Major depressive disorder is associated with greater mortality

(1–

4) even after the effects of age, sex, and coexisting medical illness are controlled

(5,

6). Mortality rates increase with an increasing number of depressive symptoms

(7).

Unipolar psychotic depression is distinct from nonpsychotic depression

(8,

9) and is associated with severe symptoms, prolonged course, poor response rates, more residual symptoms, frequent relapses

(8–

11), and higher rates of hypercortisolemia or dexamethasone nonsuppression

(12). Given the severity of this disorder, we hypothesized that the mortality rates would be higher in subjects with psychotic depression than in those with nonpsychotic depression. We also hypothesized that hypercortisolemia might be associated with greater mortality.

Method

The Yale University Human Investigation Committee approved the research protocol. Inpatients who had participated in prior studies of psychotic depression or cortisol hypersecretion at Yale New Haven Hospital from 1977 to 1990

(8,

12–14) were selected and reviewed. All patients met RDC

(15), DSM-III, or DSM-III-R

(16) criteria for major depressive disorder. The distinction between psychotic and nonpsychotic depression was based on the presence of clear delusions or hallucinations. Patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, current substance abuse, or acute medical illness were excluded. The attending psychiatrist (J.C.N.) established the psychiatric diagnosis at the time of admission. All of the patients with psychotic depression from this group were included. A comparable number of patients with nonpsychotic depression who were given a standard dexamethasone suppression test (DST) during their hospitalization were selected. For patients with multiple hospitalizations, the first admission was chosen as the index admission.

To assess medical comorbidity, medical records of the index hospitalization were reviewed using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale

(17). A single rater blind to diagnosis (M.V.) performed the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale assessment.

All of the nonpsychotic and 42 of the 61 patients with psychotic depression had a standard DST during their hospital stay. Administration of the DST has been described previously

(13,

14). Briefly, 1 mg of dexamethasone was given at 11:00 p.m., and two cortisol samples (8:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. or 8:00 p.m.) were drawn the next day.

Death status was investigated by entering a subject’s name, date of birth, and social security number into a computerized search of national databases (U.S. Record Search); death certificates were obtained for those who had died. To standardize duration, we analyzed mortality data only up to 15 years following index hospital admission.

Between-group differences in dichotomous variables were assessed by using chi-square analyses with Yates’s correction. For continuous variables, t tests were used. Between-group differences in mortality rates were assessed by survival analytic techniques. Time to death, in years, was defined as the difference between year of death and year of index hospital admission. Observation times, also assessed in years, were terminated at either the number of years between index admission and 1999 (the final year in which death records were obtained), or 15 years, whichever was smaller. Relationships between patient variables and time to death were evaluated using chi-square tests based on Wilcoxon statistics derived from the analysis of Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The independent association of psychotic depression and mortality was assessed using a proportional hazards model that controlled for age and medical status.

Results

Sixty-one patients with psychotic depression and 59 patients with nonpsychotic depression were selected. The patients with psychotic depression were older than those with nonpsychotic depression (mean=62.8 years [SD=9.7] versus 57.6 years [SD=12.6], respectively; t=2.51, df=118, p=0.01) and, of those surviving, had been followed longer (mean=14.6 years [SD=1.0] versus 13.1 years [SD=1.1]; t=5.97, df=81, p<0.001). However, patients with nonpsychotic depression had higher Cumulative Illness Rating Scale scores (mean=4.6, [SD=2.8]) than did patients with psychotic depression (mean=3.8 [SD=2.9] t=1.64, df=118, p=0.10). The percentage of women within the group did not differ significantly between the patients with psychotic depression (59%, N=36) and those with nonpsychotic depression (64%, N=38).

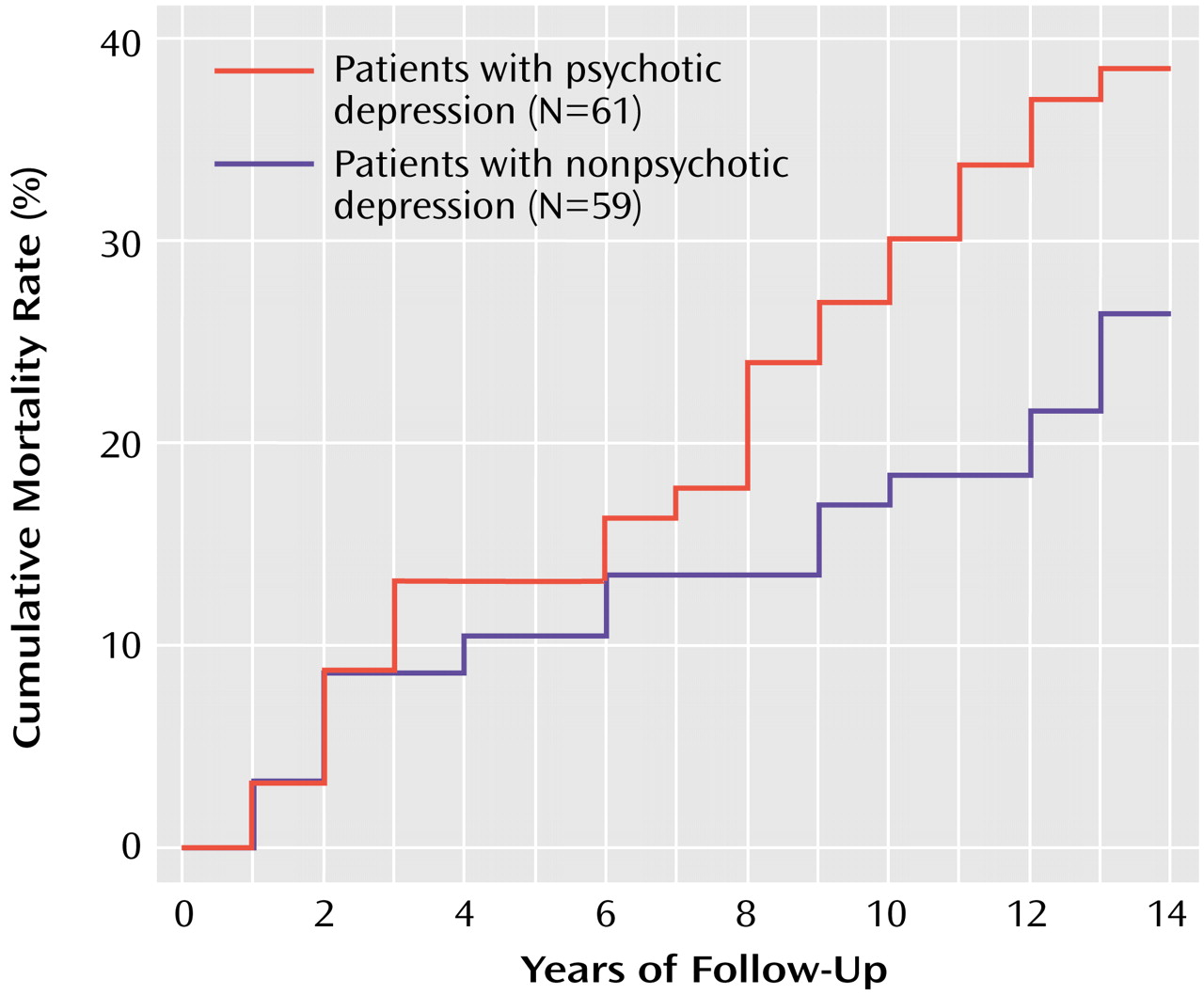

According to a survival analysis, the mortality rate in subjects with psychotic major depression was significantly greater than in those with nonpsychotic major depression (χ

2=3.99, df=1, p<0.05), with 41% (N=25) versus 20% (N=12), respectively, dying within 15 years after hospital admission. Age at entry (χ

2=9.79, df=1, p=0.002) and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score (χ

2=10.84, df=1, p=0.001) were also significantly associated with mortality rate. Sex was not significantly associated with mortality. A proportional hazards model, in which age and medical status were entered as covariates, demonstrated a significantly higher hazard for death in patients with psychotic depression than for patients with nonpsychotic depression (

Figure 1).

Patients with psychotic depression were more likely to have a positive DST (69%, N=29 of 42) than were those with nonpsychotic depression (41%, N=24 of 59) (χ2=6.82, df=1, p=0.009), and the highest mean postdexamethasone value was higher in the psychotic depression group (mean=11.9 [SD=5.8] versus 7.9 [SD=6.8]; t=3.13, df=99, p=0.002). However, DST status was not significantly associated with mortality rate in the survival analysis.

Cause of death was determined from death certificates for 34 of the 37 patients. In 30 of the patients, death resulted from medical causes. Three of the deaths were due to suicide. One motor vehicle death was suspicious for suicide. Two of the definite suicides were in the psychotic group, and one was from the nonpsychotic group. One of the 53 DST-positive patients committed suicide versus two of the 48 DST-negative patients. Group differences in suicide, either between patients with nonpsychotic versus psychotic depression or between patients with positive versus negative DST results, were not statistically significant.

Discussion

During a 15-year period following hospital admission, patients with psychotic depression were twice as likely to die as were their counterparts with nonpsychotic depression after controlling for age and medical illness. The difference in mortality rates might have been greater had subjects with psychotic depression been compared with depressed outpatients or a nondepressed sample. This finding provides further support for the distinct nature of psychotic depression.

The higher mortality among patients with psychotic depression was not explained by a higher number of suicides. Most of the deaths (30 of 34) were from medical causes. All of the suicides (including the probable case) were male patients, were violent deaths (three gunshot wounds to the head and one car crash), and occurred within 2 years of the index admission. Although it is possible that the suicide rate was underreported on the death certificates, chronic medical illness was usually present and appeared causally related.

We predicted a positive correlation between DST status and death on the basis of prior reports of cortisol’s deleterious effects on the immune system, glucose metabolism, bone, hippocampal neurons, and memory

(18–

20). A recent report

(21) confirmed an association between DST nonsuppression and suicide risk in a mixed group of patients with affective disorders. However, in our study hypercortisolemia was not related to risk of death in depressed patients.

The present study does not explain the causes behind greater mortality in psychotic depression. It is possible that patients with psychotic depression are substantially less insightful about their illness than nonpsychotic patients, and therefore less likely to follow-up with treatment. A 10-year prospective study of psychotic depression found that these patients were more symptomatic and had more psychosocial impairment

(22). This greater morbidity may be associated with greater all-cause mortality.

The findings of this study are limited by the group size and the lack of prospective monitoring of clinical status and treatment after the index admission. Nevertheless, the findings clearly show a higher mortality rate among patients with psychotic depression. The possibility that aggressive treatment might reduce mortality rates in patients with psychotic depression is intriguing and deserves further investigation.