Pathological gambling is an impulse-control disorder not otherwise specified (DSM-IV) that is characterized by persistent and recurrent maladaptive patterns of gambling behavior. It has a prevalence of 1.6% in U.S. adults

(1) and a chronic and progressive course and is associated with an up to 20% rate of suicide attempts

(2). Comorbidity is common, particularly with substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and mood disorders. Associated bipolar disorder leads to urges, pleasure-seeking, and reduced judgment related to an unrealistic appraisal of one’s own abilities.

McElroy et al.

(3) suggested that pathological gambling (impulsivity) and bipolar disorder may be related. Not only do the clinical features of pathological gambling resemble bipolar disorder, but within bipolar disorder, pathological gambling comorbidity has been estimated at approximately 30%

(3). Similarly, 38% of inpatients hospitalized for pathological gambling have been diagnosed with hypomania

(4), and among outpatients, 24% met criteria for bipolar disorder

(5). In addition, the concept of bipolar disorder has been broadened to include bipolar spectrum disorders

(6), reflecting interest in identifying subclinical and/or subthreshold expressions of bipolar disorder

(7). Specific instruments for the diagnostic assessment of the bipolar spectrum have been developed

(7–

9).

On the basis of a phenomenological link among pathological gambling and OCD

(10) and findings of serotonin dysfunction in pathological gambling

(11,

12), several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been studied and demonstrated to be effective in at least a subgroup of pathological gambling subjects

(13–

16). However, some studies have reported a nonsignificant long-term response to SSRIs in pathological gambling compared to placebo

(17), and the SSRI fluvoxamine seemed to exacerbate gambling behavior and mood symptoms in a subgroup of pathological gambling patients with comorbid cyclothymia or bipolar spectrum conditions

(13).

Studies with mood stabilizers in other impulsive disorders, including open trials with lithium carbonate

(18) and valproate

(19) in various impulse-control disorders, placebo-controlled trials with topiramate in binge eating disorder

(20), and valproate in cluster B personality disorders

(21), have reported efficacy.

To our knowledge, to date there have been no placebo-controlled treatment studies with mood stabilizers in pathological gambling. A placebo-controlled single case report with carbamazepine in pathological gambling demonstrated clinical benefit over a 30-month maintenance period

(22). There are two reports of open-label lithium treatment in pathological gambling. Moskowitz

(23) found open-label lithium treatment to be effective in treating three pathological gamblers with bipolar features. A recently published study by our group

(24) evaluated the efficacy and safety of lithium and valproate during a 14-week, single-blind, open-label trial in pathological gamblers. Both lithium and valproate treatment demonstrated significant improvement on a pathological gambling modification of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, and the two active treatments did not significantly differ. Fourteen (60.9%) of 23 patients taking lithium and 13 (68.4%) of 19 patients taking valproate responded, based on a Clinical Global Impression improvement scale score of “much” or “very much” improved.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the efficacy and tolerability of sustained-release lithium carbonate in the treatment of bipolar spectrum pathological gambling in a 10-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel trial, the first that we know of to be conducted in this population.

Method

This 10-week, double-blind, parallel trial compared sustained-release lithium to placebo. Men and women, ages 18–65, with DSM-IV diagnoses of pathological gambling and bipolar spectrum disorder (bipolar II, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or cyclothymia) but no major medical illness were recruited by advertisements in local newspapers. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained after we provided a complete description of the study.

Bipolar I subjects were excluded because of the placebo-controlled nature of the trial. None of the subjects had ever previously received treatment with mood stabilizers and thus were treatment naive to lithium. The subjects were interviewed with the Mood Disorder Questionnaire

(8), a self-report, 13 yes/no-item, paper-and-pencil screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder derived from DSM-IV criteria and clinical experience. Inclusion criterion for score on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire was 7 or greater, as suggested by Hirschfeld and colleagues

(8). For subjects who scored 7 or more, diagnoses of pathological gambling were confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and the South Oaks Gambling Screen

(25).

Patients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, current substance abuse (except nicotine), or other organic mental disorders were excluded. In addition, patients at serious suicidal risk or those who displayed significant self-injurious behavior were excluded.

Clinical ratings and medical and laboratory evaluations, including physical and neurological examinations, a CBC, liver and thyroid function tests, electrolyte levels, and an ECG, were completed at baseline. Patients with abnormal ECG, liver function, thyroid function, or hematological findings were excluded from the study, as were patients with positive urine drug screens and patients with focal neurological abnormalities. Women of childbearing potential or who were less than 2 years postmenopausal were required to use a medically acceptable method of birth control and to have a negative serum pregnancy test before study entry.

After screening, the subjects were seen at baseline (week 0) and at the end of weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10, during which clinician and self-ratings and adverse events were recorded by means of patients’ spontaneous reports of adverse events. All subjects were at least 2 weeks free of psychotropic medications (5 weeks for fluoxetine) before entering the study. At the time of enrollment, each patient was randomly entered in a parallel fashion into a 10-week trial of either oral sustained-release lithium or placebo.

The study drug (sustained-release lithium versus placebo) was administered during the first 2 weeks, according to a fixed titration schedule and the subjects’ tolerance. The dosing regimen began with one tablet (300 oral mg in the evening) for the first 4 days, two tablets (300 mg in the morning and 300 mg at 3:00 p.m.) for the next 4 days, and three tablets (300 mg in the morning and 600 mg in the evening) for the next 6 days. Patients who were unable to tolerate or comply with these minimum dosage levels of the fixed-dosage schedule were withdrawn from the study. The dose and titration of the study drug for each patient was determined by the treating clinician based on the patient’s clinical response and tolerance of the study drug. The recommended lithium blood levels were 0.6–1.2 meq/liter from week 2 to week 4. At the discretion of the study doctor, if the patients were very much improved or had troubling side effects, the dose was not increased. An unblinded person from the laboratory reported serum lithium levels of <0.6 or >1.2 meq/liter to the clinician so that the dose of the study drug could be adjusted appropriately. Lithium blood levels were measured at weeks 2, 4, 6, and 10 (endpoint). In order to preserve the study blind, sham lithium levels were reported for selected placebo patients. During the last 4 weeks of the trial, the dose was maintained at a constant level. A pill count of unused tablets was made at each visit to help assess and reinforce compliance. Patients who missed more than 3 days of medication in any given treatment week or more than 10 days of medication during the entire treatment duration were dropped from the study. No other psychoactive medications were allowed during the study.

Primary gambling efficacy measures included the pathological gambling section of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

(26) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) pathological gambling improvement scale (score of 1 or 2 equals “very much” or “much improved” on a 7-point scale)

(27). Responder criteria at the end of the trial included both pathological gambling score reduction of 35% or more compared to baseline on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and a score of 1 or 2 on the CGI pathological gambling improvement scale. At each visit, depressive symptoms were assessed with the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(28), affective instability with the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania

(29), anxiety symptoms with the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(30), and impulsivity severity with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale

(31). Gambling severity was also assessed with the pathological gambling Behavioral Self-Report Scale

(32) and the Pathological Gambling 100-mm Visual Analog Craving Scale

(33), a modification for pathological gambling of the five self-rated 100-mm visual analog scales used to evaluate the five key components of drug craving.

The primary analyses looked at the effects of treatment on Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and CGI improvement scale scores among completers using both one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (comparing the two treatment groups on their week 10 scores) and repeated-measures ANCOVA (looking at the scores for the two treatment groups across all seven treatment sessions: weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10). In each set of analyses, the baseline scores were used as the covariates (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling score and CGI severity scale). Second, the same analyses were performed among the intent-to-treat group with the last observation carried forward. For another measure of efficacy, chi-square tests were used to compare the percentage of responders between treatment conditions. T tests were used to compare the two treatment groups at each time point on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and the CGI improvement scale to understand the time required for treatment efficacy to be measurable. Other analyses were performed to help understand the influences on and correlates of efficacy. One-way ANCOVAs among completers were conducted on scores from the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania, pathological gambling Craving Scale scores, self-reports of gambling behavior, and Hamilton depression scale and Hamilton anxiety scale scores. The relationship between gambling (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale) and affective instability (Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania) was assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The relationship between lithium blood levels and change in Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling total score, thoughts/urges, and behavior score were also assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to test other categorical variables, such as dropout. Responder analyses were performed on pre and post measures of change in the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale with paired t tests. All statistical tests used a 0.05 level of significance and were two-sided.

Results

Forty adult outpatients with DSM-IV diagnoses of pathological gambling and bipolar spectrum disorder who were free of major medical illness were enrolled out of 88 subjects screened. All enrolled subjects had a Mood Disorder Questionnaire score of 7 or higher, the recommended cutoff score for a bipolar diagnosis, with a mean score of 9.5 (SD=1.6).

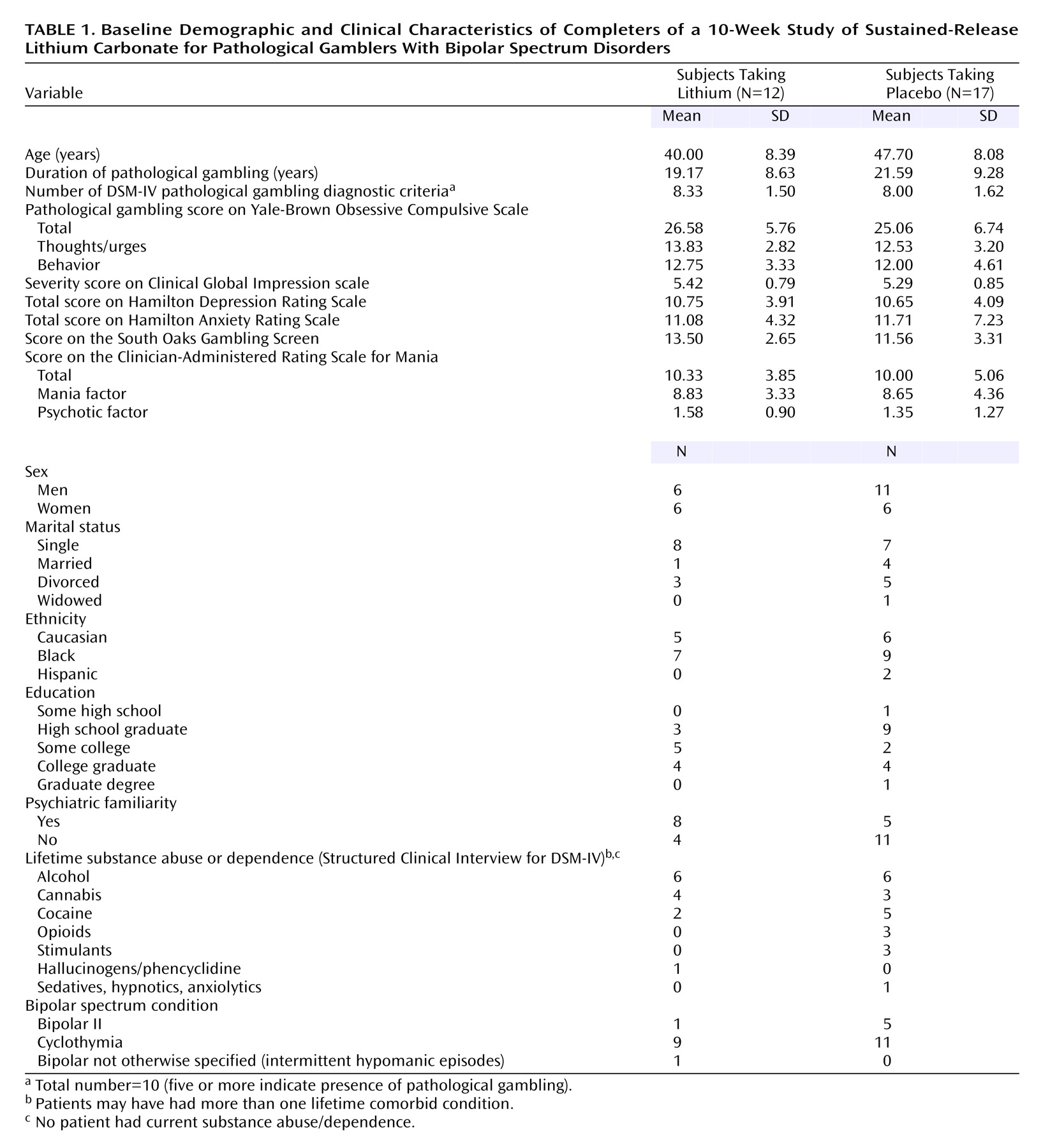

Eighteen subjects were randomly assigned to sustained-release lithium treatment and 22 to placebo. Eleven subjects dropped out of the study; these were equally likely to come from the treatment as the placebo group (six lithium/five placebo) (p=0.50, Fisher’s exact test). Dropout was unrelated to treatment efficacy, and the reasons for dropout did not differ between the groups: failure to return (five lithium/three placebo), nonadherence to the protocol (two placebo), consent retired (one lithium). Twenty-nine bipolar spectrum pathological gamblers completed the 10-week study. Baseline demographic data and the clinical characteristics of the groups are summarized in

Table 1. The mean dose at endpoint was 1150 mg (SD=215) for sustained-release lithium and 1165 mg equivalents (SD=180) for placebo. The mean lithium level at endpoint was 0.87 (SD=0.10) meq/liter.

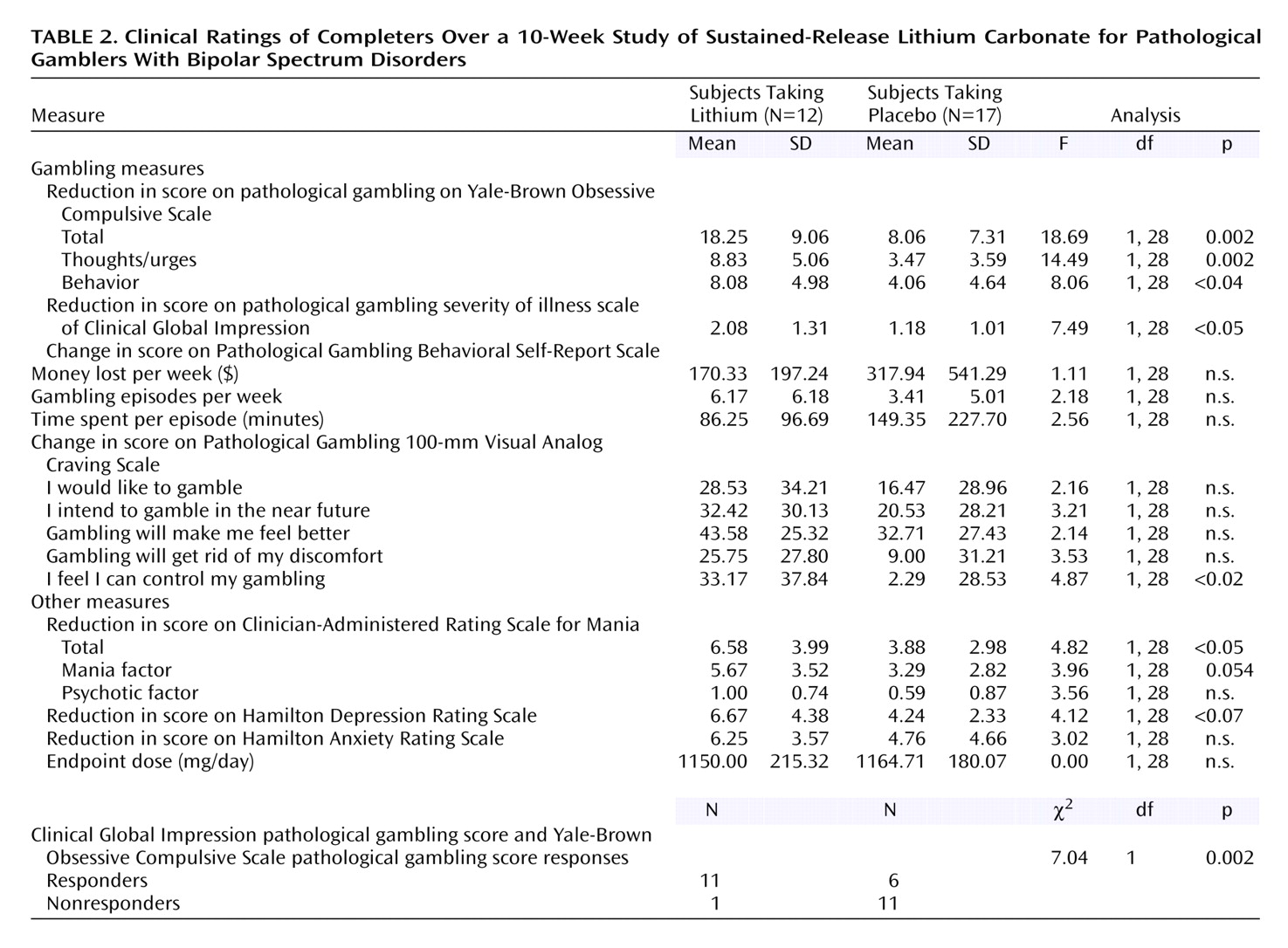

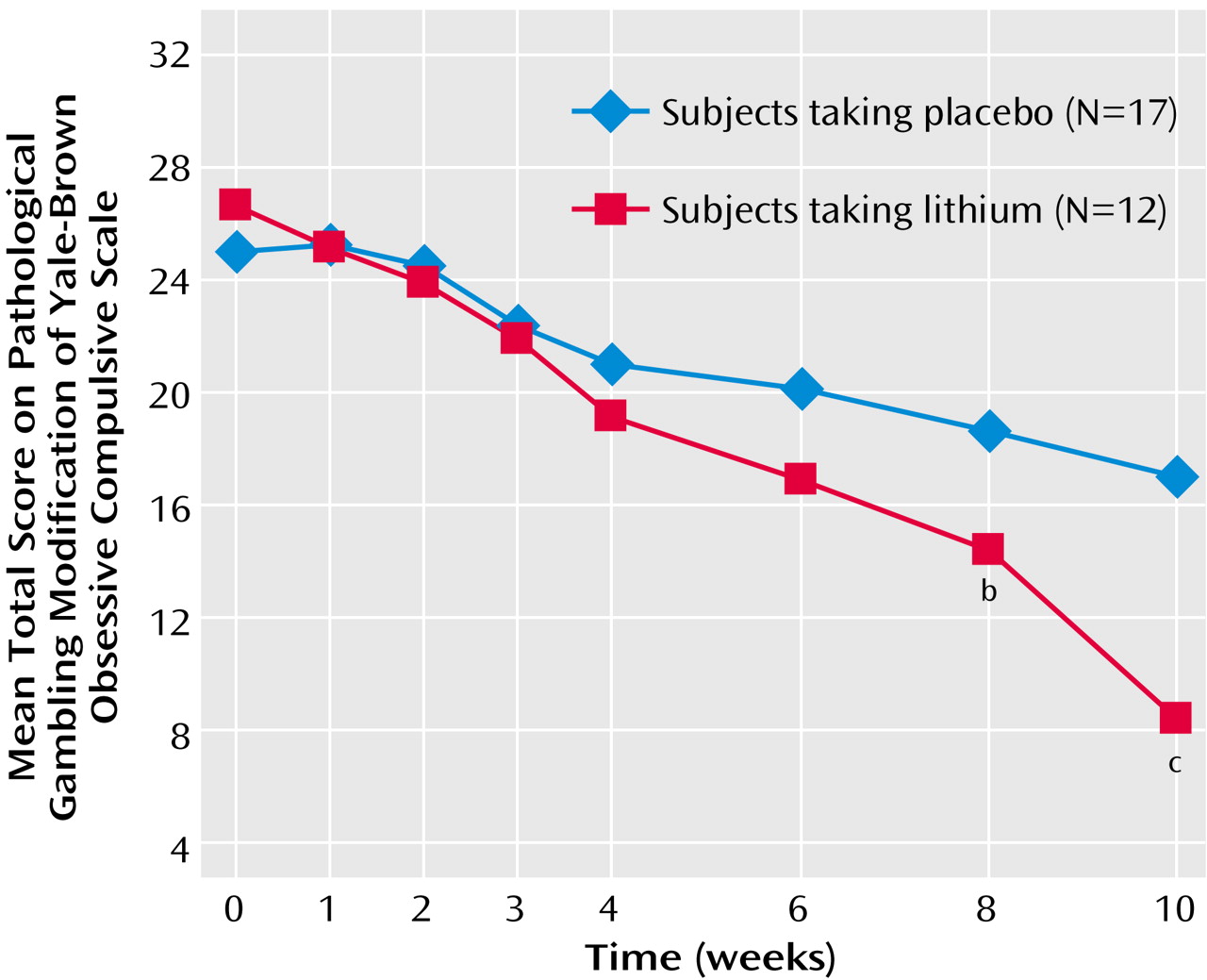

Based on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale total pathological gambling score, completers of the two treatment groups differed significantly in their gambling severity at endpoint (F=18.69, df=1, 28, p<0.001). Gambling severity was lower in the lithium group than in the placebo group at endpoint based on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale total pathological gambling score (mean=8.3, SD=5.3, versus mean=17.0, SD=5.1). This finding was confirmed by the intent-to-treat last-observation-carried-forward analysis, which also demonstrated a main effect for treatment at endpoint (F=7.03, df=1, 39, p<0.02). The two treatment groups gradually diverged and were significantly different at weeks 8 (t=2.1, df=27, p=0.04) and 10 (t=4.4, df=27, p<0.001).

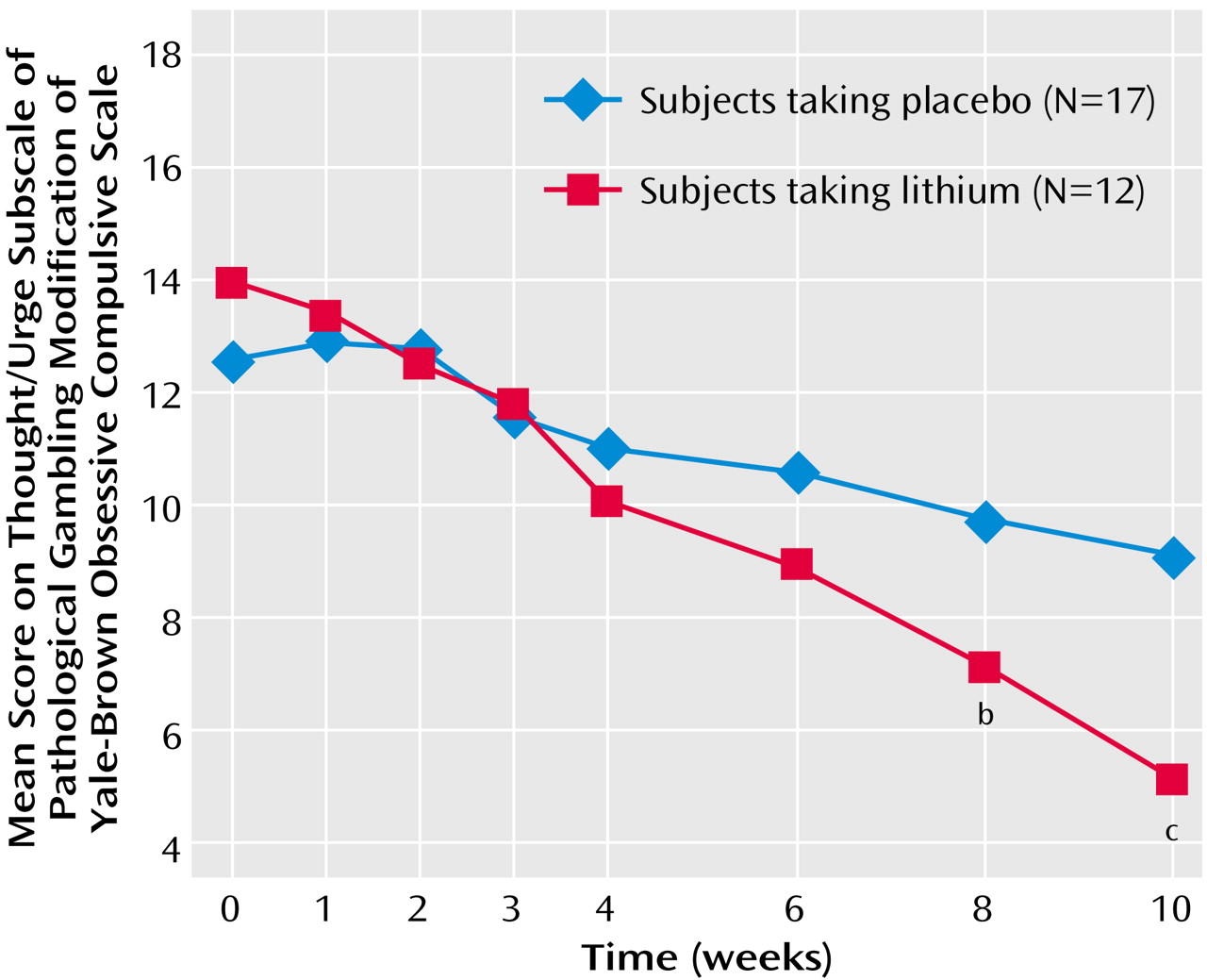

Findings were similar when the analysis of the data was done across time. Even when it included all the treatment time points (weeks 1 through 10; baseline was used as a covariate), among completers, there was a significant main effect of treatment (F=5.64, df=1, 25, p<0.03) and a significant drug-by-time interaction (F=4.18, df=6, 150, p=0.002) (

Figure 1). These basic findings were also supported by the intent-to-treat last-observation-carried-forward analysis in which the main effect of treatment was significant (F=4.57, df=1, 37, p<0.04) and the interaction between treatment and time did not quite reach significance (F=2.08, df=6, 222, p<0.10).

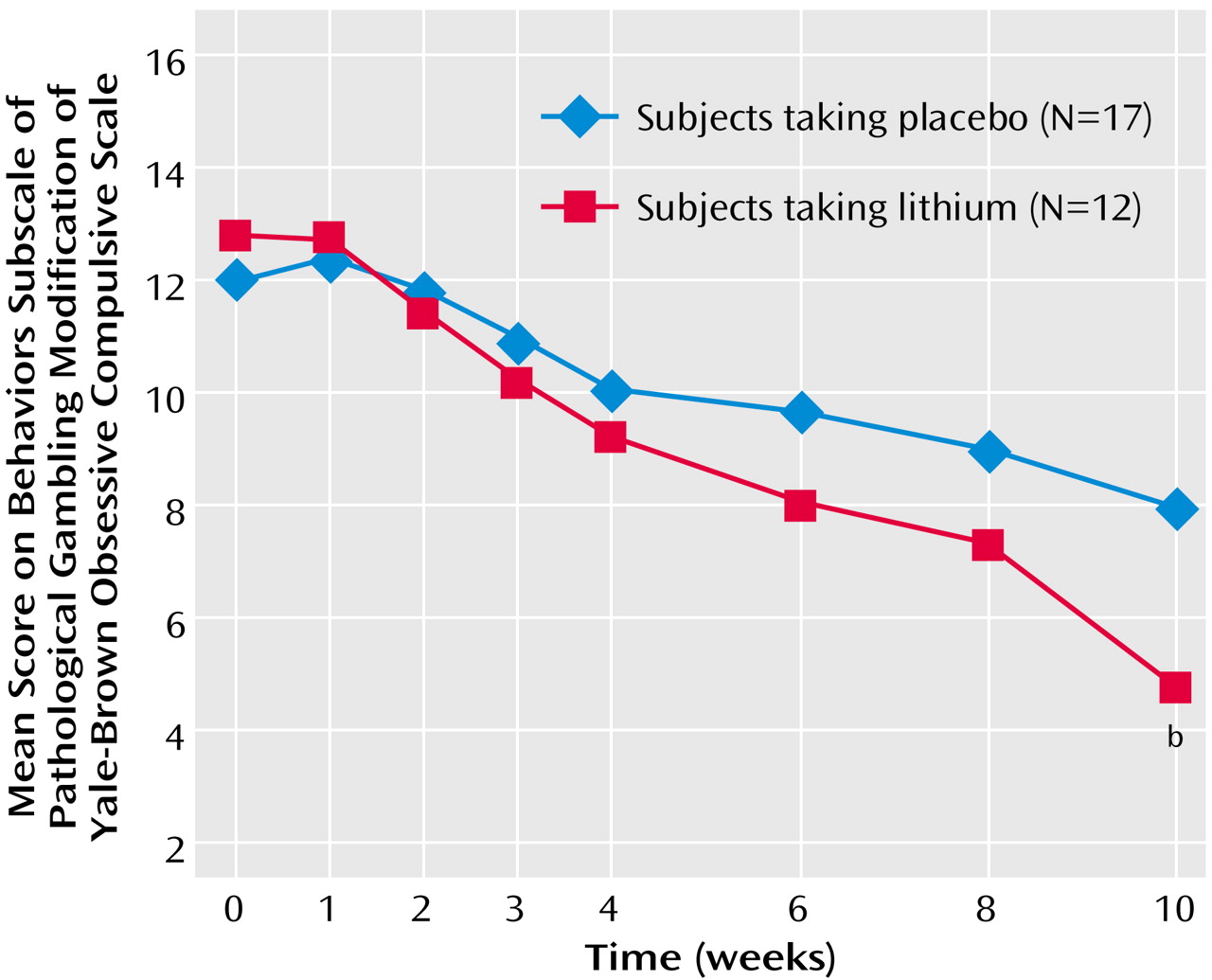

The difference between the treatment groups at endpoint was also found for both gambling thoughts/urges and behavior. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling thoughts/urges subscale showed a significant difference between the treatment groups at endpoint (F=14.49, df=1, 28, p=0.001) (

Figure 2); those in the lithium group had less severe thoughts/urges than those taking placebo (mean=5.0, SD=3.0, versus mean=9.1, SD=2.3). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling behaviors subscale also showed a significant difference between the treatment groups at endpoint (F=8.06, df=1, 28, p=0.009) (

Figure 3); those in the lithium group had less severe gambling behavior than those taking placebo (mean=4.7, SD=3.1, versus mean=7.9, SD=3.1). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling thoughts/urges subscale score for lithium was significantly lower than placebo at the last two treatment sessions (weeks 8 and 10) and for the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling behavior subscale score at the end of treatment (week 10). There was no significant correlation between lithium blood levels and change in Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling total, thoughts/urges, or behavior scores.

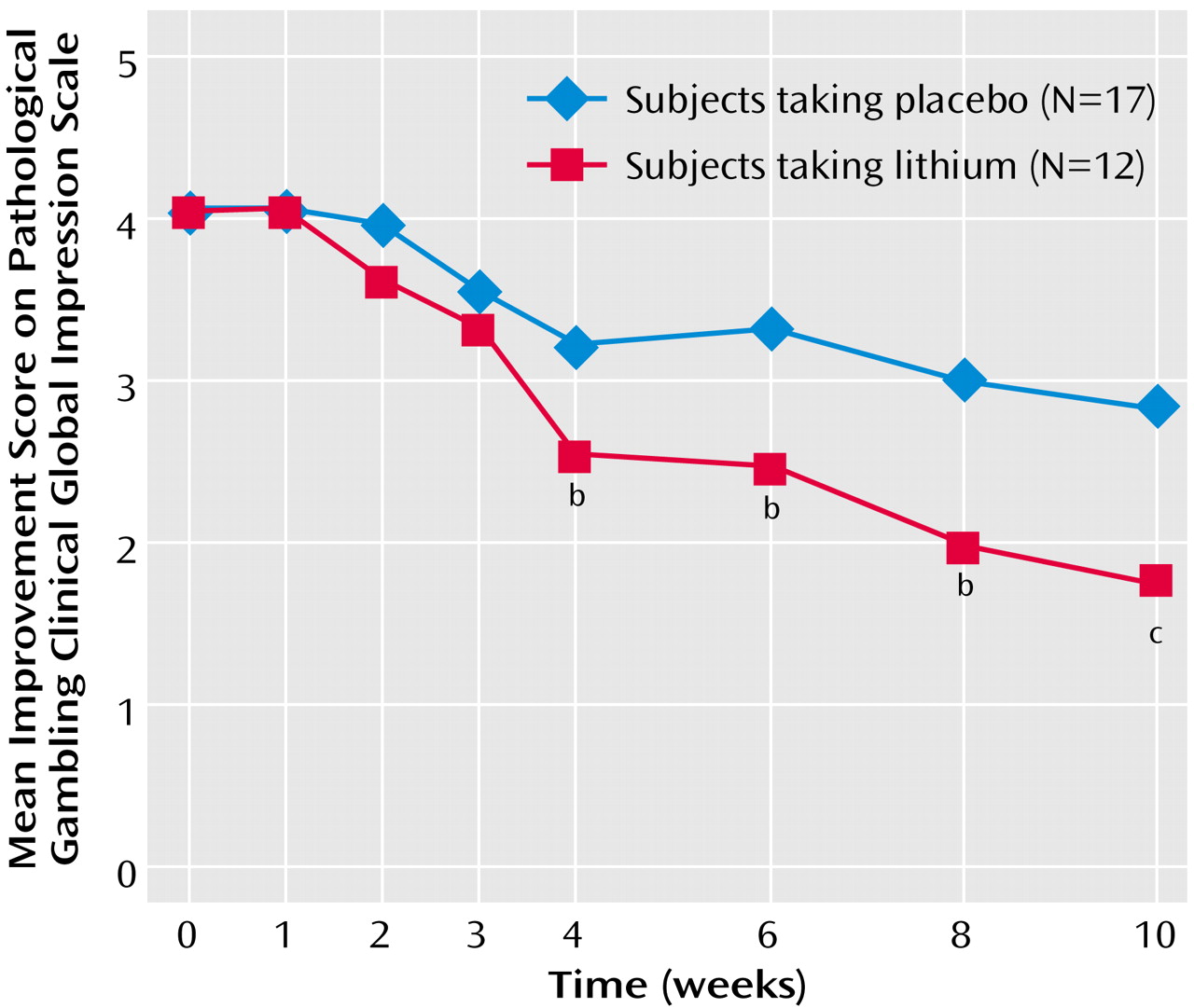

Among the completers, the CGI pathological gambling improvement scale scores for sustained-release lithium differed significantly from those for placebo at endpoint (F=7.49, df=1, 28, p=0.001). Those taking sustained-release lithium had greater improvement (lower CGI scores) than those taking placebo (mean=1.75, SD=0.62, versus mean=2.82, SD=0.88). The findings over time were consistent: among completers, both the main effect of treatment (F=11.03, df=1, 26, p=0.003) and the interaction between treatment and time were statistically significant (F=3.75, df=6, 156, p=0.002) (

Figure 4). Among completers, the lithium group had significantly lower CGI pathological gambling improvement scale scores than those taking placebo from the fourth week of treatment onward. These findings were also supported by the intent-to-treat last-observation-carried-forward analyses. At endpoint, there was a significant difference between the groups (F=7.37, df=1, 38, p=0.01). When we looked at the data over time, both the main effect of treatment (F=7.81, df=1, 36, p=0.008) and the interaction between treatment and time were significant (F=2.73, df=6, 216, p=0.03). In the intent-to-treat group, the subjects taking lithium had significantly lower CGI pathological gambling improvement scale scores in week 2 and from the sixth week of treatment onward.

Moreover, according to our responder criteria at endpoint on the CGI pathological gambling improvement scale (“much” or “very much” improved) and the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling score (35% or greater reduction in score), there were significantly more responders taking sustained-release lithium than placebo for both completer (10 [83.3%] of 12 versus five [29.4%] of 17) (χ2=8.19, df=1, p=0.004) and intent-to-treat (11 [68.8%] of 18 versus five [31.3%] of 22) (χ2=6.08, df=1, p<0.02) analyses.

No differences were found in mean score changes on the pathological gambling behavioral self-report scale between the two groups (money lost, episodes per week, time spent per episode per week). The lithium group showed a greater reduction on all items of the pathological gambling Visual Analog Craving Scale, but the differences reached significance only on the item “I feel I can control my gambling” (change scores: F=4.87, df=1, 28, p<0.04). No significant differences were found between the two groups on depression (Hamilton depression scale) or anxiety (Hamilton anxiety scale) change at the end of the trial.

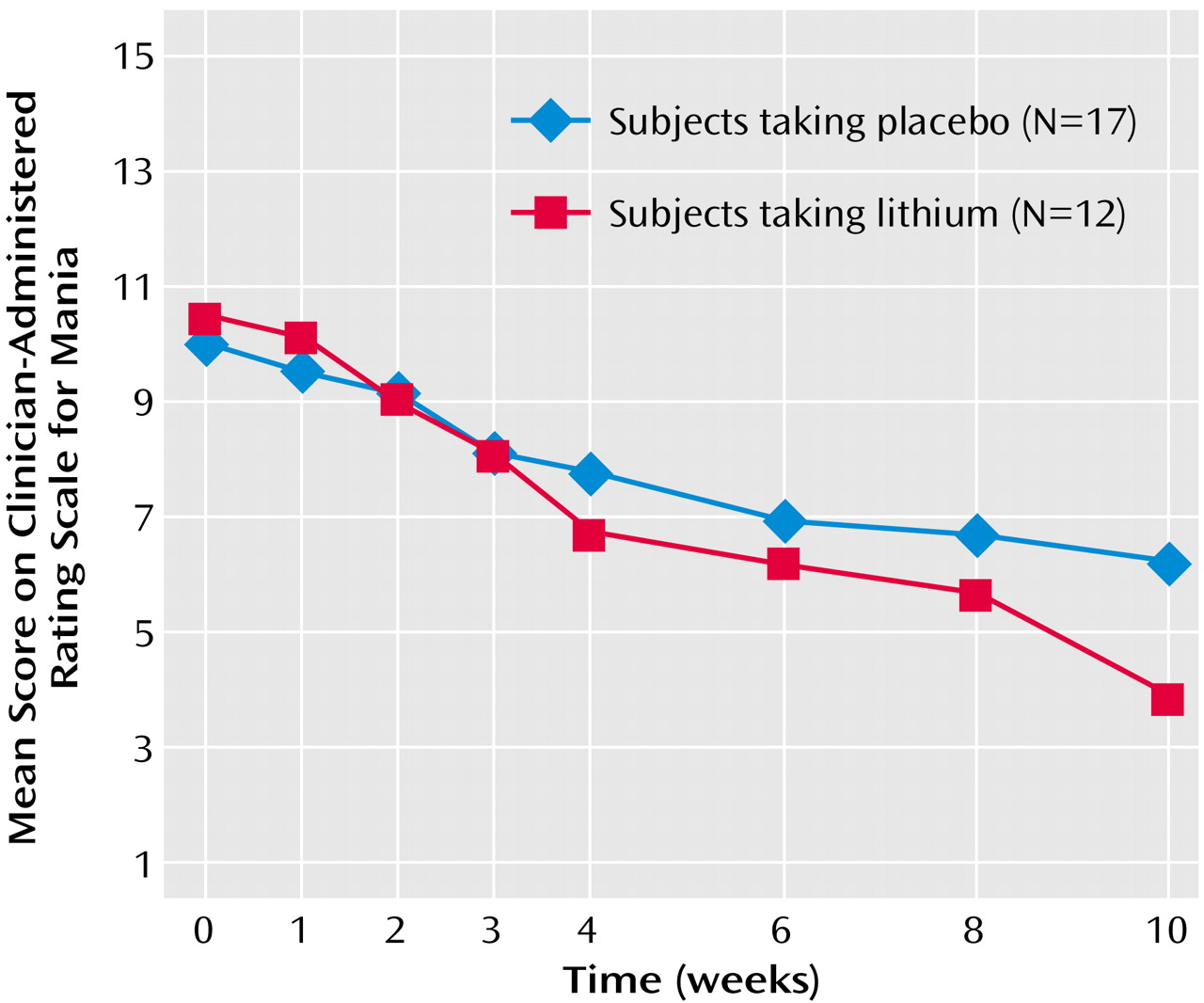

Among completers, significant improvements were noted on sustained-release lithium versus placebo in mood instability ratings by week 10 (

Figure 5) (Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania change scores: mean=6.58, SD=3.99, versus mean=3.88, SD=2.98) (F=4.82, df=1, 28, p<0.04). Of interest, in the overall group, there was a significant correlation between mean reduction in pathological gambling total score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and a mean reduction in total score on the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania (r=0.48, p=0.009). Although the correlation was relatively high among those receiving sustained-release lithium, it did not reach significance because of the smaller group size (r=0.41, p=0.20).

Completers who responded to sustained-release lithium (N=10) showed a significant reduction of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale nonplanning impulsivity subscale score (paired t=2.75, df=9, p<0.02), but no significant differences were found on the cognitive (paired t=–1.07, df=9, p=0.31) or motoric impulsiveness (paired t=–0.41, df=9, p=0.69) subscale scores. Patients who responded to placebo had no significant changes on the impulsivity subscale scores (nonplanning impulsiveness: paired t=0.93, df=3, p=0.42; cognitive impulsiveness: paired t=–0.25, df=3, p=0.82; motoric impulsiveness: paired t=0.76, df=3, p=0.50).

Clinical ratings for the 29 treatment completers over the 10-week trial are summarized in

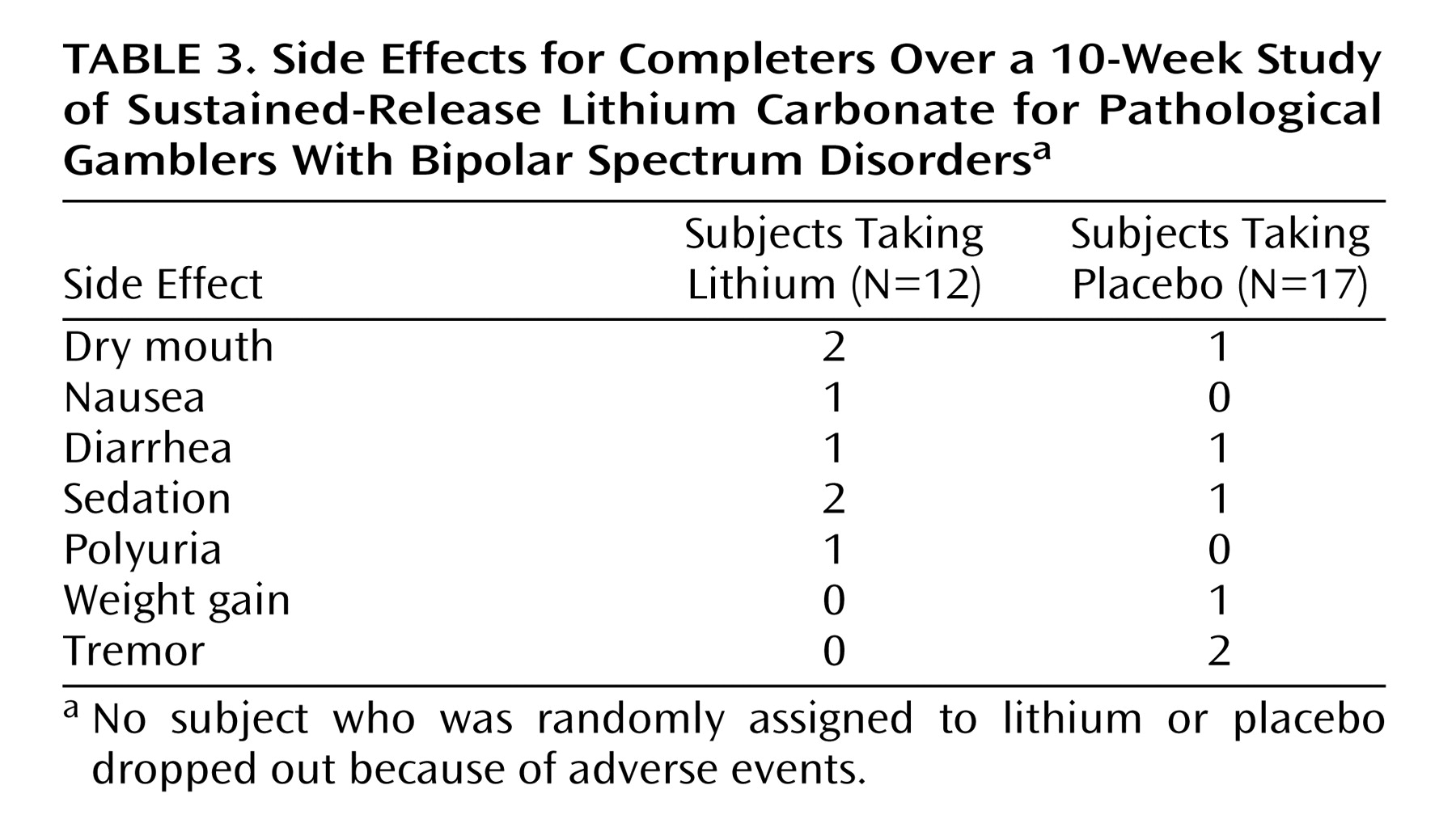

Table 2. There were no clinically meaningful differences in side effects between the lithium and placebo groups over the 10-week trial (

Table 3).

Discussion

Global Efficacy

This first placebo-controlled trial, to our knowledge, confirms the findings of previous studies in nonselected pathological gambling populations

(23,

24). Oral sustained-release lithium was found to be significantly more effective than placebo in the treatment of pathological gamblers with bipolar spectrum features. Using conservative criteria for response, the lithium group had a significantly higher proportion of responders than the placebo group, both for completer (83.3% versus 29.4%) and intent-to-treat (68.8% versus 31.3%) analyses.

Time to Response

Treatment effects took time to reach clinical significance. Global improvement was evident earlier than specific symptom improvement. The lithium group had significantly better CGI pathological gambling improvement scale scores than the placebo group, beginning with the fourth week of treatment. Change in specific pathological gambling symptoms reached statistical significance after 8 or more weeks of treatment: the groups differed significantly at the eighth and 10th weeks of treatment for the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale pathological gambling total score and the thought-urge subscale score, but the behavior subscale score differed only at the 10th week.

Specific Gambling Behaviors

Self-reports of gambling behaviors (money lost, gambling episodes per week, time spent per episode per week) did not differ between the two groups. A self-estimate of feeling able to control gambling (one of five pathological gambling Visual Analog Craving Scale items) showed significant improvement with sustained-release lithium compared to placebo at week 10. It is possible that over the short-term, 10-week trial, only a feeling of increased control over the impulse was apparent, whereas the desire to gamble persisted. Alternatively, these self-report scales may not be sensitive to short-term change. Longer-term studies are needed to clarify the evolution of these distinct cognitive aspects of impulsive gambling.

Tolerability

Dropout rates did not significantly differ between the lithium (six [33.3%] of 18) and placebo (five [22.7%] of 22) groups. Tolerability was good in both groups, and in general, adequate compliance was observed.

Affective Instability and Impulsive Gambling

Affective instability measured with the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania was in the bipolar range at baseline but was not high, yet there was significantly greater reduction of the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania score in the lithium versus placebo group. Of importance, improvements in impulsive gambling significantly correlated with increases in affective stability among the total group, underscoring the importance of affective instability in pathological gambling. However, correlation does not establish causality, and it could be postulated that a decrease in gambling could lead to an increase in mood stability. Although this relationship is based on all responders (including placebo responders), it is possible that mood stabilization by medication is also related to a decrease in gambling. An analogous finding is that of other mood stabilizers, such as valproate, decreasing impulsive aggression in cluster B personality disorders

(21). Alternatively, a specific “anti-impulsive” action of mood stabilizers can be hypothesized, considering that the reduction of gambling urges and behaviors were substantial, despite only minimal reduction on the Hamilton depression scale and the Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania in this study. Sustained mood stabilization may potentially influence the cognitive substrata of impulsive gambling behavior by reducing rapid mood swings associated with energized activity, urgency, faster decision making, and “myopia” for consequences.

The Role of Comorbidity

We suggest that the greater response to lithium versus placebo treatment in the present study reflects the importance of subtyping pathological gambling according to a comorbid symptom profile (i.e., bipolar spectrum comorbidity). Using the Mood Disorder Questionnaire at enrollment, we identified this subtype in 45.4% (40 of 88) of the pathological gamblers seeking medication treatment. Even though the current pathological gambling diagnostic criteria are valid and reliable

(34), our findings indicate that there may be significant advantages in subtyping pathological gambling patients. The identification of bipolar spectrum pathological gambling patients is relevant to the choice of pharmacological treatment. In this subtype, a mood stabilizer might have a higher probability of response than other treatments, such as SSRIs, which might exacerbate affective instability and gambling relapse

(13).

The rapid discounting of delayed rewards

(35) and “myopia” for consequences

(36) may represent the central feature of impulse-control disorders, including pathological gambling. These cognitive alterations persist outside symptomatic clinical mood disorder phases. However, impulsivity may also be a stable characteristic of bipolarity

(37), and when present in bipolar subjects with pathological gambling, it may contribute to poor insight

(38).

Limitations

The main limitation of the current study is the relatively short observation time. Only one study, by Blanco and colleagues

(17), involved a longer period of follow-up (6 months in pathological gambling subjects treated with fluvoxamine). They concluded that fluvoxamine might be a useful treatment for certain subgroups of patients with pathological gambling but found that it did not significantly differ from placebo over time. Their group showed a high placebo rate of response (59%), which is higher than our 29% placebo response, but all of their subjects were receiving concomitant self-help therapy. Since only one of our patients received psychosocial or supportive therapies during the trial, the findings of this study do not reflect an interaction between medication treatment and psychosocial treatment.

Our pathological gambling patients are not necessarily a representative group of pathological gamblers, and this may have biased our results. Our subjects were treatment seekers with more prevalent compulsive gambling behavior, more insight into their gambling, general ego-dystonic features, and bipolar features. Gamblers are more commonly characterized by non-treatment-seeking, addiction comorbidity, low insight regarding gambling behavior, and an ego-syntonic symptom profile. Furthermore, subjects recruited when seeking medication treatment could differ in motivational level from subjects enrolled in self-help or psychosocial programs. Thus, the good response to lithium we reported in our study could potentially be unique to bipolar pathological gamblers with good insight who are seeking medication treatment. It could be of interest to extend the study of bipolar spectrum pathological gambling over time and to verify the response to lithium in pathological gambling subjects recruited by different methods (as seen by Blanco and colleagues

[17], who recruited pathological gambling patients in rehabilitation programs rather than during the phase of motivation that characterizes the search for a pharmacological treatment).

Another limitation of the study is the male-female ratio of the study group: the male-female ratio was 1.4:1 in the whole group and 1:1 in the lithium-treated subgroup. The proportion of men in this study was lower than found for pathological gambling in the general population but was more likely to reflect the gender distribution of treatment seekers.

Conclusions

Sustained-release lithium may be an effective treatment in reducing both gambling behavior and affective instability in pathological gamblers with bipolar spectrum disorders. This study highlights the need to identify subgroups of pathological gambling patients with bipolar spectrum conditions because this may have important treatment implications. Thus, further studies in pathological gambling should take such comorbid conditions into account and use appropriate screening instruments to identify pathological gambling subtypes. In addition, there is a need for a longer duration of acute and maintenance treatment studies.