Timely and appropriate treatment is vital in order to avoid depression-associated appetite and weight loss. Pregnant depressed women are more vulnerable to nicotine, drug, and alcohol abuse and failure to obtain adequate prenatal care

(15)—all factors that compromise fetal development. Maternal stress and depression during pregnancy are associated with lower birth weight and gestational age

(16), delivery by cesarean section, and admittance of infants to a neonatal care unit

(17). Neurobehavioral effects on infants of depressed mothers have been reflected in frontal lobe activity on EEGs

(18). Furthermore, maternal-fetal attachment may be explored during gestation in order to facilitate resolution of conflicts or ambivalence before delivery

(19).

Parenting Education Program

The parenting education program is a systematic didactic control condition of therapist-led weekly educational sessions. The patients were assigned a therapist and seen weekly for 45-minute sessions to discuss their symptoms and functioning. Similar to the interpersonal psychotherapy treatment, the parenting education control condition lasted for 16 weeks.

During parenting education program sessions, the therapist emphasizes the developmental stages of pregnancy, delivery, parenting, and early childhood. The therapist may also facilitate attaining concrete services (housing, etc.) but does not provide specific emotional support in any way similar to interpersonal psychotherapy.

The parenting education program permits weekly evaluation of the patient’s mood and control for contact with a professional as well as the nonspecific effects of repeated evaluations. In addition, the weekly contact with a therapist provides an ethical and reliable way of evaluating the patient’s mood. Therapists were available by beeper at all times for emergencies.

We considered using a waiting-list control; however, a waiting-list control does not control for the aforementioned variables and provides no mechanism for frequent face-to-face evaluation of worsening symptoms

(23,

24).

We report the results of a randomized controlled clinical treatment trial on the efficacy of 16 weeks of interpersonal psychotherapy compared to a parenting education control program.

Method

Training in Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Two experienced therapists (with an M.D. and a C.S.W.) received 1 year of interpersonal psychotherapy supervision. Their training included modification of their training skills to include interpersonal psychotherapy in order to provide a uniform method of procedure and psychotherapy treatment. All trainees read the interpersonal psychotherapy book and the interpersonal psychotherapy manual in preparation for the training. One Spanish-speaking therapist provided treatment for our large Latina population. The interpersonal psychotherapy training program was modeled after that used in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) collaborative study of treatment of depression

(22). A 5-day didactic program described the clinical strategies of interpersonal psychotherapy in addition to the physical, psychological, and developmental phases of pregnancy.

After the didactic sessions, the clinicians entered a clinical program that included supervision of three patients, each over a 16-week period. The patients were assigned incrementally. The therapists treated one patient at a time; a second patient was assigned when the therapist was judged to be competent in the techniques of interpersonal psychotherapy. The supervisor, who was the principal investigator (M.G.S.), made the assignments. All sessions were videotaped and subsequently reviewed by the supervisor

(30). Weekly supervision included a 1-hour videotaped review in order to ensure reliable treatment methods. After completion of all cases of interpersonal psychotherapy, certified interpersonal psychotherapists reviewed three tapes of each patient in order to determine qualification for certification.

The therapists in training met monthly to discuss patients and address problems, treatment strategies, procedural methods, and difficulties with the protocol—all to insure uniformity of method. Both therapists were judged competent. The patients treated during the therapist training were excluded from the study group.

Training in Parenting Education

The supervisor met with the therapists and provided written instruction, books on pregnancy, the postpartum, and early childhood as well as videotapes and visual aids that addressed the developmental stages of pregnancy, childbirth, and early parenting. There were few limitations on the content of instruction as long as the focus remained didactic.

The therapists tailored the parenting education program sessions to the gestational age of the study participants. Regular conferences were held to discuss and review tapes and to alert the therapists to potential treatment bias.

The important point addressed in the parenting education program was to avoid any psychological intervention that may be similar to interpersonal psychotherapy. Videotapes of both interpersonal psychotherapy and parenting education program sessions were reviewed for supervision, evaluation of the quality of sessions, treatment adherence, and integrity.

Patients

More than 200 prospective research participants were recruited to the Maternal Mental Health Program from our outpatient clinics at the New York State Psychiatric Institute of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons as well as other institutions in the New York metropolitan area. They were referred by professionals, community outreach programs, and former patients. A majority of Latina patients came from the social workers and midwives at our prenatal clinic in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Other subjects were self-referred, having heard about the Maternal Mental Health Program from newspapers, magazines, and radio announcements.

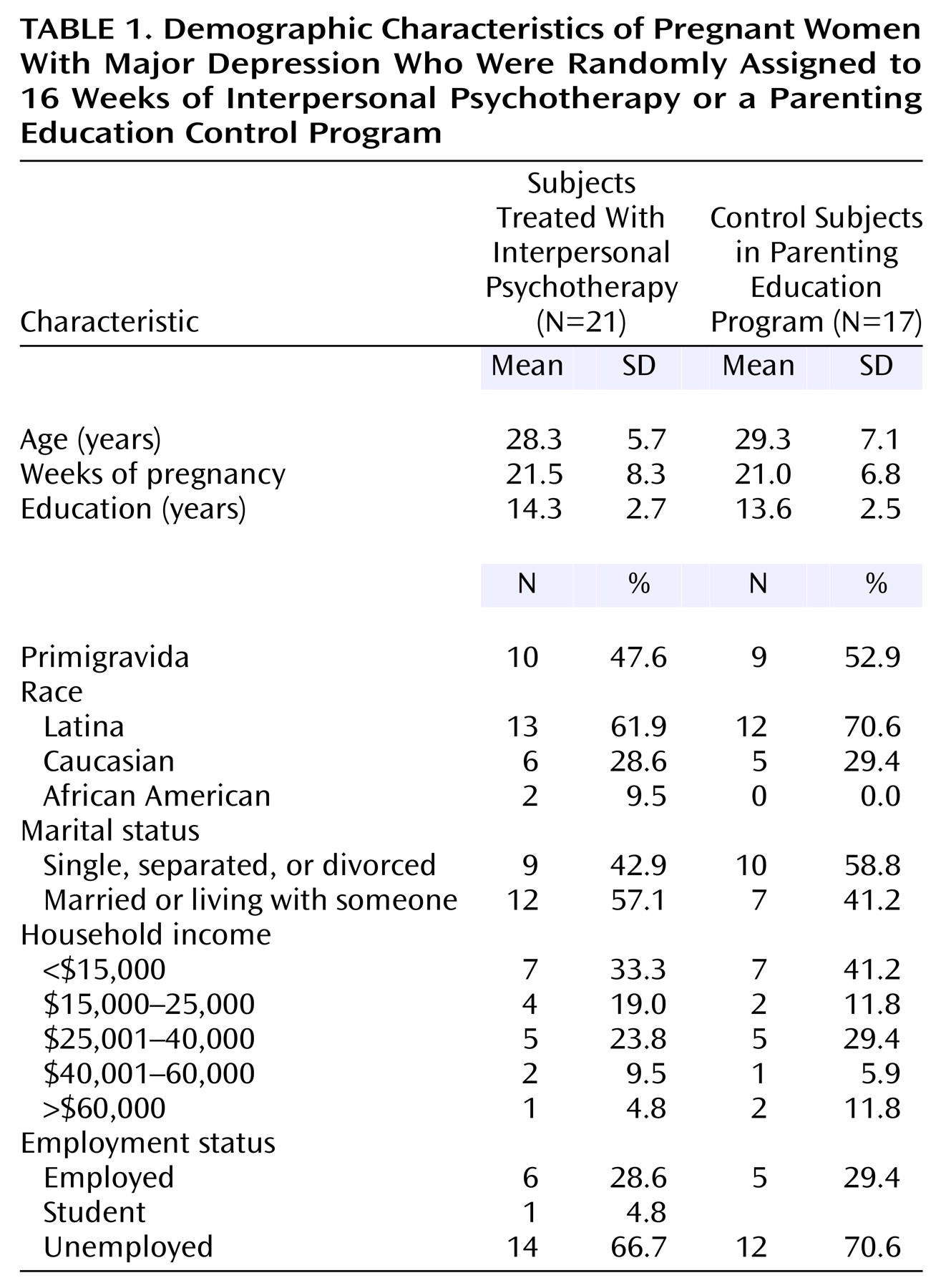

Fifty pregnant depressed women entered the study. Twenty-five were randomly assigned to the experimental treatment interpersonal psychotherapy group and 25 to the parenting education control program by using a table of random numbers. Thirty-eight women who completed at least one interpersonal psychotherapy or parenting education program session were included in the data analysis.

English- and Spanish-speaking, physically healthy pregnant women between 6 and 36 weeks’ gestation and 18 and 45 years of age were included in the study. Of the Latina women, 80% were Spanish speaking. Consent forms were bilingual. All women understood the study and gave written informed consent to participate. Diagnostic inclusion criteria were based on DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder and a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score ≥12. Only pregnant women with major depression entered the study.

Patients were excluded if they had abused drugs or alcohol in the past 6 months, were acute risks for suicide, or had comorbid axis I disorders or medical conditions likely to interfere with participation in the study. Patients currently taking antidepressant medication were also excluded from the study.

Assessments of Change

After a baseline psychiatric evaluation, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

(31) was administered to determine the presence of major depressive disorder and to rule out comorbid axis I diagnosis.

All assessments were translated and back-translated to Spanish in the Dominican dialect. The Hamilton depression scale

(32) was the principal clinician-rated outcome measure. Because the discomforts of pregnancy may mimic somatic symptoms of depression

(33), the patients were asked to evaluate whether symptoms such as appetite and weight change were likely due to pregnancy or depression.

The Beck Depression Inventory

(34) is a self-rated measure of depressive symptoms in both the general and puerperal

(35) populations. The cognitive-affective cluster of symptoms is the most sensitive to “true” depression during pregnancy

(36). Because the removal of the somatic cluster does not reduce the value of the Beck Depression Inventory, the somatic cluster was eliminated

(37,

38).

The self-rated Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

(39) emphasizes behavioral changes with no emphasis on somatic changes. Although primarily designed for postpartum mood states, it has been used as a sensitive measure in pregnancy

(40) and translated into Spanish

(41). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is the only self-report mood scale validated for use during pregnancy and the postpartum period (sensitivity=86%, specificity=78%). The Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

(42) provides measures of severity and improvement of depressive symptoms.

Weekly assessments of mood change were administered before interpersonal psychotherapy or parenting education program sessions in order to avoid treatment effects. A modified version of the Maudsley Mother Infant Interaction Scale

(43) was used to measure mother-infant interaction in the postpartum period.

Data Analysis

Intent-to-treat analysis was performed with the last score carried forward. A group size of 38 subjects was used in the analysis (17 control and 21 treatment subjects). The chi-square test was used to determine significant differences in patient demographic and other characteristics. Pretreatment and posttreatment differences in means for both groups on outcome measures of depression were assessed by using paired t tests. Overall efficacy of treatment was assessed as follows.

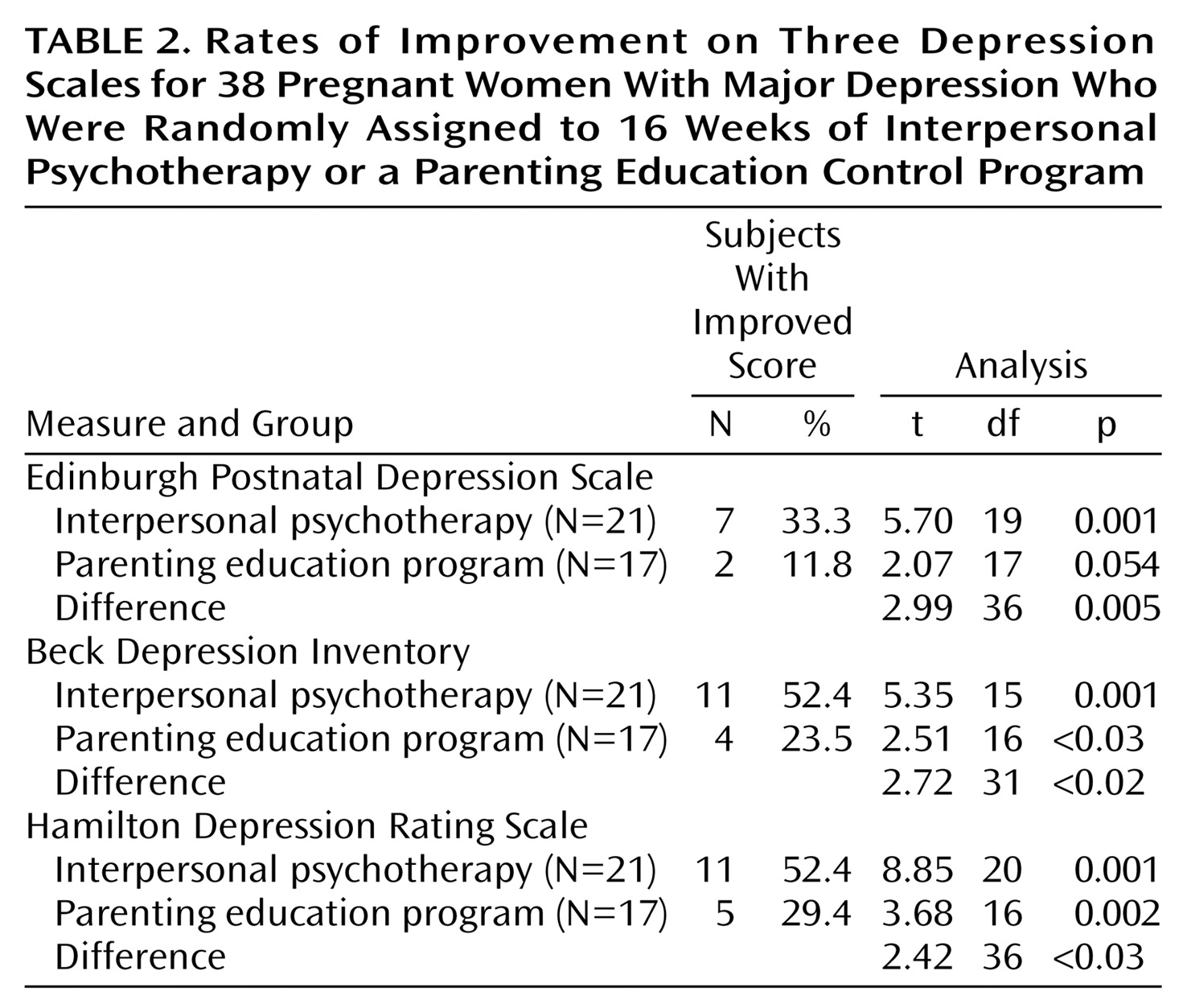

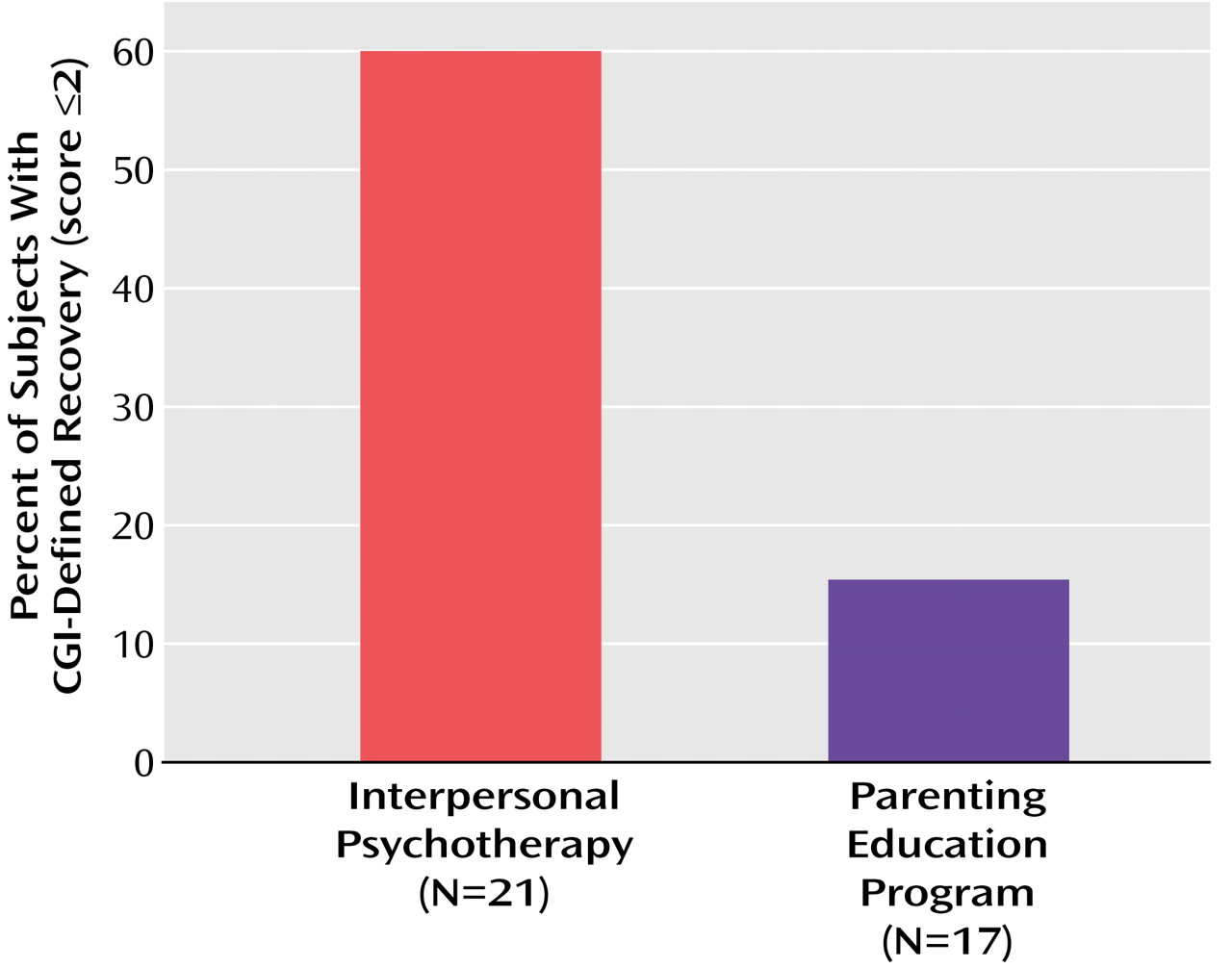

The efficacy of the two treatments was determined by comparing scores on measures of depressive symptoms (the Hamilton depression scale, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale) by using intent-to-treat analysis and the last phase as outcome, with the last score carried forward. A repeated analysis of variance model was used to compare outcome scores of the two groups at termination. Recovery status of the two groups was compared by using contingency-table chi-square tests and defined as a score of ≤6 on the Hamilton depression scale or a CGI of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to compare scores on the Maudsley Mother Infant Interaction Scale and the Hamilton depression scale. All statistical tests were two-tailed and used an alpha level of 0.05.

Discussion

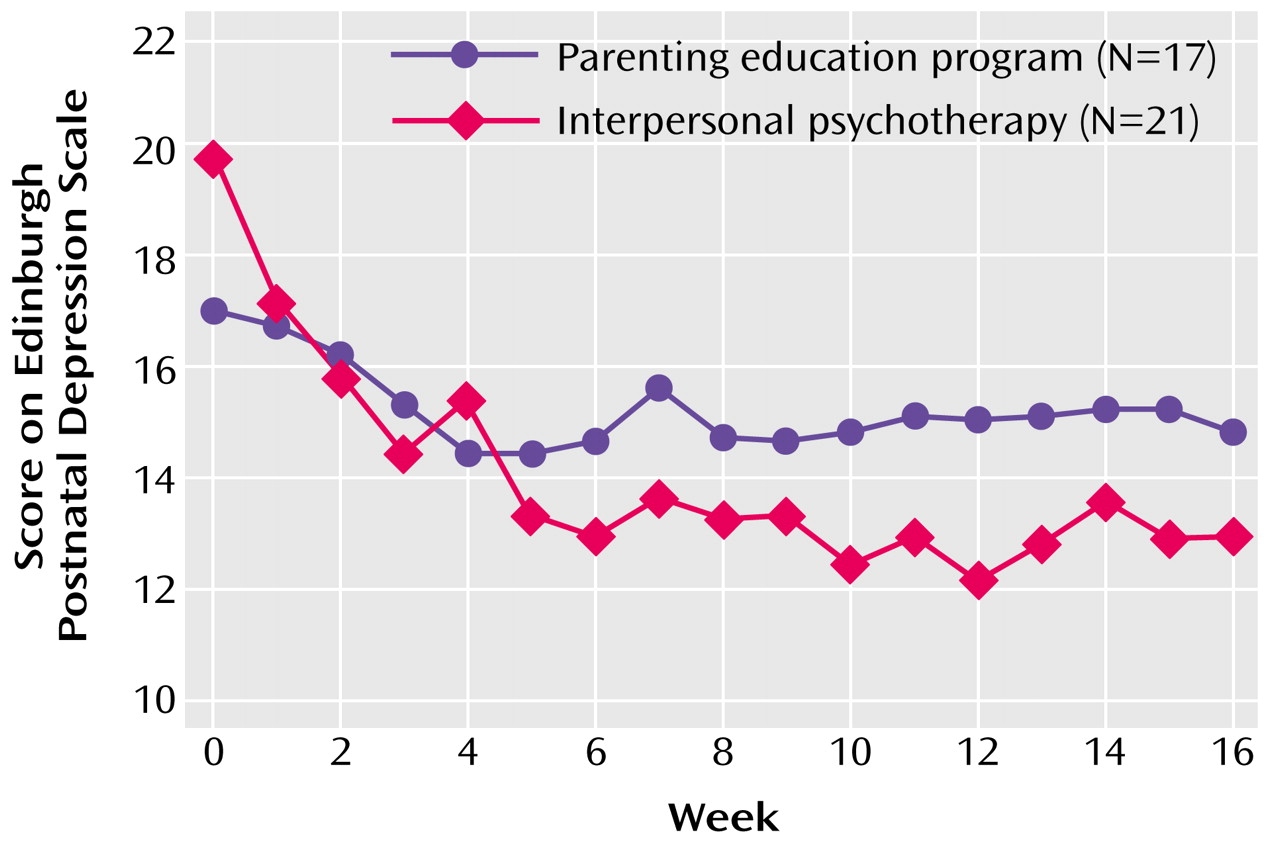

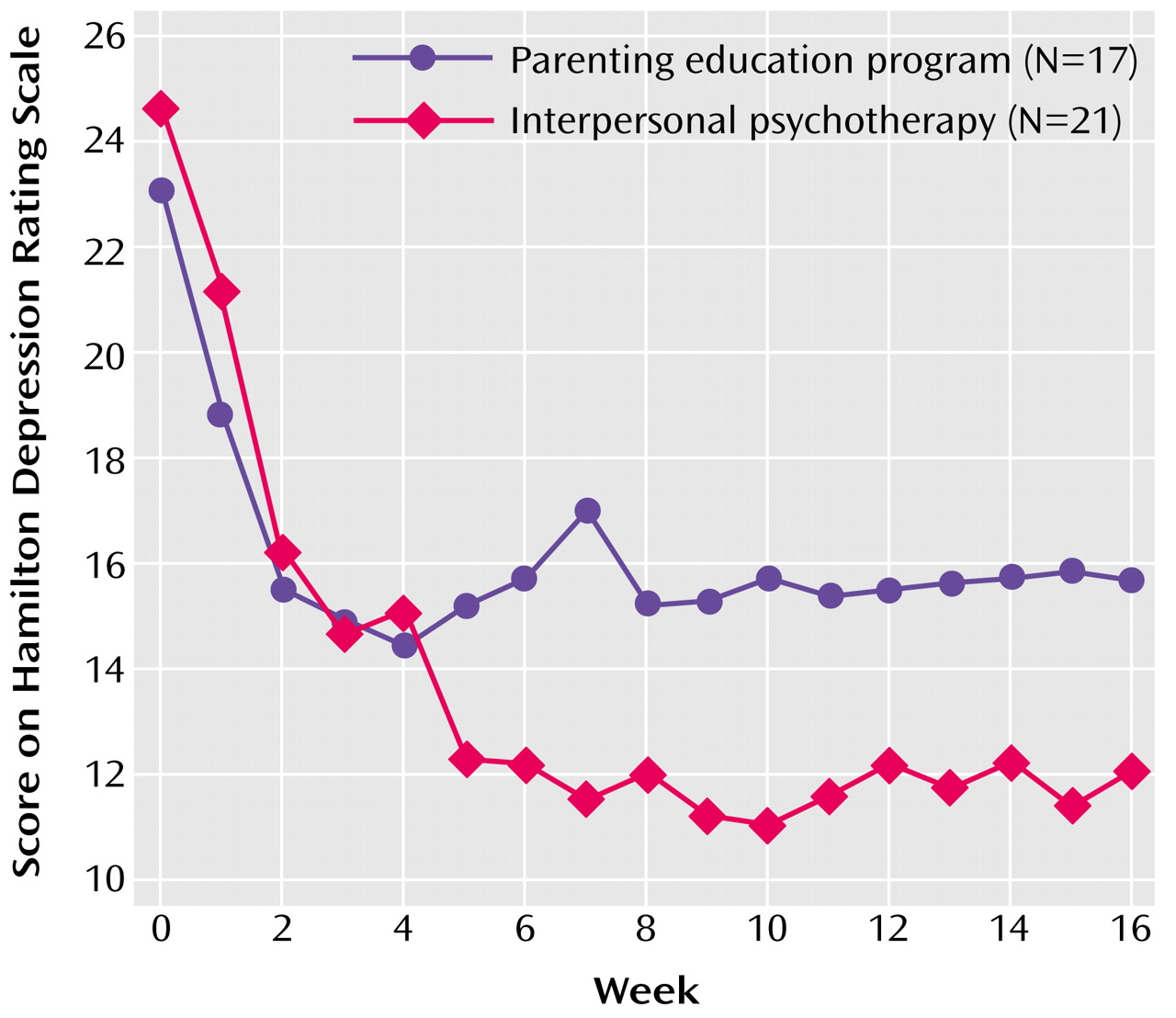

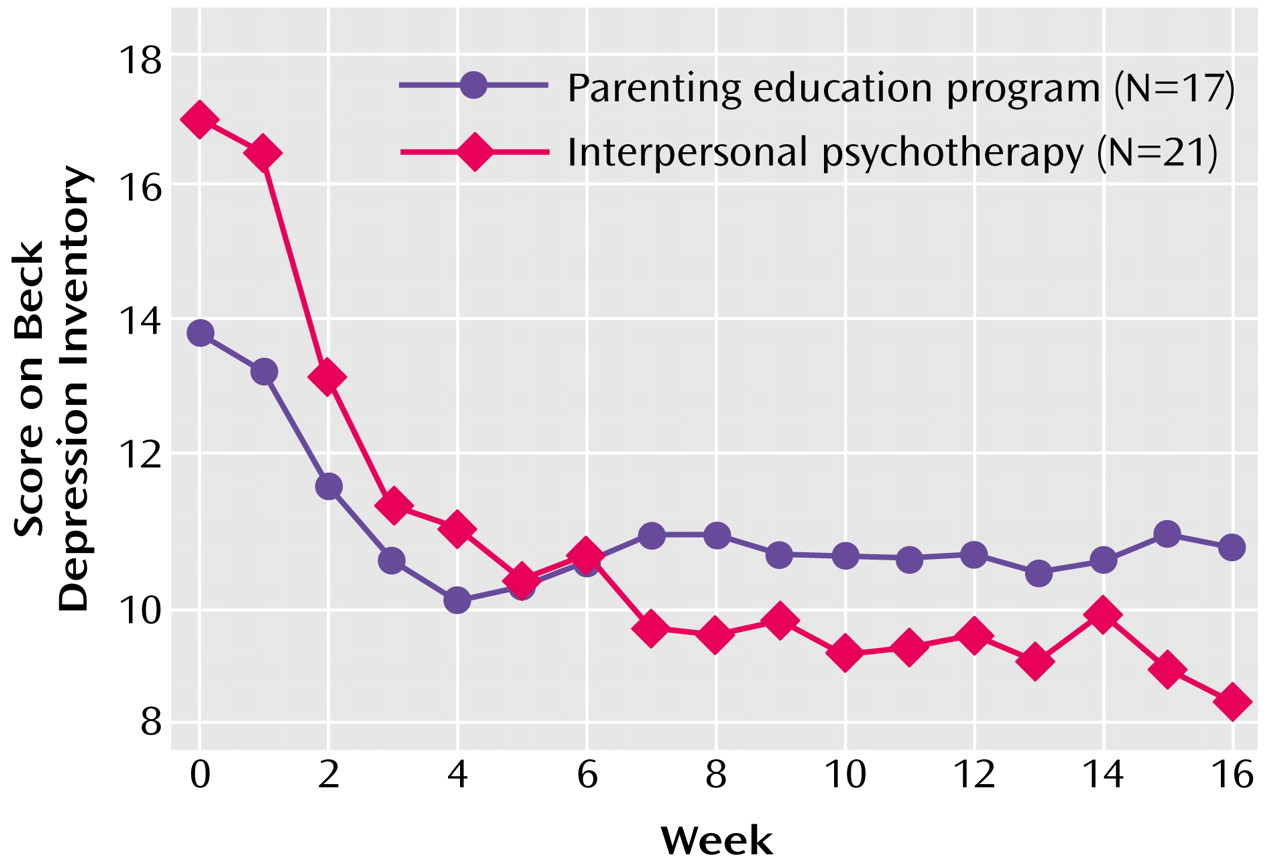

Interpersonal psychotherapy resulted in a significant mood improvement relative to the parenting education program control condition based on all mood measures: the Hamilton depression scale, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and CGI symptom recovery. Most notable was the significant difference in the recovery rate between the treatment and control groups on the CGI. In general, the graphic representations for all treatment measures were the same, with a steeper downward curve at week 7 and continued fluctuation through week 12 for the treatment group compared to the plateau of the control group. The similar curve of the graphs suggests similar temporal mood patterns.

All data outcomes were significant except for the Hamilton depression scale recovery scores. This is likely attributed to the weight of Hamilton depression scale somatic symptoms, which are similar to the discomforts of pregnancy. In an effort to correct this similarity, the evaluator asked the participants if they attributed a somatic symptom such as sleeplessness to pregnancy (i.e., from fetal movement) or depression

(33). The item was scored if they believed it was a consequence of their depression. In retrospect, we found that differences were not easily determined and likely kept the Hamilton depression scale scores artificially elevated. Our recovery criteria for the Hamilton depression scale was based on a score of ≤6, the recovery score used in the NIMH depression treatment trial, which is not indicative of the pregnant population. Therefore, recovery outcome scores on the Hamilton depression scale may not be a reliable reflection of mood in pregnant women.

Similarly, the Beck Depression Inventory also has a somatic symptom cluster

(34). However, the affective items did not compete with the discomforts of pregnancy or the immediate postpartum state. Factor analyses have demonstrated that the Beck Depression Inventory cognitive-affective cluster is as sensitive to depression during pregnancy as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which measures postpartum and antepartum changes

(36–

38). The removal of the somatic symptom cluster did not reduce the psychometric stability of the Beck Depression Inventory.

The significance of the CGI recovery data is the absence of somatic symptoms. In addition, the clinician-derived measure has demonstrated minimum clinician bias, compared to outcome based on patient ratings

(42).

A positive control effect on mood suggests that the control condition was therapeutic for some participants. Our Spanish-speaking therapist was uniquely sensitive to the cultural issues and language of this isolated group of young women, variables that likely contributed to a positive transference and therapeutic benefit. In addition, the control effects for our mood scales (the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: 11.8%, the Beck Depression Inventory=23.5%, and the Hamilton depression scale=29.4%) were similar to placebo responses in antidepressant medication studies (mean=29.7%, SD=8.3, range=12.5–51.8)

(44).

A central point of the study was the selection of a nontherapeutic systematized treatment control condition that enabled careful and sensitive detection of the benefits of interpersonal psychotherapy. Although interpersonal psychotherapy faired significantly better in some studies by use of a waiting-list control

(24), the specific benefit of psychotherapy remains undetermined because the condition did not permit examination or detection of the distinct efficacy of the interpersonal psychotherapy treatment itself. In contrast, the parenting education program controls for contact with a professional and duration of sessions as well as nonspecific effects of repeated evaluations, reassurance, and education (variables not controlled in the waiting-list control condition). Control for these measures and nonspecific therapeutic benefits enhanced our ability to assess the singular contribution of a focused interpersonal psychotherapy treatment and support our findings that the mood improvement in our group was attributable to the unique treatment effects of interpersonal psychotherapy.

The high attrition rate (32.0% for control subjects and 16.0% for treatment subjects) is attributed to several factors. Three women left after delivery, and one left after a stillbirth. Second, child care and work demands were obstacles to care for sole-support mothers. The unpredictable nature of pregnancy and young motherhood demanded that the staff be sensitive to the unique needs of young and prospective mothers. Such complications as bed rest and delivery complications required flexible measures such as the use of telephone sessions and mechanisms for child care.

The study was composed of a predominantly fragile group of recent immigrants from the Dominican Republic. Homes were often transient and chaotic, with unpredictable and unstable support systems. For some, circumstances were even more tragic. Partners were involved in drug sales and street crime, and many were incarcerated. Two women left the study when they were reunited with incarcerated partners. Many women were lost to treatment and follow-up because of disconnected telephone numbers.

In all the cases of women who were lost to follow-up, letters were sent with appropriate referrals. Our attrition rate suggests the need for more diligence in follow-up with mothers in less-permanent populations. An additional impediment to treatment may have been the duration of the treatment itself. Sixteen weeks required significant commitment and was a likely contributor to the attrition rate and our limited ability to collect postpartum information. Most interpersonal psychotherapy studies have successfully used treatment durations of 12 weeks

(23,

24). Furthermore, mean depression scores improved by the seventh week of interpersonal psychotherapy and fluctuated slightly through week 12, indicating that a 12-week trial is probably sufficient.

One unexpected finding was the high incidence of reported child abuse (47.0%). Women with a history of childhood trauma are more likely to experience depression and suicidal ideation during pregnancy

(9). Throughout normal pregnancy, the emotional attachment between mother and infant grows. The mother develops an elaborate internalized image of the fetus, a process conceptualized by Rubin

(45) as “binding in”; the fetus becomes part of the self. Consequently, the event of childbirth may exacerbate preexisting conflicts. Because parental and other early relationships may act as an imprint for future relationships, particularly with the infant, this data signals the need for early identification of mothers at risk. A trusting relationship with a therapist may function as a protective factor, providing a high-risk mother with new ways of viewing herself and others.

Although this study was primarily about treatment success, limited information was available for postpartum follow-up. Seven of eight women treated with interpersonal psychotherapy had no postpartum depression, while one treated patient did. Of three available subjects in the control group, two had postpartum depression, and one did not. We can make few inferences from this limited data. However, this information emphasizes the importance of postpartum follow-up and the potential for prevention.

There was a significant correlation of the mother’s improved mood with her ability to interact with the infant. Because this was illustrated at one time point in a small number of women (N=11), the results are not generalizable. However, our findings support those of other researchers

(46) and emphasize prevention. Depressed postpartum mothers are less sensitive to infant cues

(15) and are therefore less likely to soothe their infants, who tend to be withdrawn and inconsolable

(15,

47). Problems in behavior, cognition, and creativity often persist into early childhood and adulthood

(48).

Poverty such as that described in our study group is also an important antecedent to postpartum depression

(13). Halpern

(49) suggested that the presence of one or two difficult conditions, such as infant illness, poverty, and difficult personality, intensifies hostile feelings in the mother and emphasizes the vital need for psychiatric services.

A striking finding was a history of depression in 73.0% of our group

(5), data easily obtainable in antepartum clinics and obstetrician/midwife offices. Yet we frequently miss the opportunity for potential intervention and prevention in this accessible study group.

Another unique contribution of this study was the demonstrated feasibility of including a unique cross-section of an understudied population of socioeconomically deprived, poorly educated immigrant women. Although immigrant women comprised most of our group, African American, Caucasian, and Latina women of all socioeconomic backgrounds from the neighboring boroughs of Manhattan and the state of New Jersey were represented.

This study must be considered preliminary and the results considered in view of limitations such as the small group size and the large attrition rate. The benefit of treating mood disorders during pregnancy is far-reaching and extends to the nuclear family, the marital relationship, and parenting potential.

Replication of this study with a larger, more diverse study group will provide generalizability and further information about the effects of ethnicity and socioeconomic status on the causes and treatment outcome of antepartum depression. Mechanisms for diligent follow-up will be in place.

Financial compensation for transportation and child care must be provided to mothers in impoverished or unstable populations in order to facilitate opportunities for treatment and provide greater study feasibility in this underserved population.

Since specific guidelines for effective, safe treatment of antepartum depression do not exist, interpersonal psychotherapy should be a first-line treatment in the hierarchy of treatment guidelines for depressed pregnant women.