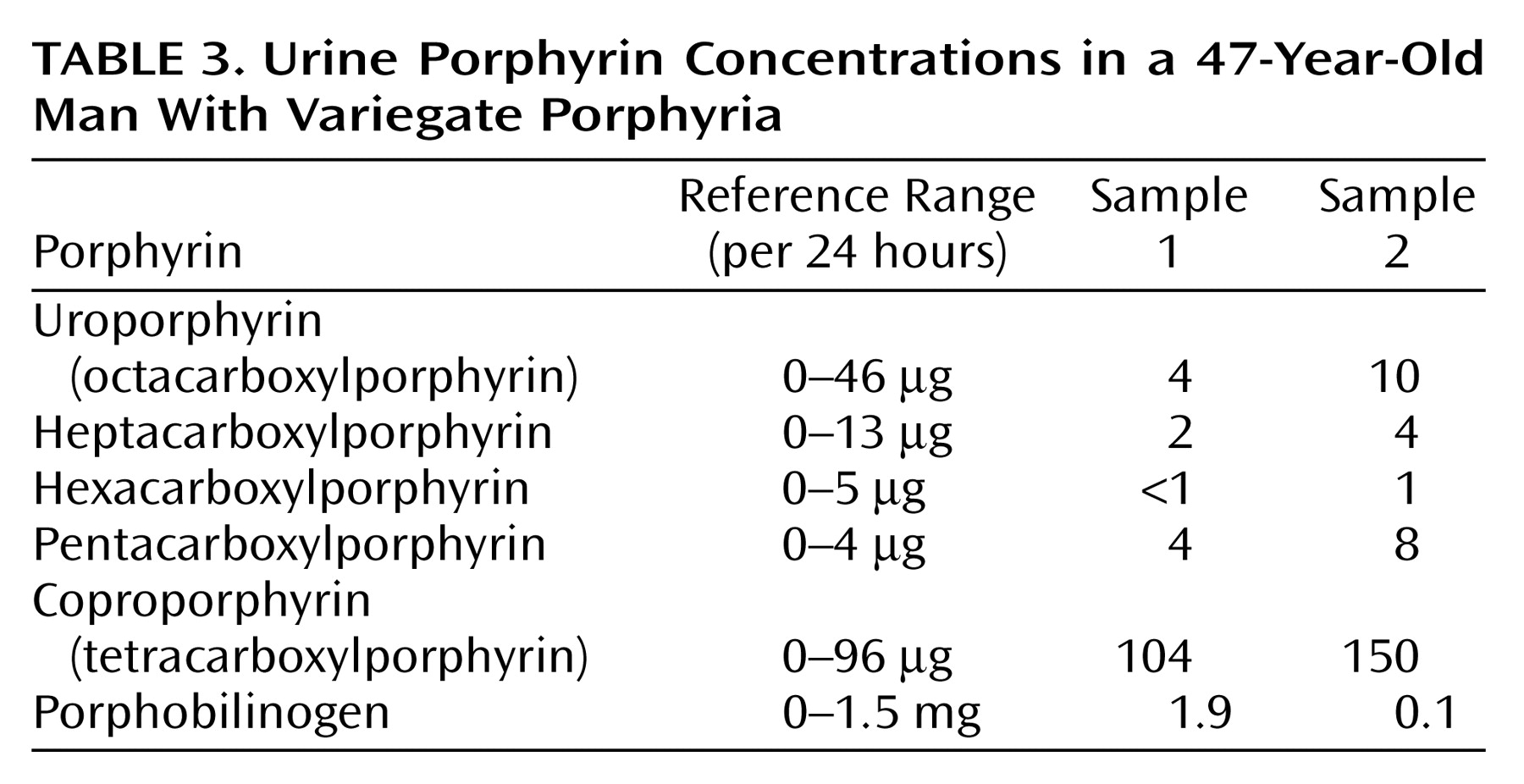

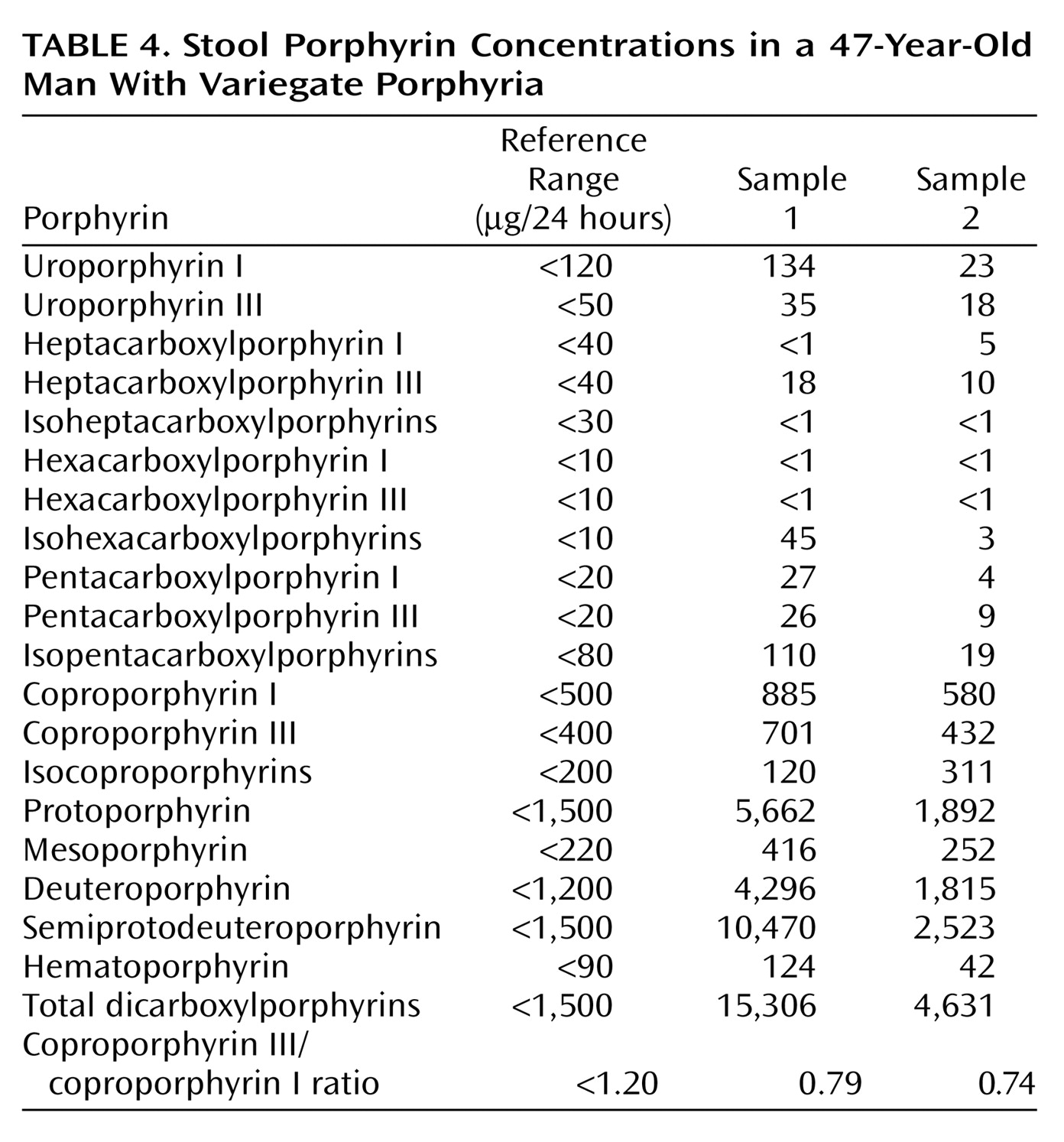

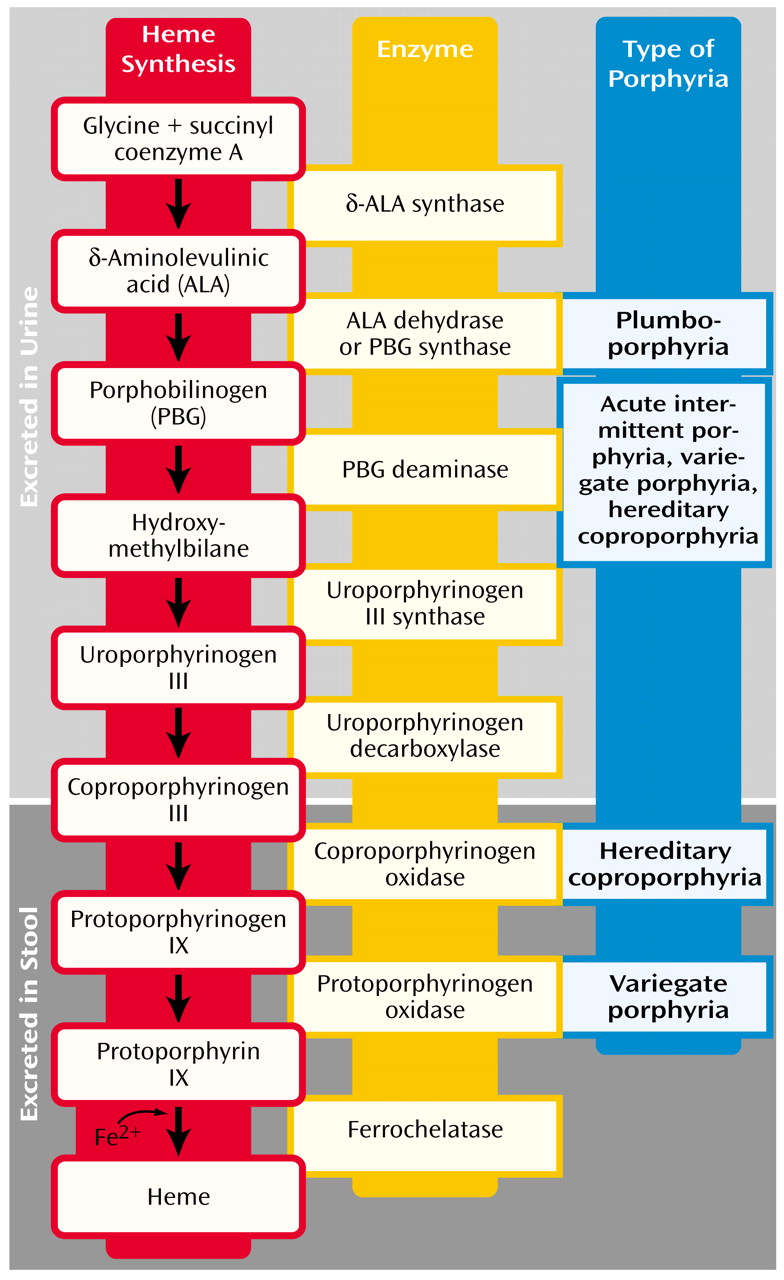

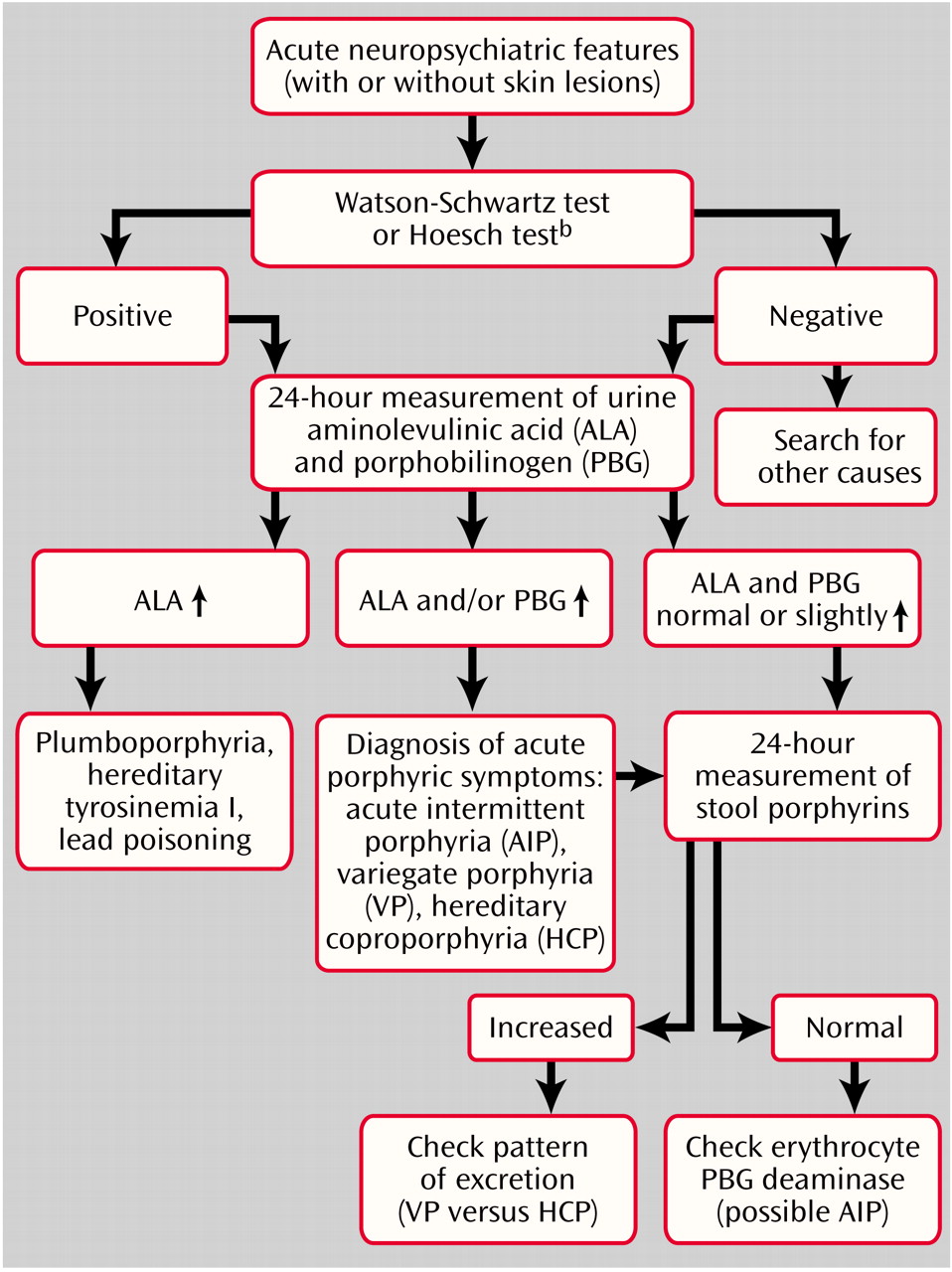

Mr. A, a 47-year-old, married, male florist with no significant previous medical or psychiatric history, presented to a local neurologist with a 3-month history of symptoms of apparent neurologic origin. He had had progressive loss of memory and concentration, spells of confusion, and indeterminate jerking spasms of the upper extremities and facial muscles that lasted only seconds but occurred up to 30 times per day. The neurologic examination was normal; the neurologist did not make a specific diagnosis but did prescribe nefazodone, an antidepressant.A few weeks later, psychiatric symptoms developed that were serious enough to warrant admission to a local hospital. Mr. A had paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations. He heard animals in his room and thought the police wanted to harm him. He had hyponatremia, so before his transfer to the psychiatric ward, an internist evaluated him but offered no specific explanation for the hyponatremia. A psychiatric mood disorder was diagnosed, and Mr. A was prescribed sertraline, valproic acid, and perphenazine and dismissed after 5 days. Four days later, he was rehospitalized, still psychotic and hyponatremic. This time the hyponatremia was attributed to psychogenic polydipsia. Venlafaxine was substituted for sertraline, and his dismissal instructions recommended gradually discontinuing valproic acid and perphenazine.Mr. A continued to display a peculiar mixture of neurologic, psychiatric, and medical symptoms. Spells of confusion and jerking spasms became longer and more frequent. Hyponatremia recurred several times, and his cognitive abilities worsened. Personality changes developed along with mood lability, intermittent suicidal ideation, and behavioral dyscontrol. At times he withdrew to his home, exhibiting anhedonia and psychomotor slowness. At other times he acted indecisive, irritable, physically agitated, and verbally aggressive. He showed disinhibited and inappropriate behavior (such as talking to strangers). He continued to have frequent ego-dystonic, increasingly complex, delusional attacks, although they lasted only minutes. He thought the police were after him for stealing from his workplace, and he declared in the absence of any evidence that he had been associating with prostitutes, both male and female, and that his wife had been trying to steal his money. The formerly isolated physical finding of hyponatremia was now accompanied by increased thirst and urination, nausea, fluctuating weight, occasional dizziness, shortness of breath, dysphagia, and decreased sexual drive and performance. Even so, his treating physicians continued to regard his entire syndrome as emanating from a functional psychiatric disorder.Five months into his illness, during an amnestic spell, Mr. A had a car accident. His family wondered whether the accident represented an attempt at suicide. Again, he was admitted to a psychiatry service, the venlafaxine regimen was changed back to sertraline, and olanzapine was added. A month later he was hospitalized again for recurrence of hyponatremia.Seven months after his initial presentation, Mr. A was referred to our institution’s outpatient neurology clinic. Although results of the neurologic examination were again normal, the neurologists thought that something was wrong. The quest for an explanation led to multiple hospitalizations on various services, including the inpatient epilepsy unit for extended video-EEG monitoring, the psychiatry unit for the Intensive Outpatient Program, and both inpatient neurology and inpatient psychiatry services. Subspecialists who offered opinions included behavioral neurologists, pulmonologists, endocrinologists, hematologists, geneticists, general internists, and psychologists. Numerous esoteric diagnoses were entertained, multiple procedures and tests ordered, and diverse medications prescribed without effect. Throughout this exhaustive evaluation, a functional psychiatric disorder continued to be considered the most likely explanation for Mr. A’s problem.Although he scored 30 of 30 on the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination, Mr. A showed marked psychomotor slowness. More formal neurocognitive testing proved challenging, hindered by his spells and slowness. A neuropsychologist was able to determine, however, that the patient’s present cognitive status was lower than expected on the basis of his education and employment and that he had unexplained low scores for confrontational naming, semantic fluency, learning and memory skills, and the Adult Verbal Learning Test.Later in Mr. A’s evaluation, an autoimmune disorder was suspected (results were positive for antinuclear antibody at 1:40 and for IgG phospholipid antibody at 1:64), but a 4-week trial of prednisone therapy that was instituted did not result in improvement. Although intriguing, nonspecific cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and an EEG tracing abnormality did not suggest a particular diagnosis. Prolonged video-EEG monitoring showed neither EEG discharge abnormalities nor changes in consciousness during multiple behavioral spells that were videotaped. A rapid progressive frontotemporal degenerative process, as well as Kuf’s disease and acute porphyria, were considered. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), electromyography (EMG), and 24-hour collection for urine and stool porphyrins were performed. Brain biopsy was contemplated but not performed. The SPECT scan showed abnormal cerebral cortical perfusion with moderate patchy reduction of flow in the temporal and postparietal lobes and more severe reduction in the superior occipital regions. EMG showed mildly slowed conduction velocities, suggestive of a mild, chronic, slowly progressive, dependent peripheral neuropathy.

For Mr. A, acute porphyria was the only diagnosis that could encompass the protean clinical picture. A hematologist and a geneticist took over the patient’s care. The patient’s ineffective psychiatric medications were discontinued. Both patient and family were given supportive therapy and counseling about measures to prevent acute attacks, including proper diet and hydration and potential precipitants of acute attacks.A specific precipitating factor was not identified for Mr. A, but we noted that his illness had emerged during a period of extreme job stress, complicated by excessive smoking and caffeine intake. We advised his not returning to work at the florist shop because of the pressure. We warned him that smoking 2 to 3 packs of cigarettes and drinking 8 to 10 cups of coffee per day could exacerbate his symptoms. We considered the possibility that chemicals used in the floral shop could be adding to his troubles, although this seemed unlikely, given his several years of working in the shop.Genetic testing was considered in order to confirm the diagnosis, but a search for a laboratory that would analyze the samples was unsuccessful. Family counseling, including genetic counseling, was provided to this patient and his two children. Because variegate porphyria is autosomal dominant, a 50% possibility exists for the genetic defect to occur in Mr. A’s offspring (6). In the absence of symptoms in the children, however, porphyrin testing was not recommended because even if the offspring had inherited the defect, the chance of overt expression was low.After dismissal from our medical center, Mr. A and his wife were bitter and angry about the emotional and financial strains of the disease. Therefore, they refused follow-up evaluation or further testing.

Discussion

General Background

Clinical Manifestations

Epidemiology

Workup and Diagnosis

Diagnostic Algorithm

Treatment and Prophylaxis

Genetics

Other Diagnostic Methods

Conclusions

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).