The frequent occurrence of anxiety syndromes in depressed patients has stimulated a debate over the past 20 years regarding the hierarchical relationship between anxiety and depressive disorders

(1–

5). In DSM-III, anxiety disorders were excluded if they occurred during a depressive episode. However, subsequent research indicated that patients with comorbid anxiety and depression exhibited more severe symptoms, impairment, and subjective distress and a more chronic course than those with “pure” disorders

(6–

9). These findings suggested that it was more appropriate to make a separate diagnosis of an anxiety disorder for patients with a diagnosis of depression, and the hierarchy was eliminated in DSM-III-R. That is, the hierarchical relationship was eliminated for all anxiety disorders except for generalized anxiety disorder. The validity of the continued hierarchical relationship between generalized anxiety disorder and mood disorders is the subject of the present report.

Generalized anxiety disorder, which was first defined in DSM-III, is characterized by fluctuating levels of uncontrollable worry associated with fatigue, insomnia, muscle tension, poor concentration, and irritability. The DSM-IV symptom inclusion criteria for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder overlap, with four of six generalized anxiety disorder symptoms (sleep disturbance, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, and fatigue) also constituting criteria for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. It is, therefore, understandable why both diagnoses would not be made when the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder occur only during the course of the mood disorder. According to DSM-IV, depressed patients who experience the generalized anxiety disorder syndrome when they are not depressed receive both diagnoses. However, DSM-IV precludes the diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder for patients who experience generalized anxiety disorder symptoms exclusively during the course of a mood disorder. The question remains whether depressed patients who would otherwise meet the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, except for the exclusion criterion, resemble or differ from depressed patients who do not experience symptoms suggesting generalized anxiety disorder.

In the present report from the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project, we compared demographic, clinical, family history, and psychosocial characteristics among three nonoverlapping groups of patients with a principal diagnosis of major depressive disorder: 1) those with a coexisting DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder diagnosis, 2) those with a coexisting “modified generalized anxiety disorder” diagnosis (meeting all DSM-IV criteria except the exclusion criterion), and 3) those without generalized anxiety disorder.

Results

General Characteristics of Patients

Three hundred thirty-two patients presented with a chief complaint of depression and were given a principal diagnosis of nonbipolar major depressive disorder. The group included 109 (32.8%) men and 223 (67.2%) women who ranged in age from 18 to 76 years (mean=38.7, SD=11.7). More than two-fifths of the subjects were married (N=137, 41.3%); the remainder were single (N=93, 28.0%), divorced (N=58, 17.5%), separated (N=22, 6.6%), widowed (N=5, 1.5%), or living with someone as if in a marital relationship (N=17, 5.1%). About two-thirds (N=223) had a high school degree or equivalency certificate, 8.7% (N=29) had not graduated from high school, and 24.1% (N=80) had graduated from a 4-year college. The group was predominantly white (N=293, 88.3%). The mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score of the depressed patients was 50.8 (SD=9.1). More than half the patients had experienced at least one other prior episode of major depressive disorder (N=193, 58.1%), and the median duration of the current episode was 50 weeks.

One-fifth of the patients received a diagnosis of comorbid DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder (N=68), and 14% (N=48) were designated as having modified generalized anxiety disorder. There were no differences between groups on age, gender, education, or marital status.

Clinical Correlates

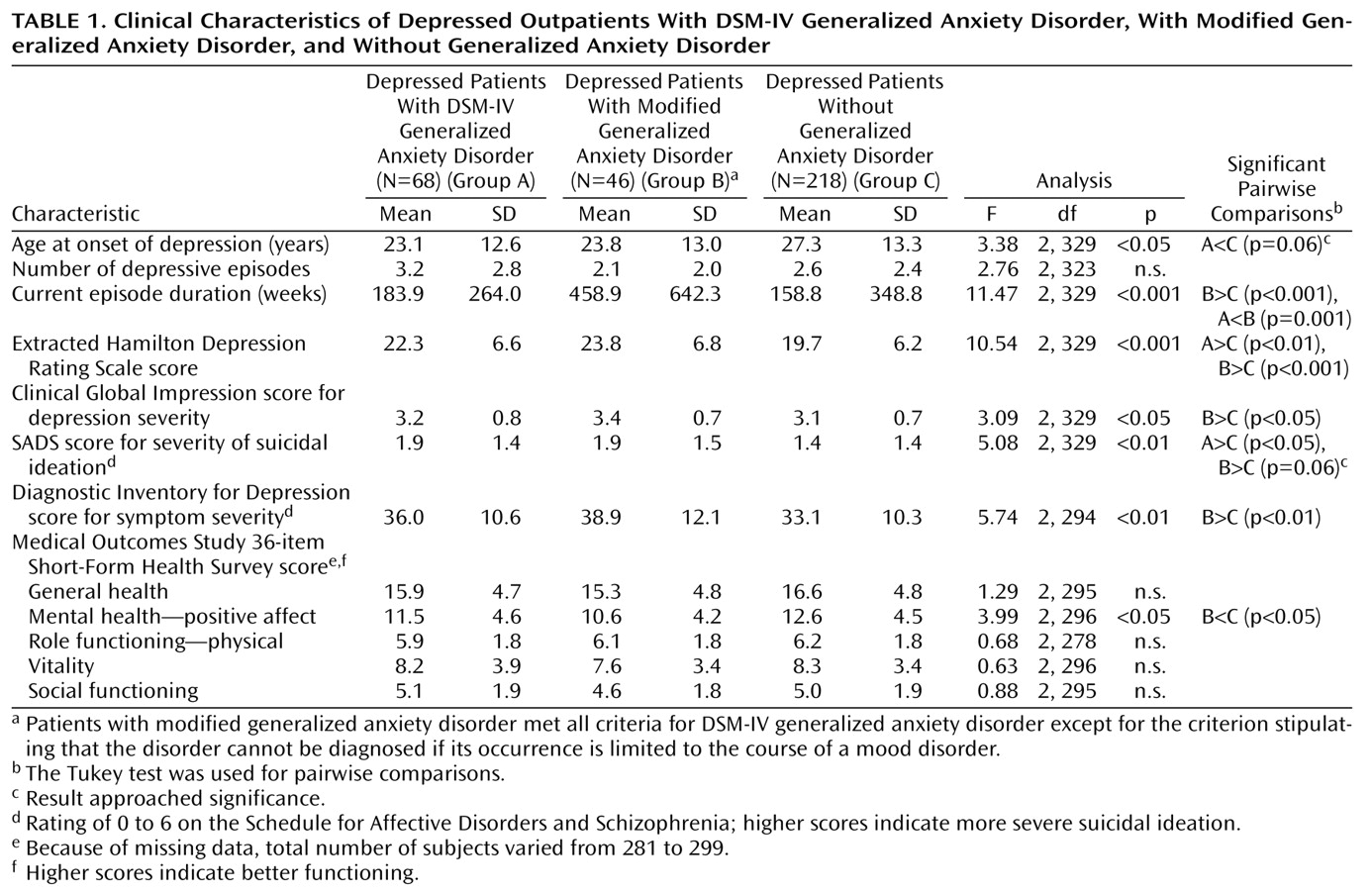

The data in

Table 1 show that the depressed patients with modified generalized anxiety disorder were more severely depressed than the group without generalized anxiety disorder on both the interview and the self-report measures of depression severity. Both anxiety disorder groups had higher levels of suicidal ideation, although the difference between the group with modified generalized anxiety disorder and the group without generalized anxiety disorder only approached significance (p=0.06). There was no difference between groups in lifetime history of suicide attempts or psychiatric hospitalization (data available upon request). The only difference between the group with DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and the group with modified generalized anxiety disorder was a longer episode duration in the modified generalized anxiety disorder group. This difference was an artifact of the method for diagnosing modified generalized anxiety disorder. The criteria for modified generalized anxiety disorder stipulated that the anxiety symptoms, of at least 6 months’ duration, must occur during the course of the mood disorder; consequently, the depressive episodes must be of at least 6 months’ duration.

A comparison of the three groups on the total number of major depressive disorder criteria met and the frequency of each of the nine individual major depressive disorder criteria found only one significant difference: compared to the patients without generalized anxiety disorder, both generalized anxiety disorder groups were significantly less likely to have experienced appetite disturbance (30.9% of the DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder group, 34.8% of the modified generalized anxiety disorder group, and 50.9% of the group without generalized anxiety disorder) (χ2=10.5, df=2, p<0.01). Likewise, a comparison of the DSM-IV and modified generalized anxiety disorder groups on the total number of generalized anxiety disorder criteria met and the frequency of the six individual generalized anxiety disorder criteria found only one significant difference: the patients with modified generalized anxiety disorder were more likely to experience concentration problems (97.8% versus 79.4% of the DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder group) (χ2=8.1, df=1, p<0.01).

More than 90% of the depressed patients with either DSM-IV or modified generalized anxiety disorder indicated that they wanted treatment to address their symptoms of chronic anxiety (91.2% and 97.8%, respectively) (χ2=2.0, df=1, n.s.)

Psychosocial Correlates

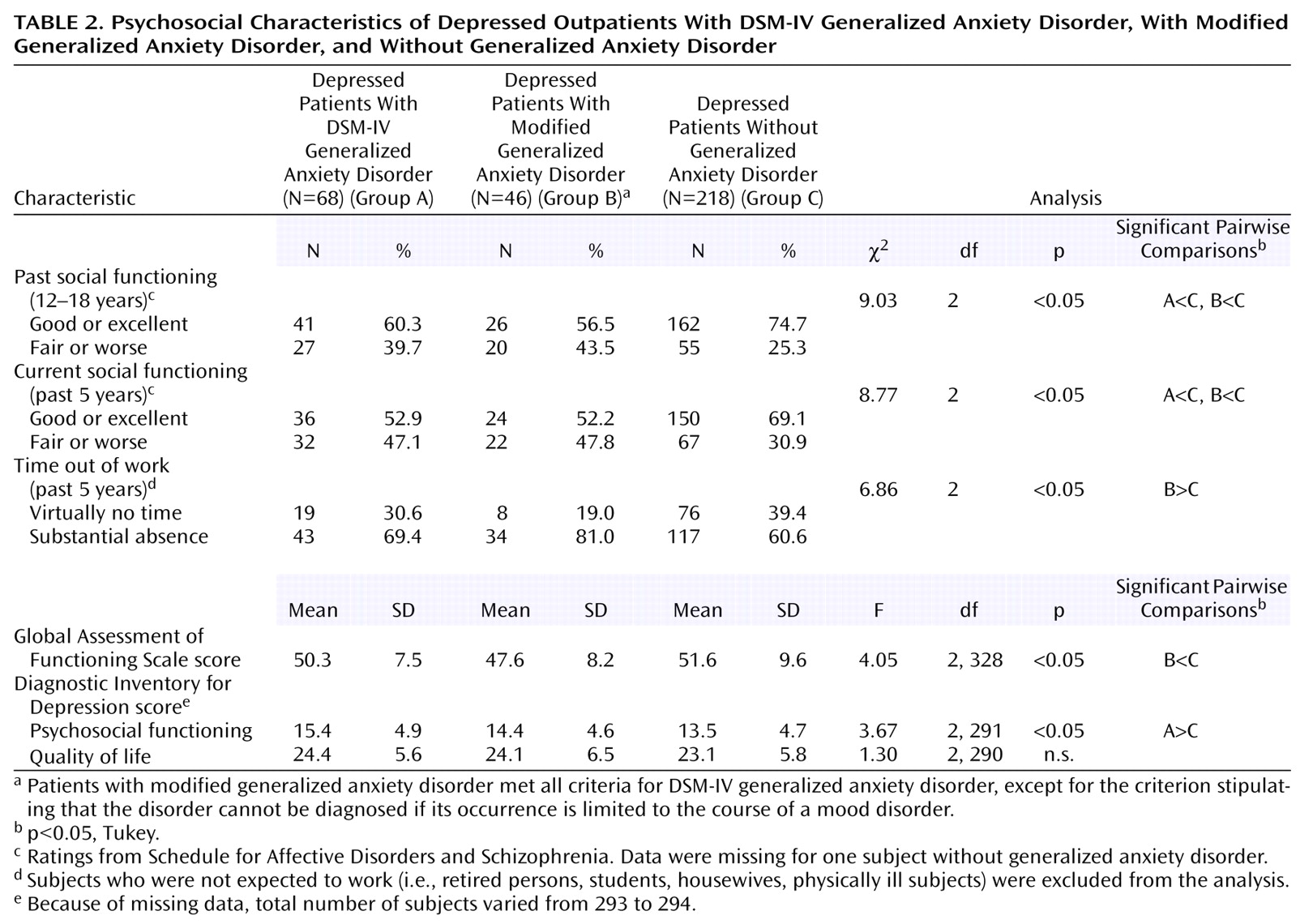

Depressed patients with DSM-IV and modified generalized anxiety disorder had poorer current and adolescent social functioning than the patients without generalized anxiety disorder (

Table 2). Compared to the patients without generalized anxiety disorder, the group with modified generalized anxiety disorder was more likely to have missed some time from work during the last 5 years, and their Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores were significantly lower. There was no difference in subjectively perceived quality of life. In the first stepwise regression analysis, which compared the groups with generalized anxiety disorder and the group without generalized anxiety disorder, current social functioning as measured with the Diagnostic Inventory for Depression was the only significant correlate (F=7.85, df=1, 289, p=0.005). In the second regression analysis, symptom severity as measured by the Hamilton depression scale and episode duration independently were associated with the distinction between modified generalized anxiety disorder and no generalized anxiety disorder (F=11.39, df=2, 218, p<0.001). Because episode duration might be confounded with the modified generalized anxiety disorder diagnosis, we repeated the regression analysis without including episode duration as one of the predictors. In this analysis, symptom severity as measured by the Hamilton depression scale and childhood social functioning were independent predictors (F=7.38, df=2, 218, p=0.001).

Penn State Worry Questionnaire scores, an index of pathological worry, were significantly different across the groups (F=18.7, df=2, 218, p<0.001). Follow-up tests indicated that the total Penn State Worry Questionnaire score was significantly higher in the depressed patients with either DSM-IV or modified generalized anxiety disorder than in those without any generalized anxiety disorder (68.1 and 65.7 versus 55.9). There was no significant difference between the two generalized anxiety disorder groups (p=0.73, Tukey).

Comorbidity as Measured by Interview and Self-Report Measures

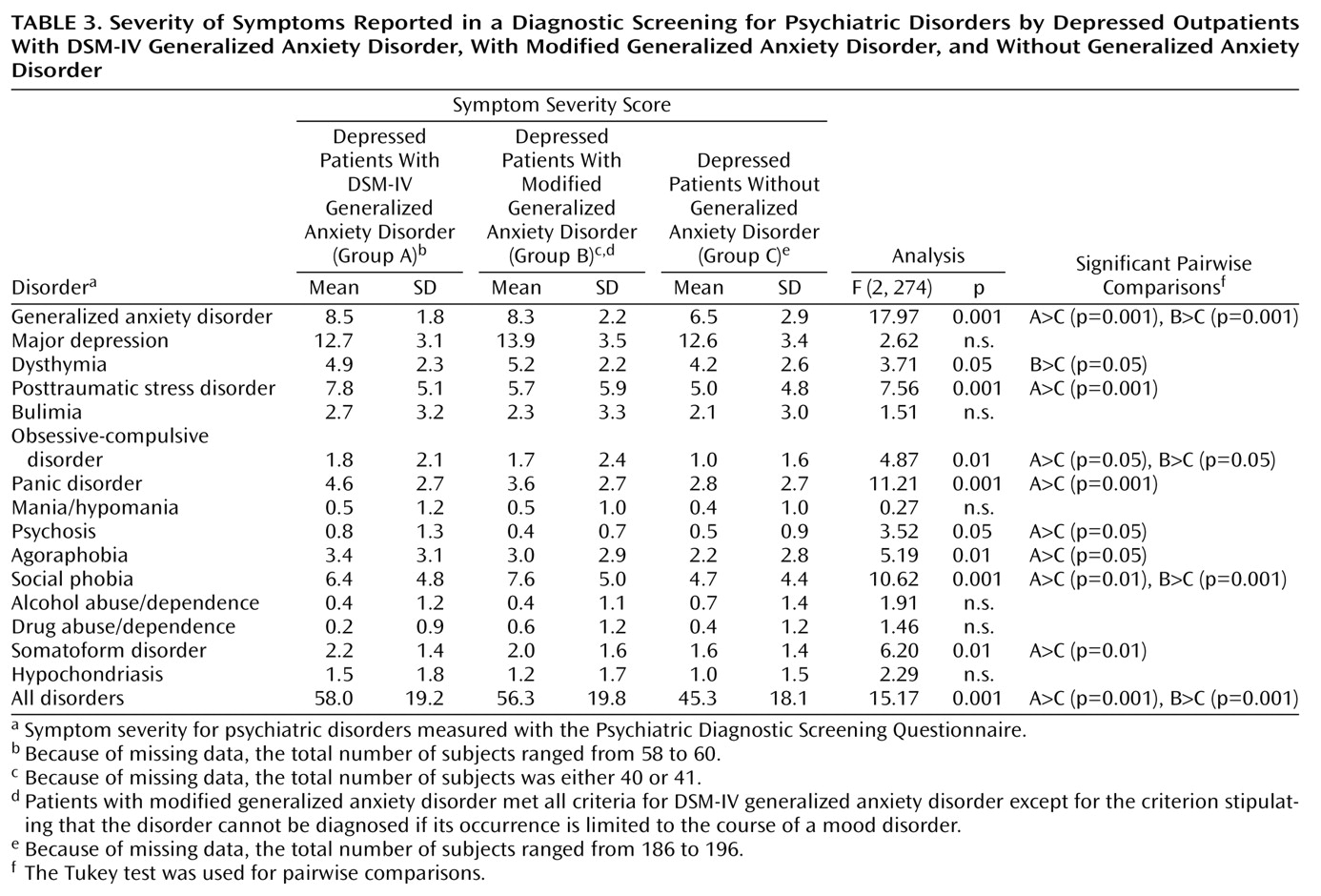

On the total Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire score, an index of the severity and breadth of axis I pathology, both generalized anxiety disorder groups scored significantly higher than the group without generalized anxiety disorder and did not score significantly different from each other (

Table 3).

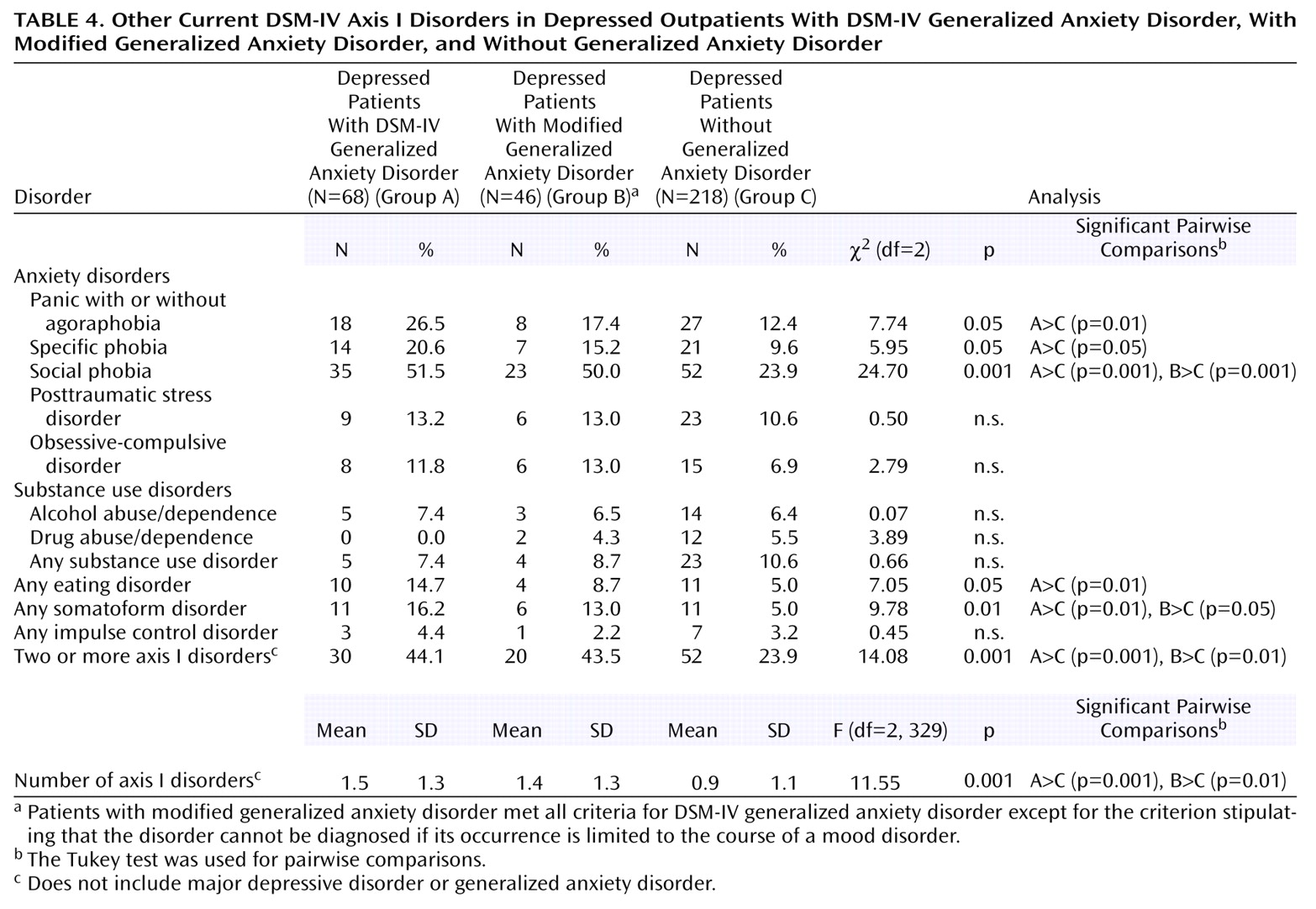

On the SCID, both groups with generalized anxiety disorder received significantly more current axis I disorder diagnoses than the patients without generalized anxiety disorder, and both generalized anxiety disorder groups were twice as likely to have two or more comorbid disorders (

Table 4). The patients with DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder had higher rates of current panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, eating disorders, and somatoform disorders than the depressed patients without generalized anxiety disorder, although only the rates for social phobia and any eating disorder were significant in the logistic regression analysis. The patients with modified generalized anxiety disorder were more likely to receive a diagnosis of social phobia and a somatoform disorder, although only the rate of social phobia remained significant in the regression analysis. There were no differences between the DSM-IV and modified generalized anxiety disorder groups.

Family History

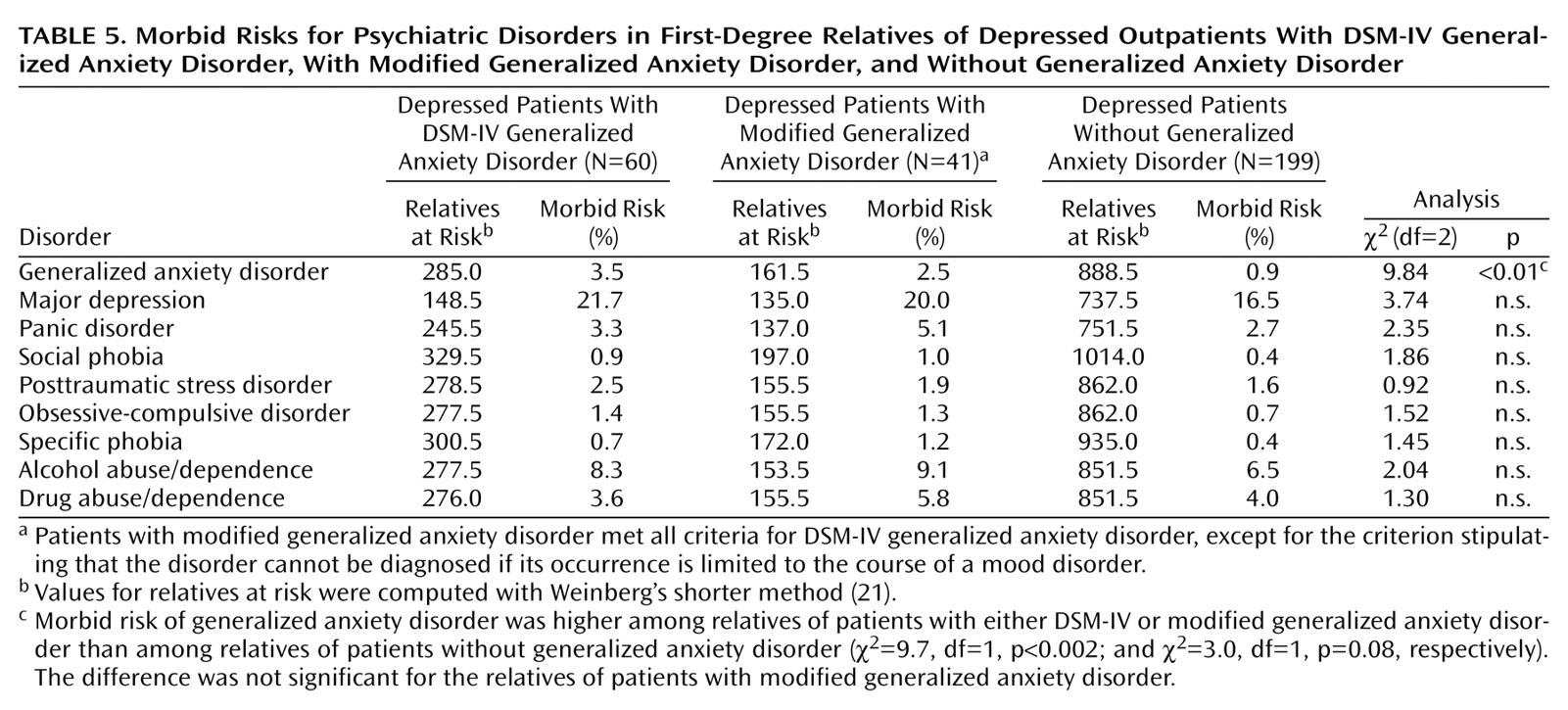

We compared the morbid risk for mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in the first-degree relatives of the three groups. Family members were considered to have a diagnosis of any of these disorders if they had received treatment for the disorder.

Table 5 shows that the only significant difference between groups was in family history of generalized anxiety disorder: the morbid risk of generalized anxiety disorder was higher in both groups of generalized anxiety disorder patients than in the group with no generalized anxiety disorder, although the difference was not significant for the group with modified generalized anxiety disorder (χ

2=3.0, df=1, p=0.08). The two generalized anxiety disorder groups did not differ from each other.

Discussion

Depressed outpatients with comorbid DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder, compared to depressed outpatients without generalized anxiety disorder, had a younger age at illness onset; a greater level of suicidal ideation; poorer social functioning; a greater frequency of other anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and somatoform disorders; higher scores on most subscales of a multidimensional self-report measure of DSM-IV axis I disorders; a greater level of pathological worry; and a higher morbid risk for generalized anxiety disorder in first-degree family members. These findings are consistent with those of other studies

(8,

9,

21,

22). The pattern of differences found in our study between the depressed patients with and without DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder was largely maintained when the group with modified generalized anxiety disorder was compared to the group without generalized anxiety disorder. Moreover, there were few differences between the patients with DSM-IV and with modified generalized anxiety disorder (except for episode duration, which was confounded with the definition of modified generalized anxiety disorder, and the frequency of impaired concentration). These findings question the validity of the DSM-IV hierarchical relationship between major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder and suggest that the modified generalized anxiety disorder group should, in fact, receive a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder.

There were more depressed patients with DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder than with modified generalized anxiety disorder (N=68 versus N=46). Although the majority of the patients who met the DSM-IV inclusion criteria for generalized anxiety disorder met the full set of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder criteria, elimination of the exclusion criterion would have markedly increased the frequency of generalized anxiety disorder in the depressed outpatients from 20.5% to 34.3%. With this change in the definition of generalized anxiety disorder, this disorder would become the most frequent comorbid anxiety disorder in depressed patients.

Depressed patients with the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder almost always wanted treatment to address these symptoms, irrespective of whether the symptoms were or were not limited to the period of depression. We reported elsewhere that there is great variability among the DSM-IV disorders in patients’ desire for treatment and that generalized anxiety disorder is one of four disorders for which most patients want treatment even when it is not the principal reason for seeking treatment

(23). One can infer patients’ relatively high level of distress and discomfort caused by their symptoms from their desire to have these symptoms addressed in treatment. From this consumer-oriented perspective, the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder are among the most bothersome of the axis I disorders.

Because our findings suggest that generalized anxiety disorder should be diagnosed whether or not the anxiety symptoms are limited to the depressive episode, we conducted a post hoc analysis to determine how the classification of the patients with modified generalized anxiety disorder affected the comparisons of depressed patients with and without generalized anxiety disorder. When the DSM-IV hierarchy was followed, and the patients with modified generalized anxiety disorder were included in the group without generalized anxiety disorder, fewer significant differences were found between the groups with and without generalized anxiety disorder than when the patients with modified generalized anxiety disorder were included with the DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder patients. Specifically, there were no longer differences between the groups with and without generalized anxiety disorder in the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score, measures of past and current social functioning, the amount of unemployment due to psychiatric symptoms, depression symptom severity as measured by the Diagnostic Inventory for Depression, the level of pathological worry, and the mental health index of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey

(17). These findings indicate that studies in which the hierarchy between depression and generalized anxiety disorder is suspended are more likely to find differences between depressed patients with and without generalized anxiety disorder than are studies that adhere to the DSM-IV hierarchy.

In the 1960s and 1970s, depressed patients were subtyped according to the presence or absence of anxiety symptoms rather than being given separate diagnoses

(24,

25). In the post-DSM-III era, the emphasis has been on making multiple diagnoses; thus, both a mood and anxiety disorder are diagnosed. Disagreement about how best to conceptualize and classify conditions with high levels of both depression and anxiety is reflected by the changes in the hierarchical exclusion rules. In DSM-III, anxiety disorders were excluded if the symptoms occurred only during the course of the mood disorder. Thus, the depression diagnosis was considered valid, whereas the anxiety symptoms were considered an epiphenomenon, or associated feature, of the depressive disorder, and an additional diagnosis was not made when the anxiety symptoms were limited to the same time period as the depressive symptoms. When the anxiety symptoms predated the onset of depression, then multiple disorders could be diagnosed. This hierarchical relationship changed in DSM-III-R, and multiple diagnoses generally were not excluded regardless of the time course of the depressive and anxious symptoms. However, evidence in support of making a separate anxiety disorder diagnosis in the depressed patients included the findings of increased rates of anxiety disorders in family members

(22).

What are the treatment and prognostic implications of the presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder in depressed patients? In general, the literature has suggested that comorbid anxiety disorder is associated with poorer outcome

(2,

26–31), although negative findings have also been reported

(32). This DSM-III-era literature is consistent with studies from the 1960s by Overall, Hollister and colleagues

(25,

33) and from the 1970s by Paykel et al.

(24,

34), which found that depressed patients with high levels of anxiety had poorer response to tricyclic antidepressants. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the question of whether the treatment of depressed patients with and without comorbid anxiety should differ, although clinical experience and inference from the extant literature suggest that the presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder affects case formulation and treatment planning. For example, pharmacologic treatment planning for depressed patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder could include referral for cognitive behavior therapy for the anxiety disorder. Choice and dosing of pharmacologic agents might also vary. If a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor is prescribed, dosage titration might be more gradual

(35). A recent study found that venlafaxine, but not fluoxetine, was superior to placebo in the treatment of depressed patients with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder

(36).

In summary, we found that depressed patients with a full generalized anxiety disorder syndrome that occurs only during the course of a depressive episode, and thus is not diagnosed according to DSM-IV, are indistinguishable in their clinical, psychosocial, family history, and demographic characteristics from depressed patients with the DSM-IV diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder. Moreover, both groups differ from depressed patients without generalized anxiety disorder. Our findings thus question the validity of the DSM-IV hierarchical relationship between major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder and suggest that the exclusion criterion should be eliminated.