The co-occurrence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and psychoactive substance use disorder (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence) has been reported in a variety of clinical and research settings

(1 –

3) . Follow-up studies have documented a higher than expected risk for psychoactive substance use disorder in adults who had ADHD as children

(4,

5) . Studies of referred and nonreferred adults with ADHD have also documented a high risk for psychoactive substance use disorder

(6,

7) . Most recently, Kessler and colleagues

(8) reported results from the National Comorbidity Survey indicating that adults with ADHD were at significantly higher risk for any substance use disorder and particularly drug dependence compared to respondents without ADHD.

Despite the contribution of this literature suggesting a familial association between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorder, several uncertainties remain. Many studies did not specifically examine the diagnosis of ADHD, did not use contemporaneous diagnostic criteria, did not adequately attend to the heterogeneity of psychoactive substance use disorder, and did not attempt to disentangle the type of familial association that may be operant between psychoactive substance use disorder and its subtypes with ADHD.

To this end, we reexamined patterns of familial association between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorder in the same group that we previously studied in adolescence

(19) at the 10-year follow-up into young adult years with added attention to subtypes of psychoactive substance use disorder. We conducted familial risk analyses based on models proposed by Pauls et al.

(20), testing hypotheses about the familial relationship between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorder. Specifically, we tested three competing hypotheses: 1) ADHD and addiction to drugs and alcohol are etiologically independent, 2) ADHD and addiction to drugs and alcohol represent a distinct familial subtype, and 3) ADHD and addiction to drugs and alcohol share common familial etiologic factors (variable expressivity hypothesis).

Results

Demographic Characteristics

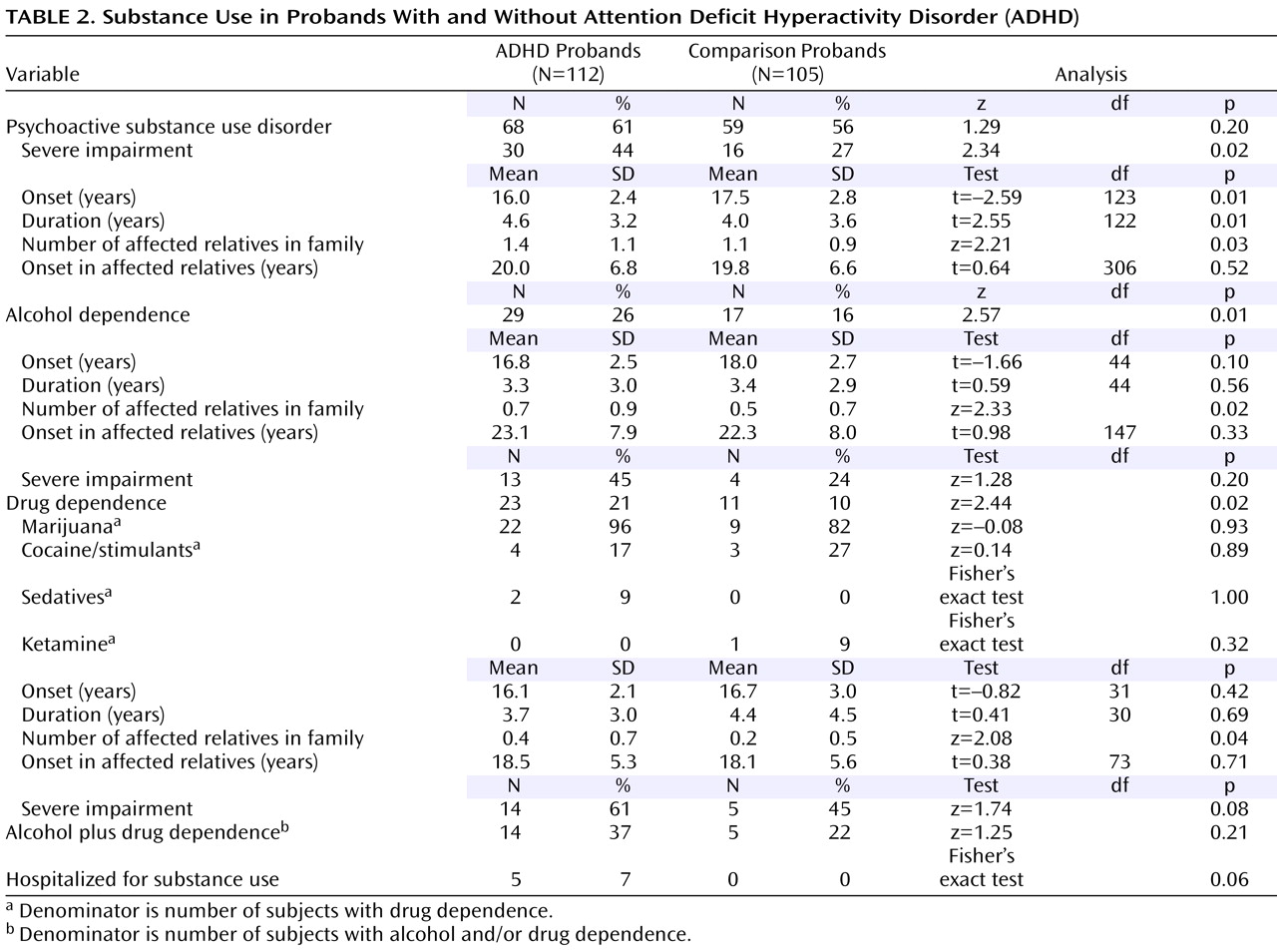

Because probands with ADHD were significantly younger than comparison probands, proband age was controlled for in all analyses (

Table 1 ). Details on attrition are provided in a previous publication

(22) .

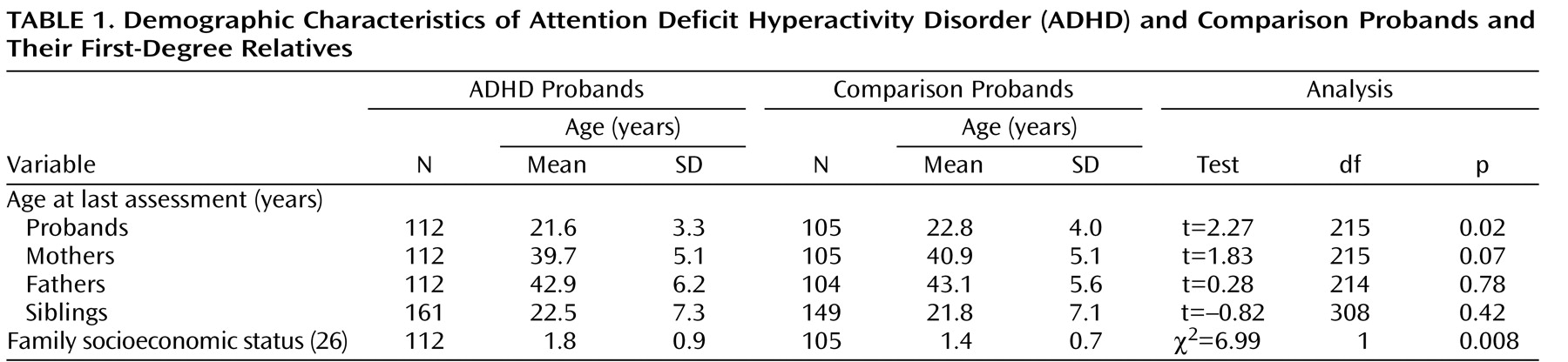

Characteristics of Substance Use in ADHD and Comparison Probands

Rates of psychoactive substance use disorder (alcohol abuse, drug abuse, alcohol dependence, or drug dependence) did not differ between ADHD and comparison probands, but ADHD probands had a significantly earlier onset, a longer duration, higher rates of severe impairment associated with psychoactive substance use disorder, and more affected first-degree relatives in relation to comparison probands (

Table 2 ). Rates of both alcohol and drug dependence were significantly higher in the ADHD probands than in the comparison probands, as well as the number of first-degree relatives affected with the same disorder.

Familial Risk for ADHD and Psychoactive Substance Use Disorder

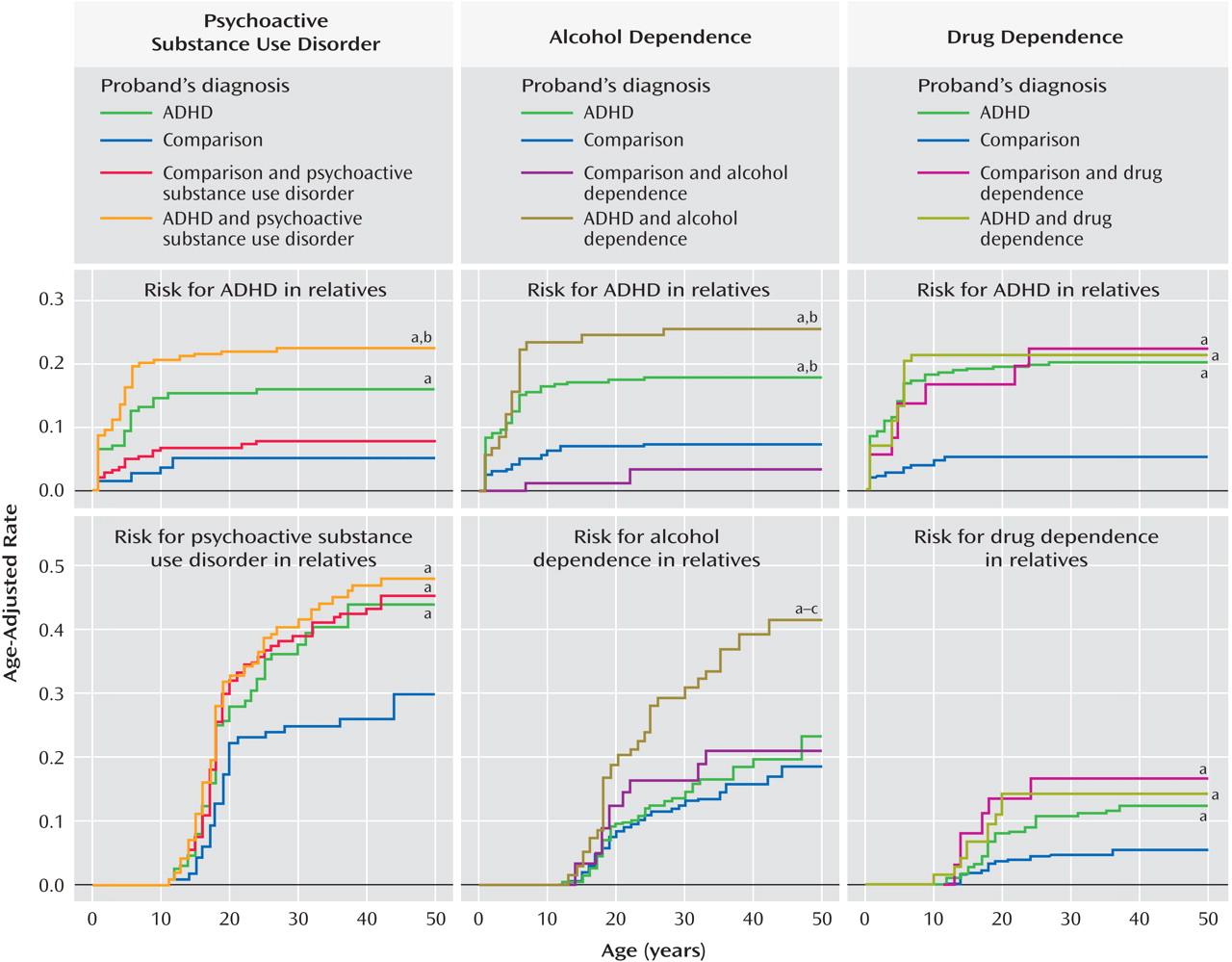

Four groups were used for the familial risk analysis of psychoactive substance use disorder and ADHD: the relatives of 46 comparison probands without psychoactive substance use disorder (comparison probands, N=153), the relatives of 59 comparison probands with psychoactive substance use disorder (comparison probands plus psychoactive substance use disorder, N=205), the relatives of 44 ADHD probands without psychoactive substance use disorder (ADHD, N=149), and the relatives of 68 ADHD probands with psychoactive substance use disorder (ADHD plus psychoactive substance use disorder, N=236).

Risk for ADHD in Relatives

Figure 1 (left) shows that age-adjusted rates of ADHD in the ADHD plus psychoactive substance use disorder and ADHD groups were significantly higher in relation to comparison probands (16% and 23% versus 5%; hazard ratio=1.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.3–2.1, p<0.001, and hazard ratio=1.8, CI=1.2–2.6, p=0.002, respectively). The ADHD plus psychoactive substance use disorder group also had significantly higher rates of ADHD in relation to the comparison probands plus the psychoactive substance use disorder group (23% versus 8%, hazard ratio=1.7, CI=1.2–2.5, p=0.004).

Risk for Psychoactive Substance Use Disorder in Relatives

The ADHD plus psychoactive substance use disorder, ADHD, and comparison probands plus psychoactive substance use disorder groups all had significantly higher age-adjusted rates of psychoactive substance use disorder in relation to the comparison probands (48%, 44%, and 45% versus 30%; hazard ratio=1.2, CI=1.1–1.4, p=0.001; hazard ratio=1.3, CI=1.0–1.7, p=0.02; and hazard ratio=1.7, CI=1.1–2.7, p=0.02, respectively;

Figure 1, left). There was no evidence for cosegregation in the ADHD plus psychoactive substance use disorder group (68% psychoactive substance use disorder in subjects with ADHD versus 48% psychoactive substance use disorder in subjects without ADHD, p=0.08).

Familial Risk for ADHD and Alcohol Dependence

The familial risk analysis of alcohol dependence and ADHD used four groups: the relatives of 88 comparison probands without alcohol dependence (comparison probands, N=294), the relatives of 17 comparison probands with alcohol dependence (comparison probands plus alcohol dependence, N=64), the relatives of 83 ADHD probands without alcohol dependence (ADHD, N=283), and the relatives of 29 ADHD probands with alcohol dependence (ADHD plus alcohol dependence, N=102).

Risk for ADHD in Relatives

Figure 1, middle, shows that the rates of ADHD in the ADHD plus alcohol dependence and ADHD groups were significantly higher in relation to comparison probands (18% and 26% versus 8%; hazard ratio=1.6, CI=1.2–2.0, p<0.001, and hazard ratio=1.6, CI=1.2–2.1, p=0.001, respectively) and comparison probands plus alcohol dependence (18% and 26% versus 4%; hazard ratio=3.1, CI=1.5–6.3, p=0.002, and hazard ratio=6.6, CI=1.7–25.0, p=0.006, respectively).

Risk for Alcohol Dependence in Relatives

The ADHD plus alcohol dependence group had a significantly higher age-adjusted rate of alcohol dependence in relatives in relation to comparison probands (42% versus 18%; hazard ratio=1.4, CI=1.2–1.6, p<0.001), comparison probands plus alcohol dependence (42% versus 21%; hazard ratio=1.5, CI=1.0–2.2, p=0.05), and ADHD groups (42% versus 23%; hazard ratio=2.4, CI=1.4–4.0, p=0.002;

Figure 1, middle). There was no evidence for cosegregation in the ADHD plus alcohol dependence group (46% alcohol dependence in probands with ADHD versus 40% alcohol dependence in probands without ADHD, p=0.08).

Familial Risk for ADHD and Drug Dependence

The familial risk analysis of drug dependence and ADHD used four groups: the relatives of 94 comparison probands without drug dependence (comparison probands, N=321), the relatives of 11 comparison probands with drug dependence (comparison probands plus drug dependence, N=37), the relatives of 89 ADHD probands without drug dependence (ADHD probands, N=309), and the relatives of 23 ADHD probands with drug dependence (ADHD probands plus drug dependence, N=76).

Risk for ADHD in Relatives

Figure 1 (right) shows that the rates of ADHD in the ADHD plus drug dependence, ADHD, and comparison probands plus drug dependence groups were significantly higher in relation to the comparison probands (21%, 20%, and 22% versus 5%; hazard ratio=1.7, CI=1.3–2.2, p<0.001; hazard ratio=2.1, CI=1.5–2.7, p<0.001; and hazard ratio=8.0, CI=2.6–24.9, p<0.001, respectively).

Risk for Drug Dependence in Relatives

Likewise,

Figure 1 (right) shows that the rates of drug dependence were significantly higher in the ADHD plus drug dependence, ADHD, and comparison probands plus drug dependence groups in relation to comparison probands (14%, 12%, and 17% versus 5%; hazard ratio=1.4, CI=1.1–2.0, p=0.02; hazard ratio=1.5, CI=1.0–2.3, p=0.04; and hazard ratio=5.0, CI=1.2–21.0, p=0.03, respectively). There was no evidence for cosegregation in the ADHD plus drug dependence group (21% drug dependence in subjects with ADHD versus 12% drug dependence in subjects without ADHD, p=0.34).

Nonrandom Rating Among Parents

There was no evidence for nonrandom mating of parental ADHD and parental psychoactive substance use disorder, alcohol dependence, or drug dependence (all p>0.15).

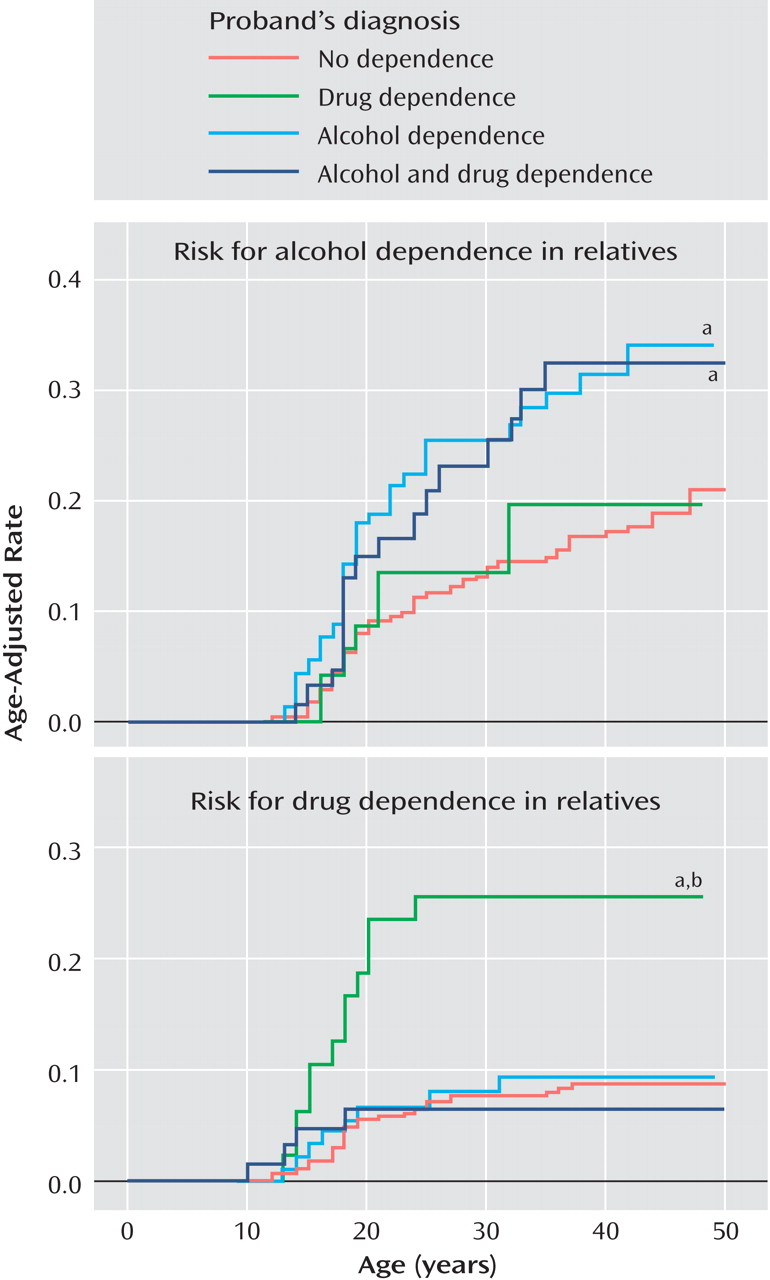

Specific Versus Common Risk for Dependence

The following four groups were used: the relatives of 156 probands without alcohol dependence and without drug dependence (no dependence, N=528), the relatives of 27 probands with alcohol dependence but without drug dependence (alcohol dependence, N=102), the relatives of 15 probands with drug dependence but without alcohol dependence (drug dependence, N=49), and the relatives of 19 probands with alcohol and drug dependence (alcohol plus drug dependence, N=64).

Risk for Alcohol Dependence in Relatives

Figure 2 (top) shows that the alcohol dependence and alcohol plus drug dependence groups had significantly higher rates of alcohol dependence compared to the no dependence group (34% and 32% versus 21%; hazard ratio=2.1, CI=1.2–3.7, p=0.009, and hazard ratio=1.2, CI=1.0–1.5, p=0.02, respectively).

Risk for Drug Dependence in Relatives

Figure 2 (top) shows that the drug dependence group had a significantly higher rate of drug dependence compared to the no dependence (26% versus 9%; hazard ratio=1.9, CI=1.4–2.7, p<0.001) and alcohol dependence (26% versus 10%; hazard ratio=3.0, CI=1.3–6.9, p=0.01) groups. These associations did not vary significantly by the ADHD status of the proband (both interaction effects, p>0.05).

Effect of Mood Disorders on Risk for Substance Use

A secondary analysis was conducted to determine if the risk for alcohol and drug dependence was mediated by mood disorders. Independent of proband ADHD and alcohol dependence status, neither proband major depression with severe impairment (p=0.25) nor proband bipolar disorder (p=0.09) significantly added to the risk for alcohol dependence in relatives. Independent of proband ADHD and drug dependence status, proband major depression with severe impairment did not significantly predict drug dependence in the relatives (p=0.26), but proband bipolar disorder significantly added to the risk for drug dependence in the relatives (hazard ratio=3.4, CI=1.7–7.0, p=0.001).

Discussion

In a systematic evaluation of the familial relationship between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorder with a well-characterized longitudinal group of ADHD boys as adults and their first-degree relatives, we found the following:

ADHD in the proband was consistently associated with a significantly increased risk for ADHD in relatives irrespective of comorbidity with psychoactive substance use disorder

ADHD in the proband also predicted psychoactive substance use disorder and drug dependence in the relatives

Drug dependence in comparison probands increased the risk for ADHD in relatives

Alcohol dependence in relatives was predicted only by ADHD probands with comorbid alcohol dependence

Both alcohol dependence and drug dependence bred true in families without evidence of a common risk between these disorders.

Although probands with and without ADHD did not differ on the absolute rates of the combined category of any psychoactive substance use disorder, probands with ADHD had an earlier onset, a longer duration, and higher rates of severely impairing psychoactive substance use disorder as well as higher rates of alcohol and drug dependence. Moreover, probands with ADHD had more first-degree relatives with psychoactive substance use disorder, alcohol, and drug dependence in relation to comparison probands. Taken together, these findings indicate that the type of psychoactive substance use disorder that develops in the context of ADHD is a very morbid form of the disorder and support the hypothesis that ADHD is a familial risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorder.

The rates of substance use in the relatives of comparison probands were consistent with the National Comorbidity Survey

(28) for psychoactive substance use disorder (32.1% versus 26.6%, respectively) and alcohol dependence (13.7% versus 14.1%, respectively). The relatives of comparison probands had a 5.6% prevalence of drug dependence, in between the 7.5% prevalence reported by the National Comorbidity Survey

(28) and the 2.6% prevalence recently reported by Compton and colleagues

(29) . For comparison probands, the rates of alcohol and drug dependence were consistent with the National Comorbidity Survey

(28), but the rate of the combined category of psychoactive substance use disorder was twice as high. Although the reasons for this high rate of psychoactive substance use disorder in comparison probands are not entirely clear, it was driven mainly by elevated rates of alcohol abuse that may reflect the high risk for binge drinking in young adults in this age range. For example, the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study

(30) found that 44% of college students were binge drinkers, which was the same percentage of our comparison probands with alcohol abuse (44%, 46 of 105).

ADHD in the proband consistently increased the risk for ADHD in relatives irrespective of psychoactive substance use disorder status. The finding that the risk for psychoactive substance use disorder in relatives was increased in ADHD probands with and without psychoactive substance use disorder is consistent with the variable expressivity hypothesis that ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorder share common risk factors.

Evaluation of the subtypes of psychoactive substance use disorder revealed divergent patterns of familial transmission for alcohol and drug dependence. Findings revealed that the risk for alcohol dependence was only elevated in the relatives of probands with comorbid ADHD plus alcohol dependence. These results, together with the absence of cosegregation and nonrandom mating between ADHD and alcohol dependence, fit best with the hypothesis of independent transmission between these disorders, with the caveat that the risk for alcohol dependence exists only in the context of families with alcohol dependence and ADHD. In the event that there had been cosegregation of ADHD and alcohol dependence, the findings would have better fit with the hypothesis of family subtype.

On the other hand, the risk for drug dependence was consistent with the variable expressivity hypothesis that the two disorders share common familial determinants. Specifically, the rates of ADHD were equally elevated in the relatives of probands with ADHD, drug dependence, or both and significantly higher than the rate of ADHD in comparison relatives. Likewise, the relatives of probands with ADHD, drug dependence, or both had significantly higher rates of drug dependence compared to the relatives of comparison probands but similar rates of drug dependence compared to each other. Common risks may involve dopamine genes

(31) that affect attention and arousal as well as the reward pathways associated with drug dependence. Due to our differential findings for alcohol and drug dependence, genetic studies of ADHD may benefit from understanding the biological and genetic differences between alcohol and drug dependence. Alternatively, ADHD and drug dependence may share a common environmental factor and have distinct genetic causes.

These results are also consistent with findings by our group

(32) showing that in relation to comparison probands, adult subjects with ADHD exhibited a greater risk for drug abuse or dependence (8% versus 27%) than for alcohol abuse or dependence (16% versus 31%). Mannuzza et al.

(5) also showed that children with ADHD as adults have a high risk for drug use disorders and not alcohol use disorders.

The rates of alcohol dependence and drug dependence were selectively higher in the relatives of probands with the same diagnosis. This finding suggests that the risk for alcohol and drug dependence in relatives is specific to the type of addiction afflicting the probands and is consistent with findings from Merikangas et al.

(33), Bierut et al.

(34), and Milberger et al.

(35), which argue for specific and independent risks for alcohol and drug dependence. However, Nurnberger and colleagues

(36) suggested that alcohol and drug dependence share common mechanisms within some families. Additional work using community samples may resolve these differences because discrepant findings could be due to unique aspects of clinically ascertained samples.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Despite significant differences between ADHD and comparison families in socioeconomic status, our analyses did not control for socioeconomic status. Although future studies should help elucidate the relationship between socioeconomic status, ADHD, and psychoactive substance use disorder, socioeconomic status may not be a true covariate because the outcome (substance use disorders) could affect the covariate (family socioeconomic status) on a majority of the units of analysis (parents).

Our secondary analysis further confirmed that alcohol dependence is independently transmitted because proband mood disorders did not affect the risk for alcohol dependence in the relatives. However, the same analysis suggested that the risk for drug dependence in the relatives could be accounted for by comorbid bipolar disorder in the probands. Future studies should assist in determining the precise nature of the variably expressed risk for drug dependence. In addition, because marijuana was the preponderant drug of dependence in the probands, our findings of variable expressivity may not generalize to other drugs.

Another potential source of bias stems from the indirect psychiatric assessments with the mothers about the probands and their siblings. This method may have led to an underrepresentation of psychopathology in the children. In addition, although the probands and their siblings were assessed at baseline and follow-up assessments, the parents were assessed only at baseline. Thus, it is possible that additional cases of substance use disorders emerged in the parents during the 10-year follow-up period, although the use of Cox models to calculate age-adjusted rates somewhat mitigates this concern. Our group was ascertained with DSM-III-R criteria, so the findings may have differed had DSM-IV been used. However, Biederman and colleagues

(37) showed that 93% of children with a DSM-III-R diagnosis also received a DSM-IV diagnosis. Finally, community-based studies should determine if these findings extend to the general population. Studies should also determine if samples of females with ADHD would yield consistent results.

In summary, in a group of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred children and adolescents with ADHD, familial risk analyses suggest that the association between ADHD and drug and alcohol dependence are substance specific, and they are most consistent with the hypothesis of variable expressivity for drug dependence and independent transmission for alcohol dependence.