Epidemiologic studies of community-living elderly have shown that some anxiety disorders are common. The prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder among the elderly is 3.7%–7.4%

(1–

4), which is on par with prevalence estimates of that disorder in young adults. Furthermore, this disorder in elderly persons is associated with impairments in quality of life, increased health care utilization, and poorer functional recovery after disabling medical events (such as stroke)

(5,

6).

Despite these data, there is evidence that these anxiety disorders in elderly persons are undertreated

(7) and that treatment rates have not improved over time, as has been seen with late-life depression

(8). This lack of treatment may be secondary to the scant pharmacotherapy research on elderly persons with anxiety disorders. In the past 20 years, of the medicines available in the United States only benzodiazepines and buspirone have been studied in prospective, controlled trials, to our knowledge

(9,

10). As benzodiazepines are known to cause cognitive and psychomotor impairments in the elderly, leading to falls and fractures, they are suboptimal for older persons

(11–

17). Similarly, buspirone is not often used clinically, in part because of the high comorbidity of major depressive disorder with anxiety. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are clearly efficacious for anxiety disorders in younger adults

(18,

19); however, we know of no published studies of SSRI treatment for late-life anxiety disorders, other than a small, open-label study with fluvoxamine

(20) and our previous evaluations of comorbid anxiety in late-life depression

(21,

22). As these investigations suggested that SSRIs may be helpful in improving anxiety symptoms in elderly persons, the present study was conducted to determine the efficacy of citalopram, a commonly used SSRI, for the treatment of elderly persons with acute anxiety disorders. We hypothesized that citalopram would be superior to placebo in bringing about a clinically significant reduction in symptom burden.

Method

Adults age 60 years and older were recruited for a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled 8-week study of citalopram. Participants were recruited from the community through advertisements and referrals and from a primary care site in Pittsburgh. Primary care recruitment was done by two methods: elicitation of clinical referrals from primary care practitioners and systematic screening of patients at the practice by a sampling procedure previously described

(23). Participants who screened positive for anxiety symptoms were invited to meet with study personnel. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s institutional review board, and all participants gave written informed consent before participation. The participants underwent assessments with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, administered by raters (E.J.L., B.T.) trained for reliability. All participants were required to meet the criteria for a DSM-IV anxiety disorder, and each was given a principal diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (N=30), panic disorder (N=3), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (N=1). All participants scored 17 or higher on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(24), administered by using a structured instrument to optimize reliability

(25). Those meeting the criteria for a current major depressive episode were excluded, as such subjects were recruited for other studies by our group. Other reasons for exclusion were dementia, history of psychosis, unstable medical illness, and active alcohol or substance abuse. The participants were also assessed at baseline with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(26), the Mini-Mental State Examination

(27), and scales for instrumental and physical activities of daily living

(28).

Medication use was determined by subject report. To improve recruitment and retention of a representative clinical study group, any participant taking a benzodiazepine before the start of the study was allowed to continue taking an equipotent dose of lorazepam (maximum, 2 mg/day) as long as the dose was kept constant; no other psychotropic medication was allowed for at least 2 weeks before the beginning of the study and during the study. This decision was based on routine clinical practice, in that elderly persons are the leading consumers of benzodiazepines

(29,

30) and these medications are clinically noted to be difficult to withdraw until after patients are successfully treated with another medication.

The participants were seen weekly during the first 4 weeks of the trial and biweekly thereafter. Supportive management was offered during the trial, as described previously

(31), but no formal psychotherapy was provided. The subjects were randomly assigned to citalopram or placebo on the basis of a computer program that was developed at our institution and uses stratified permuted block randomization. Medication was provided in a double-blind fashion such that the citalopram dose was started at 10 mg/day and increased after 1 week to 20 mg/day. A further increase to 30 mg was made after 4 weeks if the participant did not achieve response by that time. Side effects were measured by using the Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser (UKU) Side Effect Rating Scale, a 48-item scale that was developed to measure somatic and psychic side effects of antidepressant treatment

(32). It has four subscales: neurologic, psychic, autonomic, and other. The scale is scored at baseline (before the start of medication) and at all follow-up visits. Side effects were also measured on the basis of the participants’ reports in response to the question “Have you had any side effects to the study medication since the last visit?” The primary outcome measures were the Hamilton anxiety scale and the Clinical Global Improvement scale (CGI), both administered by independent evaluators blind to treatment condition. Scores on the Hamilton anxiety scale were obtained at all visits. CGI improvement scores were obtained only at weeks 4 and 8. A participant was declared a responder on the basis of a 50% reduction in Hamilton anxiety score or a CGI rating of 1 or 2.

The rates of response and side effects were compared in the citalopram and placebo groups by using two-tailed chi-square tests and linear modeling. Because a greater proportion of men were randomly assigned to the placebo group, a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test

(33) was performed to test group differences while stratifying by gender. Following an intent-to-treat principle, for participants who dropped out we used data from the last available visit to determine response. The two groups were compared in terms of change in Hamilton anxiety score by using a mixed-effect repeated-measures linear model (intercept and time were random components). The same model was used to compare the groups in terms of side effects as assessed with the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale.

Results

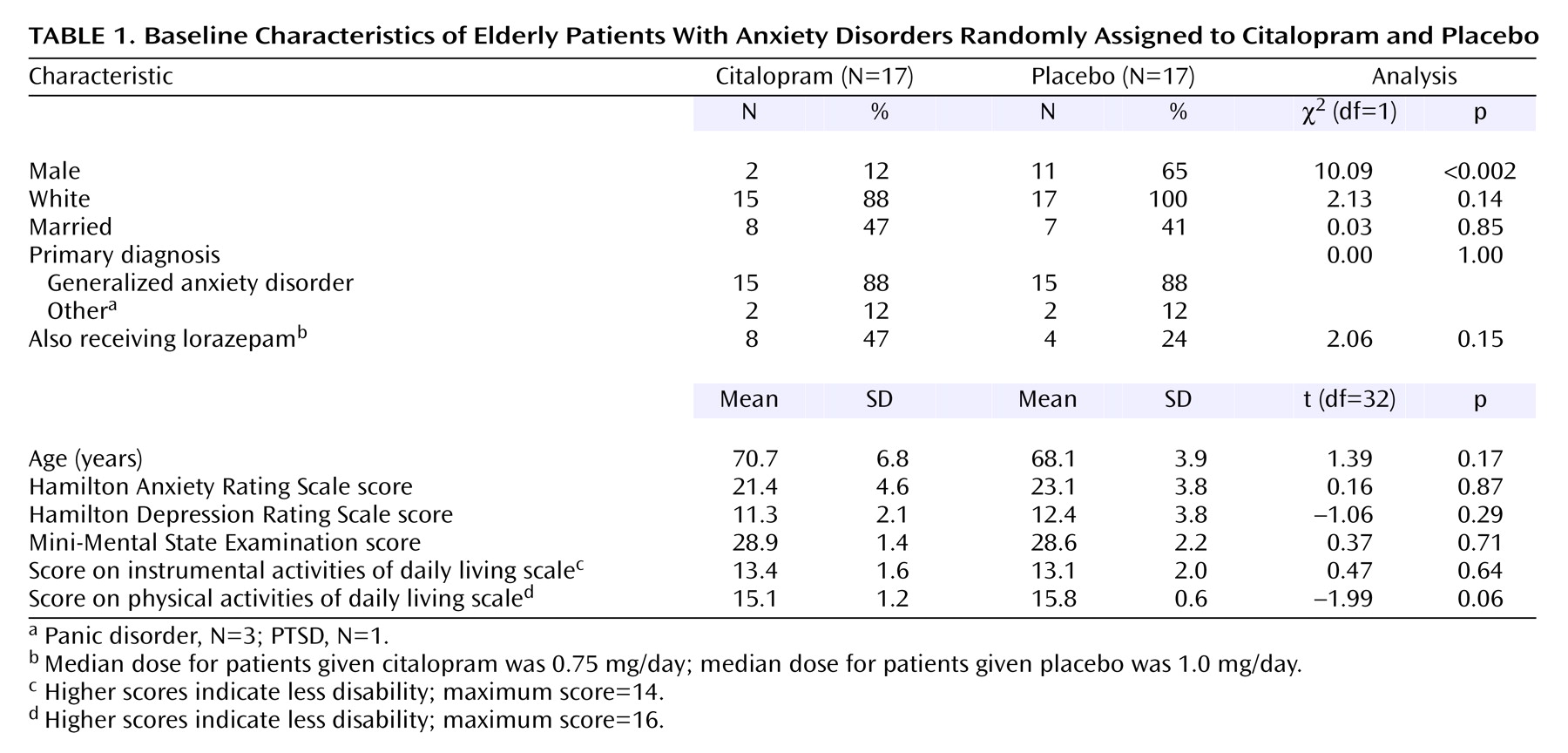

We screened or assessed a total of 791 elderly persons from a primary care practice or the community. From this group, 47 persons signed consent forms and were extensively evaluated for anxiety disorders (17 responded to advertisements or word of mouth, 21 were referred, and nine were primary practice patients). Of these 47 participants, 10 refused randomization and three were excluded (one had spontaneous improvement of anxiety before randomization, one did not meet the diagnostic criteria for any anxiety disorder other than specific phobia, and one was in a major depressive episode). Thus, 34 participants were randomly assigned, stratified by diagnosis, 17 each to citalopram and placebo. Comorbidity was common: of the 30 subjects with a primary diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, 17 had at least one current or past comorbid disorder (current or past specific phobia, N=8; past major depressive disorder, N=6; current panic disorder, N=5; current or past social phobia, N=3; current or past obsessive-compulsive disorder, N=2; current depressive disorder not otherwise specified, N=1; current hypochondriasis, N=1; current dysthymic disorder, N=1; current PTSD, N=1). Of the three subjects with a primary diagnosis of panic disorder, all had additional disorders (current or past social phobia, N=3; current or past specific phobia, N=2; current dysthymic disorder, N=2; past PTSD, N=1). The subject with PTSD also had specific phobia and past major depressive disorder. There were no differences in demographic characteristics or baseline clinical measures except for sex, with more men randomly assigned to placebo (

Table 1).

Most of the participants—29 (85%) of 34—completed the 8-week study. Five dropped out before week 8 (three taking citalopram and two taking placebo), only one because of side effects (one patient receiving citalopram experienced intolerable sedation after one dose). Eleven of the 17 citalopram-treated participants responded, for a response rate of 65%, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 42%–87%, compared to a response rate of 24% (95% CI=3%–44%) for the placebo group (four of 17 participants). These rates were found by using either response criterion: 50% reduction in Hamilton anxiety score or CGI rating of 1 or 2 (i.e., all responders met both response criteria). The probability of response was significantly greater for the participants assigned to citalopram (χ

2=5.86, df=1, p<0.02), for a relative risk of response of 2.57 for citalopram (95% CI=1.05–6.27). Further, the difference in response rates remained significant when we controlled for gender (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test: χ

2=4.22, df=1, p<0.04; Breslow-Day test for homogeneity of the odds ratios: χ

2=0.46, df=1, p=0.50, which demonstrated that the assumptions for the statistical test were met). When we evaluated response in terms of reduction in Hamilton anxiety score to 10 or less, we found that eight of the 17 citalopram-treated subjects, versus three of the 17 who received placebo, attained this level of remission of symptoms (χ

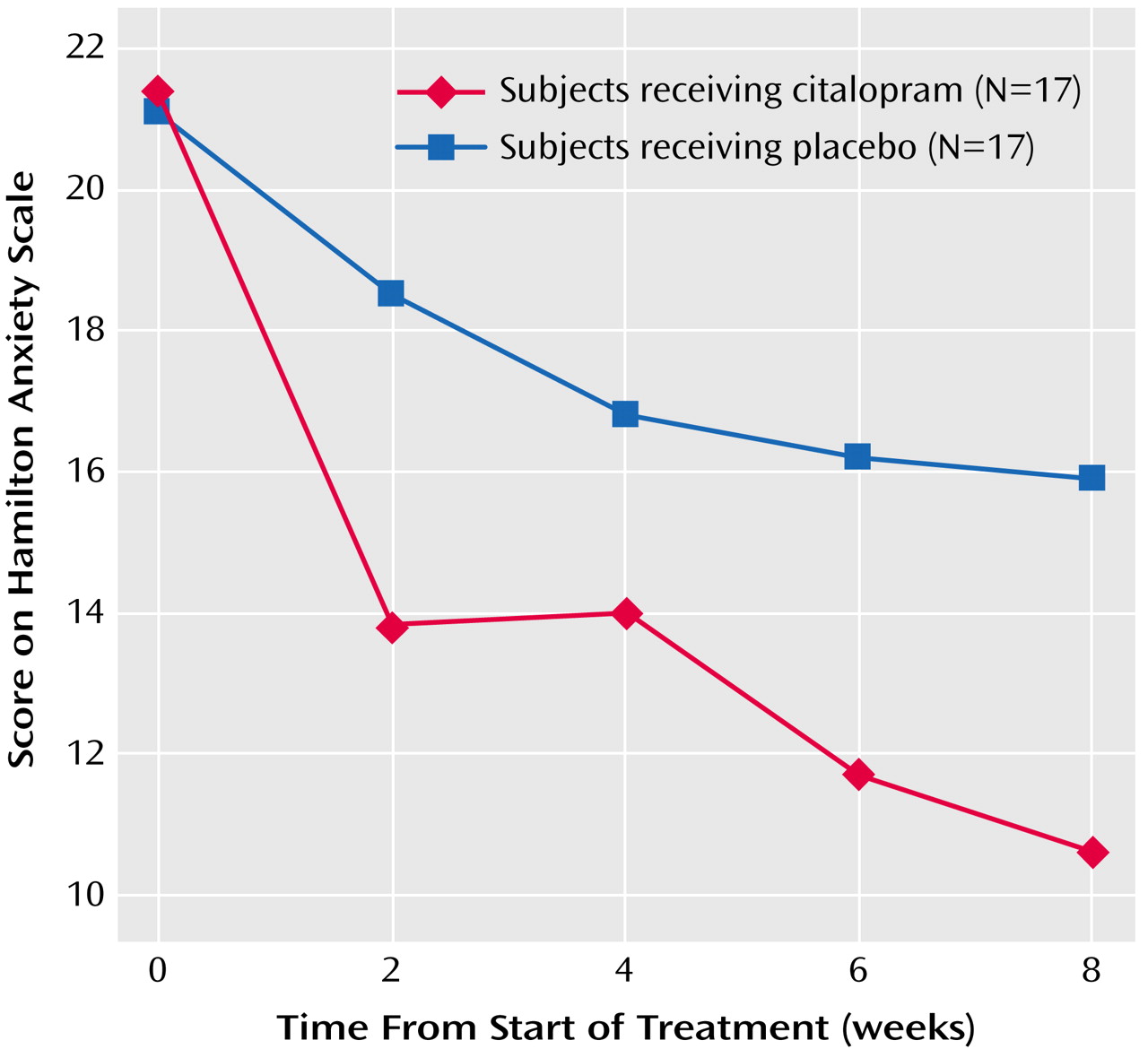

2=3.36, df=1, p=0.07). Similarly, a mixed-effect linear model of Hamilton anxiety scale scores over the 8 weeks of treatment demonstrated a significant time effect (F=34.90, df=1, 30, p<0.0001), indicating a general decrease of anxiety over time, and a treatment-by-week interaction (F=3.79, df=1, 145, p=0.05), indicating greater improvement in anxiety in the citalopram group than in the placebo group (

Figure 1); this improvement showed an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.79 (95% CI=0.01–1.46)

(34).

Because most participants had generalized anxiety disorder, we repeated the same analysis for only those with generalized anxiety disorder. We again found a significant difference in response rate between citalopram (10 of 15, or 67%) and placebo (four of 15, or 27%) (χ2=4.82, df=1, p<0.03).

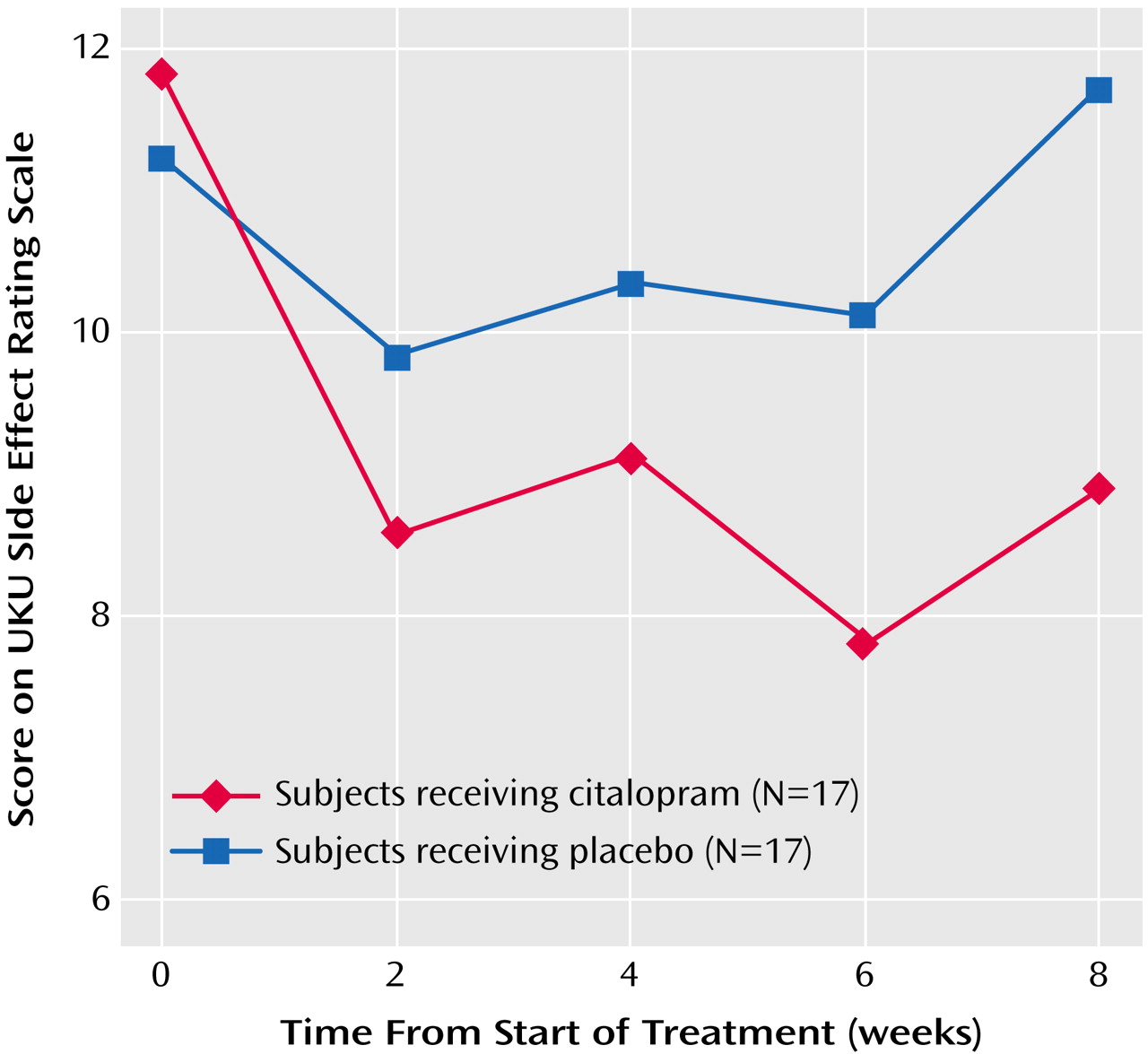

The rates of reported side effects were similar in the two groups. Twelve of the 17 citalopram-treated participants complained of at least one side effect, versus nine of the 17 placebo-treated participants. The most common side effects in both groups were dry mouth, nausea, and fatigue (N=3 each for the citalopram group and N=3, N=2, and N=2, respectively, for the placebo group). We also assessed side effects with the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale. A mixed-effect linear model of the total scores over time showed a nearly significant group-by-week interaction (F=2.99, df=1, 144, p<0.09), suggesting a decrease in side effects in the citalopram group and no change over time in the placebo group (

Figure 2). An evaluation of the four subscales of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale by mixed-effect linear models did not show any significant differences between the citalopram and placebo groups (data not shown).

As 12 (35%) of the 34 subjects received fixed doses of coprescribed lorazepam, we compared the response rates of those receiving and not receiving lorazepam. We found no differences in response attributable to this medication (data not shown). Of these 12 subjects, two had been switched to lorazepam from alprazolam, rather than continuing previous treatment; both of these subjects were randomly assigned to citalopram, and both exited the study early as nonresponders.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a controlled prospective study of an SSRI for treating anxiety disorders in elderly persons. Our data suggest that citalopram is efficacious in the management of acute anxiety disorders in this age group, as the participants had a clinically and statistically significant improvement in anxiety symptoms over 8 weeks of treatment. The improvement in symptoms cannot be attributed to coprescription of a benzodiazepine, which was kept at a steady and low dose during the study in those who were already taking benzodiazepines.

These data are consistent with findings by Katz et al.

(35), who found in a retrospective analysis of industry data that extended-release venlafaxine was as efficacious and well tolerated in elderly as in younger persons. In the present study, citalopram was well tolerated, with side effects similar to those for placebo. The reduction in overall side effects (as measured by the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale) during treatment with citalopram may reflect improvement in anxiety-related somatization, as has been seen in the treatment of late-life depression with comorbid anxiety

(21).

Three limitations should be noted. First, our small study group and the preponderance of recruitment through advertisements and referrals may limit the generalizability of the results; for example, the confidence interval of the effect size is wide. Second, our randomization failed to produce equal gender proportions in the citalopram and placebo groups, and while we did statistically control for this, these results may nevertheless reflect lower treatment responsiveness of anxiety disorder symptoms in men than in women. Finally, while our study group had some diagnostic heterogeneity, the vast majority of participants had generalized anxiety disorder, reflective of the high prevalence of this diagnosis in elderly persons, and all participants met the symptomatic threshold (based on Hamilton anxiety scale score) for moderate to severe symptoms. Because of these limitations, we recommend that these results be replicated in a setting representative of anxious nondepressed elderly persons (such as in primary care) with a larger study group so that effect sizes can be more precisely estimated and subgroup analyses can determine the generalizability of treatment response

(36). Notwithstanding these limitations, this study suggests that, as in younger people, SSRIs are efficacious and well tolerated in the treatment of anxiety disorders in elderly persons.