Major depression is often a chronic and recurring illness that drains our patients and the clinicians caring for them. Remission, not just response, is an important clinical and research goal, but fewer than half of depressed patients experience remission during treatment with the first prescribed antidepressant, even when combined with other care

(1) . More and more evidence is accumulating that continuing the right medications for months rather than weeks offers the best chance of a robust response, full remission

(2), and decreased risk of ongoing disability. Unfortunately, attrition from treatment is very common, and it may be as high as 60%

(3) . This leads to prolonged patient suffering and continues to bedevil the most devoted clinicians. Identification of demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics associated with attrition could guide the development and timing of interventions designed to keep patients in treatment. Initial selection of medications most likely to help a given individual would avoid the trial and error so many of our patients endure. Both of these developments would relieve individual suffering and have a positive impact on a major public health problem

(4) .

Two articles in this issue of the

Journal offer hope for the problems of treatment attrition and/or nonresponse to a given initial medication. Both use data from the multicenter, large-sample, real-world treatment study of resistant nonpsychotic depression, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

(5) . This study of over 4,000 actual patients in primary care and psychiatry clinics allowed broad inclusion criteria and minimized exclusion criteria in order to recruit a sample broadly representative of depressed patients in the United States. Patients with comorbid medical and some comorbid psychiatric conditions were enrolled, as long as their clinicians thought outpatient care was appropriate. Patients with previous intolerable side effects from medications used in the study were excluded. An initial score of at least 14 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale was required.

The first article, by Warden and colleagues, analyzed baseline and treatment-related characteristics of 4,041 patients in Level 1 of STAR*D, a 12-week trial of citalopram, to determine whether any characteristics were associated with attrition. The patients were reflective of the U.S. census, with 76% Caucasian, 18% African American, 2% Asian, and 4% other races or multiracial. Of these, 13% were Hispanic. A clinical research coordinator following measurement-based care guidelines

(6) met with patients at regularly scheduled intervals and allowed flexible dose adjustments based on patient response, as measured by the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology

(7) and the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating

(8) . By the end of the 12-week trial, 26% of the patients dropped out.

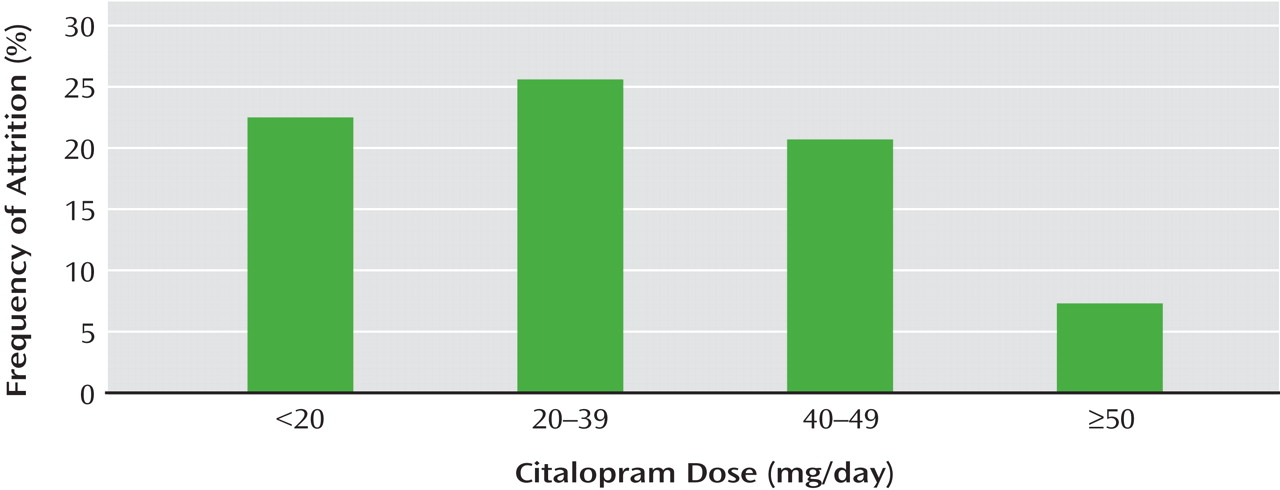

Several characteristics associated with patient dropout achieved statistical significance: African American race, younger age (37.8 versus 41.3 years), less education (12.6 versus 13.7 years), experience with more than one episode of depression, and for those who dropped out only after one visit, greater perceived mental health function. Other features associated with dropping out did not reach the strict statistical significance described in the report but showed clinically meaningful trends: Hispanic ethnicity, use of public insurance, a higher number of axis I psychiatric comorbidities, fewer years since the onset of depression, and greater severity of depressive symptoms at the time of dropping out. Compared to those who completed the study, those who dropped out also had lower levels of side effects and were prescribed lower doses of citalopram (

Figure 1 ). The authors recommend robust psychoeducational interventions and outreach focused on African American and Hispanic minority patients, those who are younger and those with less education, those with public insurance, and those who have had no or limited personal experiences of prolonged depression. These efforts could emphasize the benefits of treatment and the consequences of inadequate treatment. Particular attention could be given to assess individual barriers to treatment.

In the article by Warden et al., it is worth noting that some of the statistically significant differentiating demographic characteristics have little clinical or practical difference, such as a difference of 3.5 years of age or 1.1 years of education in adults who dropped out compared with those who completed the study. In contrast, the differences in symptom severity between those who dropped out and those who continued treatment have real and practical implications, especially since the ones who dropped out were also receiving lower doses of citalopram. Patients not experiencing satisfactory response early in treatment deserve aggressive psychoeducational/psychotherapeutic intervention and should be considered for earlier and increased dosage adjustments, balancing the risk of side effects, of course. Switch and augmentation strategies are discussed in other STAR*D reports and are not described in this article. As recommended in this report, the use of simple symptom scales in routine clinical care could also engage the patient in his or her treatment, help guide clinical decisions, and possibly decrease attrition. A patient who is measuring symptoms with his or her doctor is simultaneously learning about the disease and becoming an active partner in its treatment.

Although STAR*D is a real-world trial, there are some limitations to the generalizability of these results. Patients in this trial, even ones without insurance, had intensive interventions and attention not currently part of routine care in the United States. The study design excluded patients who had experienced severe side effects from citalopram, which precluded the opportunity to study the effect of side effects on continuation of treatment. In addition, the absence of a placebo group does not allow one to assess the interaction of time and medication. Some patients might have improved with the passage of time alone, although their history of treatment resistance makes this less likely.

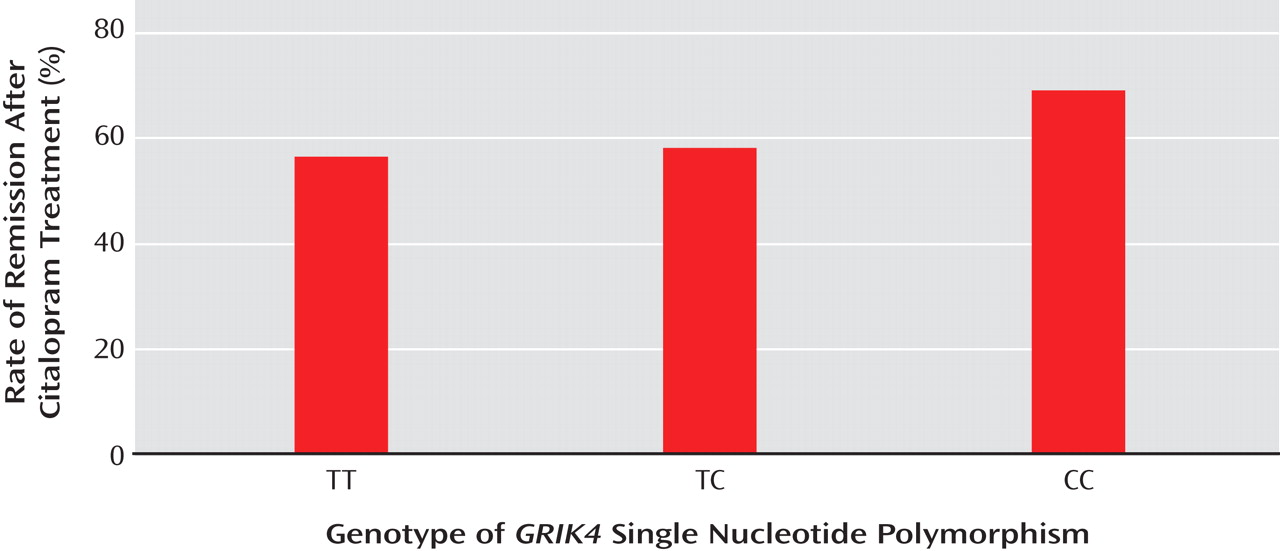

In the second article, by Paddock and colleagues, genetic samples from 1,816 depressed patients in the same STAR*D trial were analyzed to determine any associations between specific gene sites and response to citalopram. Associations with citalopram response were found with two genetic markers: a previously identified polymorphism in the serotonin 2A receptor gene,

HTR2A, and a newly identified marker in the gene

GRIK4, which codes for a kainic-acid type glutamate receptor. Although the authors acknowledge modest effect sizes, patients’ genotypes at one of the single nucleotide polymorphisms in

GRIK4 were significantly associated with achieving or failing to achieve remission (

Figure 2 ). Genotypes at

HTR2A had already been shown to affect response similarly, and the effects of the two genes appear to be additive

(9) . These results suggest a role for glutamate as well as for serotonin in modulating the response to at least one selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, citalopram. They also raise the exciting possibility of pretreatment identification of patients more or less likely to experience response to a given medication.

Taken together, the results of these two studies offer hope to patients with nonpsychotic major depression. The effect sizes of all measures are modest, but these reports represent a good start. The Warden et al. study gives us clinical applications we can use now, including ones of minimal cost. The one by Paddock et al., while not immediately usable by clinicians, hints at the eventual benefit promised by a more and more specific understanding of the function of the genes identified in the human genome project. Building on the work of Paddock et al., future studies of genes related to depression could help us understand other relevant antidepressant mechanisms, guide antidepressant selection, and eventually lead to a more refined understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of depression itself

(10) .

Currently, many antidepressants are prescribed to our patients, but in only a tiny percentage of cases are the medications and any integrated psychosocial treatment

(11,

12) given long enough to achieve clear remission. Patients are faced with the unavoidable curse of a trial-and-error approach in which various medications are started and stopped with almost no opportunity for individualized medication selection and little opportunity to develop psychoeducational strategies tailored to specific demographic or clinical groups. If studies such as the two in this month’s

Journal are replicated and extended, clinicians could one day be guided by a combination of genetic analysis and demographic, clinical, and treatment factors to select and deliver truly individualized care, including a medication most likely to be effective, in the context of a therapeutic alliance between the patient and the treatment team. This approach could combat discouragement, increase the likelihood of the patient remaining in treatment, and lead to real remission.

In addition to the specific benefit of these two STAR*D-based reports, which increase our understanding of factors affecting response rates in nonpsychotic depression, it is worth noting the more general benefits STAR*D is bringing to patients and clinicians. A first round of primary outcome reports has been published, and now investigators are able to look at more fine-grained analysis of the data, as exemplified in these two articles related to predictors of nonresponse. NIMH’s investment of resources into these large, real-world studies is providing real clinicians and patients some initial answers not provided by smaller studies, including industry-funded ones. This brings real help and hope to us all.