This article focuses on PROSPECT’s primary outcomes during the second year of treatment. We test the hypotheses that depressed patients treated in practices offering the PROSPECT intervention have a greater reduction in suicidal ideation and that they have better depression outcomes—that is, a greater decline in depressive symptoms and higher rates of treatment response and remission—than patients treated in practices delivering usual care over 2 years.

Discussion

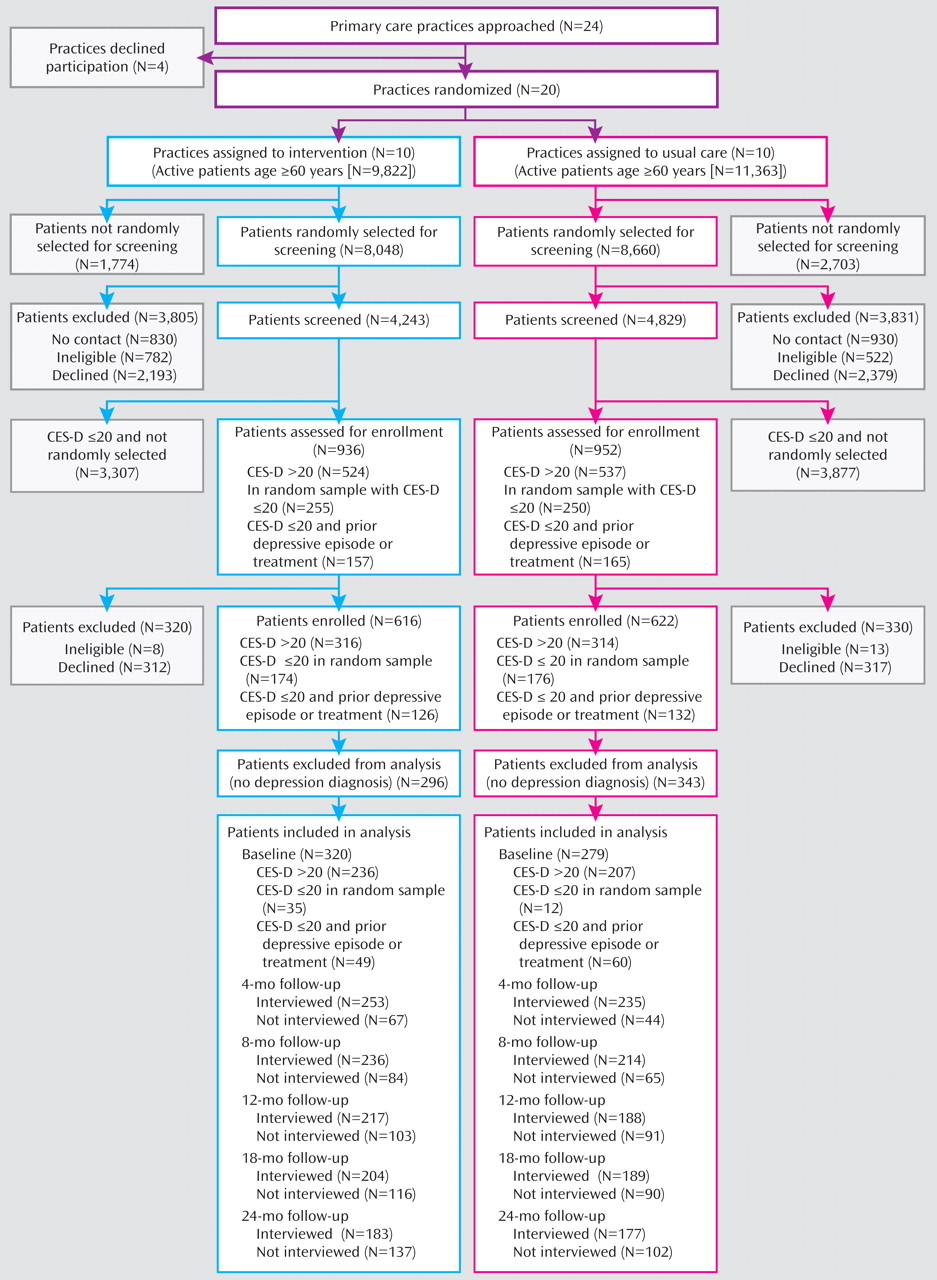

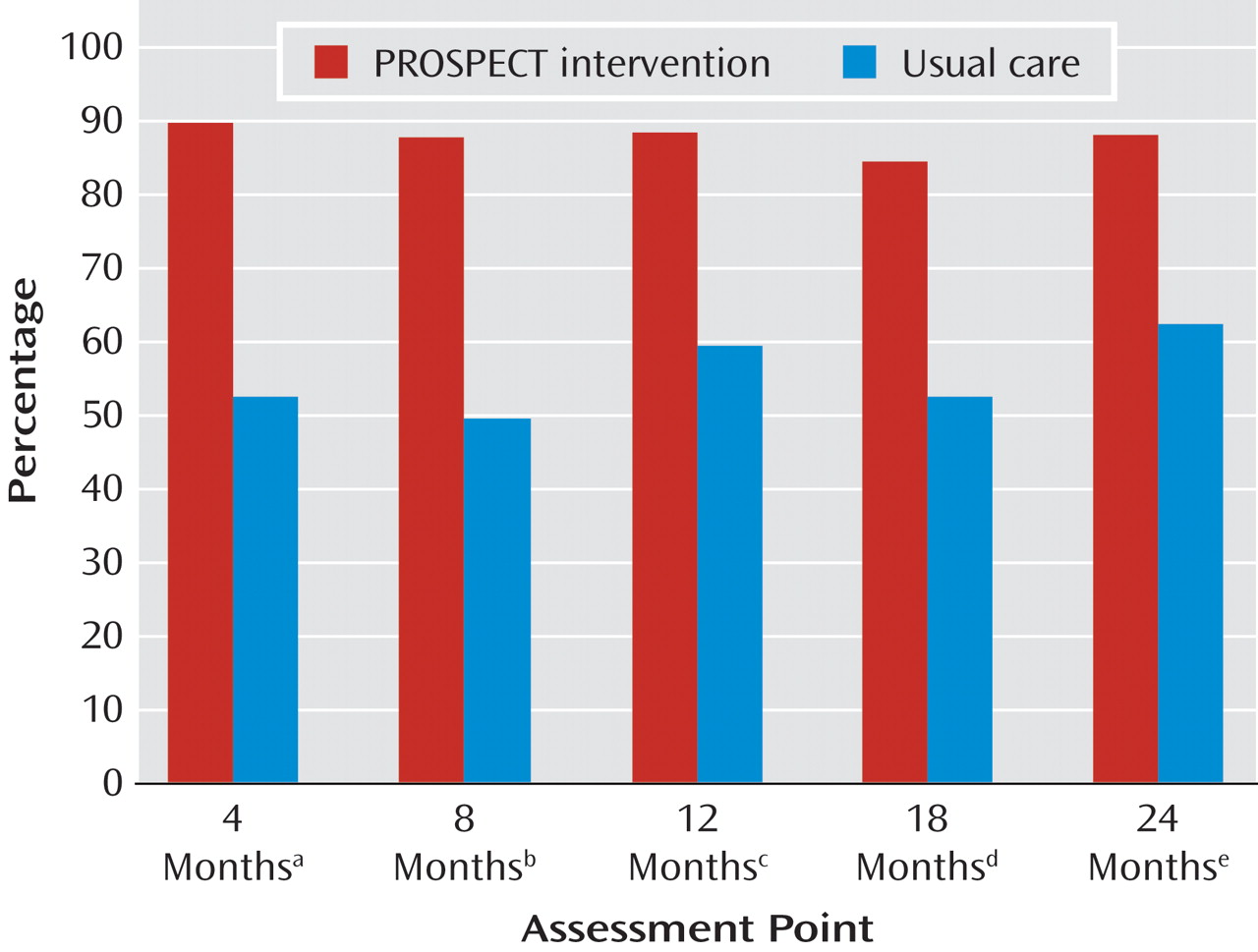

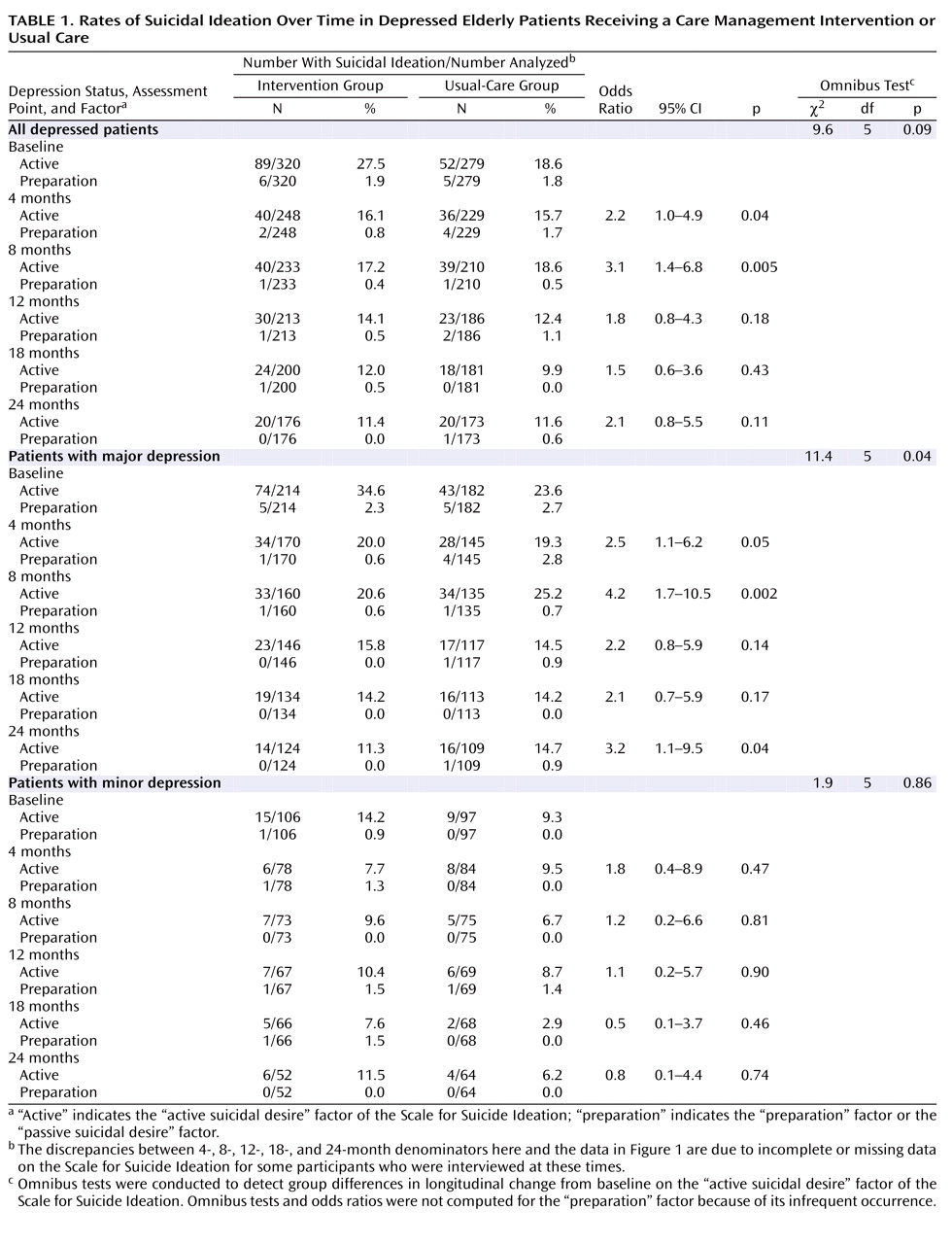

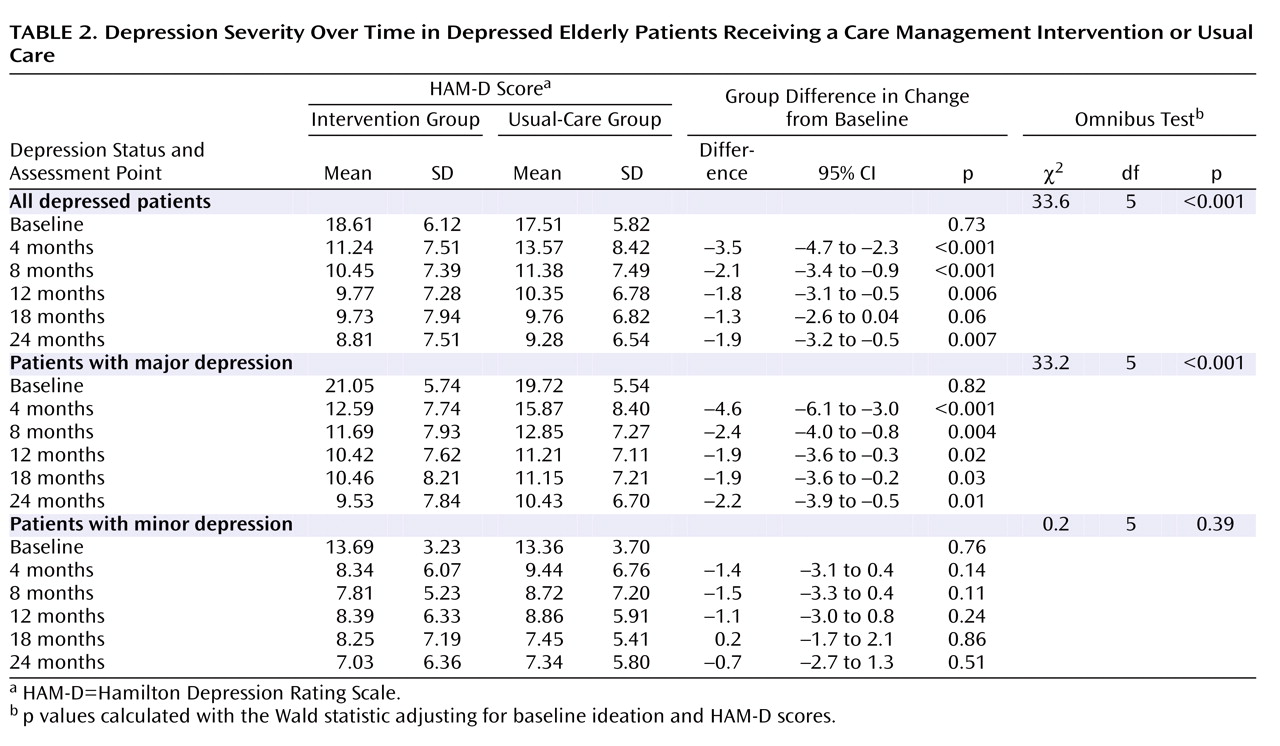

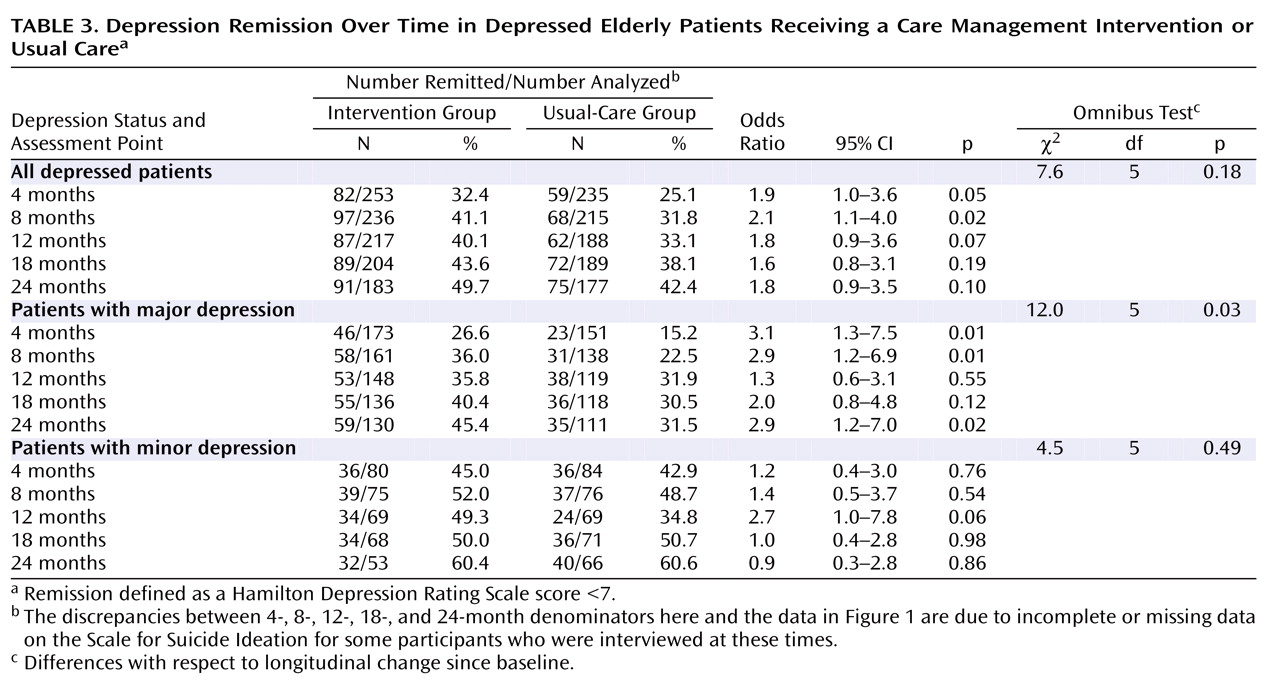

The principal finding of this study is that depressed patients in the practices that were randomly assigned to use the PROSPECT intervention had a higher likelihood of receiving treatment for depression, a greater decline in suicidal ideation, lower severity of depressive symptoms, and a higher response rate over 24 months than patients in practices providing usual care. At any assessment point, 84.9%–89% of patients in the intervention group received antidepressants and/or psychotherapy, while only 49%–62% of patients in the usual-care group were treated for depression. The intervention was most effective in reducing suicidal ideation among patients with major depression. The decline was sharpest in the first 4 months, and suicidal ideation remained low up to 24 months. Similarly, severity of depression remained lower in patients in the intervention group than in the usual-care group throughout the 24 months. Among patients with major depression, a greater number achieved remission in the intervention than the usual-care group at 4, 8, and 24 months. The intervention had no advantages among patients with minor depression.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of depression care management focusing on suicidal ideation and depressive psychopathology in older primary care patients over a 24-month period. Its findings are consistent with observations in mixed-aged primary care patients

(18), including an intervention of 24 months duration

(19) . In geriatric patients, the Improving Mood–Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study provided access to a depression care manager for up to 12 months

(20) . Primary care patients receiving the IMPACT intervention were more likely to receive treatment for depression than patients receiving usual care and had better depression outcomes. The advantage over usual care was retained 12 months after the end of the intervention, although there was a decline in response and remission rates from month 12 to month 24

(21) . In contrast, with continuing depression care management the response and remission rates in the intervention arm of the PROSPECT study remained high or increased.

In most participants, suicidal ideation was passive, as is often the case in depressed primary care patients

(22) . Even passive suicidal ideation requires attention and treatment. Depressed elders with passive suicidal ideation are more likely to have a history of suicide attempts, higher scores on hopelessness

(23), slower treatment response, and lower rates of response than nonsuicidal elders with major depression

(24) . Passive suicidal ideation has a stronger association with medical comorbidity and service utilization than active suicidal ideation or no suicidal ideation

(5) . Finally, 35% of patients with suicidal ideation change ideation status during the index episode; patients with passive ideation develop active ideation, and patients with active ideation shift to passive ideation

(23) . Change over time in passive suicidal ideation requires further research to identify treatment-responsive and treatment-resistant components that may further focus suicide prevention interventions for depressed older primary care patients.

There were two suicide attempts in the intervention group (one of them completed) and three in the usual-care group. These numbers do not allow statistical study of the relationship of suicidal ideation to suicide or attempts, but they underscore the challenge of reducing the risk of suicide in primary care settings. The relationship of reduction in the rate of suicidal ideation, and especially passive or death ideation, to suicide remains to be determined.

Over the 24-month study period, 49.7% of depressed patients in the intervention group achieved remission (HAM-D score <7). Remission, defined as an almost asymptomatic state, is the optimal outcome because it is associated with a low relapse rate and high functioning

(25) . Randomized acute antidepressant trials have shown that 30%–40% of patients achieve remission

(26) . A controlled maintenance treatment trial found that 65% of elderly patients with major depression remained in remission over 24 months while treated with paroxetine and monthly psychotherapy

(27) . The remission rate of the PROSPECT intervention was somewhat lower than this figure. Nonetheless, demonstrating that a care management intervention can maintain almost half of depressed primary care patients in remission is evidence of a meaningful level of effectiveness.

While antidepressant prescriptions have been rising, many depressed primary care patients receive no treatment for depression

(19) . Poor treatment adherence further compromises their care

(28) . In this study, more than 84% of patients in the intervention group received antidepressants or psychotherapy throughout the study, while only 49%–62% of those in the usual-care group received any treatment for depression.

Depression almost doubles the risk of death in community samples

(29) . Patients with major depression who received the PROSPECT intervention had a lower mortality rate than those who received usual care (adjusted hazard ratio=0.55, 95% CI=0.36–0.84) over a median follow-up period of 52.8 months

(17), but there were no differences in mortality among patients with minor depression. This observation is consistent with reduced all-cause mortality reported in patients receiving antidepressants over 40 months in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) study

(30) .

The benefits of the PROSPECT intervention on suicidal ideation and on depression were limited to patients with major depression. Patients with minor depression had overall favorable outcomes regardless of treatment assignment. At 24 months, only 6.2% of patients in the usual-care group had any suicidal ideation and 60.6% had achieved remission of minor depression. Given limited resources, patients with major depression should be the target of a care management intervention.

Limitations of the study include the use of Scale for Suicide Ideation as the sole method for ascertaining suicidal ideation, the lack of information on participants’ discrete medical problems, and the lack of information on specific treatments for depression received by each group. Randomization at the practice level compromised the ability to using blind rating. Covering the cost of citalopram and interpersonal psychotherapy limits the study of cost as a barrier to treatment. Finally, attrition was relatively high, perhaps because the study enrolled a probability sample consisting of patients less interested in study participation than in help-seeking. Nonetheless, probability sampling permits safer generalization of findings. Moreover, the baseline clinical characteristics of those assessed at 24 months were similar to those of the sample assessed at baseline. Finally, taking dropout into consideration did not affect differences between treatment groups significantly. Another limitation is that suicidal ideation was assessed at single points in time, whereas suicidal thoughts wax and wane.

Strengths of this study include its random sampling and a sensitive screening approach designed to identify most patients with depression. These procedures allow generalization of findings to whole practices. Furthermore, the practices were heterogeneous, consisting of small, large, inner-city, rural, academic, and privately owned practices. Finally, patients with suicidal ideation, cognitive impairment, and medical burden were included in the sample. Therefore, these findings may be relevant to real-world practices.

The primary care setting is a strategic point from which to fight suicidality and depression since most elderly patients suffering from these syndromes are treated by primary care physicians. Sustained collaborative care maintains high utilization of depression treatment, reduces suicidal ideation, and increases response and remission rates in major depression over a period of 2 years. Rising response and remission rates between months 18 and 24 underscore the value of long-term care. These observations suggest that sustained collaborative care increases depression-free days and perhaps longevity.