In hospitals, overcrowding and excess staff workload have been widely recognized as a serious problem for both patients and staff

(1 –

7) . Overcrowding, as indicated by excess bed occupancy, has been shown to be associated with increased hospital infections and patient mortality

(3 –

5) . Other reports have found that a high patient to nurse ratio is related to adverse patient outcomes

(1,

6,

7) and increased self-reports of staff burnout and job dissatisfaction

(1) . Furthermore, self-reported excess staff workload appears to be associated with an increased risk of depression

(8 –

10) . However, research on the associations between hospital overcrowding and mental health in hospital staff is lacking.

In this report, we present results from a prospective study of 6,699 nurses and 641 physicians from 203 somatic illness wards in 16 Finnish hospitals. Monthly bed occupancy records for each ward over a 5-year period and daily information on antidepressant prescriptions purchased by the staff enabled us to assess the effect of excess occupancy rate on the likelihood of new antidepressant treatment among hospital employees.

Results

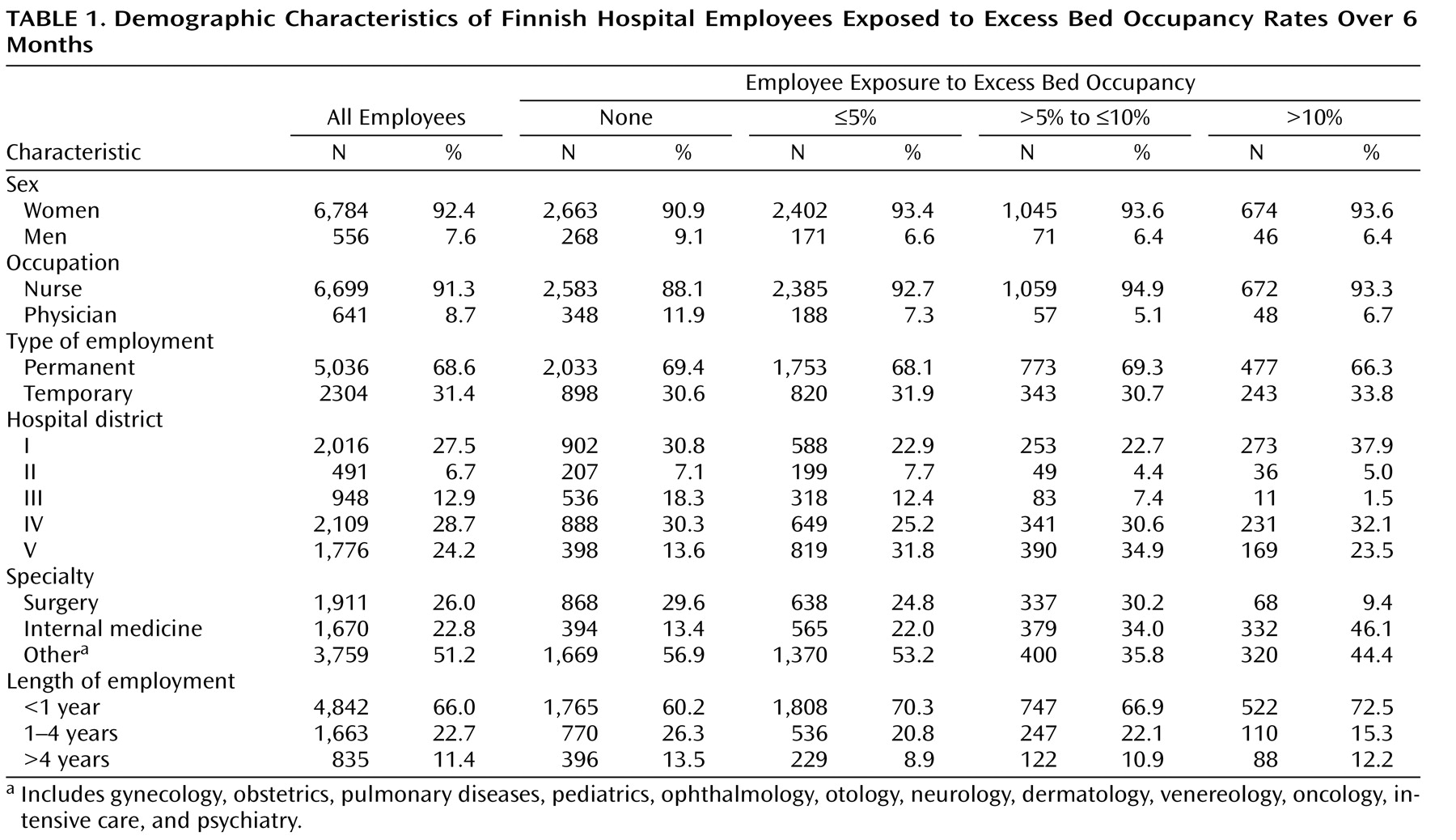

Demographic characteristics of employees at the beginning of the follow-up period are presented in

Table 1 . The majority of participants (91%) were nurses and 69% had a permanent job contract. At the beginning of the follow-up period, 40% of participants were working in a ward with no excess bed occupancy, 35% in wards with an excess bed occupancy of ≤5%, 15% in wards with an excess bed occupancy of >5% to ≤10%, and 10% in a ward with an excess bed occupancy of >10%. Variation in bed occupancy was found between hospital districts, and excess bed occupancy was more common in internal medicine than in surgical wards and other specialties. Short job contracts were more common in groups with high bed occupancy.

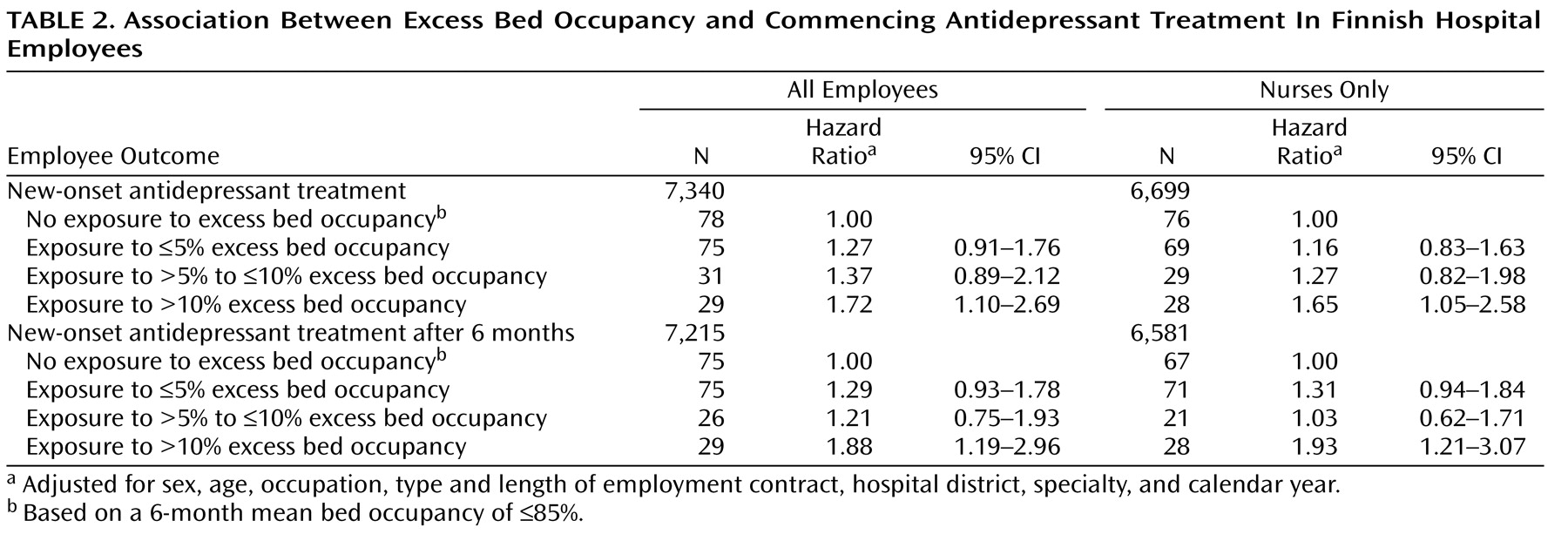

Table 2 shows the association between the mean level of bed occupancy during a 6-month period and subsequent antidepressant treatment. After adjustment for potential confounding factors, excess bed occupancy of >10% was found to be related to a 1.7-fold increase in risk of new antidepressant treatment. A similar effect (hazard ratio=1.7) was found in the analysis for nurses alone (

Figure 1 ). The association followed a dose-response pattern for a continuous measure of bed occupancy rate (all employees: p=0.013; nurses only: p=0.031). The time-dependent interaction between bed occupancy rate and the follow-up period was nonsignificant (p=0.145); thus there was no evidence that the association would have changed over time.

The effects of overcrowding after a 6-month time lag (i.e., after a period of potential untreated depression subsequent to exposure) are also shown in

Table 2 . These analyses reveal a similar or even slightly stronger effect of ward overcrowding (all employees: hazard ratio=1.9; nurses only: hazard ratio=1.9). As a test of sensitivity, we repeated these analyses using a 12-month rather than a 6-month time lag. The effect of ward overcrowding was diluted with this extended time period (all employees: hazard ratio=0.91, 95% CI=0.55–1.51; nurses only: hazard ratio=0.97, 95% CI=0.59–1.61; results not shown).

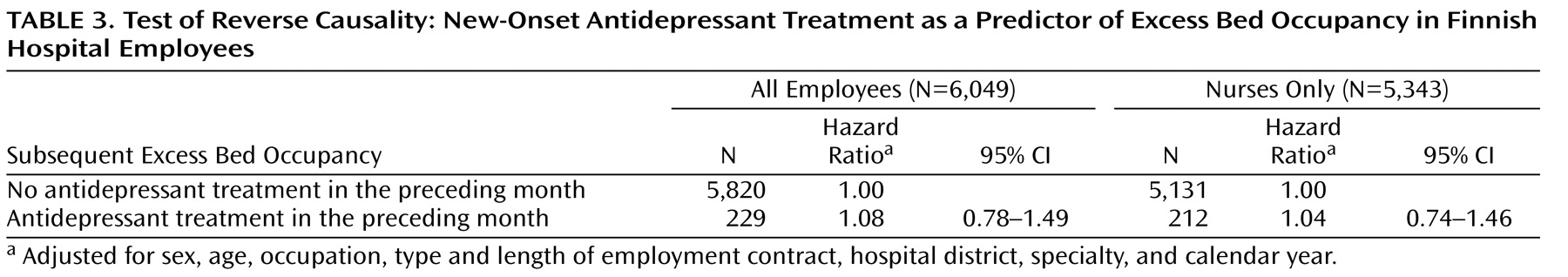

Table 3 shows a test of reverse causality—that is, whether antidepressant use in the preceding month predicts overcrowding in the next month among employees previously not exposed to overcrowding. The results suggest that this is not the case.

Discussion

Our results indicate that ward overcrowding, expressed as excess bed occupancy, predicts new periods of antidepressant use among hospital nurses and physicians. We also found that the relationship between excess bed occupancy and antidepressant use followed a dose-response pattern. Direct comparison with earlier studies is not possible because our study is unique in many respects. For instance, in this study bed occupancy rate was assessed each month over a 5-year period, which has not been previously feasible. Furthermore, this study had daily data on employees’ antidepressant purchases.

The reason overcrowding may affect the mental health of employees is related to its association with high workload. Overcrowding will increase workload, for example, if an insufficient number of employees is available to cover patient peaks. Workload may increase even if agency staff are used to help cover it, as a certain level of mentoring will be involved. Overcrowding is also related to poor patient outcomes

(3 –

5), which implies that patients are sicker and have increased needs. It is also noteworthy that associations between high patient to nurse ratios and burnout among hospital nurses

(1) and between self-reported high job demands and incidence of depressive disorders and antidepressant use have been reported

(8 –

10) .

Antidepressant medication can be considered as a proxy measure for clinically significant depressive or anxiety disorders. However, many affected individuals wait long periods after a depressive episode begins before initiating pharmacologic treatments. With a 6-month time lag we replicated the robust association between overcrowding in the ward and subsequent antidepressant use. Earlier studies, which focused on the first episode of depression rather than new-onset depression, found a large variation in the time lag between the onset of depression and seeking help, ranging from 4 months

(18) to several years

(19,

20) .

At the individual level, depression is associated with diminished productivity and might therefore contribute to a failure to discharge patients in a timely manner, a potential source of ward overcrowding. To address this possibility of reverse causality between occupancy rate and depression, we tested whether antidepressant use predicted overcrowding in a subpopulation previously unexposed to excess bed occupancy. These analyses provided no evidence to support reverse causation as an explanation for the association between ward overcrowding and antidepressant use.

Some limitations of our study are noteworthy. First, selection of variables included in the analysis was dependent on the availability of data in source registers. This meant that some variables of interest, such as marital status and adverse events outside work, were not available to this study

(24,

25) . Register data on antidepressant prescriptions are based on a visit to the physician and cover virtually all outpatient prescriptions in Finland. Lack of information on the diagnosis for which antidepressants were prescribed made it impossible for us to exclude those prescriptions that were for indications other than mental disorders, such as chronic pain or sleeping problems.

Furthermore, as our measure of depression was antidepressant treatment, we were not able to take account of employees with unrecognized or untreated depression or those treated using nonpharmacological methods. Thus, we cannot fully eliminate the possibility of reverse causality arising from a protopathic bias

(21,

22) if reduced productivity among employees with untreated depression substantially influenced ward-level overcrowding. Moreover, differences in treatment practice among physicians may also affect the choice of treatment (i.e., whether or not to prescribe antidepressants). However, such variability is likely to be random in relation to bed occupancy and is probably not a source of major bias in our results.

The possibility of unmeasured confounding can never be totally ruled out in observational studies such as ours. However, adjustment for sex, age, occupational group, and type of employment contract allowed us to control for confounding by these risk factors for depression

(15,

16) . Adjustment for hospital district enabled us, to some extent, to control for area differences in the prevalence of depression and variation in organizational structure and occupational health service practices between hospital districts. Further adjustment for specialty allowed us to partially control for variation in organizational factors between specialties, and by adjusting for calendar year we sought to control for period effects on antidepressant use.

Finally, our cohort was from public sector hospitals and was 92% female and ethnically homogeneous (mostly white employees). Future research with more diverse samples is needed to evaluate the generalizability of our findings.

With the limitations of our study in mind, we conclude that overcrowding in hospital wards may have an adverse effect on the mental health of employees. Our findings have important implications for hospital administration. Depression is a serious problem worldwide in terms of human suffering, disability, mortality, and productivity

(23,

26) . Overcrowding may not only be a consequence of lack of resources but also a byproduct of patient flow problems

(27) . As depression is a major cause of work disability, our findings suggest that minimizing overcrowding in hospital wards would not only be beneficial to patients but should also be regarded as a target worthy of priority in the promotion of mental health and working capacity among hospital staff.