For every medical condition, it is important to consider the goal of treatment when initiating care. For many medical disorders, the goal of treatment is often clear-cut. For example, the goal of treatment for epilepsy is for the patient to be seizure free; for hypertension, the goal is to reduce blood pressure to the “normal range”; and for acute infections, the goal is to return to the preinfectious state. Clearly identified goals of treatment are equally important in the treatment of depression

(1). An increasing number of experts in the treatment of depression have suggested that achieving remission should be viewed as the primary goal

(2–

8). These recommendations are based on studies that have consistently demonstrated that depressed patients who have responded to treatment but failed to achieve symptomatic remission continue to experience psychosocial impairment and have a higher likelihood of recurrence of a full depressive syndrome

(9–

14).

Twenty years ago different terms were used to describe the course of depression, and even when investigators used the same terms, they defined them differently. Prien et al.

(15) illustrated this problem in a review of 78 studies describing the course of depression. They identified 28 different terms that were used to describe treatment outcome in these studies, and if modifiers of these terms, such as complete, full, and partial, were included, the number of terms increased to 64. The terms remission and recovery were sometimes used interchangeably, and their definitions varied from the attainment of a low score on a cross-sectional symptom severity scale covering the week before the evaluation to the complete to near-complete absence of the symptom criteria of major depressive disorder for at least 2 months. Disparities in the definitions of these concepts made it difficult to assimilate and draw conclusions from the literature.

A consensus conference was held in 1988 to standardize the definitions of terms such as remission, relapse, and recurrence

(16). Full remission was defined as a relatively brief period during which the individual is asymptomatic. Asymptomatic was not defined as a complete absence of symptoms but instead was defined as no more than minimal symptoms. Asymptomatic was operationalized as a score of ≤7 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D).

In antidepressant efficacy trials remission is typically defined according to scores on symptom severity scales such as the HAM-D and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

(17). Normalization of functioning is often mentioned as an important component of the definition of remission

(18–

20), although it is rarely used in treatment studies to identify patients in remission. Other constructs that seem relevant to determining whether a patient’s depressive episode is in remission include the ability to cope with stress, a sense of well-being, quality of life, and feeling like one’s normal self. We describe here results of a survey of the factors patients consider important in defining remission from depression.

Method

The study was conducted from August 2003 to July 2004. Participants were 535 psychiatric outpatients who were being treated for a DSM-IV major depressive episode in the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry outpatient practice. This private practice group predominantly treats individuals with medical insurance on a fee-for-service basis, and it is distinct from the hospital’s outpatient residency training clinic that predominantly serves lower-income patients who are uninsured and receiving medical assistance. The participants included 182 men (34.0%) and 353 women (66.0%) who ranged in age from 21 to 80 years (mean=44.2 years, SD=11.5). The Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Review Committee approved the research protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent.

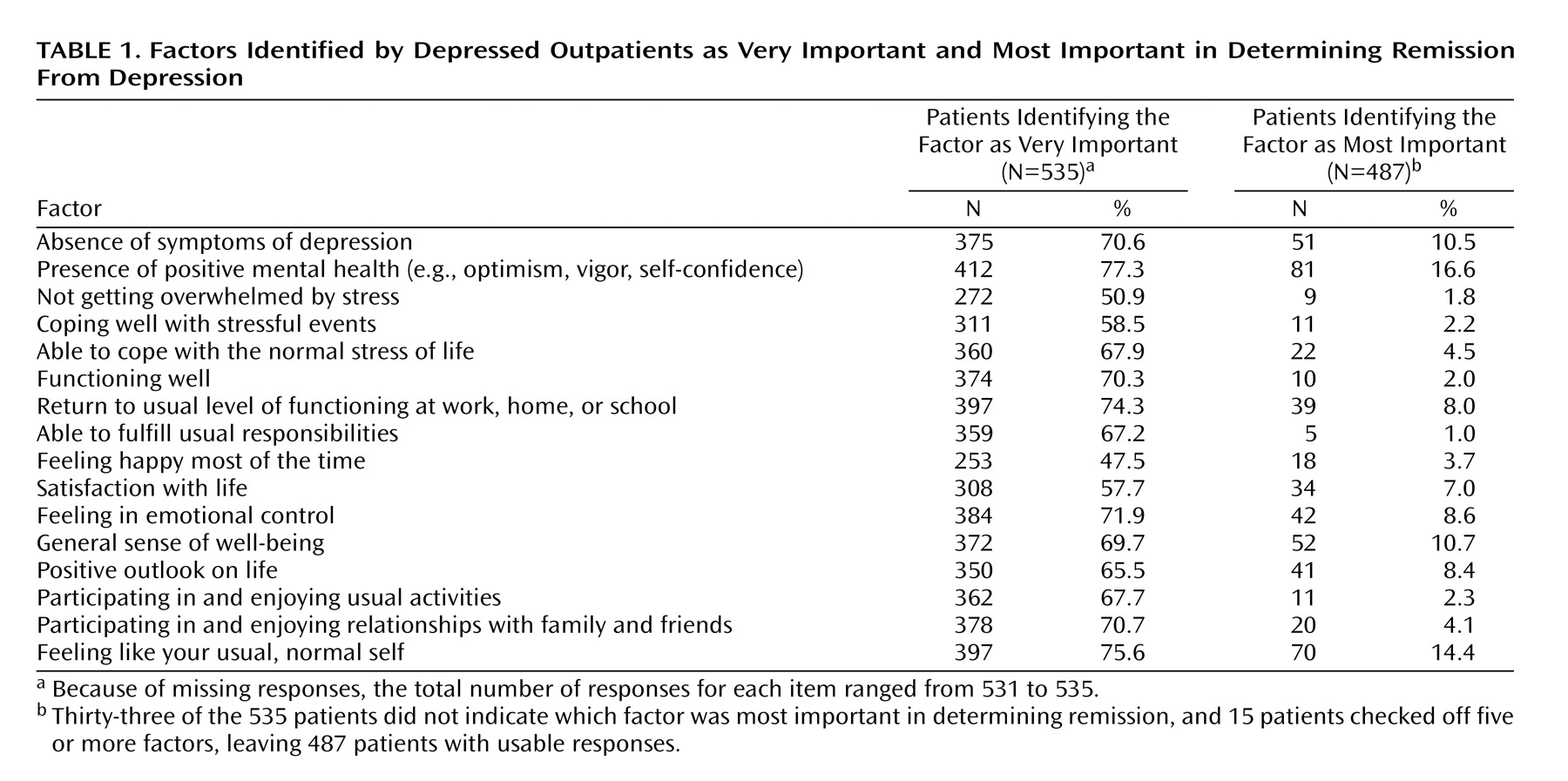

Before constructing the questionnaire we interviewed patients regarding their concepts of remission. Patients were asked how they knew that their depression was in remission, or, if they were still depressed, how they would know when their depression was in remission. From these unstructured interactions we derived a list of 16 potentially relevant factors (

Table 1).

The specific rating instructions were: “Using the following rating scale, please indicate how important you think each of the following factors is in determining whether someone is in remission from their depression: 0=not very important; 1=somewhat important; 2=very important in determining if someone is in remission from their depression.” After rating each item, the subject was asked to circle the number of the item that was judged to be the most important factor in determining whether someone’s depression is in remission. We decided a priori to combine the ratings of not very important and somewhat important.

Results

Most patients judged at least one of the 16 factors as very important in determining remission from depression (N=523 [97.7%]). On average, patients rated 10.7 factors (SD=4.0) as very important. Eighty-two patients (15.3%) rated all 16 factors as very important in determining remission from depression, and 15 of the 16 factors were considered very important by more than one-half of the patients (

Table 1). The three factors that were the most frequently judged to be very important in determining remission were the presence of features of positive mental health such as optimism and self-confidence; a return to one’s usual, normal self; and a return to usual level of functioning.

Thirty-three patients (6.2%) did not identify at least one of the factors as the most important in determining remission. Thirty-six (6.7%) chose two or more items. Of these 36 patients, we excluded the 15 patients who checked off five or more items as “the most important” factor in determining remission, thereby leaving a final sample of 487 respondents for this analysis.

Four items were selected by more than 10% of the patients as the most important factor in determining remission from depression: presence of positive mental health, a return to one’s usual self, a general sense of well-being, and the absence of symptoms of depression.

Discussion

Patients, their family members, treaters, third-party payers, employers, and even congressional committees are interested in the answer to the basic question of how many individuals improve when treated. Although there are many ways to define improvement, one endpoint of definite interest is the resolution, or remission, of the disorder. In the absence of biological markers of the disease state, remission from depression has been defined phenomenologically

(1). More specifically, remission has been defined in terms of the absence of symptoms on measures such as the HAM-D or MADRS. The results of the present study suggest that depressed patients consider symptom resolution as only one factor in determining the state of remission. In addition, patients indicated that the presence of positive features of mental health such as optimism, vigor, and self-confidence was a better indicator of remission than the absence of the symptoms of depression.

One of the principal goals of defining remission is to predict future morbidity. The basis for the recent emphasis on “treating to remission” is the consistent finding that treatment responders who meet the threshold for remission are significantly less likely to relapse than those who do not. Consequently, we recommend that studies comparing the respective validity of alternative conceptualizations of remission focus on prognosis.