Discussion

The eponym “Othello syndrome” originates from Shakespeare’s tragedy in which the protagonist’s jealousy over his wife’s supposed infidelity ultimately leads him to commit spousal homicide. It refers to a content-specific delusion characterized by the fixed false belief that one’s partner has been or is being unfaithful. The typical patient is older than 40, has an acute onset of delusions, and has no past psychiatric history

(10) . Men are diagnosed with Othello syndrome more often than women

(11) . Patients with Othello syndrome ascribe personal meaning to benign events, misinterpreting the behavior of others to provide confirmatory evidence for their delusions.

In addition to being a syndrome in its own right, delusional jealousy may also appear as part of a constellation of symptoms in psychoses such as paranoid schizophrenia or in mood disorder with psychotic features. In one study, paranoid jealousy was found to be present in 0.17% of all psychiatric inpatient admissions over a 61-year period, although studies focused on the older population are likely to find a higher incidence

(12) . Delusional jealousy has also been described in conjunction with cerebral and cerebellar dysfunction, multiple sclerosis, encephalitis, neoplasms, epilepsy, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease, suggesting that underlying neurological conditions may serve to increase the risk of its occurrence

(13 –

16) . Several case reports suggest localized neuroanatomical correlates for Othello syndrome. Silva and Leong

(17) described a case of Othello syndrome in a patient following a left frontal lobe infarct. Narumoto et al.

(18) attributed the development of Othello syndrome to a right-sided orbitofrontal cortical lesion in one patient, while Soyka

(19) identified a case of delusional jealousy following a right-sided thalamic infarct. Shamay-Tsoory et al.

(20) correlated lesions in the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex with an impaired understanding of envy and associated this specific neuroanatomical finding with the pathological jealousy of Othello syndrome. Most cases of organic Othello syndrome do not appear to have a clear-cut association with lateralized brain dysfunction

(3) . Organic delusions in general have been associated with both left and right hemisphere pathology, including those of frontal origin. Because frontal lobe lesions are traditionally known to facilitate one’s inability to integrate and correct perceptual distortions in the face of contradictory evidence, frontal lobe dysfunction may be integral in delineating the etiology of the delusional jealousy seen in Othello syndrome

(21) .

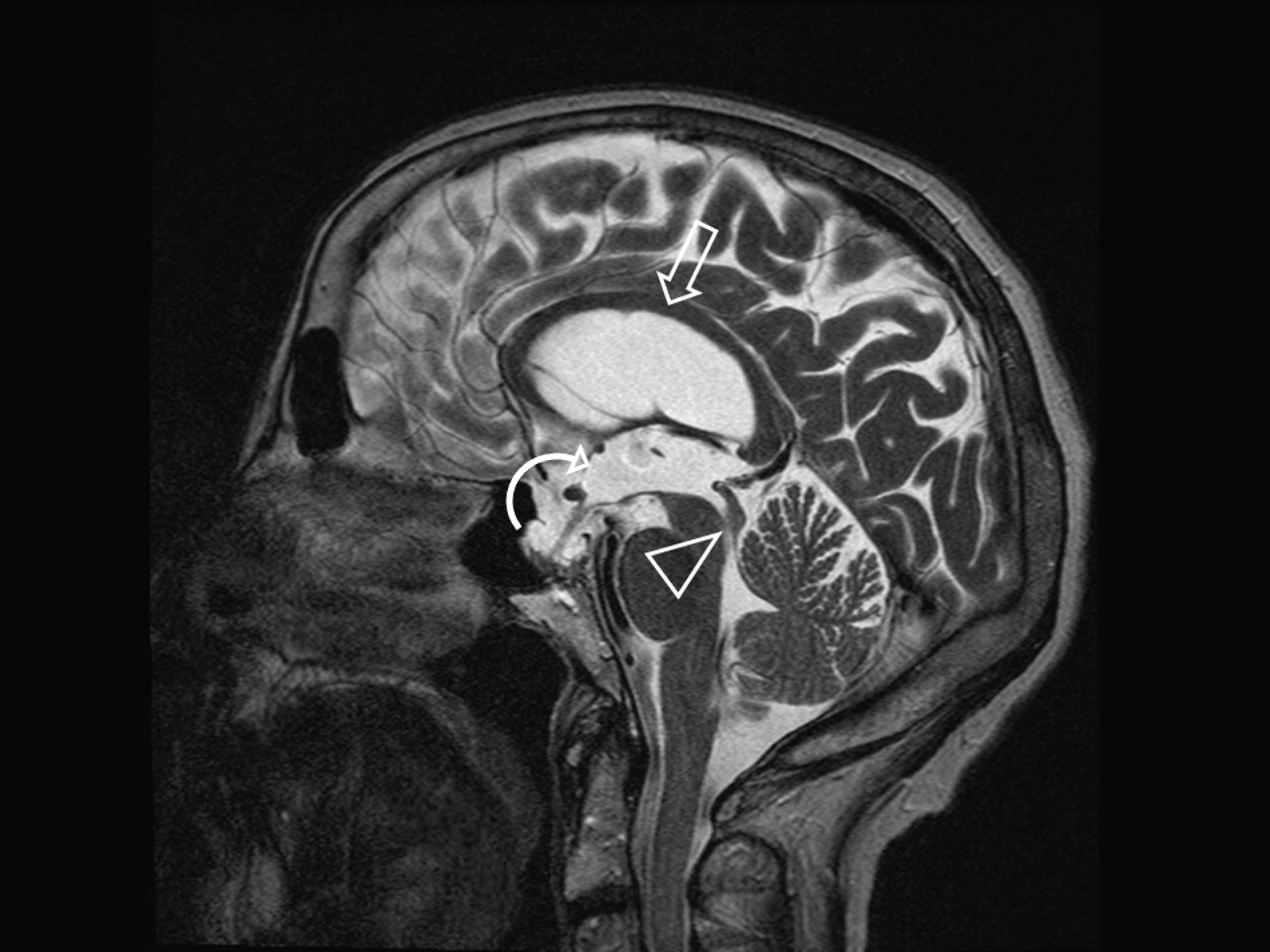

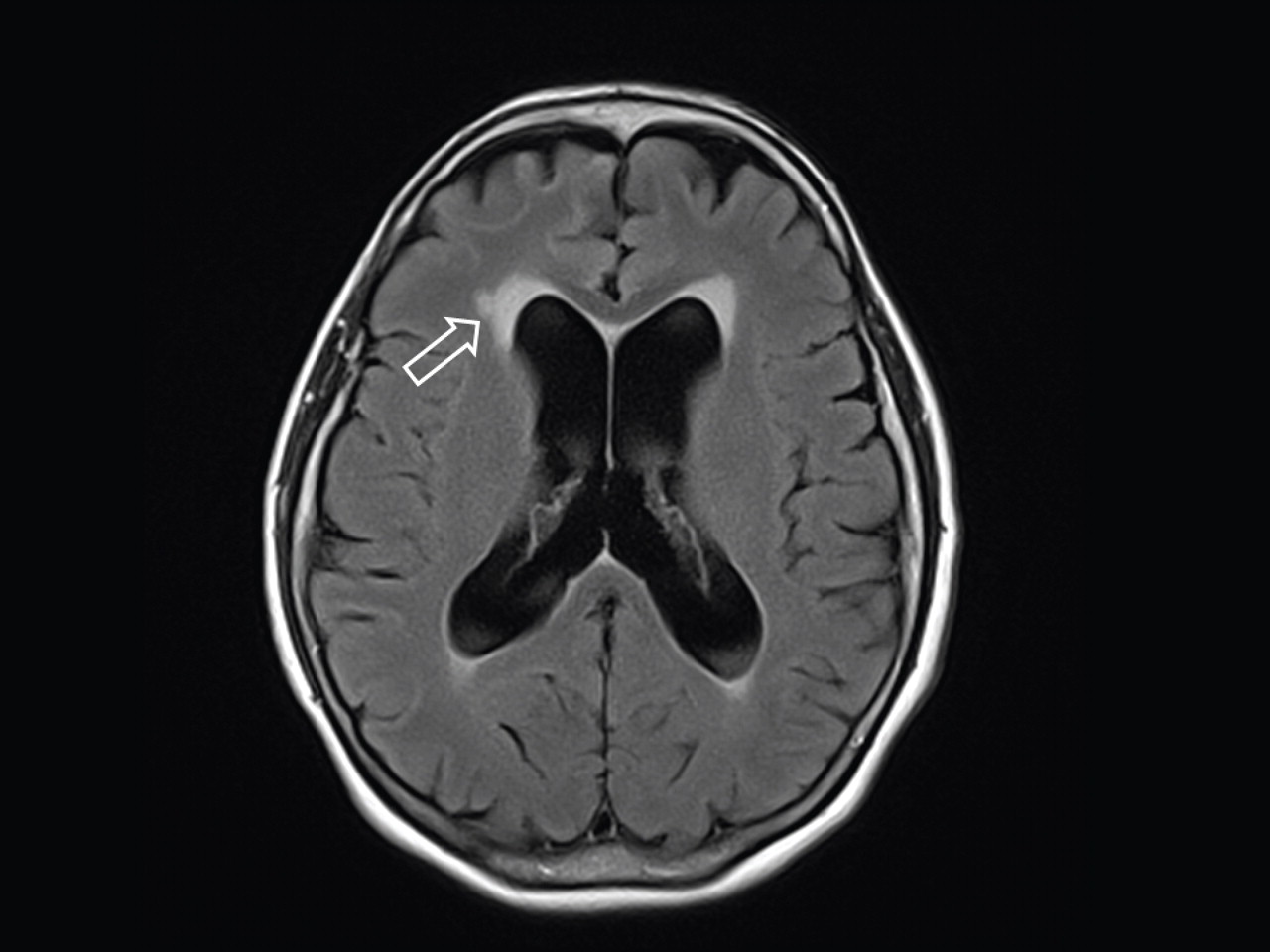

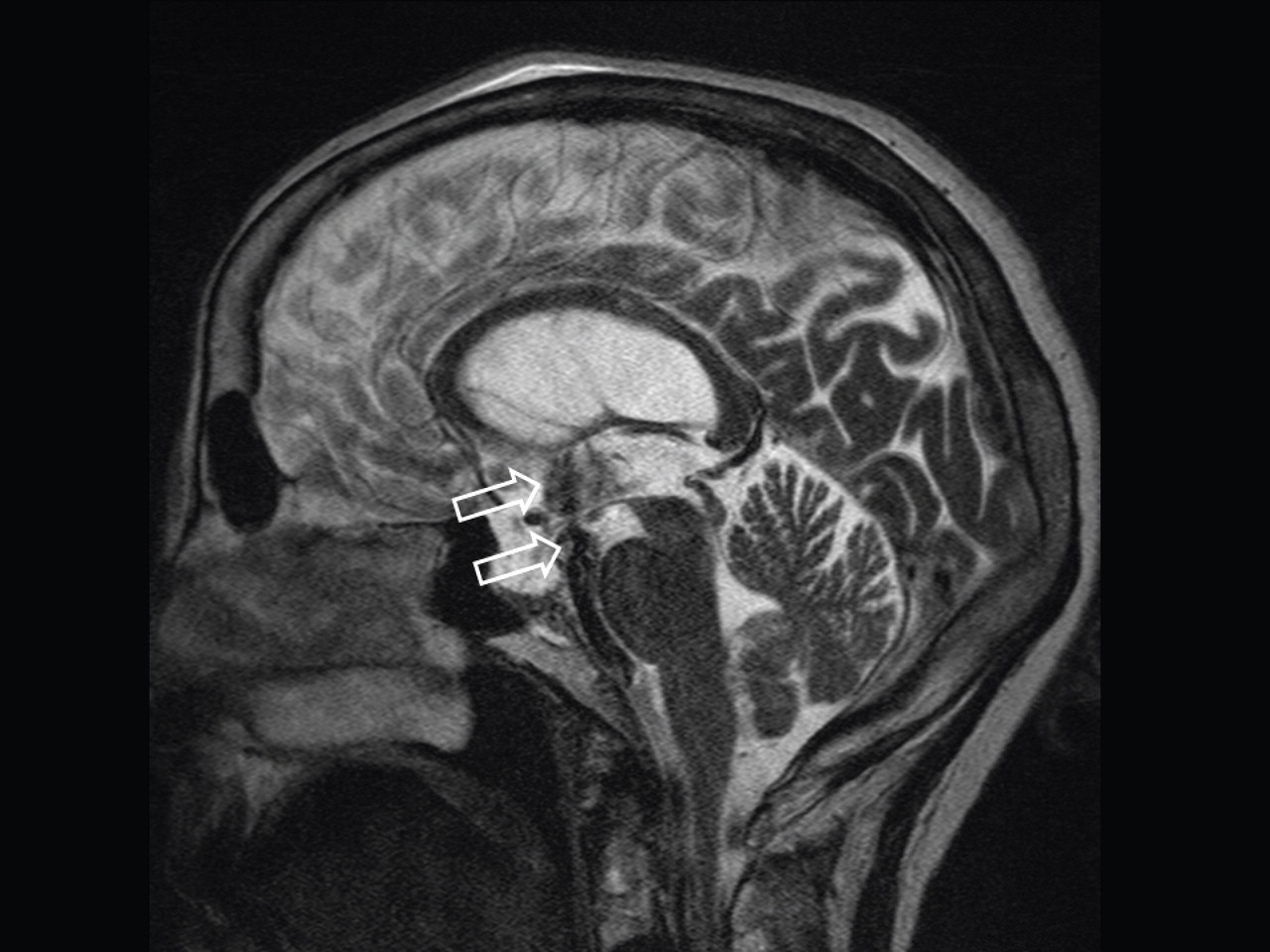

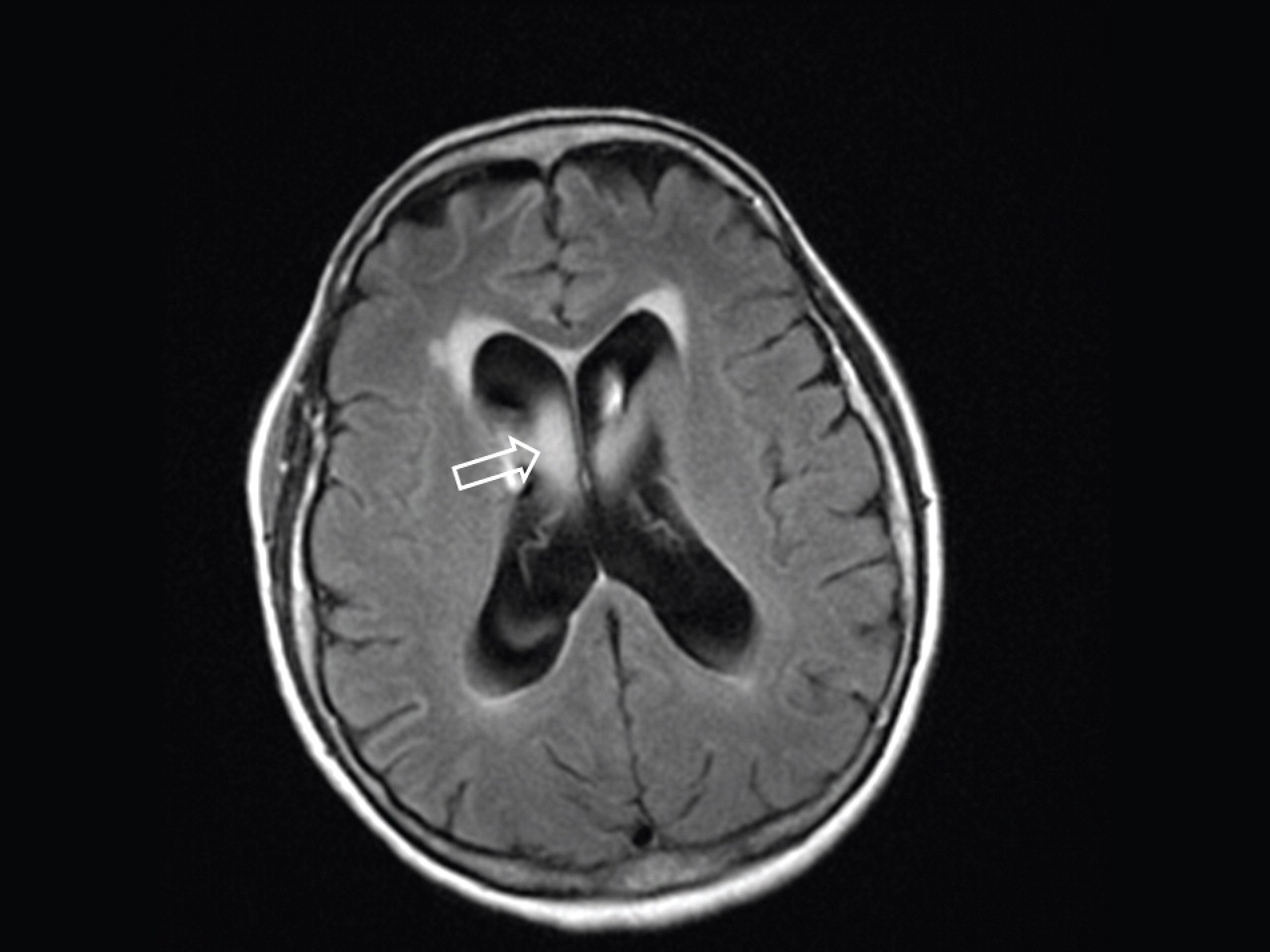

The lack of structural localizing MRI findings in our patient, particularly in light of the normal appearance of the frontal gray matter, makes it difficult to attribute her symptoms to right orbitofrontal lobe damage or thalamic dysfunction secondary to the effects of NPH, especially since the psychiatric and cognitive deficits were not relieved with surgical intervention. The clinical findings of impaired mental function and urinary disturbance associated with the NPH triad have been attributed to mass effect on the frontal white matter tracts by ventricular enlargement and tension

(22) . As such, cognitive findings in NPH may be considered focal or regional rather than global and potentially reversible with surgical intervention. In our case, lack of clinical improvement following ventriculostomy further argues against involvement of the periventricular white matter tracts in the pathogenesis of Othello syndrome. Previous studies have used functional imaging, such as functional MRI and positron emission tomography/single photon emission computed tomography, to evaluate differences in prediction error processing among patients with psychosis

(23), but not to our knowledge specifically in Othello syndrome. Although a structural neuroimaging study, such as computerized tomography or an MRI scan, is generally recommended as part of an initial evaluation of delusions with cognitive impairment

(24), functional imaging may enhance diagnostic specificity but is not presently recommended as part of the initial evaluation.

A medical basis for our patient’s symptoms is suggested by the temporal association between the onset of delusions and diagnosis of NPH, the presence of the classic NPH “triad,” and the absence of a significant personal or family history of psychosis or substance use. The present case illustrates the development of delusions in the context of NPH and in the absence of other persistent features of psychosis or general paranoia. This case is particularly unusual in that paranoid psychotic symptoms dominated the presenting clinical picture, with ataxia and urinary incontinence developing significantly later in the clinical course.

Many different conditions may present with suspiciousness and jealous delusions among the elderly. In addition to delusions due to NPH, the differential diagnosis for this patient may include dementia with psychotic features, delusional disorder independent of a general medical condition, depression with psychotic features, and intense suspiciousness in the absence of psychiatric illness

(25) . Schizophrenia, which may also present with delusions, is an unlikely etiology for our patient’s condition, since she did not exhibit hallucinations, disorganized thinking or negative symptoms, even before the ventriculostomy. Late-onset depression due to a medical or surgical condition may also be associated with psychotic or delusional symptoms

(26) . Because our patient did not meet formal criteria for major depressive disorder (she did not endorse weight changes, appetite changes, sleep changes, concentration difficulties, or feelings of guilt) or bipolar disorder type I or II, it is unlikely that her symptoms were part of an affective disorder.

The most common etiology of suspiciousness in late life is dementia with psychotic features, a diagnosis that bears resemblance to the former diagnostic entity of “late-life paraphrenia.” Prominent in European literature, this term was created to distinguish a unique syndrome of suspiciousness and paranoia primarily affecting older persons with mild cognitive deficits. People with this diagnosis are able to remain functional in their communities for months or even years after onset

(27) . The predominant delusions associated with this disorder are persecutory or somatic in nature. Persecutory delusions revolve around either one single theme or a series of connected themes, such as family and neighbors conspiring against the delusional older person or being sexually abused. These delusions frequently wax and wane in severity and content but may become most prominent when a patient’s environment is changed abruptly. Age-related subcortical degeneration may disrupt neurotransmission and higher brain functions, which in turn contributes to a deficiency in maintaining attention and filtering information, symptoms that have been associated with delusions and psychosis. It is important to differentiate true psychotic symptoms from misperceptions resulting from a patient’s compromised capacity to organize perceptual information. In a survey of Alzheimer’s disease patients, 34% endorsed delusions, and 16% endorsed delusional jealousy

(28,

29) . Patients who endorsed delusional jealousy did not significantly differ in age, age at onset, gender, educational level, or MMSE scores from patients who did not endorse such delusions. The average age of the patients with “accusatory behavior,” which included but was not limited to delusions of infidelity, was 74 years

(30) .

Upon admission, our patient presented with cognitive impairment. It was difficult to assess whether this represented a subclinical dementia that may have been present before her hospitalization or a result of the ventriculostomy procedure. In the former scenario, the patient’s NPH may have actually presented as the “classic triad” of dementia, a gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence; the jealous delusions may have been a product of the dementia. The patient’s history of late-life-onset depression and anxiety several years before presentation further supports the possibility of an impending dementia. The minimal microvascular changes on the patient’s MRI make a vascular etiology of dementia less likely. Since NPH is one of the few treatable causes of dementia, an improvement in cognitive performance might be expected with ventriculostomy if the dementia were due to NPH alone. Although the patient’s gait impairment and urinary incontinence improved with surgery, her cognitive impairment and jealous delusions did not. Notably, it has been suggested that cholinesterase inhibitors may have antipsychotic effects in patients with cognitive impairment with psychotic features

(31) . This therapeutic effect was not seen in our patient, whose delusions did not improve with the introduction of donepezil, although the duration of the trial was not sufficient to definitively conclude lack of efficacy. Although the etiology of our patient’s cognitive deficits remains uncertain, the lack of improvement with surgical and medical intervention increases the likelihood of an underlying insidious dementia process with psychotic features.

Late-onset delusional disorder is another frequent cause of suspiciousness in late life. Delusions, often of being persecuted by family and friends, usually center on a single theme or a connection of themes, as was seen with our patient’s jealous delusions about her husband’s infidelity. An association has been reported between delusional disorder and certain premorbid personality disorders (e.g., schizotypal, paranoid), early life trauma (e.g., sexual or physical abuse), hearing loss, immigration status, and socioeconomic status

(32,

33) . Suspiciousness and paranoid behavior were found in 17% of persons in one community survey of elderly persons

(34), and a sense of persecution was reported in 4% of elderly persons in another survey

(35) . When evaluating delusional disorder as a possible diagnosis for the patient’s condition, special attention must be paid to the DSM-IV-R diagnostic criterion E, which specifically states that delusional disorder can only be diagnosed if the symptoms cannot be better accounted for by the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition. Since our patient had a known neurological condition, we must exercise caution when trying to account for her residual psychiatric and cognitive symptoms with the diagnosis of delusional disorder.

Given the presence of the NPH triad in our patient and the fact that the NPH represented a potentially reversible cause of her symptoms, it was appropriate to consider surgery while carefully weighing the risks and potential benefits of the interventions available. The primary treatments of NPH—catheter shunting and third ventriculostomy—improve cerebral blood flow by reducing the buildup of CSF

(36) . Third ventriculostomy, which was used in our patient, is a safer and less invasive alternative to shunting. Third ventriculostomy can only be used in cases of a “noncommunicating” hydrocephalus, in which ventricular outflow is obstructed before it reaches the subarachnoid space. One such cause is aqueductal stenosis, whereby once the CSF is diverted through the ventriculostomy opening into the subarachnoid space, it can be efficiently absorbed by normal arachnoid granulations. In third ventriculostomy, a neuroendoscope—a tiny camera designed to visualize small and difficult-to-reach surgical areas—allows the surgeon to view the ventricular surface using fiber-optic technology. The scope is guided into position and a small opening is made in the floor of the third ventricle, allowing CSF to bypass the obstruction. The majority of patients, however, are not candidates for the ventriculostomy procedure because the point of obstruction may be at the granulations themselves, indicating the presence of a “communicating” hydrocephalus.

Studies have shown that up to 93% of patients have dramatic improvements in gait after surgical treatment of NPH, in contrast to only 50% of patients showing improvements in cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms

(37) . Although the rate of improvement is variable after surgical intervention, patients generally show improvement in gait and incontinence within 3 months of the intervention, and in cognition within several more months

(38) . Whereas gait and incontinence improved as predicted in our patient after surgery, her delusions persisted. This leaves the clinician with the challenge of trying to ameliorate symptoms through pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions in an effort to enhance quality of life.

According to the APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias

(24), interventions for cognitive impairment with psychotic symptoms should be guided by the patient’s level of distress and the risk to the patient and caregivers. If the patient is neither agitated nor combative and the psychotic symptoms cause minimal distress, then nonpharmacological interventions, including reassurance and redirection, should be considered before a medical trial. Supportive psychotherapeutic approaches and cognitive behavior interventions have been found to be beneficial in these cases

(39) . Supportive therapy has been demonstrated to alleviate anxiety and engage the patient in a discussion about the delusions, thereby strengthening the therapeutic relationship between clinician and patient

(40) . Cognitive approaches that rely on reality testing to reduce the extent of delusional thinking have also been shown to be effective in certain patients with chronic delusions

(41) . Educating caretakers about the patient’s delusional symptoms and encouraging them to maintain patience may contribute to reducing the patient’s emotional distress

(42) . Research studies with increasingly rigorous parameters to measure biological markers, treatment response, and outcome will assist in better defining the value of different nonpharmacological interventions in patients with delusions. Behavioral, psychosocial, and psychotherapeutic treatments are particularly important in light of the potential for dangerous side effects of pharmacotherapy.

When nonpharmacological treatment is unsuccessful in reducing distress, as was the case with our patient, APA guidelines recommend a trial of low-dose antipsychotic medication

(38) . The use of antipsychotic agents carries a significant obligation for safety monitoring; however, given the distress associated with psychosis in cognitively impaired patients, these psychotropic agents are often necessary for clinical relief. A recent review has extensively summarized the risks and benefits of the use of antipsychotic medications in older adults with dementia

(43) . As the overall side effect burden appears to be lower with second-generation agents, drugs in this class are usually selected first to treat psychotic symptoms in dementia patients. The CATIE-AD trial did not find significant differences in efficacy or tolerability among the second-generation antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of psychotic symptoms in dementia patients, although the time to discontinuation due to lack of efficacy was longer for olanzapine and risperidone than for quetiapine

(44) . With respect to delusions specifically, a retrospective chart review showed that both first- and second-generation antipsychotic medications were efficacious in restoring competency in the majority of incompetent criminal defendants diagnosed with delusional disorder

(45) . The neuroleptic pimozide has historically been recommended for the management of delusional jealousy, although no definitive trial-based data exist to guide its preferential use in the context of NPH or even of delusional disorder over other available atypical antipsychotics

(46 –

48) . Some clinicians may opt to treat delusional disorder with a trial of primozide, in lieu of other antipsychotics, based on the patient’s tolerability of the medication’s distinctive side effect profile. Since there are few relative efficacy data to guide the choice among second-generation antipsychotic agents, the choice is based most often on tolerability of side effects. In addition to antipsychotics, other forms of therapy such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, clomipramine, and ECT have also been shown to have beneficial effects in patients with chronic delusions.

The existing literature on psychiatric features in NPH is scant. However, with the graying of our population, this age-related condition is likely to be encountered with greater frequency in the clinical setting. While not always amenable to treatment, recognition of psychosis as a potential presenting symptom of NPH may aid in its early detection and thereby improve both clinical course and quality of life.