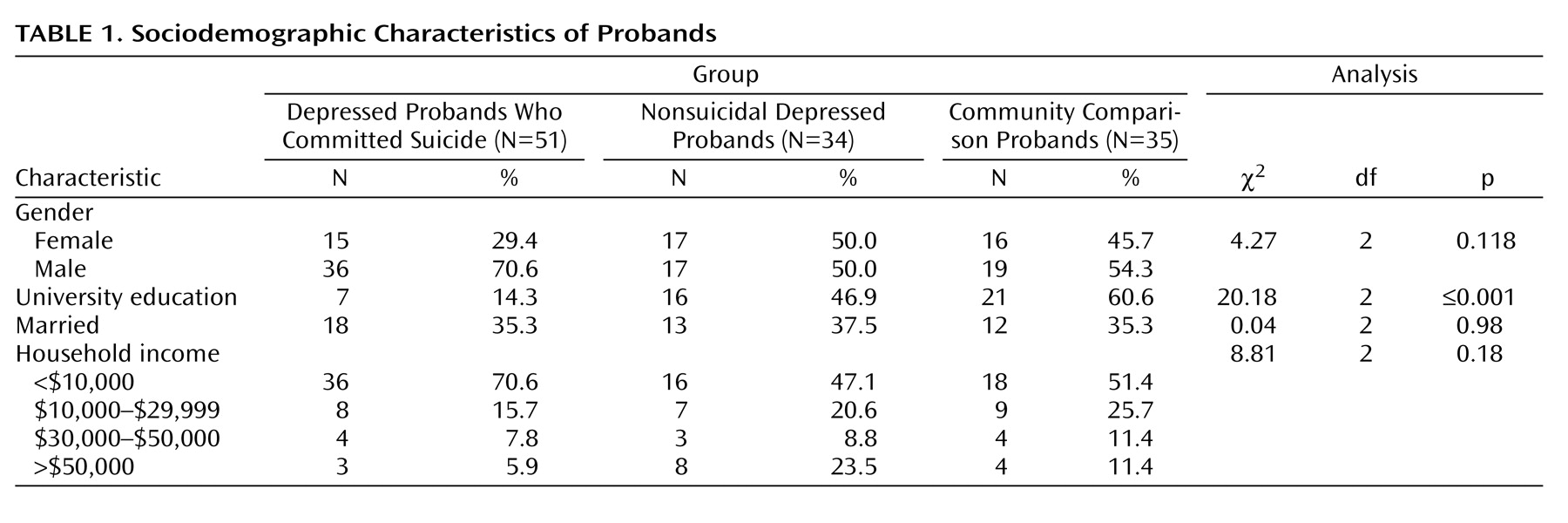

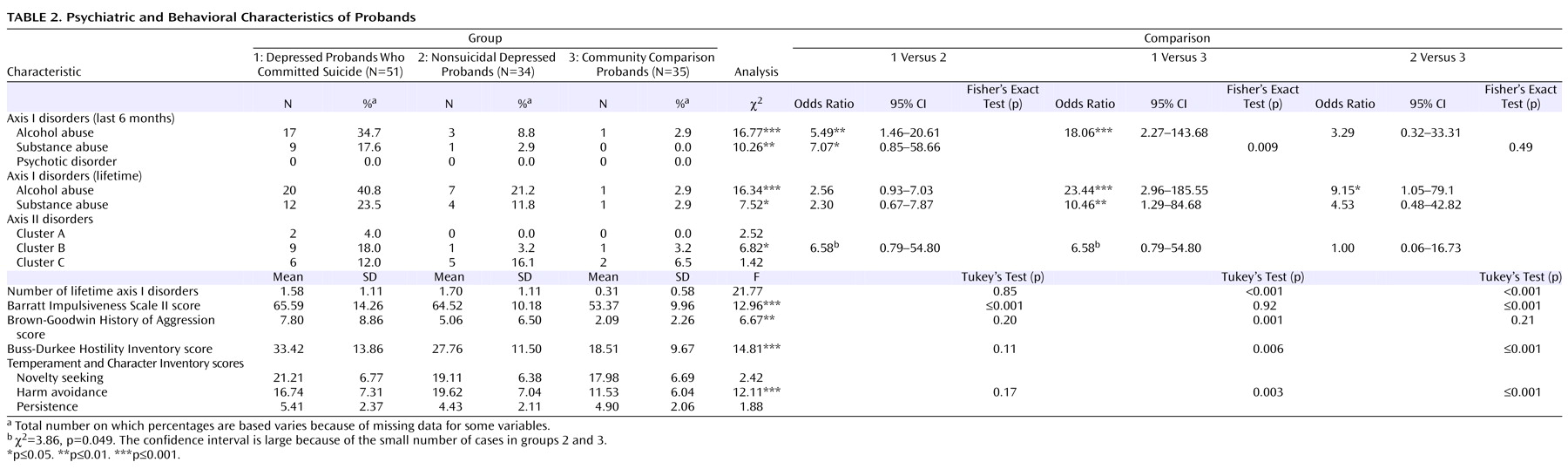

With respect to current (past 6 months) axis I psychopathology, as expected

(12,

13), depressed probands who committed suicide were more likely to have met criteria for alcohol abuse and illicit substance abuse than nonsuicidal depressed probands and community comparison probands (

Table 2 ). Depressed probands who committed suicide were also more likely than community comparison probands, but not nonsuicidal depressed probands, to have met criteria for lifetime alcohol abuse and illicit substance abuse. Further, comorbidity with cluster B personality pathology was more common among depressed probands who committed suicide.

Personality trait comparisons revealed differences in scores for the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, Brown-Goodwin History of Aggression, Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, and harm avoidance subscale of the Temperament and Character Inventory. Tukey’s post hoc comparisons showed that depressed probands who committed suicide and nonsuicidal depressed probands had higher scores than community comparison probands on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, and harm avoidance subscale of the Temperament and Character Inventory, but no significant differences were found between depressed probands who committed suicide and nonsuicidal depressed probands. Post hoc tests also revealed higher scores for the Brown-Goodwin History of Aggression among depressed probands who committed suicide relative to community comparison probands. No other group differences were seen.

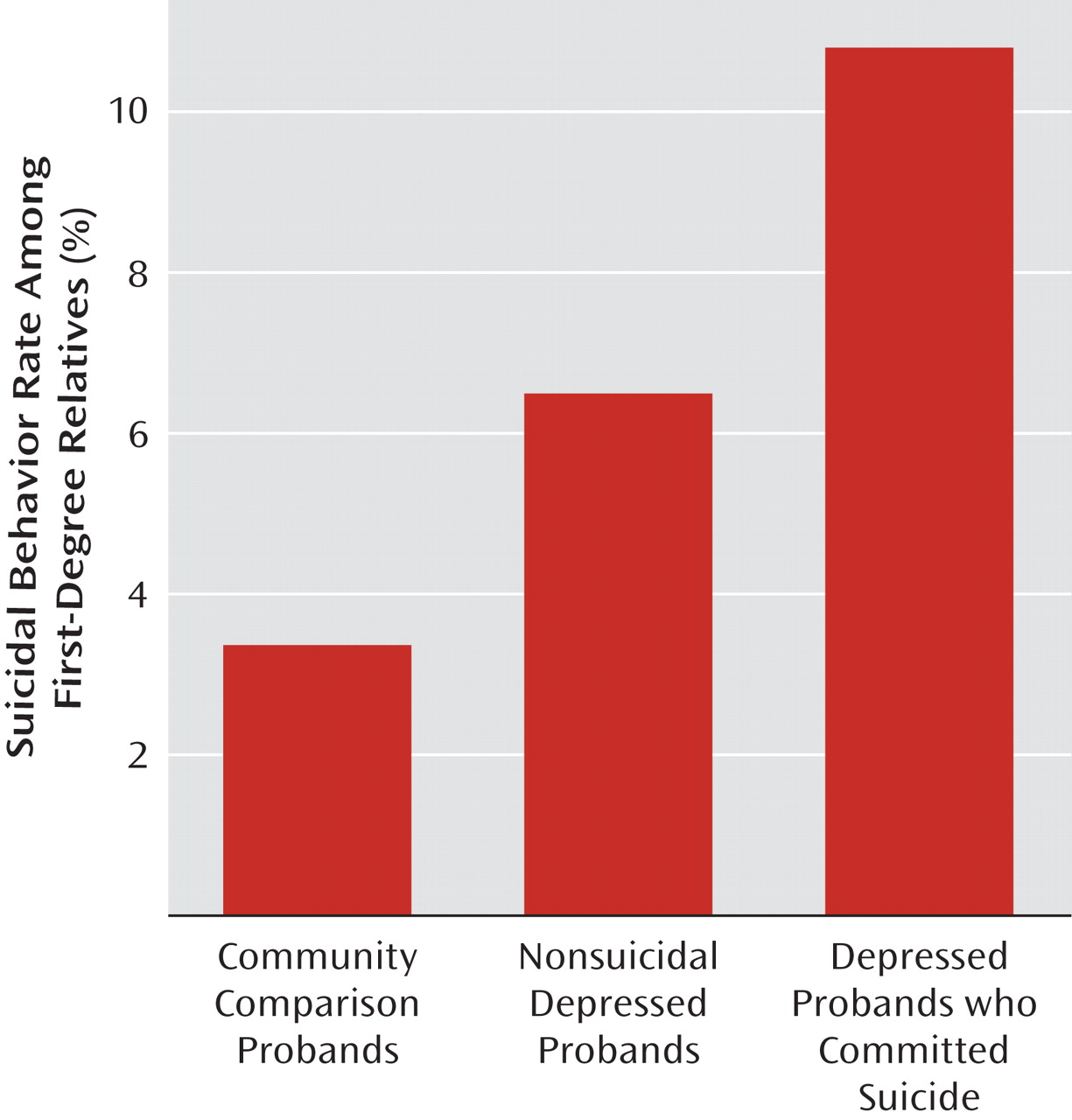

Suicidal Behavior Among Relatives

With respect to lethal suicidal behavior, among first-degree relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide, nonsuicidal depressed probands, and community comparison probands, 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.0%, respectively, died by suicide. When lethal and nonlethal suicidal behaviors were combined, the respective rates rose to 10.8%, 6.5%, and 3.4% (χ

2 =11.57, df=2, p≤0.01 [

Figure 1 ]).

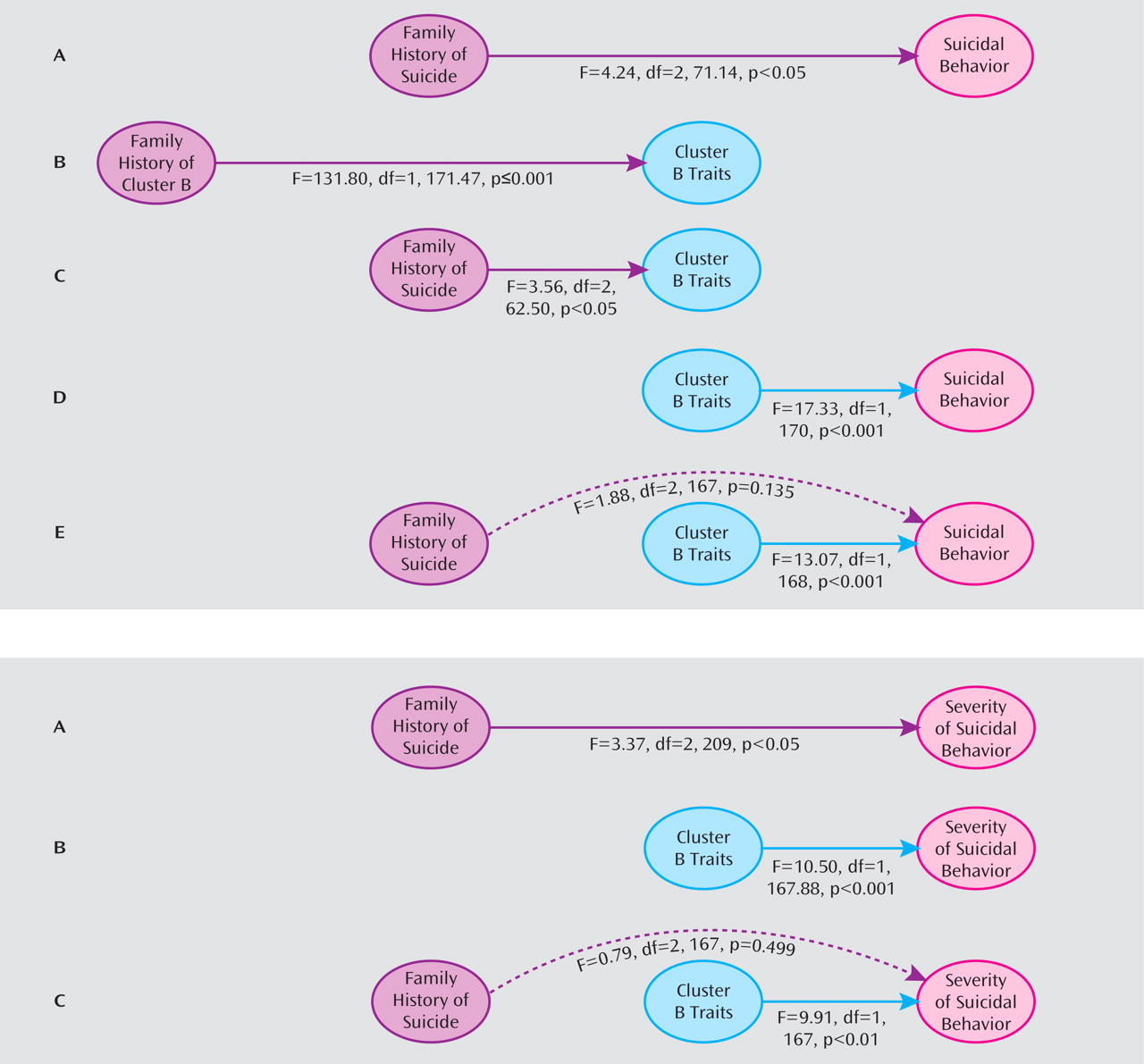

We tested the relationship between family history (three-group definition) and recurrence of suicidal behavior among directly assessed relatives. We also examined random effects for members of the same family and controlled for age. This model received significant contributions from family history (F=4.24, df=2, 71.14, p<0.05) and the intercept (F=9.73, df=1, 170.10, p<0.01) and a tendency for age (F=3.63, df=1, 171.33, p=0.06), suggesting independence of liability after accounting for the nonindependence of data. Pairwise least significant difference group-estimate comparisons revealed significant differences between relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands (p=0.03) as well as between relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and community comparison probands (p=0.01), but not between relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands and community comparison probands (p=0.88).

Similarly, we tested this relationship with respect to the medical severity of suicide attempts and found contributions from family history (F=3.37, df=2, 209, p<0.05) and the intercept (F=4.18, df=1, 209, p<0.05) but not age. Pairwise least significant difference group-estimate comparisons revealed significant differences for severity of suicidal behavior between relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands (mean difference=4.00 [SD=2.02], p≤0.05) as well as between relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and community comparison probands (mean difference=4.48 [SD=1.94], p<0.05), but not between relatives of nonsuicidal depressed and community comparison probands (mean difference=0.48 [SD=2.21]).

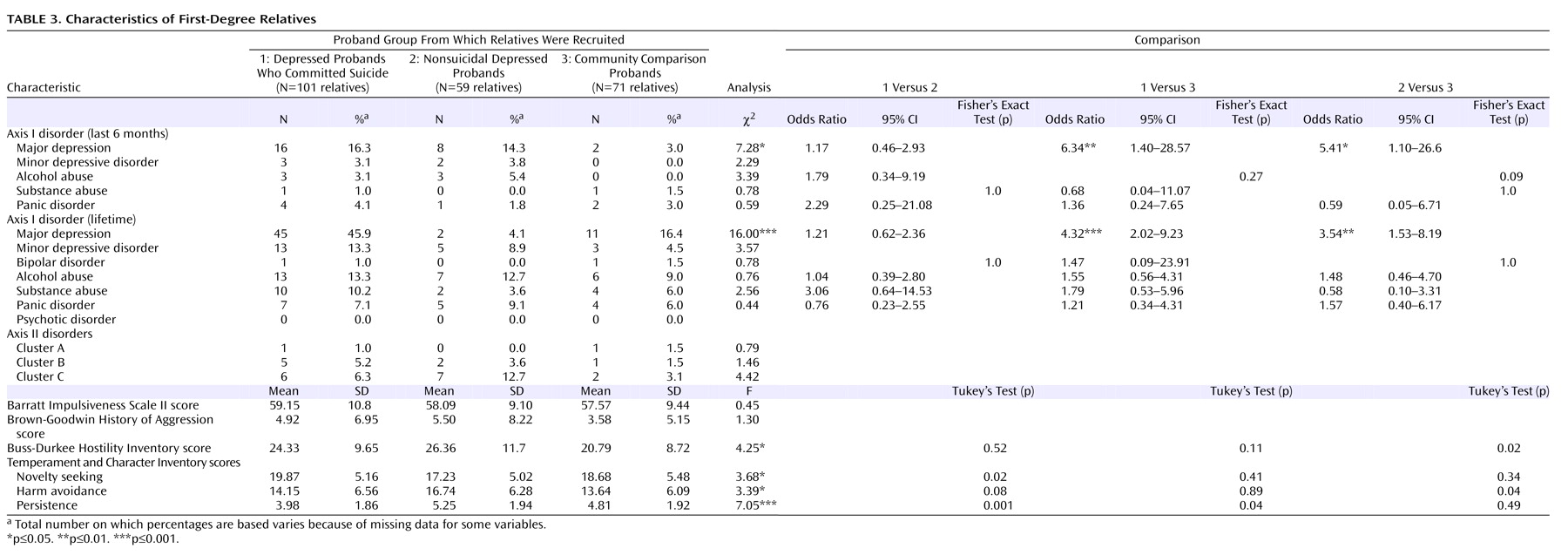

Relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and nonsuicidal depressed probands were more likely than relatives of community comparison probands to meet criteria for current and lifetime major depressive disorder (

Table 3 ). No other axis I or II characteristics significantly differentiated these two groups. Differences between indirectly assessed relatives followed the same pattern (data not shown).

With respect to personality-trait characteristics, significant differences were observed for the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory score and the harm avoidance, novelty seeking, and persistence subscale scores from the Temperament and Character Inventory. Tukey’s post hoc comparisons revealed that relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide had higher novelty seeking scores than relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands and lower persistence scores than both nonsuicidal depressed probands and community comparison probands (

Table 3 ). Relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands had higher Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory and harm avoidance scores than relatives of community comparison probands (p<0.05). No other post hoc comparisons reached significance.

Cluster B Traits as Intermediate Phenotypes of Suicide

Commonly studied aspects of impulsive aggression are impulsivity, hostility, and aggression. Cluster B personality disorders can be considered pathological manifestations of these traits

(50) . Measures of impulsive aggression relate to a superordinate category

(51), and, accordingly, twin studies suggest a common genetic effect for cluster B personality disorders

(52) . Our studies in suicide completion highlight the interaction between impulsive and aggressive traits in increased risk for suicide, even after accounting for main effects

(25) . To represent the co-occurrence of impulsive and aggressive traits, we created a measure representing the latent construct of impulsive aggression/cluster B traits. Using factor analysis to create an aggregate measure of cluster B traits, a single factor emerged, with an eigenvalue of 2.91 and component loadings of 0.68 (cluster B disorders), 0.74 (Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory), 0.78 (Brown-Goodwin History of Aggression), and 0.73 (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale).

We hypothesized that impulsive-aggressive behavior and cluster B traits would function as intermediate phenotypes, also called endophenotypes, and mediate familial aggregation of suicide. Our test of cluster B traits as an endophenotype of suicide followed the criteria outlined by Gottesman and Gould

(48) . The approach and results from these analyses are illustrated in

Figure 2 .

Prevalence among probands

We used one-way ANOVA to determine whether the aggregate measure differentiated the proband groups (depressed probands who committed suicide: 0.77 [SD=1.43]; nonsuicidal depressed probands: 0.16 [SD=0.79]; community comparison probands: –0.57 [SD=0.67]; F=13.90, df=2, 98, p≤0.001). Tukey’s post hoc tests revealed a difference between depressed probands who committed suicide and nonsuicidal depressed probands approaching significance (p=0.06) and significant differences between community comparison probands and depressed probands who committed suicide (p≤0.001) and nonsuicidal depressed probands (p<0.05). We therefore observed a gradient of cluster B traits, with probands who committed suicide exhibiting higher levels of these traits than community comparison probands.

Association with family predisposition to suicide

We aimed to determine whether a familial predisposition to suicide was associated with increased levels of cluster B traits in first-degree relatives. In predicting cluster B traits, we found significant contributions from family history (F=3.56, df=2, 62.50, p<0.05), age (F=15.17, df=1, 174.36, p≤0.001), and the intercept (F=8.06, df=1, 166.77, p<0.01). Estimated means for cluster B traits were as follows: relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide, 0.03 (95% CI=–0.18 to 0.24); relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands, –0.09 (95% CI=–0.35 to 0.15); and relatives of community comparison probands, –0.40 (95% CI=–0.65 to –0.15). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and relatives of community comparison probands (p=0.01), but not relatives of depressed probands who committed suicide and relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands or relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands and relatives of community comparison probands.

Re-evaluating the model with relatives of nonsuicidal depressed probands and community comparison probands combined revealed significant contributions from family history (F=4.03, df=1, 63.82, p<0.05), age (F=12.75, df=1, 176.75, p£0.001), and the intercept (F=7.34, df=1, 170.81, p<0.01). Estimated means for cluster B traits were as follows: positive family history, 0.02 (95% CI=–0.18 to 0.24); negative family history, –0.25 (95% CI=–0.43 to –0.07).

Thus, familial predisposition to suicide was associated with increased cluster B traits, although the effect was less pronounced with the three-group definition.

Are cluster B traits familial?

We next tested whether cluster B traits were themselves familial by predicting the aggregate cluster B trait measure as a function of diagnostic criteria for cluster B disorders among index subjects. This model did not include familial predisposition to suicide. Significant contributions to the model were from the absence or presence of cluster B disorders among index subjects (F=131.80, df=1, 171.47, p≤0.001), age (F=14.70, df=1, 176.05, p≤0.001), and the intercept (F=91.55, df=1, 175.74, p≤0.001). The estimated trait mean for relatives of probands who met criteria for cluster B personality disorders was 2.67 (95% CI=2.18 to 3.17), and the estimated trait mean for relatives of probands who did not meet criteria for these disorders was –0.23 (95% CI=–0.34 to –0.13). Thus, cluster B traits demonstrated familial loading.

Association with recurrence of suicidal behavior in relatives

To test whether the cluster B aggregate was associated with recurrence of suicidal behavior in relatives, we evaluated a model predicting recurrence of suicidal behavior among relatives and included the aggregate and age. The intercept did not significantly contribute to the model, and thus it was removed and the model re-evaluated. The final model received contributions from cluster B traits (F=17.33, df=1, 170, p≤0.001) and age (F=20.39, df=1, 170, p≤0.001). Fixed-effects estimates revealed a positive association between the cluster B aggregate and suicide attempts (0.10, 95% CI=0.05–0.15; t=4.16, df=170, p≤0.001).

Mediating familial predisposition

To evaluate mediation, we followed Baron and Kenny’s

(49) criteria. In predicting recurrence of suicidal behavior among relatives, we included family history, the cluster B aggregate, and age. The intercept did not significantly contribute to the model and was removed prior to reporting final effects. The model revealed a significant effect for cluster B traits (F=13.07, df=1, 167, p≤0.001), but not age, and a large decrease in effect for familial predisposition to suicide that no longer significantly contributed to the model was found (F=1.88, df=2, 167, p=0.14). Estimates revealed that increased cluster B traits were associated with suicidal behavior (0.09, 95% CI=0.04–0.14; t=3.67, df=168, p≤0.001), suggesting that cluster B traits act as intermediate phenotypes accounting for a portion of the familial vulnerability to suicide.