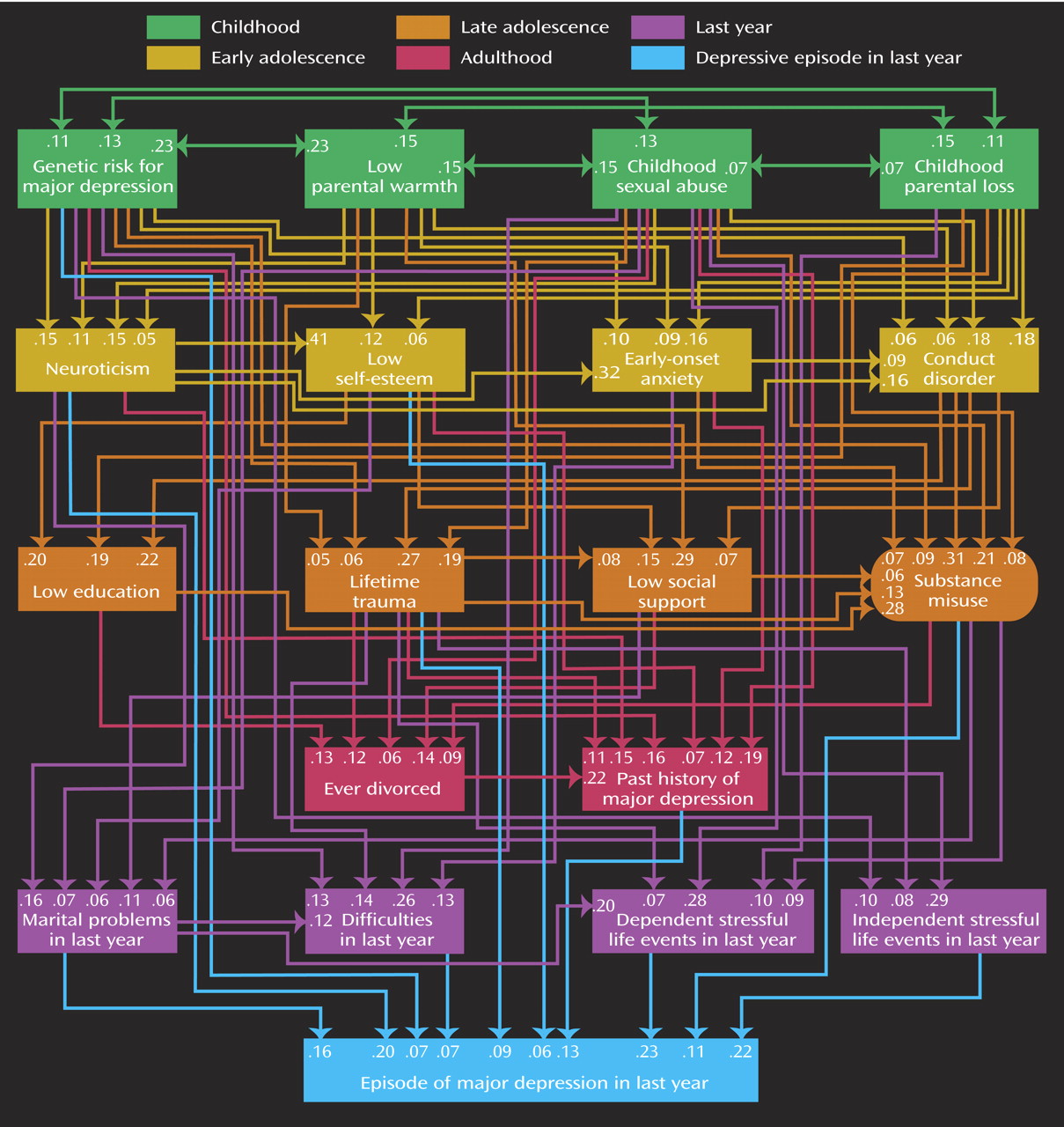

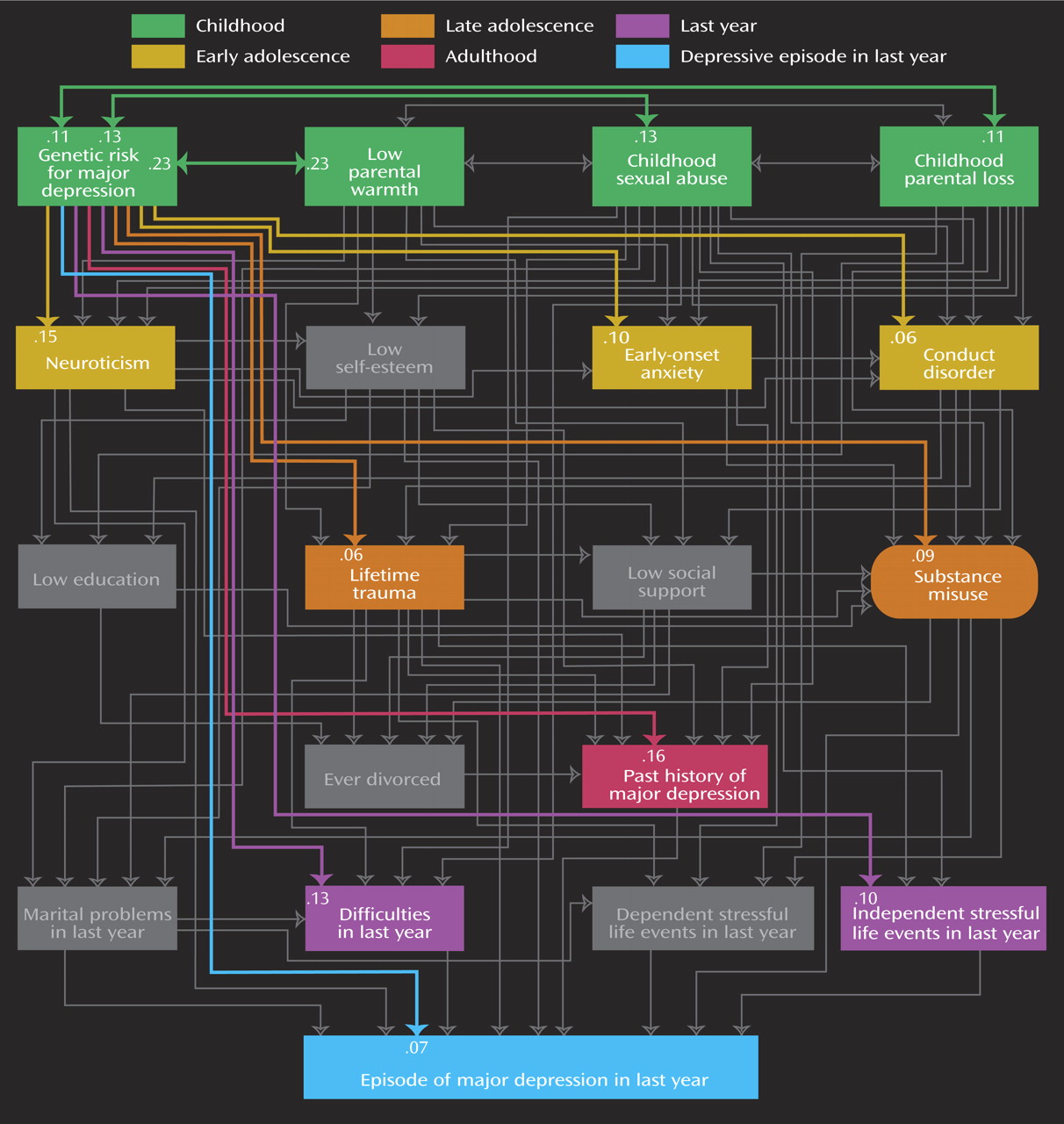

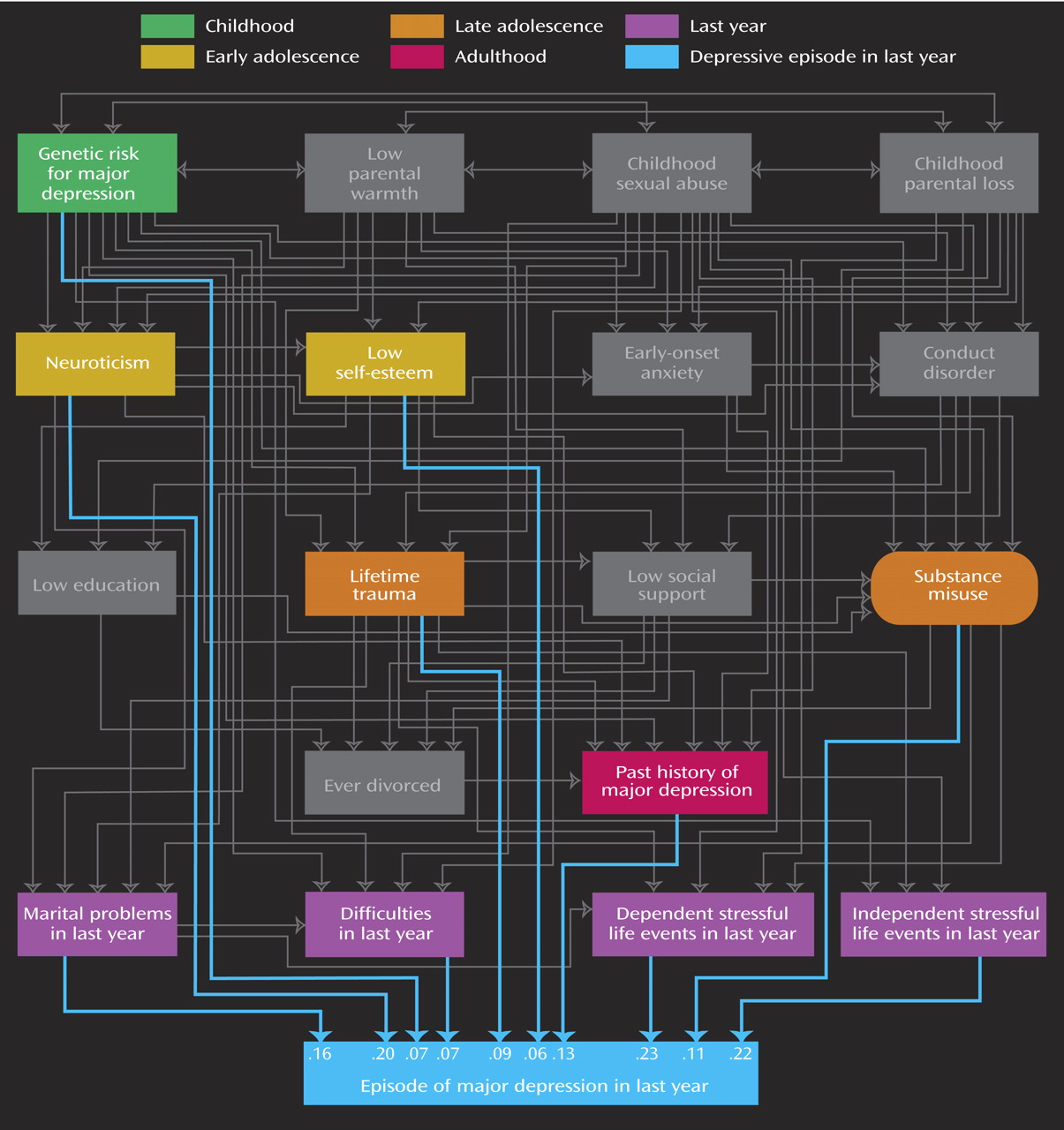

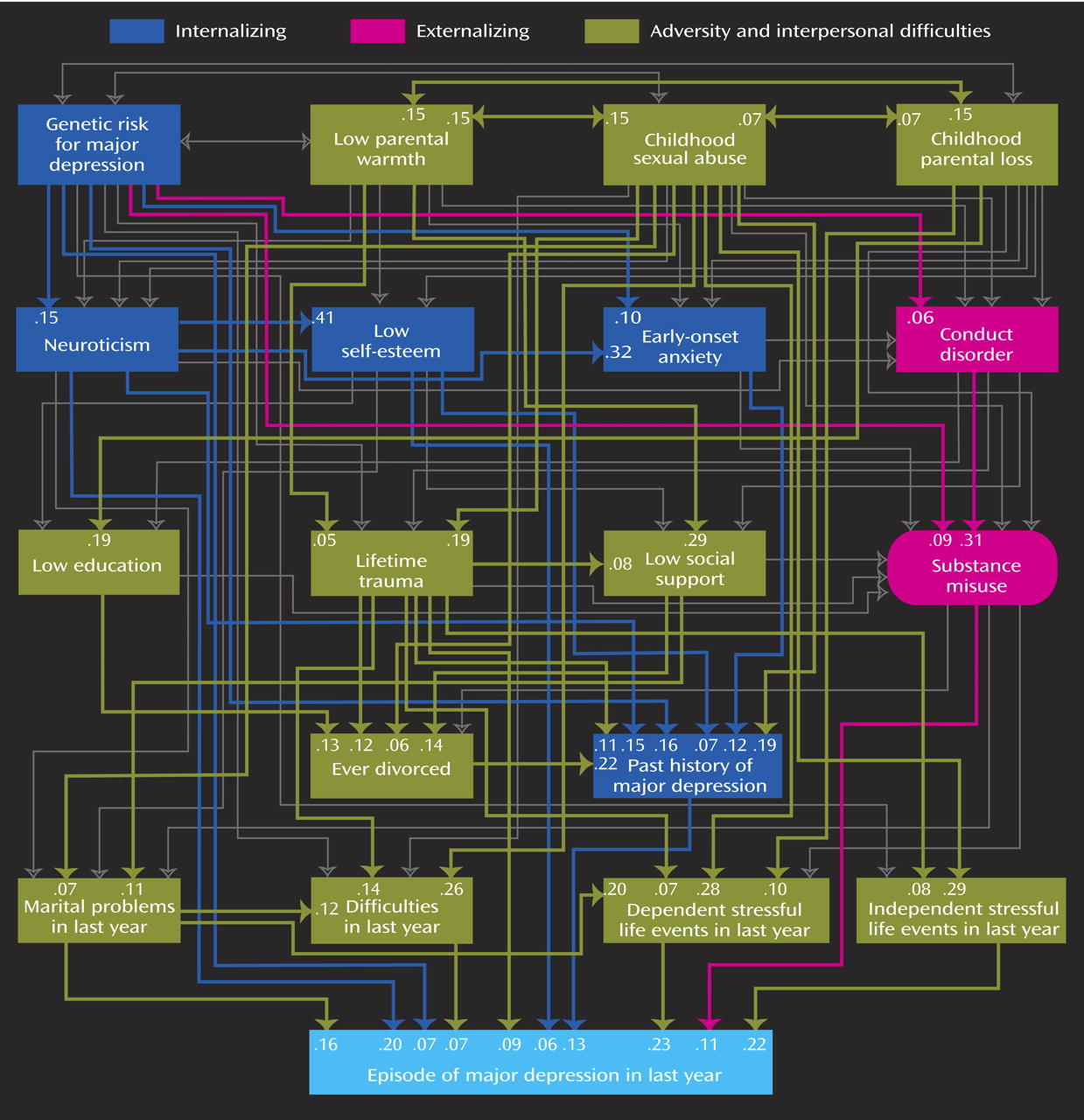

We sought to derive empirically an integrated, developmental model for the etiology of major depression in men using methods as comparable as possible to those in our previous study of women

(2). Given the complexity of our model and the sample size to which it was applied, its fit was excellent, demonstrating a good balance of parsimony and explanatory power.

Although our current model was slightly less successful at predicting risk for major depression in men (48.7% of the variance) than our prior model in women (52.1%)

(2), the general outlines of the results were similar in the two sexes. The present findings, in an independent sample, obtained with comparable measures and methods, broadly replicate our previous results in women.

Methodological Limitations

Since we previously outlined methodological limitations of our modeling

(2), we review them here briefly. First, these models assume a causal relationship between predictor and dependent variables. The validity of this assumption varies across our model. Some of the intervariable relationships that we assumed take the form of A → B may be truly either A ← B or, more likely, A ↔ B.

Second, a number of variables were assessed by long-term memory and may be subject to recall bias. Within the limits of a two-wave design with a cohort in early to middle adulthood, we tried to minimize this problem by using multiple reporters (e.g., for parental warmth), recording objective events less susceptible to recall bias (e.g., parental loss, divorce, educational level), assessing variables prospectively (i.e., at our first interview) when possible, and measuring a number of key constructs over the last year (including stressful life events and depressive onsets), thereby reducing the time frame of recall.

Third, the sequence of variables in our model was only approximate. We evaluated the validity of our ordering by fitting 10 additional models in which we took more “upstream” variables and moved them “downstream.” In nine of these, the model fit deteriorated, often dramatically. In one model, the fit improved modestly but contained implausible causal assumptions (i.e., that low self-esteem, neuroticism, and low social support cause parental loss). In aggregate, these analyses support the appropriateness of the sequence of variables in our model.

Fourth, our model assumes that multiple independent variables act additively and linearly in their impact on risk for major depression. This is unlikely to be true. In this sample, for example, high levels of neuroticism increased sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events

(20).

Fifth, this sample consisted of adult white male twins born in Virginia. With respect to the rates of psychopathology—including depressive symptoms and major depression—twins are probably representative of the general population

(21,

22). Furthermore, our 1-year prevalence of major depression (6.1%) was midway between that reported in the original National Comorbidity Survey (7.7%)

(23) and that found in the recently completed National Comorbidity Survey replication (4.7%) (personal written communication, R. Kessler, October 2005), suggesting that our sample is likely to be broadly representative of American men. However, our results might differ in men from other ethnic groups.

Sixth, our model probably underestimates the impact of genetic factors on the etiology of major depression as our measure of genetic risk was indirect and we did not include the well-known genetic influences on other key variables, such as neuroticism, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, and substance use.

Seventh, differences between the present model and that presented previously in women

(2) could arise from four sources that cannot be easily distinguished: 1) true differences, 2) variation in measures, 3) greater power in the male sample, and 4) statistical fluctuations. Our measure of “low parental warmth” is probably less potent than our parallel variable in our female sample (disturbed family environment) because it is a poorer measure of early family problems. Modest differences between the two models should not be overinterpreted. For example, a direct path from substance misuse to last-year major depression is seen in men but not women

(2). However, this may not be a major difference because in both sexes, conduct disorder and substance misuse were strongly related. In women, conduct disorder but not substance misuse predicted depressive onsets. In men, the opposite effect was seen.

Conclusions

Major depression in men is a complex, multifactorial disorder, the liability to which is influenced by a broad array of risk factors that act at different stages of development. Variables that influence risk for major depression in men include genetic and temperamental factors, psychosocial adversity both early in life and in adulthood, childhood anxiety and conduct disorders, and substance misuse. A comparison of these results with those obtained previously in women, by using parallel methods and measures

(2), suggests only modest differences. While a few variables appeared to differ meaningfully across the two, the overall pattern of results was similar. These results suggest that, from an etiologic perspective, major depression is largely the same disorder in men and women.

As in women, these results further illustrate the complexity of the “gene to phenotype” pathway. Individuals at elevated genetic risk for major depression are likely to be exposed to higher rates of childhood adversity, to have higher levels of neuroticism, to have higher rates of early-onset anxiety disorder and substance misuse, and to select themselves into more difficulties and stressful life events in adulthood, all of which in turn increase risk for a depressive outcome. Genes almost certainly influence risk for major depression by traditional “inside the skin” physiological pathways (i.e., by altering susceptibility to dysphoria as instantiated in selected brain systems). However, “outside the skin” pathways, whereby susceptibility genes alter exposure to drug abuse and psychosocial adversities, are also likely to prove critical. In multifactorial disorders such as major depression, gaining a deeper understanding of etiology will be substantially aided by examining the joint effects of multiple risk factor domains.