Some 0.8%–1.5% of all infants in developed countries are born with very low birth weight (VLBW), defined as a birth weight below 1500 g

(1,

2) . Developments in perinatal and neonatal care in recent decades have allowed an increasing number of VLBW infants to survive, and these individuals now constitute a substantial portion of the adult population. Although most such infants survive without major disabilities, VLBW children, adolescents, and young adults are at increased risk for psychopathology, with both internalizing and externalizing symptoms

(3 –

9) . Studies of their mental health outcomes have produced inconsistent results, however

(10,

11) . One reason for this may lie in the heterogeneity of VLBW infants. Some have suffered from intrauterine growth retardation in addition to being born preterm. Indeed, there is evidence that VLBW individuals who are born small for gestational age differ in later mental health outcomes, such as depression

(12) .

Discussion

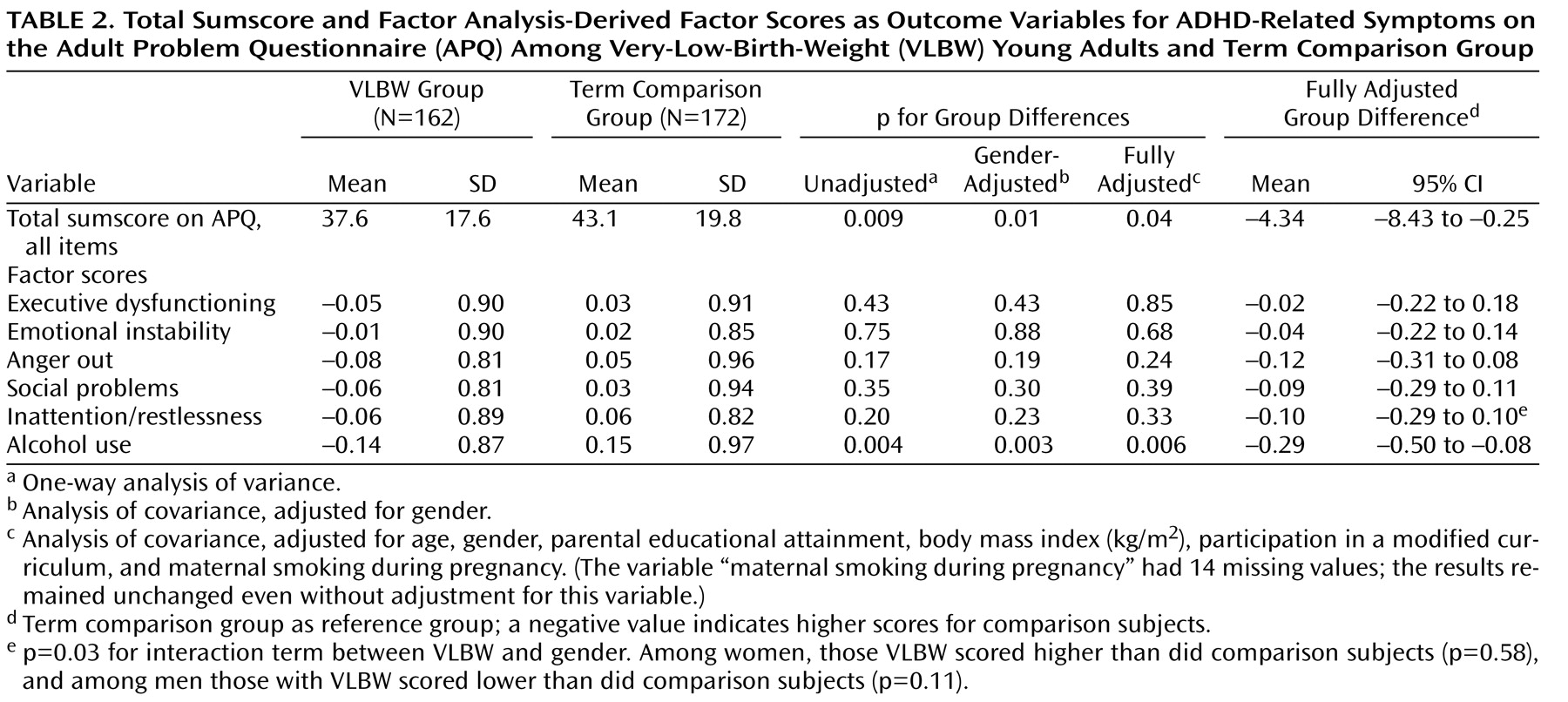

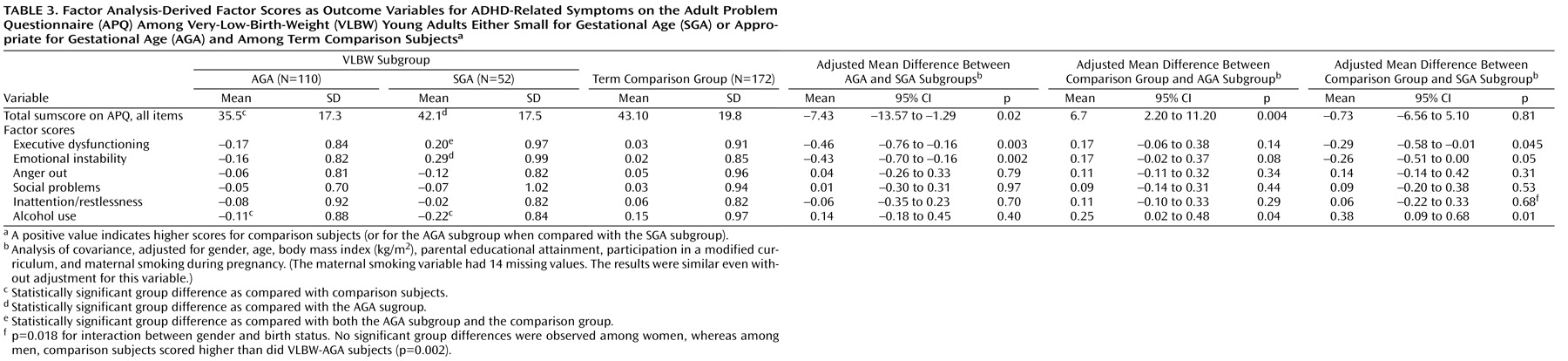

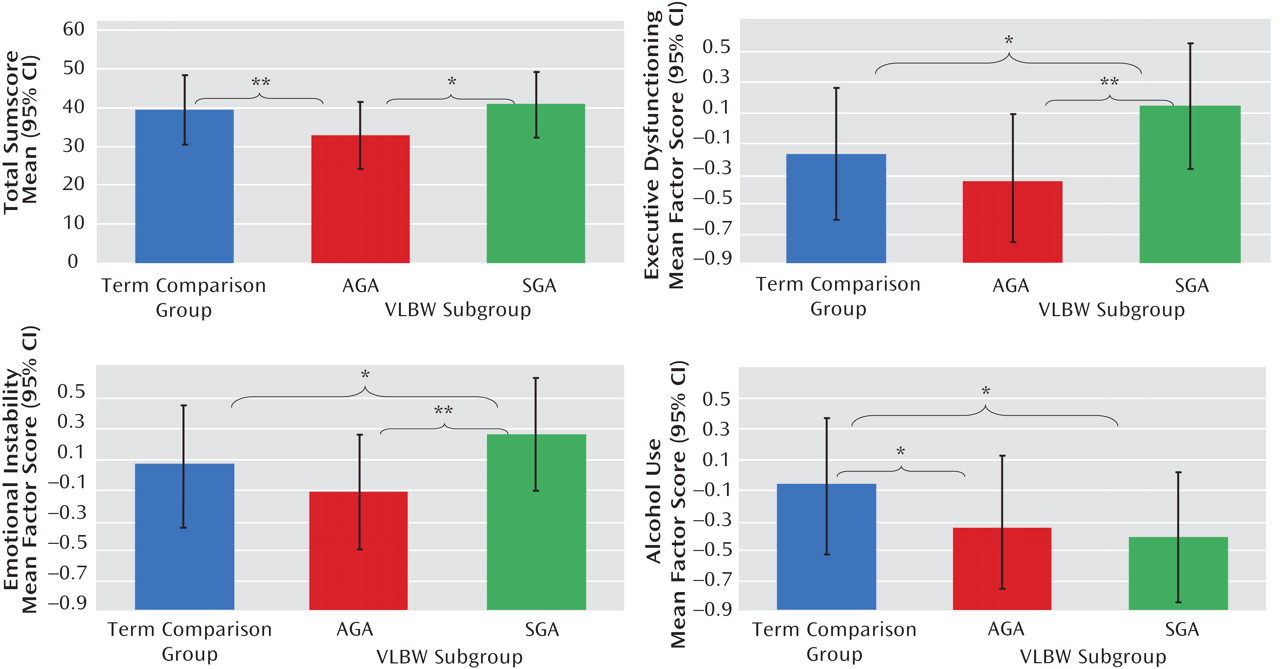

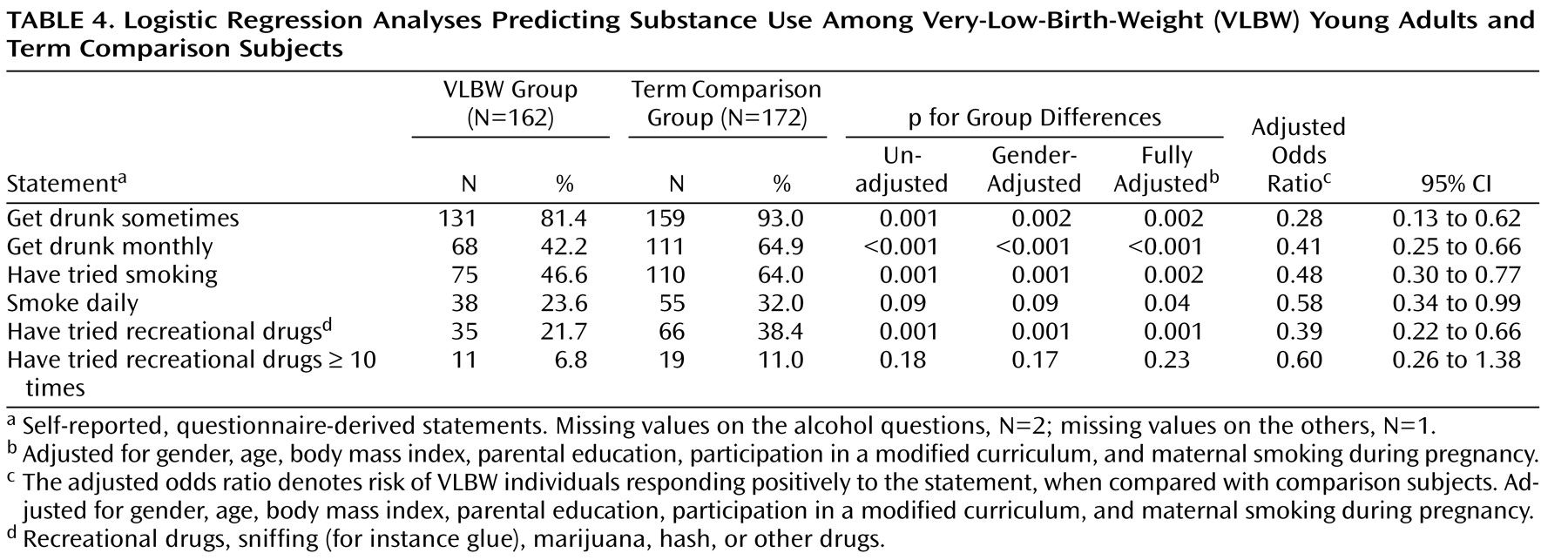

Our VLBW young adults born SGA reported more executive dysfunction and emotional instability than did their AGA peers and term comparison subjects, suggesting poorer adult outcomes for those born both too early and too small. VLBW individuals whose birth size was AGA, in contrast, fared well. VLBW young adults as a group did not report more ADHD-related symptoms; they did, however, report less substance use. Among determinants of fetal growth, maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with increased ADHD-related behavioral symptoms.

Studies show that VLBW individuals are at risk for ADHD symptoms in childhood and adolescence

(3,

5 –

9,

13 –

15) . While “common” ADHD is usually strongly associated with elevated rates of substance use

(27), research also indicates, somewhat counterintuitively, decreased risk-taking behavior among adolescents and young adults born preterm

(4,

10,

14,

16,

17,

32) . Indeed, it has been proposed that the ADHD of preterm children is more “pure”

(13), characterized by a more even gender distribution and by less hyperactivity in relation to inattention, and that it is less frequently accompanied by comorbid disorders

(7 –

9,

13) . This proposed distinct phenotype may reflect different biological mechanisms underlying the disorder. In our study, the combination of increased executive dysfunction, emotional instability, and less alcohol use among VLBW-SGA adults thus fits the theory of a distinct phenotype. Our other findings from the substance use survey, showing substantially less substance experimentation and use in the VLBW group, further support this idea of fewer comorbid disorders.

In disagreement with reports pointing to an ADHD with more inattention in relation to hyperactivity among former VLBW infants

(4,

7,

9), we found no increase specifically in symptoms of inattention. It is thus conceivable that either the inattention/restlessness subscale fails to identify inattention satisfactorily or that self-rating questionnaires in general are an unsuitable method for exploring this particular trait.

While the relationship between VLBW and ADHD symptoms in childhood is established, this relationship in adulthood is less clear. ADHD usually declines with age, and the risk of symptom persistence is greatest among children with the hyperactive delinquent type of ADHD

(28) . In agreement with our results, the few findings published on ADHD symptoms in young adulthood have failed to demonstrate any excess of

self-reported ADHD symptoms in VLBW individuals relative to comparison subjects

(4,

15) . However, in contrast to self-reports, the parents of these VLBW individuals rated their young adults as having significantly more ADHD symptoms than did parents of comparison subjects. In a study of extremely-low-birth-weight (<1000 g) adolescents, study subjects scored higher on ADHD symptoms according to parent report but not according to self-report

(14) . The reason for this discrepancy between parent reports and self-reports is unclear. It may be related to parental overprotection after a preterm birth or to denial

(14) or recalibration

(14) among the young VLBW adults. In any case, in the absence of studies with objective criterion variables, we cannot know whose ratings may be more biased, the parents’ or the VLBW young adults’. Recently, Dalziel et al.

(32) reported that a group of adults born at a mean gestational age of 34.1 weeks and a mean birth weight of 1946 g scored nonsignificantly lower than term comparison subjects on the Brown Attention Deficit Disorder scale, a result in line with ours. Previous observations have shown that extremely-low-birth-weight young adults and comparison subjects rate their health-related quality of life equally high, despite more disability in the extremely-low-birth-weight group

(3,

33) . Possibly, this phenomenon affected the ratings on the APQ in our study as well, with VLBW individuals in general and VLBW-AGA in particular reporting low ADHD-related behavior relative to term comparison subjects.

The underlying mechanisms for VLBW-SGA individuals reporting excessive ADHD-related behaviors may be biological as well as psychosocial

(6) . Biological programming of the developing brain due to a nonoptimal fetal environment or prematurity-associated illness in the postnatal period may interfere with neuronal organization and thus modify the later psychological phenotype. In studies of low-birth-weight children (<2500 g)

(30), even of those within the term-born range

(34), small body size at birth predicts behavioral symptoms of ADHD. Our findings suggest that intrauterine growth retardation, for which SGA serves as a proxy, is a more important predictor for later ADHD-related behavioral traits than is prematurity per se. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that ADHD, being a highly heritable disorder

(27), and prematurity have a common genetic origin. After birth, the psychosocial environment and parenthood also affect the development of the VLBW individual: being born preterm—especially if SGA—is associated with less favorable parent-child and family interactions at age 4 months

(35) . A VLBW birth initially gives rise to maternal psychological distress, with high-risk infants causing them the most distress

(36) .

Our results parallel prior findings on the psychological profile among VLBW young adults from this same cohort. We recently demonstrated

(12) that their depression was modified by their intrauterine growth pattern, as reflected in SGA status. The VLBW group reported less depression, although as in the present study, this was confined to those born AGA; those born SGA presented with more depression

(12) . With regard to their temperamental characteristics, VLBW young adults (both AGA and SGA) reported less fun-seeking behavior than did term comparison subjects

(21), a trait fitting well their lower rate of substance experimentation reported here. As for personality, the VLBW group displayed more conscientiousness and less impulsiveness, excitement seeking, hostility, and openness to experience

(19) . They also leave the parental home and start cohabiting with an intimate partner at a later age

(20) . We can conclude from these studies that VLBW adults are, on average, more dutiful, more cautious, and less prone to risk-taking behaviors such as substance use, whereas their psychopathology seems to vary according to intrauterine growth patterns: the higher degrees of depression and ADHD symptoms are confined to those born SGA. Obviously, replication of these findings is necessary to confirm these conclusions.

The strengths of this study include a well-characterized cohort with comprehensive perinatal data, which allows us to explore the impact of early life events on adult health. In particular, separating the SGA and AGA subgroups in the analyses broadens the perspectives of how VLBW may affect adult health, since it has been suggested that preterm individuals suffering from intrauterine growth retardation are at higher risk for decreased cognitive capacity in childhood than their AGA peers

(37) . Valuable information may be overlooked in failing to separate SGA and AGA subgroups. It should be borne in mind, however, that definitions of SGA are accompanied by uncertainty about whether the infants actually suffer from intrauterine growth retardation. As we used a conservative definition of SGA (lower than two standard deviations below the mean), most if not all of our SGA infants are likely to have suffered from intrauterine growth retardation, whereas the AGA group may include some intrauterine growth retardation individuals who were less growth retarded.

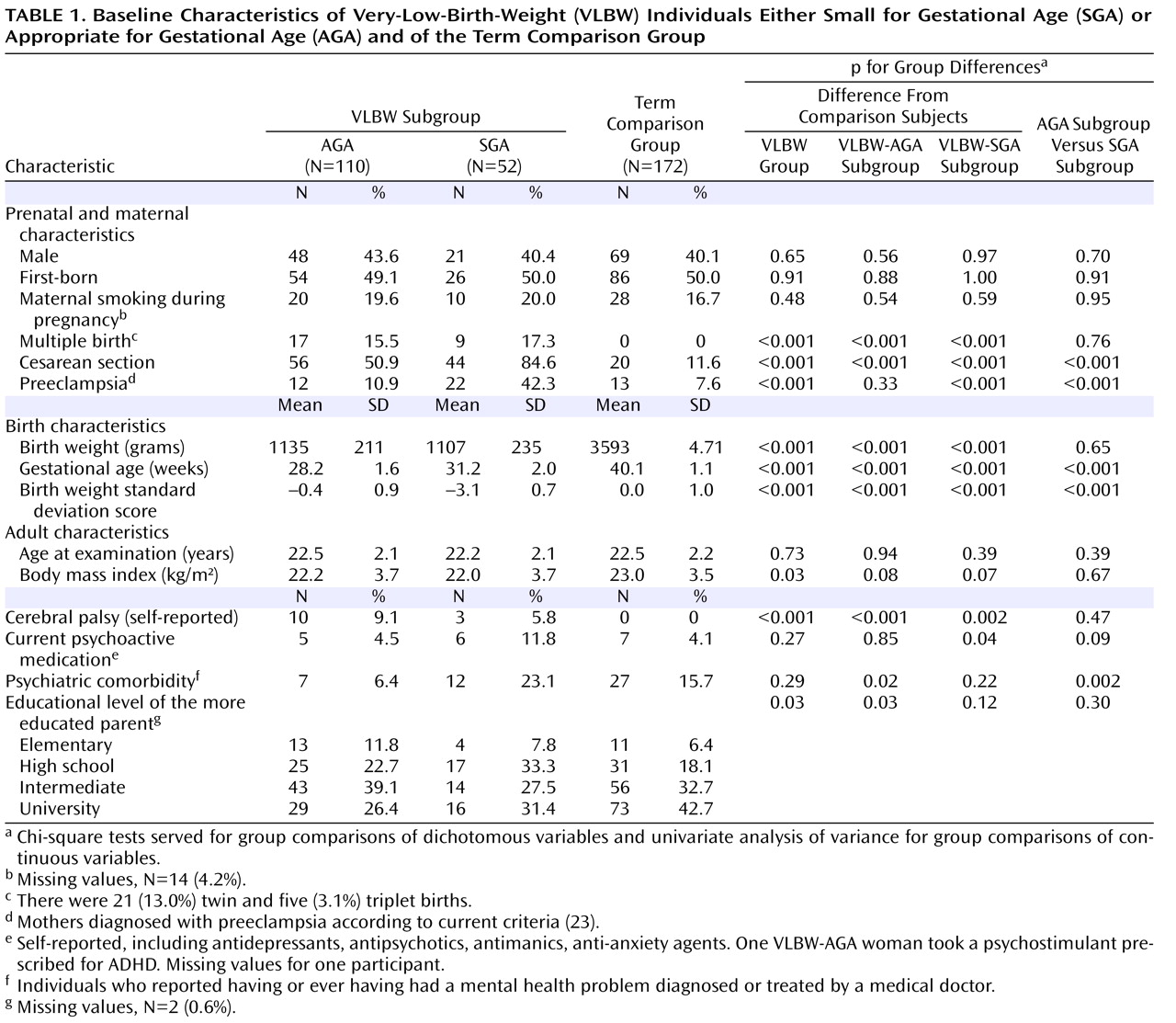

Our results must be considered in the light of some limitations. First, we aimed to assess ADHD-related behaviors, not make a clinical diagnosis. We therefore used a questionnaire, and questionnaires have proven to be important and helpful tools in the assessment of ADHD trends in population studies

(38,

39) . Fortunately, the APQ we used in this study was originally designed to assess ADHD-related behaviors in adulthood specifically

(25) . Since many ADHD questionnaires, as well as the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, were originally designed for children, new and different questionnaires are needed for assessing specifically adult ADHD. Second, we lack retrospective data on childhood ADHD, data needed according to the DSM-IV criteria for a valid diagnosis in adulthood. The validity of retrospective diagnoses has been questioned, however, because of susceptibility to recall bias

(40) . Third, as in similar study settings, a participation bias toward healthier participants cannot be ruled out, although our participants and nonparticipants did not differ with regard to most of the perinatal variables listed in

Table 1 . Fourth, since the participants were young adults themselves, we did not approach their parents and are therefore unable to adjust for possible genetic susceptibility indicated by any existing parental ADHD symptoms. Finally, the ADHD-related symptoms were assessed by self-report. When diagnosing ADHD in children, parent and teacher reports are considered more important than self-reports, whereas for adults, clinicians must rely to a greater extent on the patients’ subjective opinions of their own symptoms. Adults are rarely monitored by a parent or an employer as consistently as children are by their parents or teachers, making observer reports less accurate and self-reports of greater value

(25,

38) . Still, ADHD remains a clinical diagnosis

(38,

39), and studies of VLBW adults utilizing a more extensive assessment battery of ADHD remain to be done.

In sum, in contrast to previous findings in VLBW children, we found no evidence of increased behavioral symptoms of ADHD in VLBW adults. However, when we contrasted AGA and SGA subgroups with each other and with term comparison subjects, we found that the SGA group showed higher scores for executive dysfunction and emotional instability. Although these findings are reassuring for a large proportion of VLBW children and adults and their families, they also call for studies elucidating the pathophysiological and neuropsychological mechanisms underlying such differences.