Sample

These data were collected as part of the Screening Across the Lifespan Twin study, based on the Swedish Twin Registry

(12), which is formed from a nearly complete registration of all twin births in the country. Data collection was performed with a computer-assisted telephone interview, the purpose of which was to screen all twins regardless of their previous participation in activities of the Swedish Twin Registry or the vital status of their twin partner. Efforts were made to interview members of a pair within a month of each other. The most recent information on last name and address was linked to the telephone company’s files to obtain telephone numbers. Introductory letters describing the study were sent to a random sample of approximately 1,000 twin pairs each month. All screening data were collected over the telephone by trained interviewers (with adequate medical background) using a computer-based data collection system. If the twin was unable to be interviewed, portions of the interview were conducted with an informant (although no data on major depression were collected in these informant interviews).

The cohort of twins born between 1886 and 1958 was contacted between March 1998 and January 2003. Of the 61,005 living individuals age 42 or older at the time of screening, 44,919 (73.6%) responded. Of those who did not respond, 9,366 refused (15.4% of the cohort) while the others were not able to be traced or were not interviewable. The present analyses are based on 42,161 twins excluding 1) those interviewed by proxy, 2) those who terminated the interview prior to the depression section or for whom the interview improperly skipped out of the depression section, and 3) members of pairs with uncertain zygosity. According to standard Swedish practice, informed verbal consent was obtained prior to interview. This project was approved by the Swedish Data Inspection Authority, the Ethics Committee of the Karolinska Institute, and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California. As detailed elsewhere

(12), zygosity was assigned by using standard self-report items, which, when validated against biological markers, were 95%–99% accurate.

Assessment Methods

Interviews were conducted by using the computerized Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) adapted from its original design for 12-month prevalence to assess lifetime prevalence

(13). In the CIDI-SF, the evaluation of major depression was simplified by the elimination of criteria A5 (psychomotor agitation/retardation) and C (distress or impairment) and the simplification of criteria A3 (eliminating loss/gain of appetite) and A4 (eliminating hypersomnia). The version of the CIDI-SF adapted for this study contained a “skip-out” for individuals who, when asked about episodes of sad mood in the last year, volunteered they were taking antidepressants. The assumption was that such individuals were likely positive for a history of major depression but were unlikely to manifest symptoms in the last year because of treatment. Because of a procedural oversight, this skip-out was not eliminated when the CIDI-SF was adapted for lifetime prevalence.

In validating the CIDI-SF criteria for major depression against 1-year prevalence data with the full Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Kessler and Mroczek (unpublished written communication, Feb. 22, 1994) recommend using a cutoff of four or more of eight criteria contained in the CIDI-SF. We simulated the CIDI-SF assessment of major depression in our sample of 7,521 personally interviewed twins from the Virginia Twin Registry for whom we had a complete set of items for DSM-III-R adapted from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(14). Compared to the full criteria, we found the following estimates of sensitivity, specificity, and kappa: three or more criteria: 0.998, 0.865, 0.81 (SE=0.01); four or more criteria: 0.956, 0.954, 0.90 (SE=0.01); and five or more criteria: 0.759, 1.000, 0.81 (SE=0.01). Our data also suggested that four or more criteria for major depression from the CIDI-SF produced the optimal cutoff.

The sample contained 8,056 twins who completed the major depression section and met the criteria for major depression and 322 twins who skipped out of the section because they volunteered a history of antidepressant usage. We assessed whether a history of “taking antidepressants” was a valid substitute for a diagnosis of major depression by examining risk for major depression in co-twins of all twins with 1) neither a diagnosis of major depression nor a history of antidepressant usage, 2) a diagnosis of major depression, and 3) a history of antidepressant usage. When the analysis controlled for zygosity, age, and sex, the risk for major depression significantly differed across the three groups (χ2=162.55, df=2, p<0.0001). The three post hoc contrast analyses indicated that both group 2 (χ2=156.90, df=1, p<0.0001) and group 3 differed significantly from group 1 (χ2=9.01, df=1, p=0.003) but that groups 2 and 3 did not themselves differ significantly (χ2=0.16, df=1, p=0.69). With respect to risk for major depression in the co-twin, “taking antidepressants” was equivalent to having been assigned a diagnosis of major depression. Therefore, we considered as affected twins who either fulfilled the criteria for major depression or volunteered that they were taking or had taken antidepressants.

Statistical Analysis

The goal of our genetic analysis was to decompose the variance of the liability to major depression into its genetic and environmental components. We assumed that twin resemblance arises from two latent factors: 1) additive genes (A), contributing twice as much to the monozygotic as to the dizygotic twin correlation (because monozygotic twins share all, while dizygotic twins share on average half, their segregating genes), and 2) shared or “common” environment (C), which contributes equally to the correlation in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. In addition to common environment (environmental experiences that make twins similar in their liability to major depression, such as parental rearing practices or social class), the model also contains individual-specific environment (E), which reflects measurement error and those environmental experiences (such as traumatic life events in adulthood) that make members of a twin pair different in their liability to major depression.

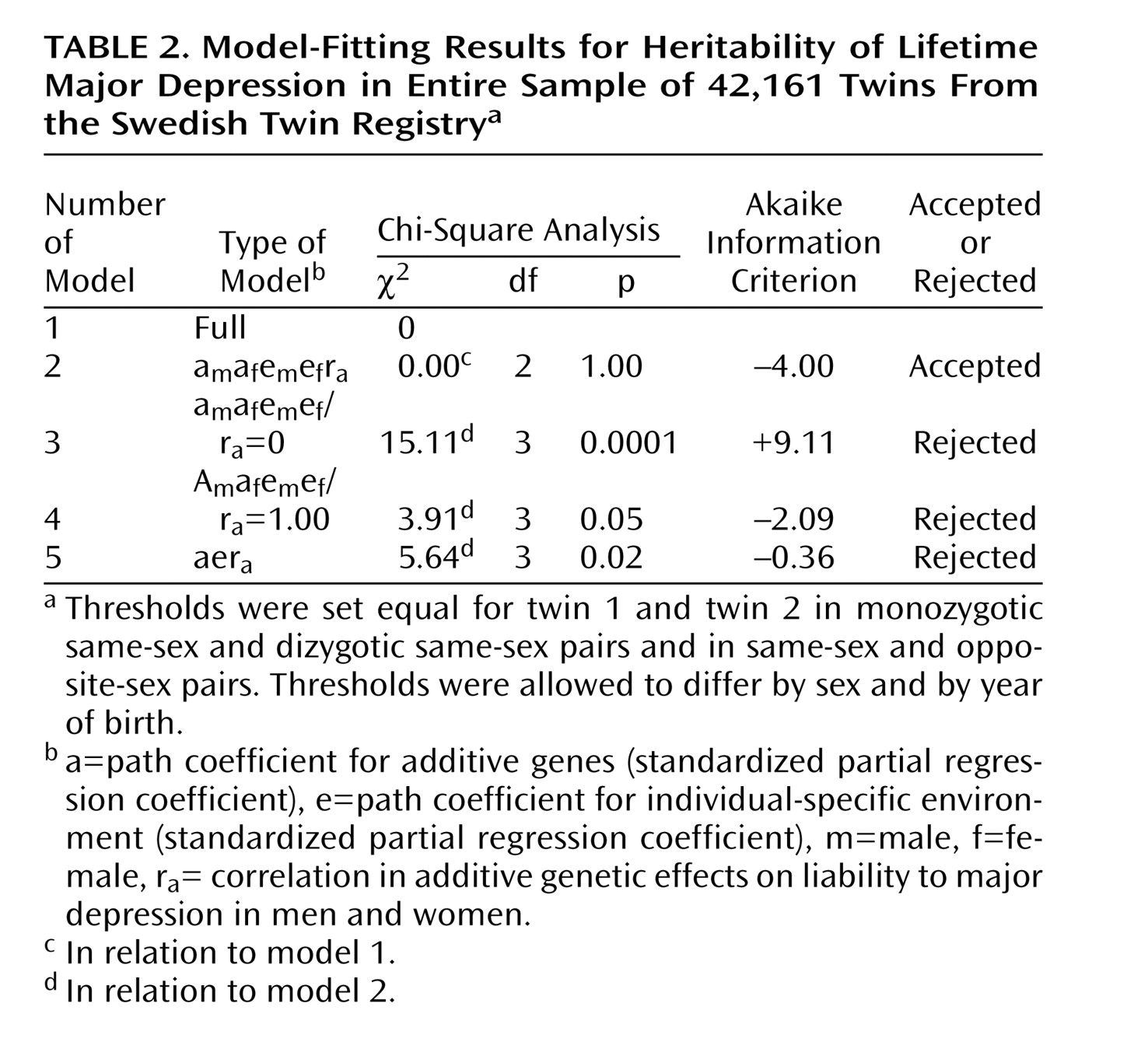

Using the software package Mx

(15), we fit models by the method of maximum likelihood to data from all individual twins, including those without an interviewed co-twin. This method reduces the impact of cooperation bias and is a binary data maximum likelihood application of the “missing at random” principle expounded by Little and Rubin

(16). Because prevalence rates changed substantially as a function of age in this sample, our calculation of tetrachoric correlations and model fitting included an age-dependent threshold that “subtracted out” the twin resemblance due to their perfect correlation for year of birth.

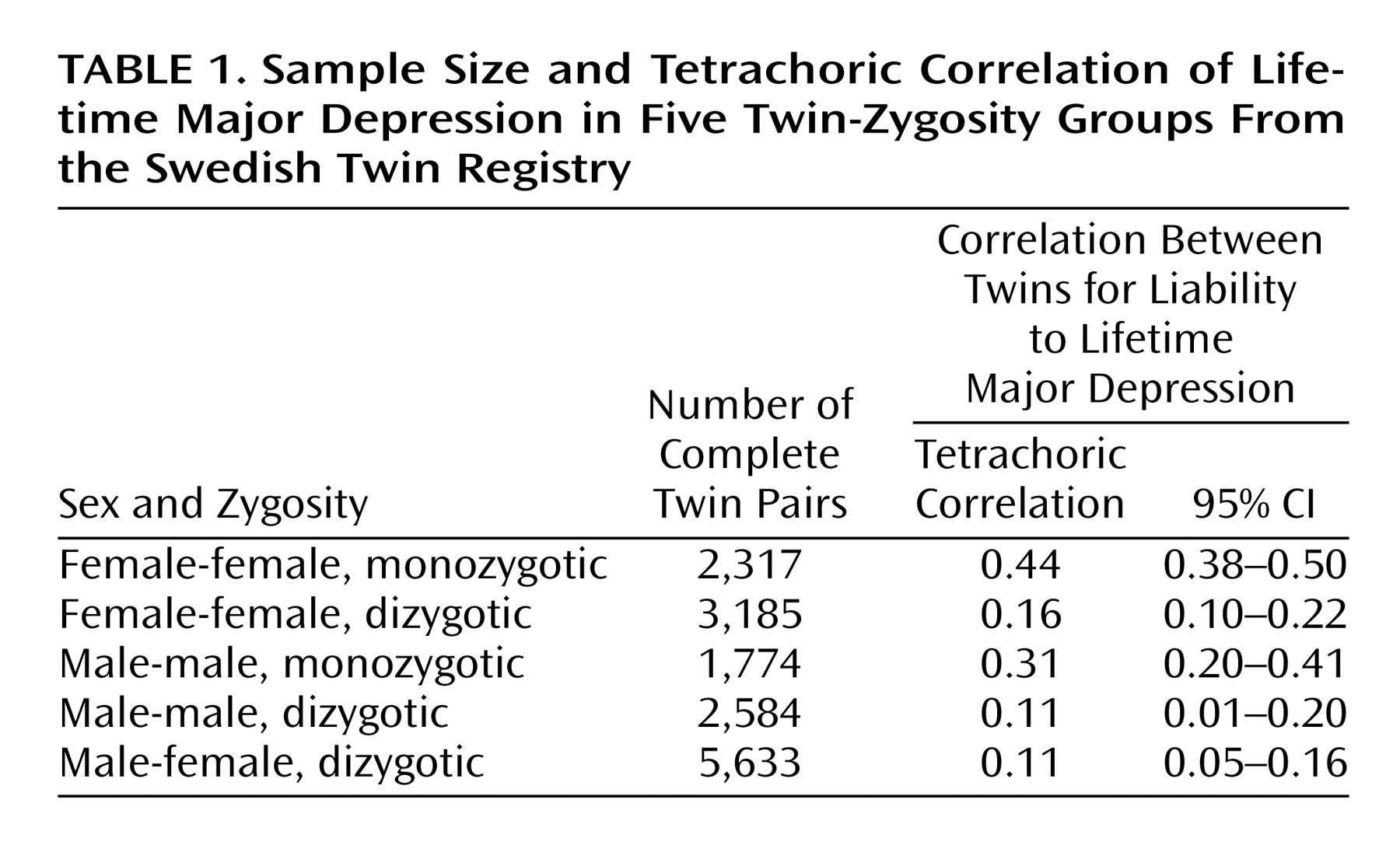

Analyzing all five twin-zygosity groups (i.e., female-female monozygotic and dizygotic, male-male monozygotic and dizygotic, and opposite-sex dizygotic pairs) enabled us to examine two distinct sex effects. The quantitative question asks whether the magnitude of genetic effects on major depression is the same in men and women. The qualitative question inquires whether the genetic risk factors for major depression in men and women are the same. The latter question involves the estimation of the parameter ra—the correlation in the additive genetic effects on the liability to major depression in men and women. If ra, or the genetic correlation, is zero or one, then the genetic factors that influence major depression in males and females are, respectively, entirely unrelated or identical.

Twice the difference in log -likelihood between the two models yields a statistic that is asymptotically distributed as chi-square with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in their numbers of parameters. We used the Akaike information criterion

(17,

18) for model selection. The lower its value, the better is the balance between explanatory power and parsimony.

Our analyses assumed that the exposure to etiologically relevant environmental risk factors is equally correlated in monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs. To test this equal environment assumption, we examined the available indices of the similarity of childhood environment (number of years living together in home of origin) and adult environment (current frequency of contact or personal meetings with the co-twin) to determine whether monozygotic twins may have had more similar environmental experiences than dizygotic twins

(19). Using logistic regression while controlling for zygosity and sex, we tested, in same-sex pairs only, whether the mean score on these environmental measures predicted pair concordance for major depression.