Physicians’ specialty choices can be influenced by market forces, personality, personal experiences, preferences, and skills

(1–

7). More than any other specialty—including family medicine, in which laboratory testing and “minor” procedures play a considerable role—psychiatry focuses on interviewing, human behavior, and the doctor-patient relationship and employs a biopsychosocial, as opposed to biomedical, paradigm of health and illness

(8,

9). A recent study of 704 physicians demonstrated that compared to other specialists, psychiatrists scored higher on levels of empathy

(10). In part because the classic psychiatric disorders have no pathognomonic laboratory tests, interviewing and precise observation (the mental status examination) are the core of psychiatric diagnosis.

Although psychiatry is becoming more neuropsychiatrically oriented and third-party payers and psychiatrists’ employers require more productivity and limit time and numbers of visits with patients

(11), psychiatrists employ psychotherapy—changing behaviors through verbal interchange

(12)—much more than do other medical specialists. A 1987 national study

(11,

13) noted that psychiatrists provided five times as many psychotherapy visits as did nonpsychiatrist physicians, and a 1999 survey

(14) revealed that the average psychiatrist spent more time (39 minutes/visit) with his or her patients than did other physicians. The next highest average was for internists, who spent 20.7 minutes per visit.

Based on these perspectives, this study was designed to test the following hypotheses: psychiatrists, compared to other physicians, would

Results

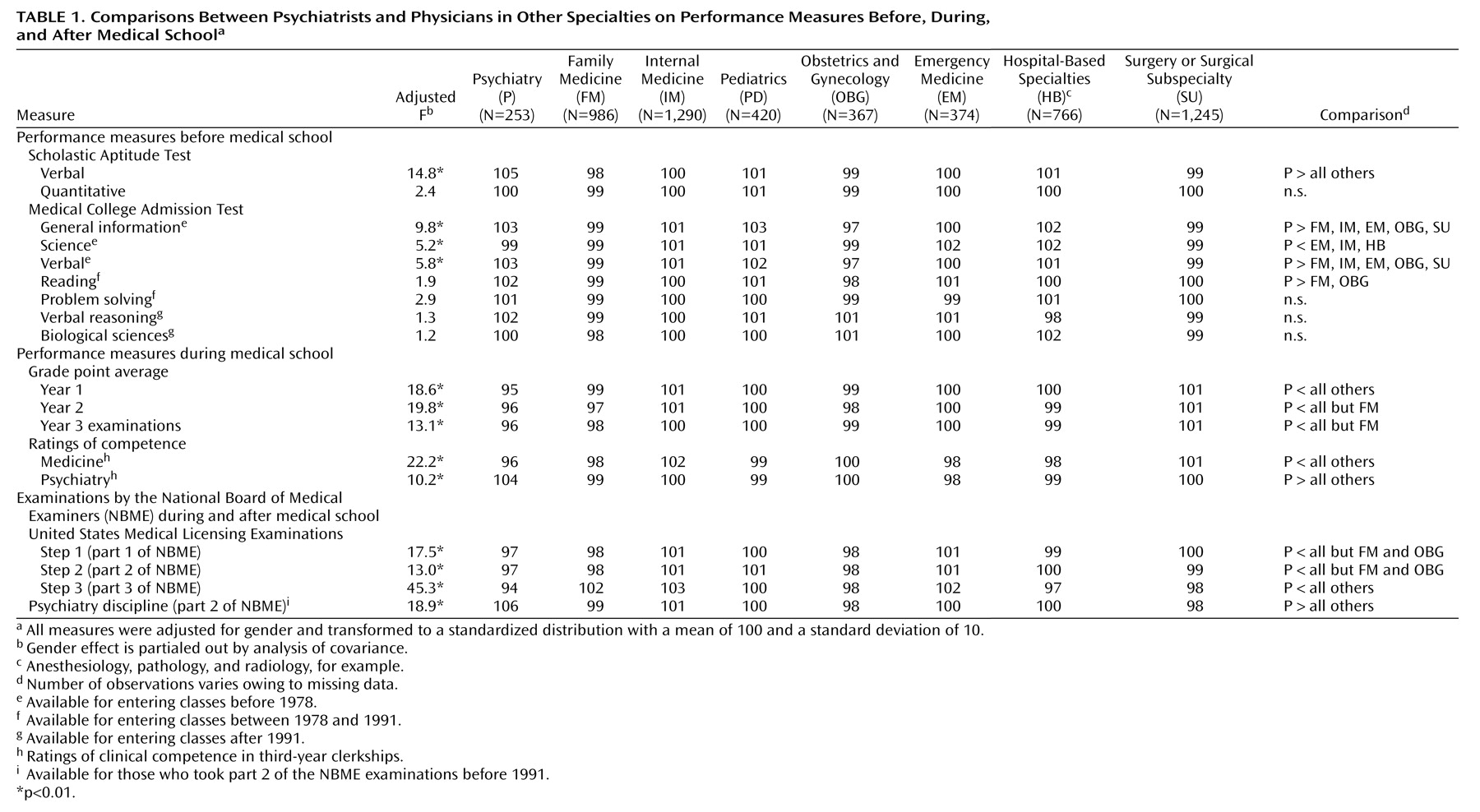

The adjusted means and the summary results of statistical analyses are reported in

Table 1. Before medical school, psychiatrists reached a significantly higher mean verbal score on the Scholastic Aptitude Test. Similarly, on the Medical College Admission Test’s verbal section, psychiatrists outscored their counterparts in family medicine, internal medicine, emergency medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and surgery. On the Medical College Admission Test reading section, psychiatrists scored significantly higher than family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. On the Medical College Admission Test’s general information section, psychiatrists outscored physicians in family, internal, and emergency medicine; obstetrics-gynecology, and surgery. No statistically significant difference was observed between the psychiatrists and others on the Scholastic Aptitude Test’s quantitative section and on the Medical College Admission Test’s problem-solving, verbal reasoning, and biological sciences sections.

During the first year of medical school, psychiatrists did not perform as well as others (

Table 1). Performance comparisons in the second year of medical school and the third-year objective examinations showed that while psychiatrists performed as well as family physicians, these two groups scored lower than their cohorts. Comparisons on global ratings of clinical competence in third-year clerkships revealed that psychiatrists obtained the highest and the lowest clinical competence ratings in psychiatry and medicine clerkships, respectively.

Regarding medical licensing examinations, in the examination of sciences basic to medicine (step 1, formerly part 1, and step 2, formerly part 2), while psychiatrists scored as well as family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists, their mean score was lower than that for other physicians. Psychiatrists outscored all other physicians on the psychiatry and behavioral science discipline of the licensing examinations (for examinees who took the NBME part 2).

On step 3 (formerly part 3), psychiatrists’ scores fell below their step 1 and 2 scores. Also on step 3, they scored lower than other physicians, including family physicians, whose scores rose dramatically from their step 2 scores, and obstetrician-gynecologists, whose scores were identical with their step 1 and 2 scores.

Similar patterns of results were obtained in additional statistical analyses in which the findings were compared for the three decades of study, indicating that the patterns of results are relatively unchanged in different time periods. Illustrative examples include psychiatrists’ Scholastic Aptitude Test verbal scores and United States Medical Licensing Examinations step 3 scores. In 1970–1979, psychiatrists and pediatricians obtained the highest mean score on the Scholastic Aptitude Test’s verbal section (mean=106, SD=10), significantly higher than internists (mean=103, SD=10), family physicians (mean=101, SD=10), obstetrician-gynecologists (mean=101, SD=9), and surgeons (mean=100, SD=11). From 1980 to 1989, psychiatrists obtained the highest mean score (mean=104, SD=10), which differed significantly from the other specialist groups (mean scores ranged from 101 [SD=10] for pediatrics to 97 [SD=10] for obstetrics-gynecology). From 1990 to 2001, psychiatrists scored the highest (mean=104, SD=9), significantly higher than physicians in any other specialty; mean scores ranged from 100 (SD=9) for pediatricians to 97 (SD=9) for family physicians.

For United States Medical Licensing Examinations step 3, we found that from 1970 to 1979, psychiatrists scored significantly lower (mean=93, SD=10) than internists (mean=105, SD=11), emergency physicians (mean=102, SD=10), family physicians (mean=101, SD=10), pediatricians (mean=99, SD=10), surgeons (mean=99, SD=9), hospital-based specialties (mean=98, SD=10), and obstetrician-gynecologists (mean=97, SD=10).

From 1980 to 1989, psychiatrists scored significantly lower (mean=95, SD=10) than internists, family physicians (mean=102, SD=10), emergency physicians (mean=101, SD=10), pediatricians (mean=100, SD=9), and obstetrician-gynecologists (mean=99, SD=10), but the differences between psychiatrists and hospital-based specialists (mean=97, SD=11) and surgeons (mean=97, SD=9) were not significant. From 1990 to 2001, psychiatrists scored significantly lower (mean=95, SD=9) than emergency physicians (mean=102, SD=8), family physicians (mean=101, SD=10), pediatricians (mean=100, SD=9), and obstetrician-gynecologists (mean=99, SD=10), but not significantly lower than surgeons (mean=97, SD=9) and hospital-based specialists (mean=96, SD=9).

Discussion

Our findings support our first hypothesis about higher performance of psychiatrists in verbal ability and essentially equal performance in science and quantitative tests before medical school. Our second hypothesis was also confirmed, as psychiatrists performed better on psychiatry and behavioral science examinations in medical school and in medical licensing examinations. Our third hypothesis about better ratings in psychiatry clerkships was also confirmed.

Our finding that psychiatrists scored lower than other physicians on step 3 of the medical licensing examination and that family physicians, internists, and emergency physicians scored best is consistent with those reported by Gonnella and colleagues

(34,

35) and Dillon and colleagues

(36). Early career specialization provides less exposure to a wide variety of clinical situations

(34,

35). Those who pursue residencies (e.g., family medicine, internal medicine, and emergency medicine) that expose them to a broad spectrum of general medical conditions during their first postgraduate year are expected to score higher on step 3, which assesses “delivering general medicine care to patients”

(37, p. 3). Psychiatrists’ low scores on United States Medical Licensing Examinations step 3, after having performed similarly to family physicians and obstetricians on steps 1 and 2, could be partially explained on this basis.

Our findings raise several questions. What do our data about psychiatrists’ and other specialists’ academic performance mean in terms of the eventual quality of care and patient health outcomes they eventually provide? Do psychiatrists’ comparatively better performances on measures of verbal skill in their psychiatry clerkships and on the psychiatry section of step 2 of the NBME translate into better mental and general health outcomes for their patients? Also, since general medical conditions are common among psychiatric patients

(38–

42), do psychiatrists’ relatively low scores on an examination in general medicine (i.e., step 3) predict poorer general or mental health outcomes for their patients?

The literature on the predictive validity of standardized written medical licensing examinations in terms of the eventual quality of patient care and patient health outcomes provides very limited information

(43,

44). Tamblyn

(43), who wrote in 1994 that “research on the predictive validity of credentialing examinations for medical practice and patient outcome is nonexistent,” recently demonstrated among 912 family physicians in Quebec

(44) the predictive validity of the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination, a written examination typically taken in the final year of medical school. The physicians who scored highest on the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination scored higher during their first 4–7 years of practice than their family physician colleagues on six clinical performance indicators (e.g., mammography screening rate, continuity of care, and disease-specific as opposed to symptom-specific prescription rates) known to be associated with clinical outcomes and costs of care. Of course, findings from a study of Canadian generalists do not necessarily generalize to American psychiatrists.

Our results strongly suggest a need for studies of the extent to which psychiatrists’ scores on licensing examinations are eventually associated with the outcomes—general medical as well as psychiatric—of their patient care. Without such validity studies, it is difficult to make definitive recommendations for curricula for third- and early fourth-year medical students planning psychiatric careers or for postgraduate first-year psychiatry residents over and above the recommendations

(45) and guidelines

(46) that already exist. It would also be valuable for the National Board of Medical Examiners to ascertain failure rates of the United States Medical Licensing Examinations step 3 by specialty. This, too, could facilitate curriculum planning.

Based on our findings, it seems reasonable to recommend that in providing career counseling to medical students planning psychiatric careers and career counseling and program planning for first-year residents that faculty advisors and program directors should be familiar with each of their trainees’ knowledge (including United States Medical Licensing Examinations data, when possible) and skills in general medicine. This familiarity should guide the planning of rotations, coursework, and study programs related to the general medical care of psychiatric patients.

A limitation of this study is that the results are from one school only and, hence, cannot automatically be generalized to all schools nationally. Nevertheless, the past 30-year track record of the study shows a consistent record of replication by the Jefferson research team and by researchers from other medical schools

(47,

48).

In summary, our findings generally confirmed our expectations about psychiatrists’ performances before, during, and after medical school. More attention should be paid to the general medical education of psychiatrists.