In 1969, a psychiatric resident admitted a young woman who confessed to her doctor, “Twenty percent of the time I see reality, and the rest of the time I am in my dream world.” Six months later, near the end of her treatment with antipsychotic medications and psychotherapy, her resident summarized how he understood her illness:

There is no question that the psychosis continues.… Yet, within the overall personality there is … an ego-adaptive, coping, observing, trying to judge—albeit from a weak, uncertain and tenuous position … [often] overwhelmed in the face of inner chaos and psychosis. But there are islands of strength within the psychotic seas, and when the seas diminish, seemingly of their own accord, one can see these islands more clearly than ever before.… One can only wonder if all these islands are not somehow connected beneath the sea, and if so, how does one continue to raise the land mass, that is, capacity to cope and adapt above the level of the waters of the raging impulses of her psychosis.

Compare this record to one written nearly 40 years later at the same institution. Here, a psychiatric resident describes the hospital course of a man with the identical diagnosis as the woman:

This is a 25 yo Hispanic male with a past psych hx of schizophrenia who brought himself to the ER with the chief complaint of command AH telling him to hurt himself and hurt his brother.… Pt also endorsed depressed mood, decreased appetite, and insomnia. He did not have any other active SI or HI. Pt admitted that he had been off his psychotropic medications for the past 30 days.… Pt was restarted on his previous medications. On day 2, pt reported feeling improved after treatment. He denied having suicidal thoughts or homicidal thoughts. His AH frequency decreased. On day 3, pt reported improved mood, denied suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Case manager contacted the patient’s brother, who stated that pt did not get along with his family members and family members would not be willing to provide housing. The patient agreed to be discharged to a shelter.

The two patients experienced nearly identical troubles, including failure to live independently, a paucity of social relationships, and persistent psychosis. In the first case, the resident took little interest in the patient’s symptoms (despite the fact that antipsychotic medications had been in widespread use for 15 years) and spent many hours learning about her life outside the hospital and her inner psychological world. The second resident dearly cared about the patient’s symptoms and viewed them as unrelated to the scarcity and loneliness that characterized his social life. These divergent representations of the patient with schizophrenia reflect dramatic changes in the social, cultural, and scientific contexts in which psychiatry is practiced.

Much of what we do as clinicians is not a consequence of the natural world but, instead, results from our contingent social and cultural context and, as such, deserves critical scrutiny. Historical and anthropological approaches provide tools with which psychiatrists-in-training can reckon with the clinical challenges posed by a complex world. For the past 3 years, we have conducted a course on the social sciences and psychiatry for second-year psychiatric residents with these aims in mind. Through lectures, readings, and homework, the course engages residents in discussions about the psychiatric task. Social science is taught not as a set of abstract theories but as a set of tools to use as residents consider the responsibilities, complexities, and uncertainties of clinical work. The aim is to teach residents to critically engage the knowledge they use as psychiatrists and to make an intellectual investment in the future of their profession. In this article, we describe the course’s conceptual foundation, structure, and impact.

Course Rationale

The course asks residents to consider the fact that our sociocultural context is just as critical as basic neurobiology in shaping how we understand and intervene in our patients’ illnesses. Psychiatric training involves not only the mastery of basic facts

(1) but also a series of complex moral choices. The intraprofessional shifts reflected in the vignettes above present only one complexity of many. Today, entities outside the profession, such as the pharmaceutical industry and third-party payers, exert significant pressure on the structure of psychiatric work. Neuroscience and molecular biology carry such cultural cachet that they steal the limelight from the techniques of interpersonal caring that residents desperately want to learn. At the same time, neuroscientific advances (e.g., cognitive enhancement, surgically implantable long-term antipsychotic delivery systems) raise ethical challenges that psychiatrists have barely begun to confront

(2) . As a result, psychiatrists struggle against identities thrust upon them: neurologists of the brain, efficient billing machines, dispensers of wonder drugs, managers of the unmanageable.

By emphasizing that historical and cultural circumstances shape psychiatric work, the course is a partial antidote to the reductionist tendencies in biological psychiatry. Residents are often taught to see patients’ suffering as expressions of neurobiology gone awry. Instead, this course examines psychiatric illnesses as at once biological, cultural, and historical. Who is considered “sick” or “well” depends significantly on cultural views of normality and the nature of psychiatric institutions. As a man with schizophrenia told an anthropologist, “If I were living in the countryside, nobody would care about my solitude, but in the city, one is not allowed to live like a hermit” (

3, p. 39). Moreover, therapeutic truths in psychiatry are far from timeless. Residents can begin to see that how they evaluate mental illnesses, when they feel justified in intervening, and what form those interventions take are shaped by historical and social context.

The course allows residents to gain skills in cultural self-assessment

(4,

5) . Cultural self-assessment involves both seeing one’s self as situated in a particular social and historical moment and reflecting on the ways in which implicit norms and assumptions shape action. Culture is too often viewed as an attribute solely of the

other . Residents are keenly aware that direct-to-consumer advertisements from the pharmaceutical industry shape how patients think of their distress

(6), but they are less aware of how their own values shape their expectations for patients. By discussing concepts such as biological reductionism and social construction and by reviewing historical change, residents can see the cultural scaffolding that undergirds clinical thought and action. This awareness can prepare residents to think carefully about the meaning of their actions with patients.

Instructors

The course is designed and taught by the authors, psychiatrists trained as social scientists—one (J.T.B.) a historian with a focus on 20th-century psychiatric therapeutics, the other (E.B.) an anthropologist who examines contemporary psychiatric research practices. We draw from multiple social science fields in serving the overall objectives of the course, including psychological anthropology, medical anthropology, disability studies, the history and sociology of science, the social history of psychiatry, and mental health services. We emphasize the history of psychiatry in the United States and do not explicitly teach issues in cross-cultural psychiatry. Psychiatrists without graduate-level training but with expertise in some of these areas could craft a comparable course. For instance, we feature issues such as the gap between research and practice and equity in psychiatric care, not to present expert views but to further the aims of the course.

Course Goals

The goals of the course are for residents to:

Think actively about the process of becoming a psychiatrist

Recognize the historical and cultural roots of clinical tools

Learn basic concepts, including reductionism and social construction

Think critically about received wisdom in psychiatry

Gain curiosity about the lived experience of psychiatric illness

Modules of Instruction

In six to eight sessions, we cover four topics: becoming a psychiatrist, diagnosis, treatment, and illness experience. Each module is made up of topics addressed in class, teaching tools used in class, questions posed to residents during class, and homework that residents complete between classes. Homework assignments ask residents to note events during their week that pertain to the questions posed in class. A reader is distributed that includes articles and other materials for review in class (e.g., pages from DSM-I and DSM-II).

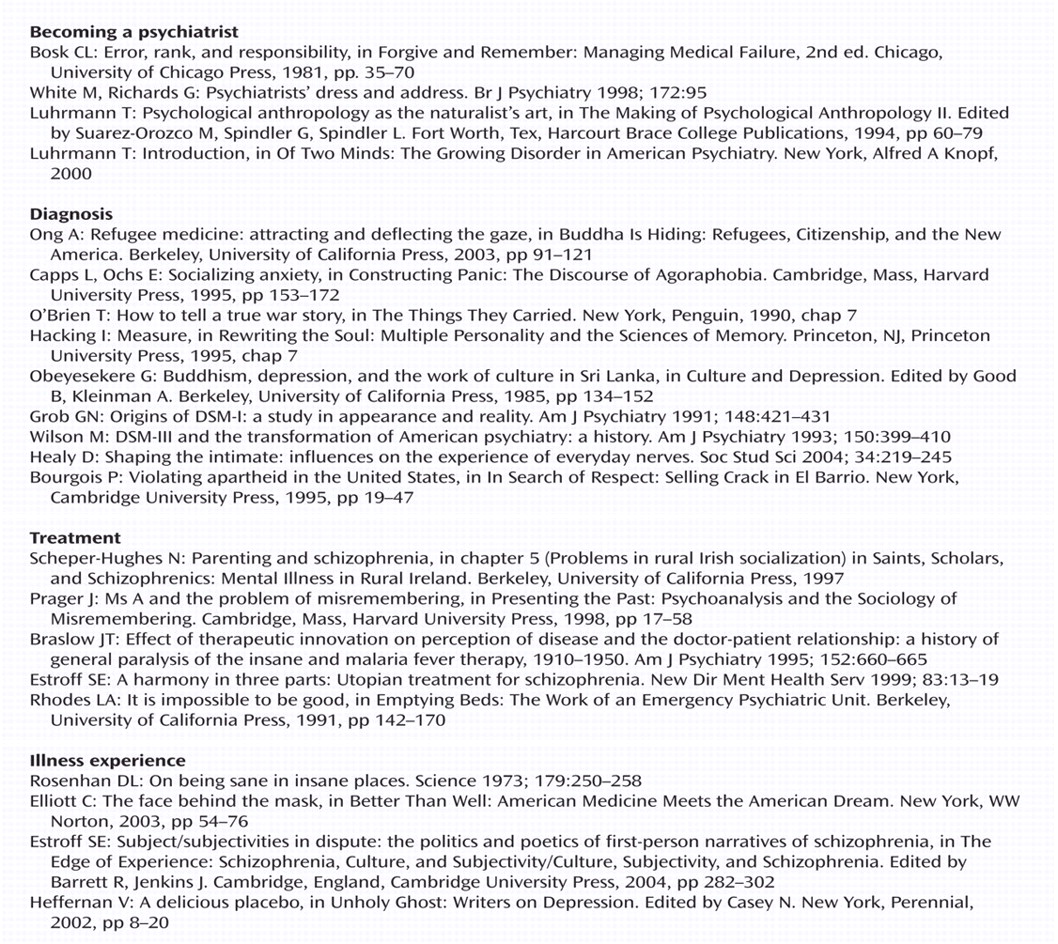

Figure 1 presents a sample syllabus. Residents rarely read the articles before class, but they are encouraged to keep and read them in time. Historical papers, patient records, and educational videotapes used in class are selected from a local resource, the UCLA Neuroscience History Archives.

Becoming a Psychiatrist

Topics

The module begins with a discussion of residency as a socialization process. Becoming a psychiatrist entails a shift in how one sees oneself and others. Models of psychopathology are not just information; they are theories of people. What one learns about the self and others extends beyond the workday. One becomes unable to ignore signs of hypomania in a store clerk or evidence of hallucinations in the odd neighbor. Introducing oneself at a party becomes awkward, as mere acquaintances disclose sensitive information or joke clumsily that psychiatrists can “read minds.” This new vision can be both exhilarating and burdensome

(7) . We disclose and discuss these changes openly.

Other discussion topics have included the emotional demands of the training process

(8) and common assumptions about psychiatrists. Residents have debated whether psychiatric curricula present two competing paradigms—the biological and the dynamic—or whether the two perspectives are complementary

(9) .

Tools

In the first session, each resident responds to the question “What did friends and family say when you told them you were going into psychiatry?” Common themes in residents’ stories are identified and used to explore assumptions about psychiatrists. Residents have raised the claim that psychiatrists are not “real” doctors; the public’s fascination with neuroscience; and other doctors’ idealization or devaluation of the psychiatric task (e.g., “I have such respect for anyone who could be a therapist” or “You are too smart to go into psychiatry”).

Research on physicians’ dress is reviewed to talk about authority and trust in psychiatric encounters

(10) . Residents read popular pieces that critique psychiatry, such as a recent opinion piece in the

Los Angeles Times with the provocative title “Psychiatry’s Sick Compulsion: Turning Weaknesses Into Diseases”

(11) . In exploring these views of psychiatry, we review the historical and cultural circumstances that may have promoted such conceptions.

Questions

What is a psychiatrist? What does a psychiatrist actually do? What will I lose in becoming a psychiatrist, and what will I gain? What do I say to respond to critics of psychiatry, or to those who idealize it?

Homework

Describe an attending you have worked with, and describe the ways he or she embodies the idea of a psychiatrist.

Diagnosis

Topics

One session is devoted to the history of concepts of psychiatric illnesses. We lecture on the multiple shifts in psychiatrists’ concepts of schizophrenia in the past century and on changes in concepts of depression in the past 30 years

(12) . A historical overview of the creation of clinical tools, such as DSM and rating scales, emphasizes that these clinical tools are a product of a history and are subject to contemporary forces that stabilize their use. Labeling theory is presented

(13) in order to discuss how diagnostic labels affect patients’ perceptions of themselves

(14) . Topics include the fact that some diagnoses can irreversibly alter one’s sense of self (“schizophrenia, paranoid type” or “borderline personality disorder”), while other diagnoses function merely to facilitate communication and standardize clinical work (“anxiety disorder not otherwise specified”).

Diagnosis is discussed as an act of reductionism. Diagnostic schema are reductionistic because they allow one to comprehend complex phenomena (e.g., experience) by attending to a set of simpler phenomena (e.g., criteria). Reductionism is discussed because it is an indispensable methodological tool, but also because complex phenomena such as human suffering may be inherently irreducible

(15,

16) . Biological reductionism and its underlying assumptions are reviewed. Strict biological reductionistic theories consider mental illness to be a direct manifestation of a disordered brain; social and psychological circumstances are not seen to have an impact on the course or nature of the illness

(17) . We use the example of schizophrenia to debate whether biological models of mental illness allow clinicians to imagine that their patients’ life experiences are less complex than their own, as some contend

(17) .

Tools

Excerpts from DSM-I (1952) and DSM-II (1968) are contrasted with contemporary diagnostic schema. Physicians’ narratives from patient records from the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s demonstrate changes in doctors’ views of patients. Pharmaceutical advertisements are used to evocatively demonstrate the same shifts, such as an advertisement for Valium from 1970 entitled “35 and single,” that present clinical concepts that residents recognize as anachronistic

(18) . We review data on social causation pathways for schizophrenia

(19) .

Questions

How do the diagnostic tools I use change how I view my patients? What function do patient labels serve (“very axis II,” “chronic schizophrenia,” “substance abuser”)? How do ideas about the biological causality of certain phenomena change how I listen to my patients?

Homework

Provide a clinical example of “reductionism.” For instance, which frameworks do you use to organize data about a patient? What other organizational framework could you use? What influences your choice of one framework over another?

Treatment

Topics

We emphasize the historical and social context of treatment development in psychiatry. Lecture topics have included the use of amphetamines in children in the 1930s

(20), the development of thorazine, the adoption of clinical trials in psychiatric research, and the historical role of psychoanalysis in schizophrenia

(21) . The dependence of drug discovery on clinical work is emphasized: treatment modalities in psychiatry have often been linked as tightly to clinical contexts as to research findings. We lecture on the history of lobotomy to demonstrate that it was neither a fringe procedure nor perceived as barbaric; professional thought leaders (and a Nobel Prize winner) promulgated its usefulness. At the same time, the context of state hospital care shaped the use of the intervention

(22,

23) . The history of psychiatric treatment can demonstrate to residents that since today’s interventions are supported by today’s norms, some trusted practices may seem irresponsible to future psychiatrists. By emphasizing that what the profession considers “best” and “true” will change during the course of residents’ careers, the discussions prepare residents for engaged learning in years to come.

We discuss the practice relevance of contemporary psychiatric research. Residents are asked to consider what basic science constructs mean for their patients

(24) and to consider how they will use evidence in practice. Treatment researchers define clinical targets using laboratory-based measurement techniques, but research constructs are rarely comparable to patient-care scenarios

(25) . Residents are asked to interpret the utility of complex findings. Would impairment in semantic priming in schizophrenia, as measured by N400 event-related potentials

(26), change how they communicate with patients? Should the “failure of frontolimbic inhibitory function” (

27, p. 1840) in individuals with borderline personality disorder change clinical decision making? When should clinical trials, despite their carefully selected subject pools and structured outcome measures, change prescribing practices

(28) ? Residents are encouraged to ask these questions of themselves, of attendings, and of researchers and to imagine what practice-relevant research might look like.

Tools

Patient records reveal the logic that leads providers to choose one treatment over another. Research from earlier decades, such as treatment trials from the 1930s

(29), demonstrates shifts in scientific standards. A recent issue of the

American Journal of Psychiatry is reviewed, and each resident justifies what one should take away from each article.

Questions

How did I decide that certain facts were important to know? What influences our knowledge base (pharmaceutical company priorities, excitement about new technologies, reimbursement structures)?

Homework

Bring an example of an assumption disguised as a fact. Collect impressions reported by attendings as if they were true or clinical advice described as factual that you suspect may not be so well understood (“olanzapine is more effective for negative symptoms than other antipsychotics, so I’d choose that one”).

Illness Experience

Topics

First-person or ethnographic accounts of experiences of mental illness including depression

(30), schizophrenia

(31), and mental retardation are reviewed

(32,

33) . These accounts highlight the heterogeneity of mental illness experience, and they describe outcomes in a comprehensive narrative. Texts on illness experience remind residents that they see an extremely brief slice of an individual’s life in the clinic. We review research models in which the experience of illness guides mental health research. Claims that patients’ limited voice in research results in a “representational gap”

(34) in mental health studies

(35) are debated. Residents consider possibilities for patient engagement in research

(36) .

Social constructionism is reviewed in this context. Unfortunately, social constructionism is too often equated with a set of radical propositions that have little merit for mental health providers, such as the notion that mental illnesses are constructed categories deployed to maintain social order, or that psychosis is a form of political liberation. We neither subscribe to these radical versions of social constructionism nor teach them because they do not help clinicians think about patients. Instead, social construction is discussed as the idea that social configurations alter what counts as illness and health and that social circumstances shape illness experience. We discuss a study from the 1970s in which healthy individuals admitted to psychiatric units were viewed as ill despite their normal behavior; context can shape our evaluations of others

(37) . Residents discuss whether the results would be replicated today. Aspects of American culture that determine the line dividing the ill from the well

(38) are also discussed.

Tools

A mock board game called “Mental Patient”

(39, pp. 148–152) and firsthand accounts

(40) demonstrate the impact of institutionalization on identity. A syllabus of firsthand and ethnographic accounts is provided.

Questions

How can experience be captured with phenomenological or symptomatological schema? What role does our expertise play when we do not and cannot know what it is like to have a severe mental illness? How and why do I work with patients who do not want my help?

Homework

Identify some assumptions held by inpatient staff about patients’ lives outside the hospital. Explain what function these assumptions serve for staff (e.g., diffusing stress).

Response to the Course

The course is relatively new. While it has been well received, a systematic evaluation should be conducted to assess whether the course leads to changes in attitudes toward diagnosis and treatment; in concepts of patients; in learning habits; and in clinical and ethical decision making.

A few preliminary observations are worth noting. Residents in their second postgraduate year (PGY-2) respond actively to the course. Adjustment to a new role, the position of psychiatry within medicine, and the construction of knowledge concern them daily. Modules 2 and 3 may be best taught to PGY-3 residents, who have more experience in treatment and diagnosis. The curriculum could be useful for residents at any stage, but discussions may vary considerably.

The course requires protected lecture time. Time pressure or interruptions (e.g., pages) impede discussions, and full attendance facilitates communication. Because it encourages residents to respond to one another, the course can become a site for expression of shared complaints. Some of these discussions are pursued, as they further the objectives of the course. For instance, a discussion of patients’ experiences of institutionalization once elicited residents’ feelings that they too are “worker bees” on the unit, “locked in” and “on a leash.” On another occasion, residents expressed frustration that patients underestimate how much effort they exert caring for them. Feeling undervalued was discussed as an experience of residents and patients.

The course can be emotionally stimulating. As residents learn to master a new set of skills, the course asks them to recognize uncertainty within the knowledge base. The skills psychiatrists no longer gain—in psychosocial treatments or psychoanalysis—can trouble residents, especially those working on short-stay inpatient units. The fact that well-meaning psychiatrists in past decades used treatments such as lobotomy can also trouble residents, leading some to worry about the unknown side effects of current treatments. The question of the appropriate role for critique is discussed. We emphasize the inherent value of what psychiatrists do and the humanity of psychiatric work. On balance, the course generates a healthy skepticism that enlivens rather than detracts from clinical work.

Previous iterations of this course have generated less enthusiasm when taught by nonpsychiatrist social scientists. If an instructor lacks firsthand experience of the physical and intellectual demands of residency, or if the instructor is accustomed to teaching graduate students who crave reading and debate, residents can appear disengaged. In contrast, clinician-researchers from the social sciences can characterize social science issues (e.g., reductionism) as relevant to the daily life of a resident (e.g., within the diagnostic interview). We draw heavily on our own experiences as trainees to make abstract concepts concrete and resonant.

Conclusions

Exposure to the social sciences of psychiatry can teach residents to critically assess the psychiatric knowledge base, attend to the role of social factors in shaping psychiatric illness and treatment, and question their own assumptions about what is best to do for patients. Learning that therapeutic truths in psychiatry change over time and that clinical tools such as the DSM are products of a particular intellectual and social history can help residents take responsibility for the knowledge they put into action. The course can also help residents reckon with the complexity of becoming a psychiatrist today.