Phobias run in families, and twin studies suggest that the modest familial aggregation observed in general population samples is mainly due to genetic factors

(1) . Exactly what is inherited, though, is unclear. In particular, it is of interest to determine to what extent the familial vulnerability to phobias is indexed by basic personality traits, such as extraversion and neuroticism

(2,

3) . Low extraversion (introversion) and high neuroticism enhance aversive conditioning in laboratory settings

(4 –

6) .

Extraversion and neuroticism are found in almost all personality nosologies

(7) . Extraversion refers to a person’s tendency to be venturesome, energetic, assertive, and sociable and to experience positive emotions (e.g., joy). Eysenck theorized that introverts have higher levels of activity in the ascending reticular activating system and are more “aroused” than extraverts, in that introverts are more distractible in high-stimulus environments and perform better at prolonged, monotonous tasks

(4) . Though the physical basis of extraversion remains under investigation

(6,

8), there is some empirical support for Eysenck’s theory

(4,

9) . Neuroticism refers to a person’s general tendency to experience negative emotions (e.g., nervousness, sadness, and anger). Eysenck theorized that neuroticism reflects a person’s characteristic limbic “excitability,” based on autonomic activation patterns

(4) .

Extraversion and neuroticism are moderately heritable

(12) and may contribute part of the heritable basis of phobias. A number of family studies have partially and indirectly addressed this hypothesis for social phobia. For example, trait anxiety, harm avoidance, and behavioral inhibition all combine aspects of introversion and neuroticism

(5,

13,

14) and appear familially related to social phobia

(15,

16) . To our knowledge, familial relationships between personality traits and agoraphobia have received less attention; however, agoraphobia appears familially related to behavioral inhibition

(17) . In contrast, behavioral inhibition does not appear familially related to specific phobias

(16) ; this finding is consistent with weak phenotypic relationships between personality traits and specific phobias.

Thus, extant family studies suggest that introversion and neuroticism may index the heritable liability to social phobia and agoraphobia, but they do not address whether the familial relationships are due to genetic or shared environmental factors (e.g., children could “learn” shy behavior from their social phobic or agoraphobic parents). Furthermore, none of the studies have tested whether there are independent contributions of introversion and neuroticism, since they all used measures that combine the two dimensions. Finally, to our knowledge, no studies have assessed whether there are inherited characteristics that are specific to phobias, beyond those indexed by personality traits.

In the current study, we employed large twin samples to address these issues for social phobia, agoraphobia, and a common specific phobia, animal phobia. On the basis of extant phenotypic and family studies, we predicted that both introversion and neuroticism would substantially index the genetic vulnerability to social phobia and agoraphobia. Also on the basis of extant studies, we expected that the results for animal phobia would contrast with those for social phobia and agoraphobia, in having weaker phenotypic and genetic relationships to personality traits.

Results

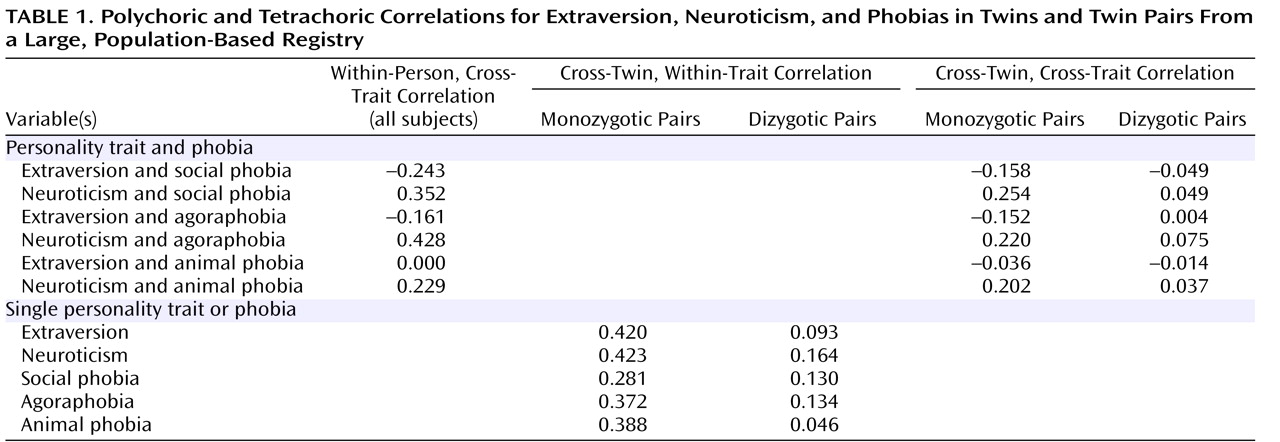

Table 1 shows polychoric and tetrachoric correlations for extraversion, neuroticism, and phobias in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. First, note the substantial negative within-person correlation between extraversion and social phobia and the positive within-person correlation between neuroticism and social phobia. These phenotypic correlations are consistent with prior observations; i.e., persons with social phobia are typically low in extraversion and/or high in neuroticism. Next, note that cross-twin correlations between extraversion and social phobia and between neuroticism and social phobia are larger in absolute value in monozygotic versus dizygotic twins; this suggests that genetic factors that affect extraversion and those that affect neuroticism also affect social phobia.

For agoraphobia, the pattern is similar to that for social phobia. In contrast, animal phobia was not at all phenotypically related to extraversion, and it was relatively weakly related to neuroticism. The genetic factors that influence animal phobia appear to overlap with those that influence neuroticism.

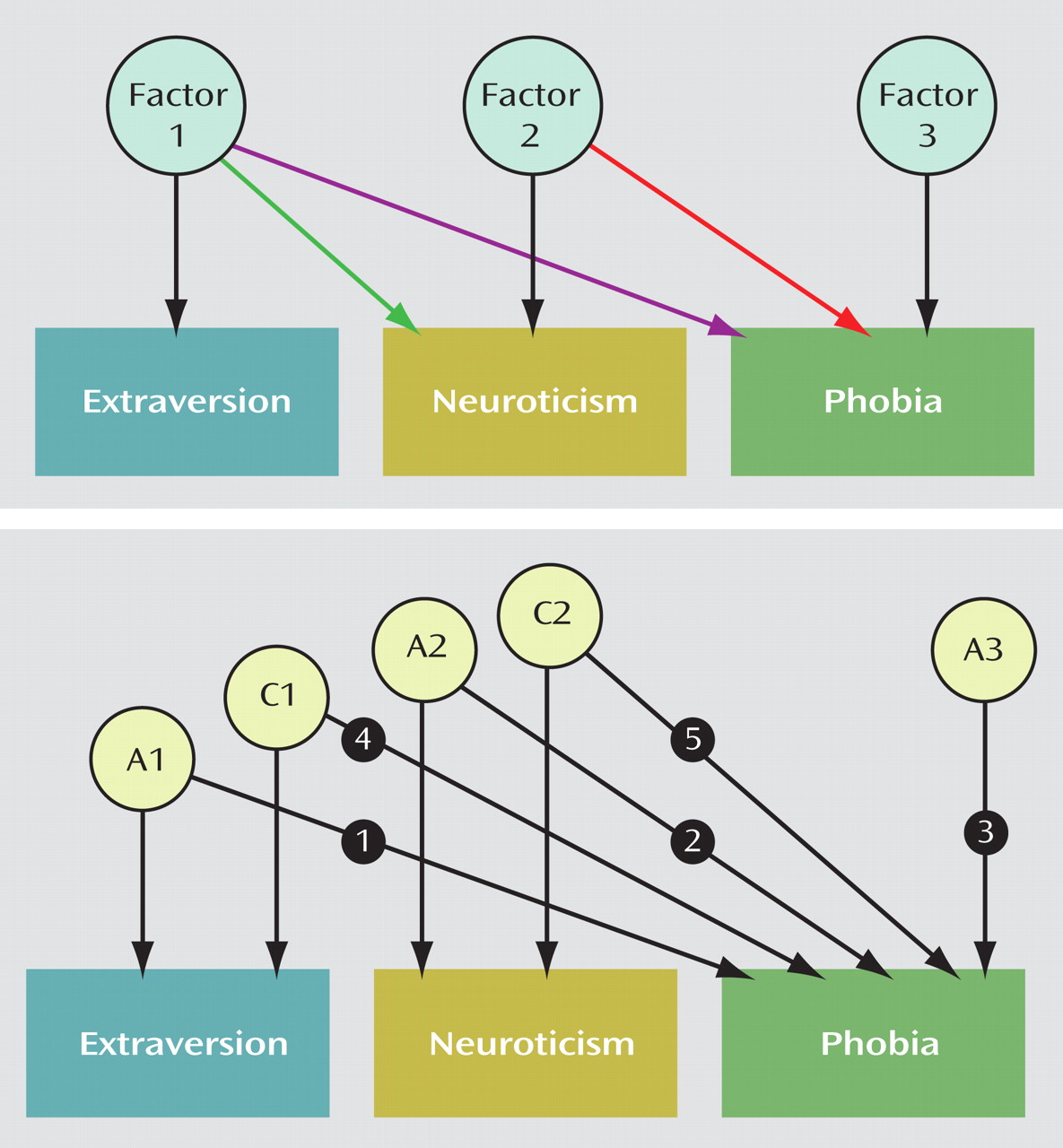

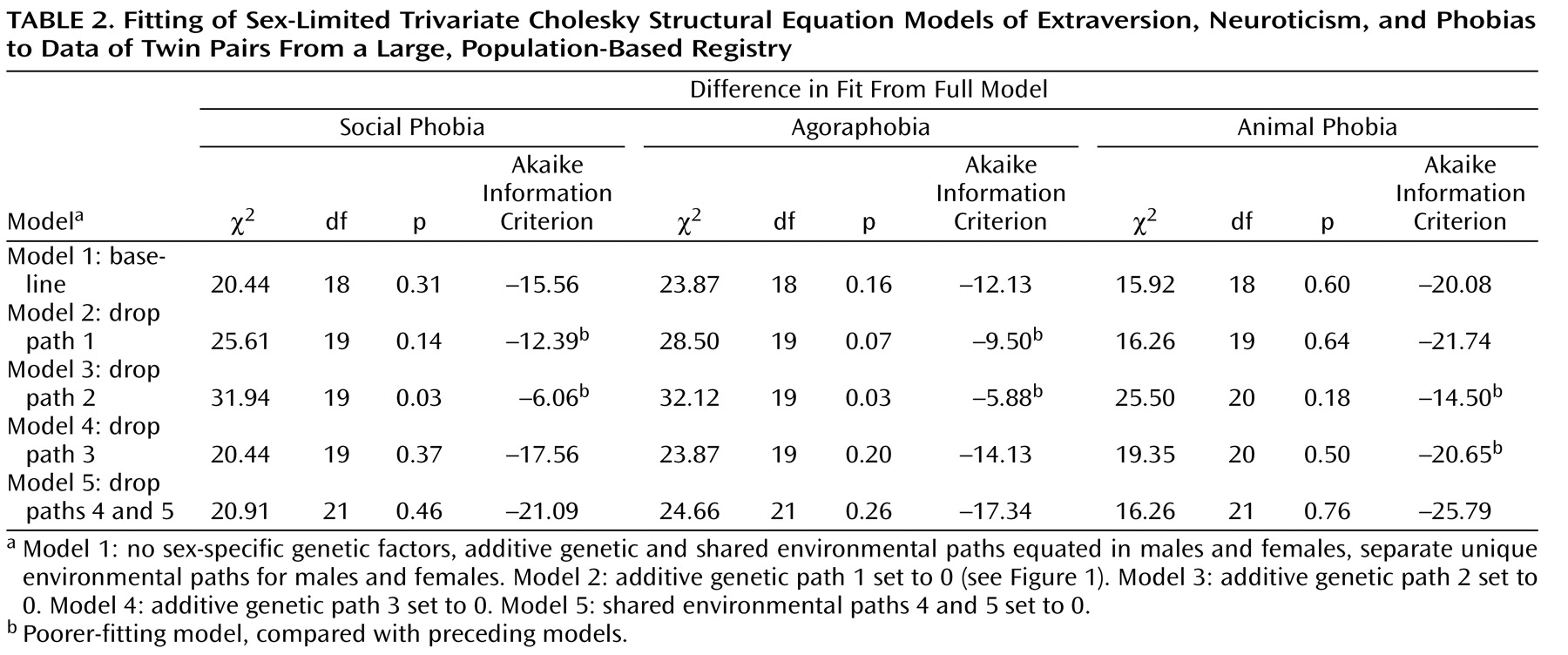

Table 2 shows the results of our model-fitting procedures (again, separate for each phobia). Model 1, our “baseline” model, includes the sex limitation of the unique environmental parameters specified earlier. In model 2, we set the additive genetic paths between extraversion and each phobia (path 1 in the lower part of

Figure 1 ) to zero. For the social phobia and agoraphobia models, this change resulted in a substantial loss of fit (higher AIC values), indicating that extraversion and these phobias share a portion of genetic determinants. In contrast, the reduced model fit the animal phobia data well, suggesting that extraversion and animal phobia are genetically unrelated. In model 3, we set the additive genetic paths between neuroticism and each phobia (path 2 in

Figure 1 ) to zero, and there was substantial worsening of fit in every case. This indicates that neuroticism and all three phobias share a significant portion of genetic determinants, separate from those of extraversion. In model 4, we dropped the phobia-specific additive genetic paths (path 3 in

Figure 1 ), with a substantial improvement in fit for social phobia and agoraphobia but a worsening of fit for animal phobia. This suggests that the quantitative measures extraversion and neuroticism themselves fully index the genetic liability to social phobia and agoraphobia, but not animal phobia (i.e., there was evidence for substantial genetic factors specific to animal phobia). In model 5, we set the common environmental paths between extraversion and each phobia and between neuroticism and each phobia (paths 4 and 5 in

Figure 1 ) to zero. In each case, these changes produced further improvements in the AIC (lower values), suggesting that environmental experiences shared by twins contribute little to the covariation between these personality traits and phobias.

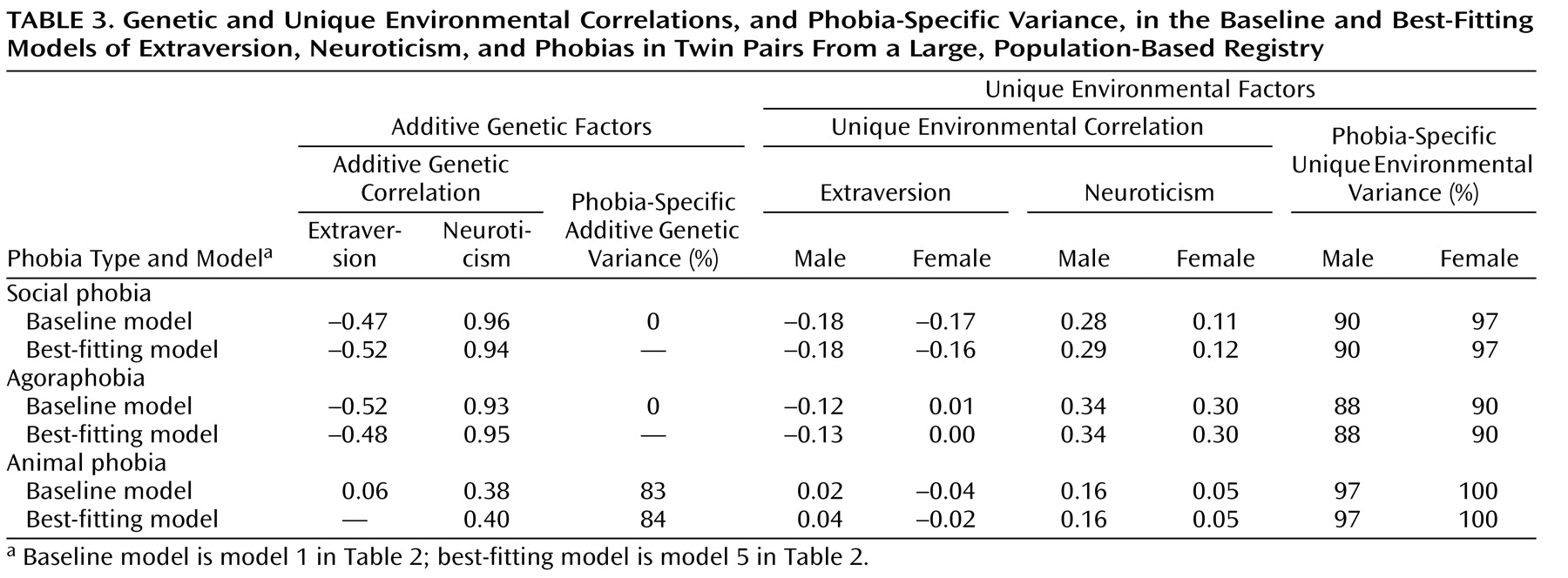

Table 3 shows results for each baseline model (model 1) and best-fitting model (model 5) in terms of additive genetic correlations (r

g values—estimates of the degree to which the same genetic factors influence two variables) and unique environmental correlations (r

e values—estimates of the degree to which the same environmental factors influence two variables), as well as the percentage of phobia-specific additive genetic and unique environmental variance, i.e., that not shared with extraversion or neuroticism. Shared environmental parameters are not shown, since the corresponding path coefficients were quite small. The baseline and best-fitting models were very similar. The estimates of r

g were substantial for the additive genetic correlations between extraversion and social phobia or agoraphobia (negative correlations) and between neuroticism and these phobias (positive correlations), while the r

e estimates were relatively small. The corresponding r

g values for animal phobia were considerably smaller than those for social phobia and agoraphobia. The estimate of social phobia-specific and agoraphobia-specific genetic variance was 0%, while the estimate of animal phobia-specific genetic variance was greater than 80%.

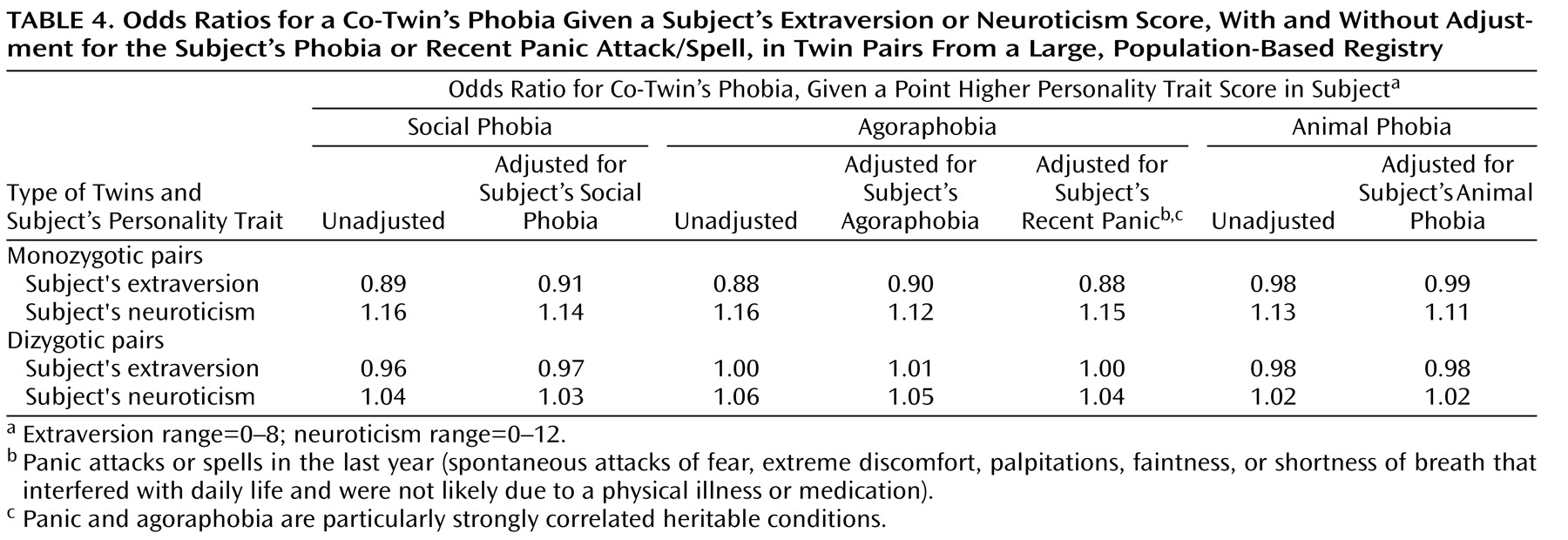

Since having a phobia or recent panic might affect personality measures

(27), we conducted logistic regression analyses to determine the extent to which a subject’s phobia or panic could confound the relationship between the subject’s personality traits and her or his co-twin’s phobia. As shown in

Table 4, accounting for a subject’s phobia or panic had little effect on these relationships (the odds ratios were comparable when a subject’s phobia or panic was taken into account). Note that these analyses likely overcontrol for psychopathology, since high neuroticism and behavioral inhibition appear to predict later onset of panic, social phobia, and perhaps agoraphobia

(14,

28,

29) .

Discussion

Our results suggest that the familial co-occurrence of certain personality traits and phobias has a genetic, not a shared environmental, basis. Further, genetic factors that influence individual variation in extraversion and neuroticism appear to account entirely for the genetic liability to social phobia and agoraphobia, but not animal phobia. Finally, our results indicate the importance of both introversion and neuroticism as personality endophenotypes for social phobia and agoraphobia. Though geneticists often seek a single basic dimension for an endophenotype, our results suggest that the greatest genetic risk for social phobia or agoraphobia involves genetic liability to both low extraversion and high neuroticism.

The extent to which introversion and neuroticism index the genetic vulnerability to social phobia and agoraphobia here is particularly noteworthy (estimated at 100%). For comparison, when we used this cohort and similar methods, estimates of the extent to which neuroticism indexes the genetic vulnerability to major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder were 36% (r

g =0.60), 59% (r

g =0.77), and 48% (r

g =0.69), respectively

(30) ; none of these conditions was associated with introversion

(31) . As expected, personality traits indexed only a small portion of the heritable basis of animal phobia in this study. The heritable basis of animal phobia may involve “preparedness” for aversive conditioning to specific stimuli

(32), which neither affects nor is affected by personality to a substantial degree.

In a previous multivariate twin study of neuroticism and internalizing disorders, we reported results for two broad genetic factors, one that influenced neuroticism and each disorder and a second, independent of neuroticism, that influenced major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder (the phobias did not have substantial loadings on this second factor)

(30) . The current study suggests that if a third genetic factor linked to extraversion were added to the earlier model, this third factor would account for the remaining genetic variance of social phobia and agoraphobia, though not animal phobia.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate genetic overlap between introversion and psychiatric disorders. Notably, the phenotypic and genetic correlations between extraversion and social phobia or agoraphobia were smaller in absolute value than those for neuroticism here. This contrasts with results from another general population study

(11) in which we used a different personality measure

(33) and psychiatrist diagnoses; in that study, these phobias were more strongly related to introversion than to neuroticism. Thus, had we used an alternative measure of extraversion in this study (e.g., one that explicitly includes positive emotionality), the genetic correlations with social phobia or agoraphobia might have been larger in absolute value.

Some have argued that combining introversion with neuroticism, as in trait anxiety

(5) or harm avoidance

(13), provides a more parsimonious construct to describe the presumed temperamental vulnerability to anxiety and depressive disorders. However, since introversion is not consistently associated with

all of these disorders

(10,

11,

31), it seems useful to consider extraversion and neuroticism separately. It remains an open question whether the physical bases of neuroticism and introversion are most usefully construed as constituting a single neurobiological system

(5,

13) or two interacting systems

(4) .

Our results have obvious relevance for molecular genetics. As in other anxiety and depressive disorders, finding genes that influence neuroticism should be valuable in determining the etiology of phobias. Several groups are currently searching the genome for loci that influence neuroticism (for instance, see references

34 and

35 ). Our results suggest that determining the genetic basis of introversion/extraversion should also be valuable in determining the etiologies of social phobia and agoraphobia. We know of no current systematic studies to identify genetic loci that influence introversion/extraversion, though candidate gene studies exist for this phenotype (for instance, see reference

36 ). We hope that our findings stimulate further genetic research on extraversion.

While considering the implications of our study for clinical practice, prevention, and research, the limitations of our cross-sectional method should be borne in mind. That is, though our statistical model specifies that latent factors affect all of the phenotypes of interest directly (i.e., there are no causal arrows between the measured variables), it is conceivable that this is not the case. For example, it is possible that genetic and unique environmental factors affect personality traits directly and that introversion and/or neuroticism are themselves true risk factors for social phobia or agoraphobia. This would be consistent with theories regarding the effects of introversion and neuroticism on aversive conditioning (e.g., in the context of social evaluation; noisy, close, or exposed environments; and/or anxiety or panic symptoms)

(4,

5) and with theories that relate extraversion to reward-seeking behavior

(5) (i.e., extraverts should find venturing into unfamiliar or bustling public environments pleasurable). However, the hypothesis that personality traits mediate genetic risk for phobias and alternatives (e.g., personality traits are simply markers of genetic risk for social phobia or agoraphobia) are difficult to test with cross-sectional data when patterns of inheritance are similar across phenotypes, as in the current study

(25) ; a longitudinal study would be more appropriate (for instance, see reference

37 ). The results in

Table 4 suggest that “scar” and/or state effects could not account for much of the observed covariance in this study; nevertheless, a conservative conclusion is that low extraversion and high neuroticism are powerful indices of genetic risk for social phobia and agoraphobia in

adults .

Second, our models require several assumptions

(25), including the absence of assortative mating (likely minimal for the phenotypes considered here [

12,

38 ]) and the independence and additivity of the latent variables. Gene-environment interaction could affect twin similarity in either direction, depending on whether both twins are exposed to the specific environmental factor in question; to our knowledge, gene-environment interactions and correlations have yet to be demonstrated for the phenotypes studied here. It is important that the assumption of equal relevant shared environmental experiences for monozygotic and dizygotic twins appears valid here

(22,

23,

39) .

Third, though nonadditive genetic effects have been detected for personality traits

(12), we did not model these here. Given the inclusion of binary phenotypes (phobias), we had inadequate power to discriminate nonadditive from additive genetic effects.

Fourth, unique environmental effects and measurement error are confounded in our models; this may bias our unique environmental correlation estimates downward. Nevertheless, our low unique environmental correlations for personality traits and phobias parallel the low unique environmental correlation for avoidant personality traits and social phobia in the study by Reichborn-Kjennerud et al. that appears elsewhere in this issue of the Journal. In both studies, unique environmental experiences mainly seem to account for phenotypic differences in persons with similar genetic vulnerabilities.

Fifth, our samples were made up entirely of Caucasian twins born in Virginia. Thus, our results may not generalize to individuals from other backgrounds.