Since the initial report by Chumakov et al.

(1) of an association between markers at the

G72 locus and schizophrenia in samples from Russia and Canada and subsequent reports by Hattori et al.

(2), Chen et al.

(3), and Schumacher et al.

(4) showing association between this locus and bipolar disorder in samples from the United States and Germany, this locus has become the focus of increased attention in psychiatric genetic research. A recent meta-analysis by Detera-Wadleigh and McMahon

(5) concluded that the association findings between

G72 and both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are “among the most compelling in psychiatry” despite the fact that associated alleles and haplotypes are not identical across studies and functional variants remain to be demonstrated. Findings are not limited to a specific population, being observed in European, North American, Han Chinese, and Ashkenazi samples, with few studies reporting nonassociations

(5 –

9) . Our group reported association of identical

G72 haplotypes with both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in the German population

(4) . In line with findings from other groups on

G72, our findings support the notion of a genetic overlap across major psychiatric diagnoses. Such a genetic overlap has also been suggested by studies of

DTNBP1 (dysbindin),

COMT, BDNF, DISC1, and

NRG1 (10 –

17) .

Although there is now increasing support for the

G72 locus as a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

(15 –

18) as well as evidence for an etiological role in panic disorder

(19), a potential association with major depression still needs to be assessed, in particular given the well-established familial clustering of major depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders

(20 –

22) . Moreover, a large multicenter study provided evidence of linkage between major depression and a locus on 13q31.1–q31.3 (76.1–92.6 megabases on National Center for Biotechnology Information build 35), thus lying in the vicinity of

G72 (104.9 megabases on National Center for Biotechnology Information build 35; reference

23 ).

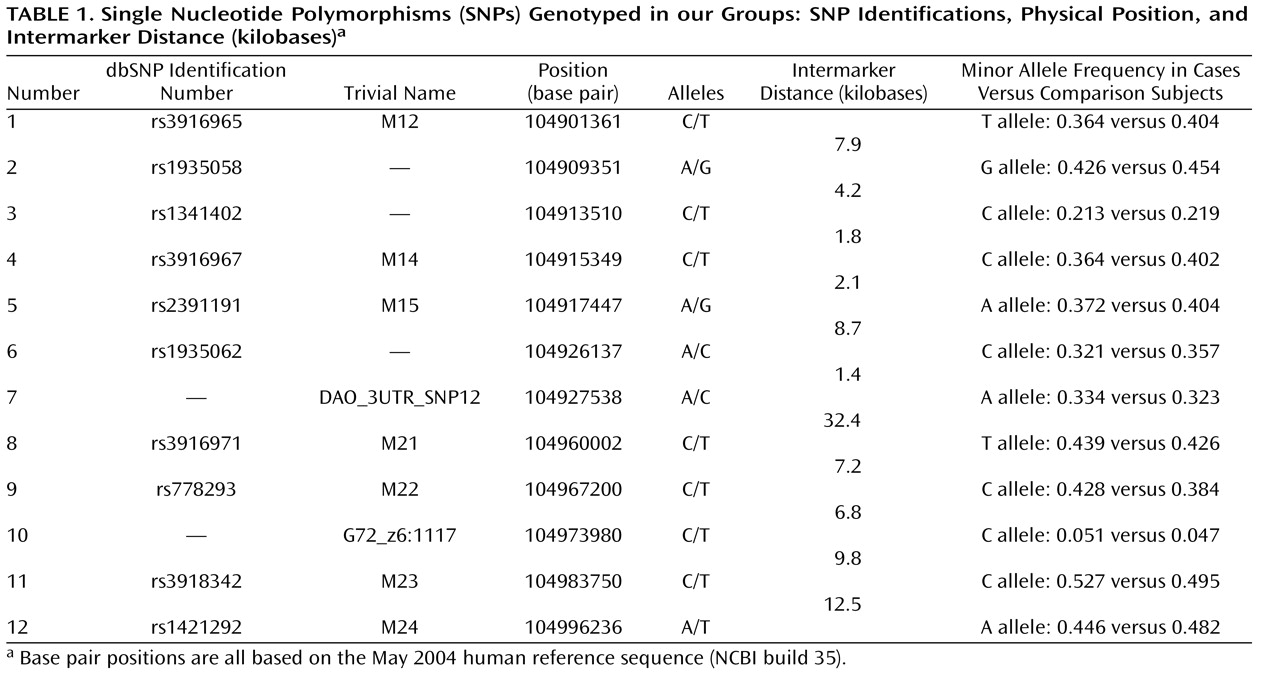

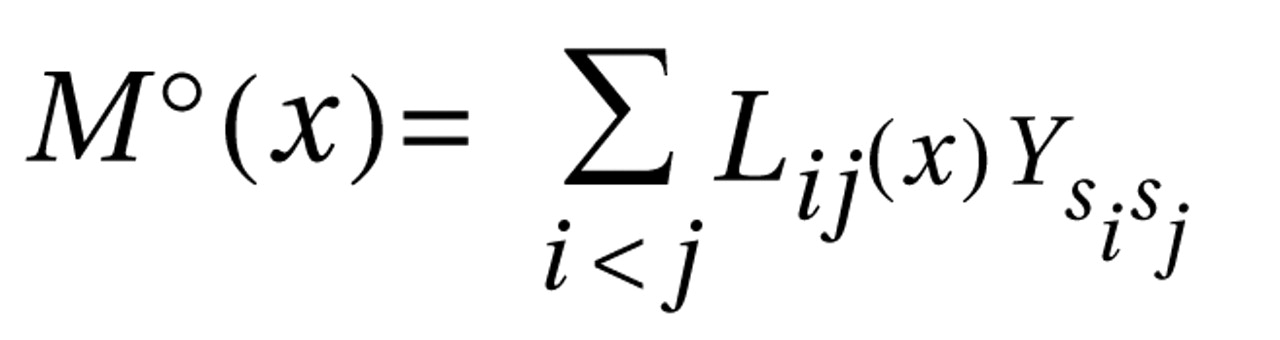

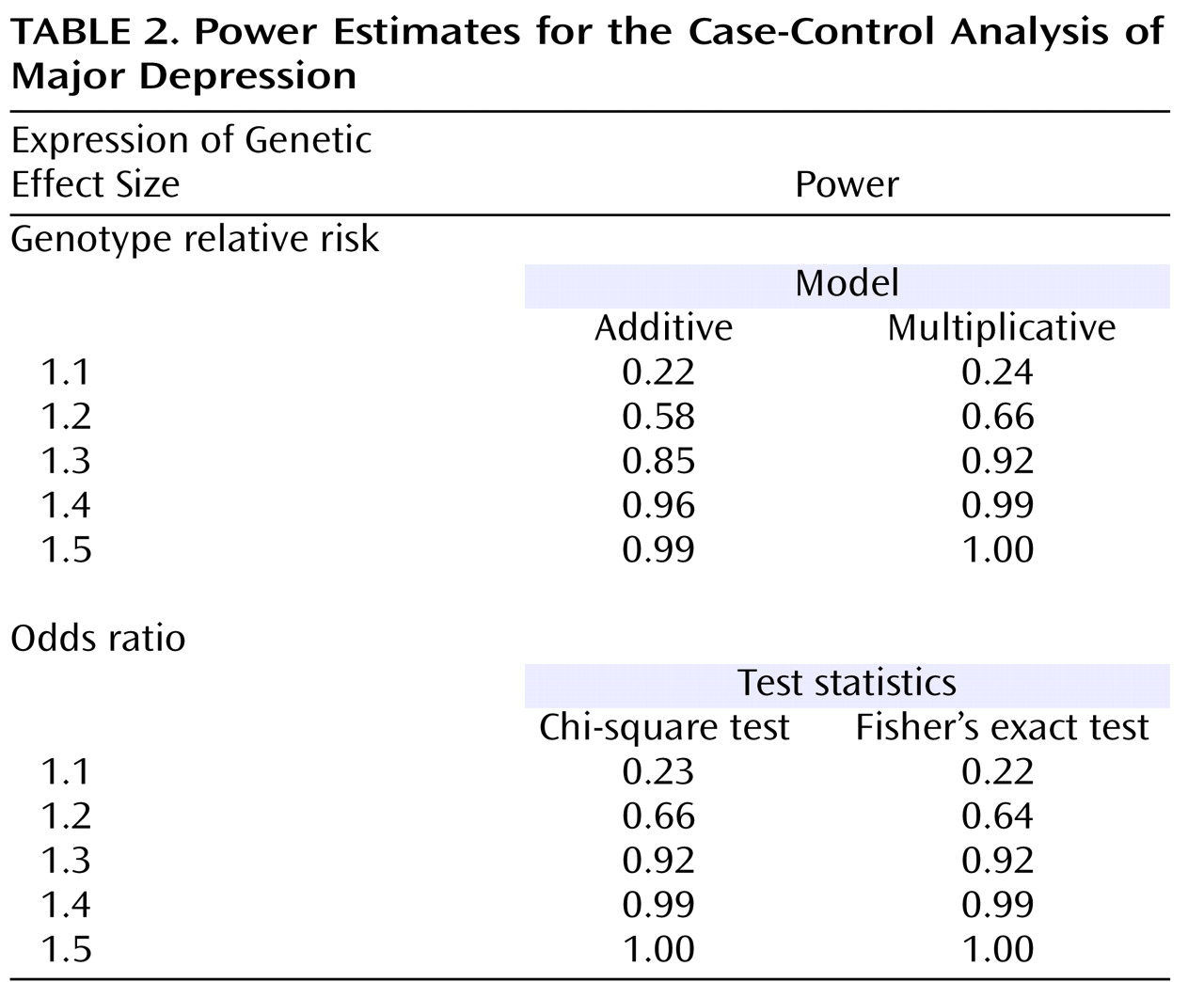

To pursue this issue, we undertook a two-tiered design. First, we tested whether the previously identified susceptibility haplotypes for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and panic disorder, i.e., the M23-M24 haplotypes C-T and T-A, were also associated with major depression with a group of 500 major depression patients and 1,030 population-based comparison subjects from Germany, all of German descent. Second, in addition to standard haplotype analyses focusing on the previously reported haplotypes, we also conducted an exploratory analysis with an additional 10 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and a novel haplotype-sharing approach. This step was performed in order to obtain a complete overview of the contribution of genetic variability at the G72 locus to major depression.

Discussion

Since its initial description

(1), the

G72 locus has become one of the most frequently replicated susceptibility genes for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

(5,

16 –

19) . In our previous work, we found identical

G72 alleles and haplotypes to be associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and panic disorder in independent samples from Germany

(4,

19) . Thus, we demonstrated for the first time the involvement of

G72 variants in three distinct clinical diagnoses.

Familial clustering across mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is a well-established finding in psychiatry

(20 –

22) . Findings from a large multicenter study provided evidence of linkage between major depression and a locus on 13q in proximity to

G72 (23) . Furthermore, 13q has also been implicated in the etiology of panic disorder

(55) . This prompted us to test whether

G72 was also involved in the etiology of major depression with a two-tiered design. Our primary analysis tested the specific hypothesis that the M23-M24 haploytpes C-T and T-A that we had previously found associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and panic disorder were also associated with major depression. With a large group of patients with major depression, we were able to identify an association between major depression and the M23-M24 haplotypes C-T and T-A, with C-T being more frequent and T-A being less frequent in cases. This finding was furthermore corroborated by the haplotype-sharing analysis, implicating an involvement of the distal region of

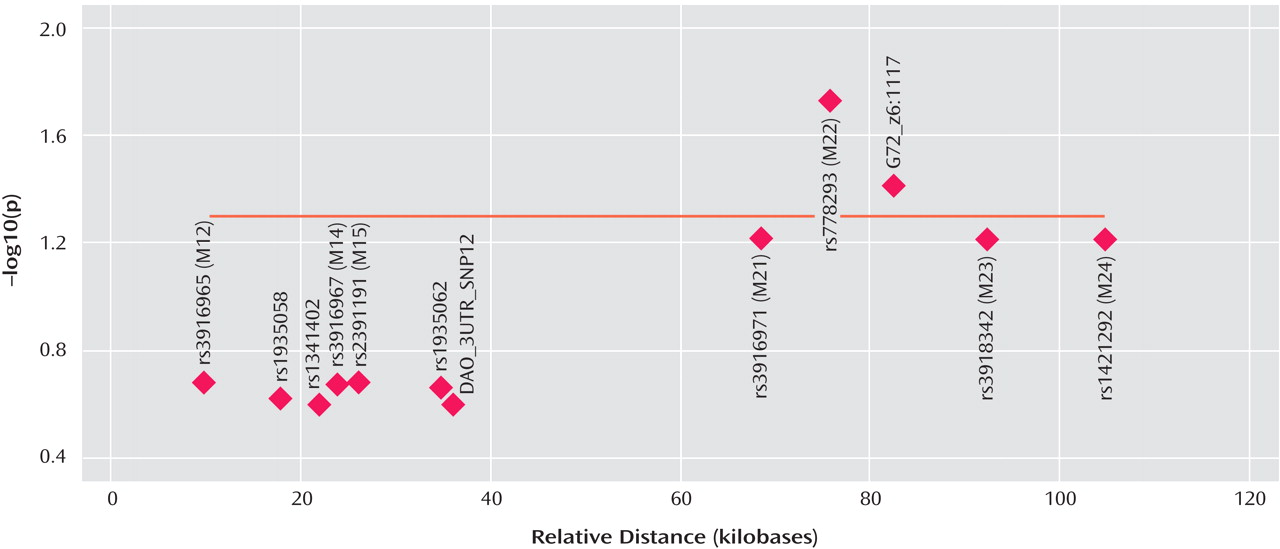

G72 in the etiology of major depression, with markers M22 and G72_z6:117 reaching significance after correction for multiple testing. Markers M23 and M24 did not reach significance (p=0.06) after correction.

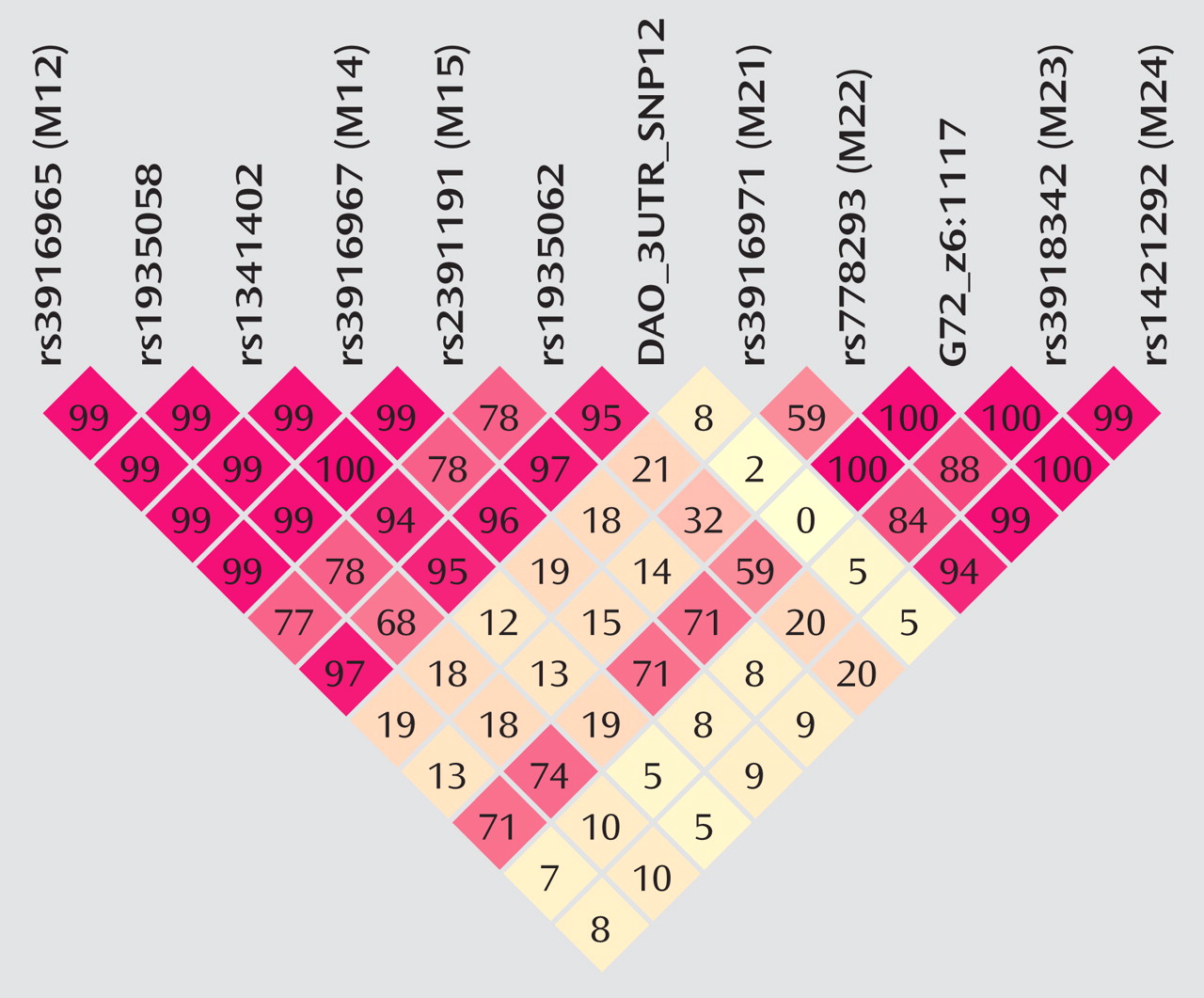

The fact that the standard haplotype analysis with UNPHASED and the haplotype-sharing analysis do not completely overlap in their results illustrates that these two approaches are fairly independent from each other because haplotype information is considered in different ways. At every marker position, the Mantel statistic tests whether there is an excess of sharing between case and comparison haplotypes around this SNP. Thus, it is a pointwise test taking into account the information of haplotypes to calculate the shared length as a measure of similarity. In contrast, UNPHASED tests for differences in haplotype frequencies between cases and comparison subjects in a logistic regression framework. However, given that the two identified sets of SNPs (haplotype-sharing analysis: M22 and G72_z6:1117; standard haplotype analysis: M23 and M24) are very close to each other, i.e., less than 10 kilobases, one can assume that both methods do identify the same region. The difference between the two approaches also explains why the haplotype-sharing analysis may highlight an SNP showing similar allele frequencies for cases and comparison subjects. The selection of the 12 G72 markers was not based on a systematic HAPMAP-based coverage of the region, but rather, we took into account the comprehensive association findings at the G72 locus and investigated the potential effect of those markers that had shown the most promising results with psychiatric phenotypes in previous studies.

Taking the results of the present study and the findings from our previous studies, there is now evidence for an association of

G72 with four major diagnostic entities: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and major depression. These association findings were obtained for

identical haplotypes, i.e., the T-A and the C-T haplotypes of markers M23 and M24, in one of the largest sample collections worldwide, including more than 3,000 individuals from German and Polish populations

(4,

19,

29) .

The association between this locus and major psychiatric disorder is still surrounded by some important caveats, however, given that the association findings with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and with specific subtypes, e.g., schizophrenia with mood episodes or bipolar disorder with psychotic features

(14,

29), have been obtained with different alleles, even in similarly sized and phenotyped samples of European origin, which may be due to a variety of reasons, ranging from so far undetected ethnic stratification to complex expression control

(5,

56,

57) . We therefore acknowledge that evidence remains that other

G72 variants play an etiological role. However, since this situation is not unique to

G72 but also affects other vulnerability genes for psychiatric disorders such as dysbindin

(58), we and others (M. O’Donovan and N. Craddock, American College of Neuropsychopharmacology meeting, December 2006) believe that it should not prevent further research in these loci, in particular, as the situation of different alleles being associated across studies may be consistent with so far undetected locus-locus interactions and subtle differences in the linkage disequilibrium structure

(59) . In contrast, we strongly advocate the continuation of this line of research. Identifying the functional variants of

G72 and other vulnerability genes will necessitate the refinement of both psychiatric phenotypes and molecular genetic research techniques. This line of research should be accompanied by further studies on the biological relevance of

G72 (1,

60) .

We further acknowledge that the genetic effect sizes we obtained for the individual M23-M24 susceptibility haplotypes are very modest. However, these odds ratios are within the range for reported associations with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

(5,

56) and are typical for the situation in complex disorders

(61) . Moreover, they are consistent with the notion of a polygenic etiology of complex disorders, such as psychiatric phenotypes, a concept that is gaining increased attention

(62 –

65) . For diabetes

(66,

67) and, very recently, for bipolar disorder

(68,

69), polygenic etiologies are supported by large-scale genome-wide association studies. In other words, the

G72 risk haplotypes that we have found associated with major depression are not likely to play a major role in the pathophysiology of this disorder when considered alone. However, within the context of a polygenic model, each person’s disease risk is influenced by the total burden of risk alleles or haplotypes they carry; taken for themselves alone, these alleles or haplotypes only confer very modest effects. Disease occurs when the burden of alleles or haplotypes crosses some threshold.

The major strength of our study lies in its large group size and robust recruitment and phenotyping procedures. A study with a smaller group size and less stringent methods may have missed the modest effect we describe

(34), in particular for an etiologically heterogeneous disorder like major depression

(70,

71) .

The challenge lying ahead is to dissect this heterogeneity. This will facilitate a better understanding of why susceptibility genes such as

G72 are consistently found associated across diagnostic boundaries. Ideally, one would want to pinpoint an (endo)phenotype linking different diagnostic entities together

(72,

73) . For the case of

G72, we could previously show that persecutory delusions constituted the common link between the association findings for schizophrenia and those for bipolar disorder in samples from Germany and Poland

(29) . Given our

G72 findings on panic disorder, the evidence for linkage between panic disorder and chromosomal region 13q

(55), where

G72 resides, and the notion that trait anxiety or worry are important predictors for the development, intensity, and persistence of persecutory delusions

(74,

75), we have furthermore advocated that not persecutory delusions per se but rather a trait of anxious affectivity might constitute this common link.

Therefore, in the present study, we set out to test this hypothesis by studying a potential association between

G72 and trait anxiety, i.e., neuroticism. In a large group of 907 individuals from the general population of the Rhineland region, we detected association between the M23-M24 risk haplotypes and neuroticism. In concordance with the findings on schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and now major depression, in which the C-T haplotype was associated with an

increased disease risk, the very same haplotype was associated with

higher levels of neuroticism, whereas the T-A haplotype was associated with

lower levels of neuroticism. Neuroticism has repeatedly been reported as a predictor and potential endophenotype for several psychiatric disorders, including major depression and schizophrenia

(24 –

28) .

The observation that identical

G72 haplotypes are not only associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and major depression but also with the personality dimension neuroticism suggests that

G72 may confer susceptibility to major psychiatric disorders through trait anxiety, which is shared by different diagnostic entities. Although replication of our findings in other samples of different genetic background is clearly needed, we would like to argue the case for a psychiatric genetic research framework that complements disorder-focused genetic association testing by the study of easily measurable intermediate phenotypes, e.g., personality dimensions, in large samples from the general population. Such an approach may further close the sometimes existing gap between disorder-specific genetics and sophisticated neurobiological endophenotypic strategies

(76) .