The loss of an unborn child after induced termination of pregnancy because of fetal anomaly in late pregnancy is a major life event that is accompanied by intense acute psychological reactions. Instead of joy and happiness, women have to face grief and mourning. Although they did not actually know the child, women experience the loss as intensely as that of a close and emotionally important person, sometimes with enduring reactions of grief and severe psychological problems

(1 –

3) . Grief-related cues, such as baby buggies, toys, and other babies, provoke loss-related emotions in women after termination of pregnancy and are therefore often avoided in everyday life.

In general, grief as an instant and individual response to the loss of an emotionally important person refers to affective, physiological, and psychological reactions

(4) . The loss of a loved one is often spoken of in terms of painful feelings, and increasing evidence has shown that such metaphors do indeed reflect what is happening in the brain. Psychological pain, especially the separation from or the loss of close others, seems to share the same neural pathways that are associated with physical pain

(5,

6) . One explanation for this phenomenon is the importance of close social ties for survival in mammals. Panksepp and colleagues

(7) were the first to discuss the overlap in the systems underlying physical and social pain based on the effect of exogenous opiates on pain tolerance in socially isolated puppies.

Imaging studies of the physical pain system have most consistently produced activation in somatosensory cortices, the insula, the anterior cingulate cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, and the thalamus

(8) . The social pain network, as proposed by Eisenberger

(6), encompasses activations in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the insula, the right ventral prefrontal cortex, and the periaqueductal gray matter in the brainstem during social rejection.

There have been limited functional imaging studies of grief-related activation patterns

(9 –

11) . To our knowledge, no study has investigated acute grief after the loss of a child. In a study of women who had lost a first-degree relative in the past year, Gündel and colleagues

(9) observed an increased activation in the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, the insula, the inferior temporal and fusiform gyrus, the cuneus, and the superior lingual gyrus during the presentation of photographs of the deceased. O’Connor and colleagues

(10) compared bereaved women with complicated or uncomplicated grief after the death of a mother or sister in the past 5 years. They observed activation in pain-related brain areas in both groups, although the women with complicated grief also showed activity in the nucleus accumbens, a subcortical structure that has been associated with reward.

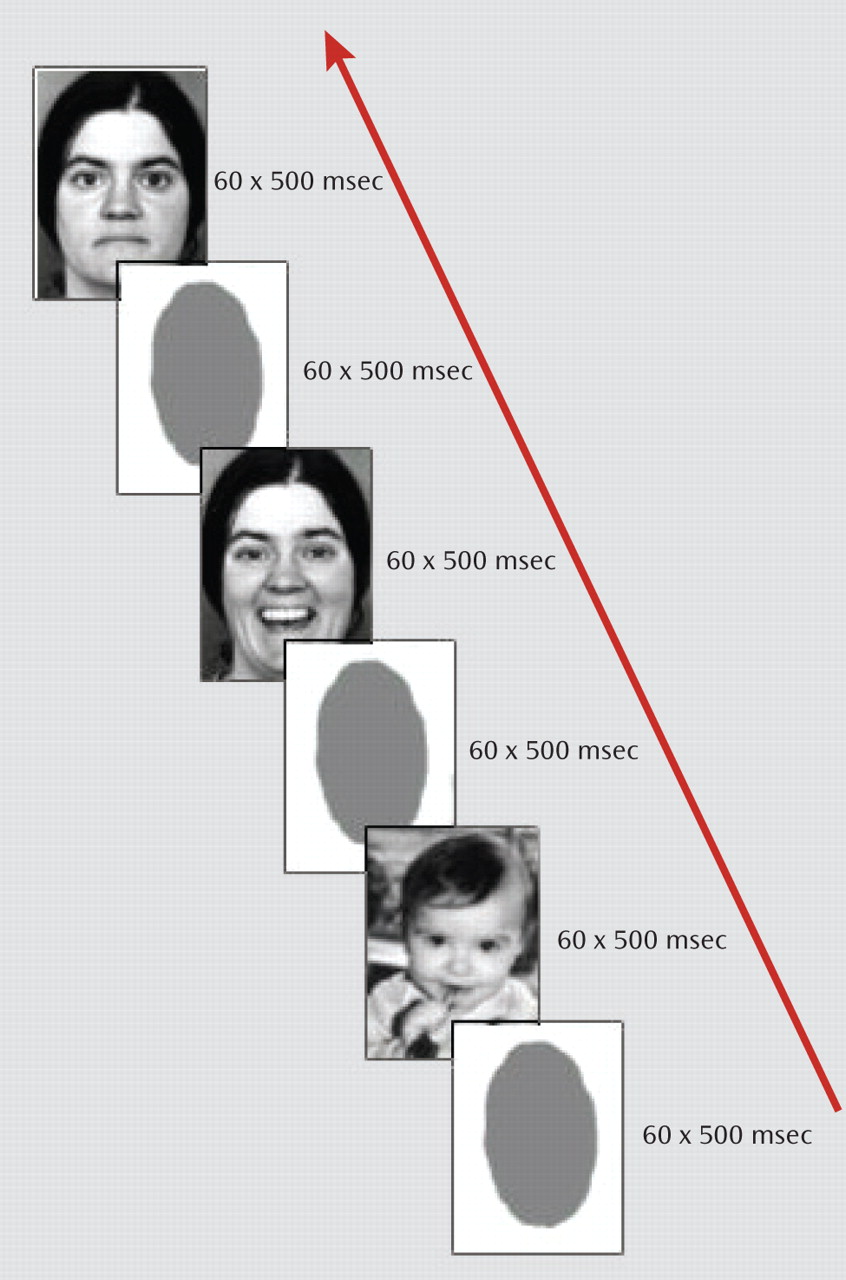

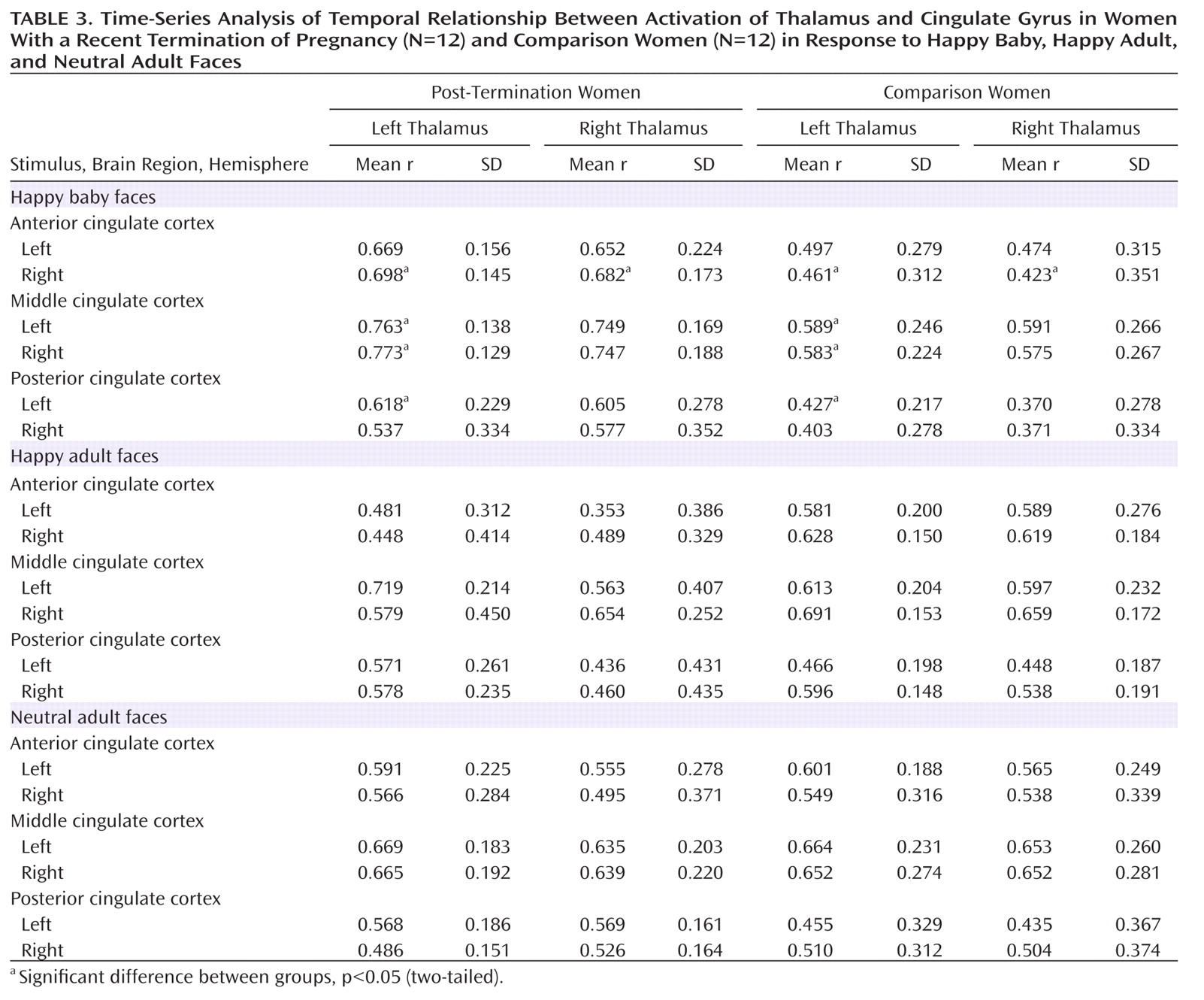

In this study, we used functional MRI (fMRI) to investigate grief in women within 2 months after termination of pregnancy. To elicit acute grief, we used pictures of happy baby faces and compared results to those elicited by happy and neutral adult faces and a no-face baseline condition. We hypothesized that there would be greater activation in pain-related areas of the brain in post-termination women than in a comparison group of young women who had recently given birth to a healthy child. Building on nonhuman mammalian investigations, the thalamocingulate division has been regarded as important in mammalian mother-infant attachment as well as maternal behavior in humans

(12,

13) . We analyzed functional connectivity between the thalamus and the cingulate gyrus and hypothesized that a stronger thalamocingulate connectivity would be observed in post-termination women during the visualization of baby faces.

Discussion

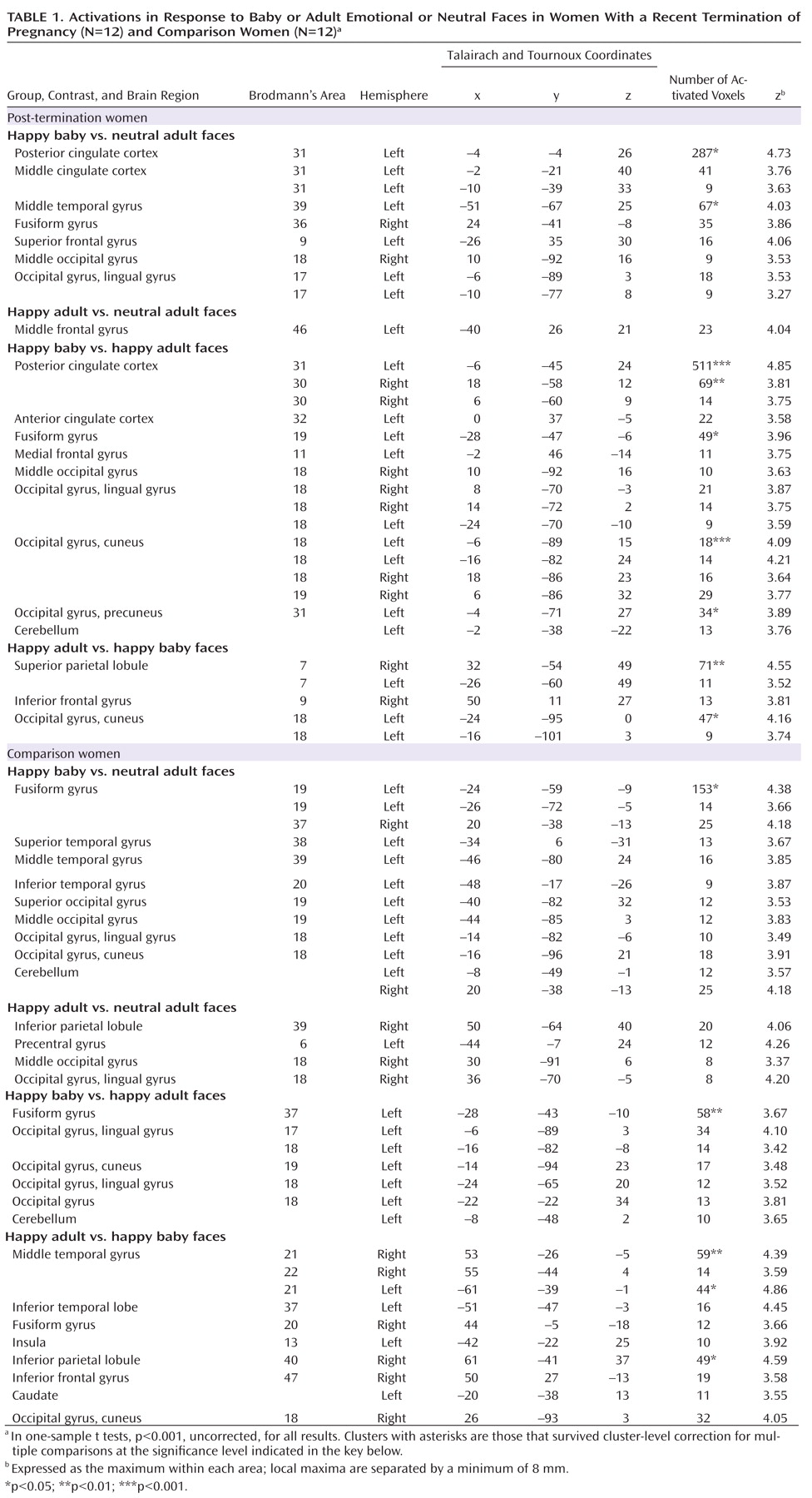

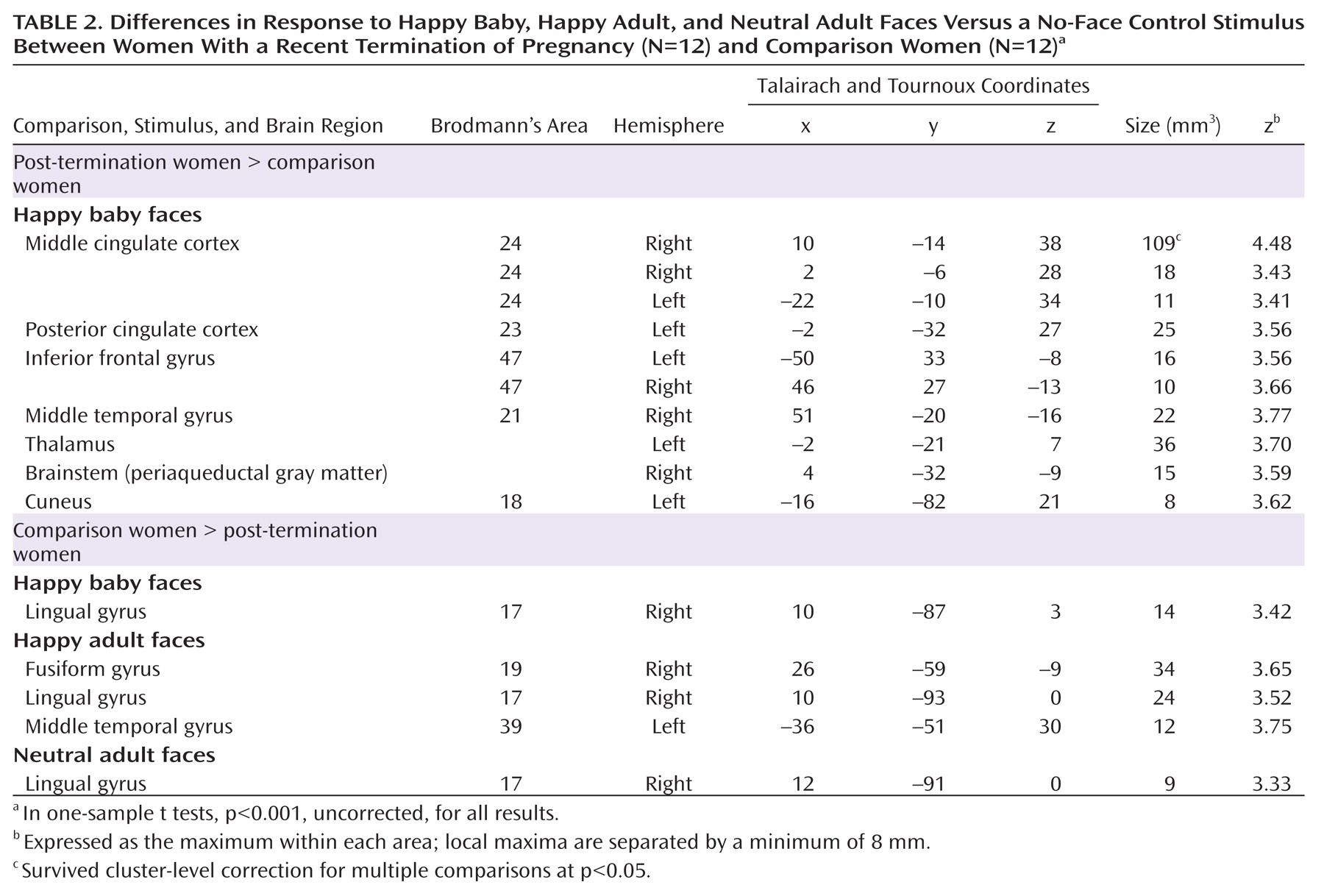

The death of a child is an incomprehensible and devastating loss causing intense parental grief and mourning. In our study, after the loss of an unborn child due to malformation, women showed increased activation in a large number of brain areas related to the physical pain network while viewing happy baby faces. As psychological pain has recently been shown to share some of the same neural pathways that are associated with physical pain, our results are consistent with data from previous studies of grief and social rejection

(6,

9 –

10) . One mechanism that has been suggested as an explanation of why social separation is considered painful follows from the evolutionary advantages of close social ties for survival in mammalian species.

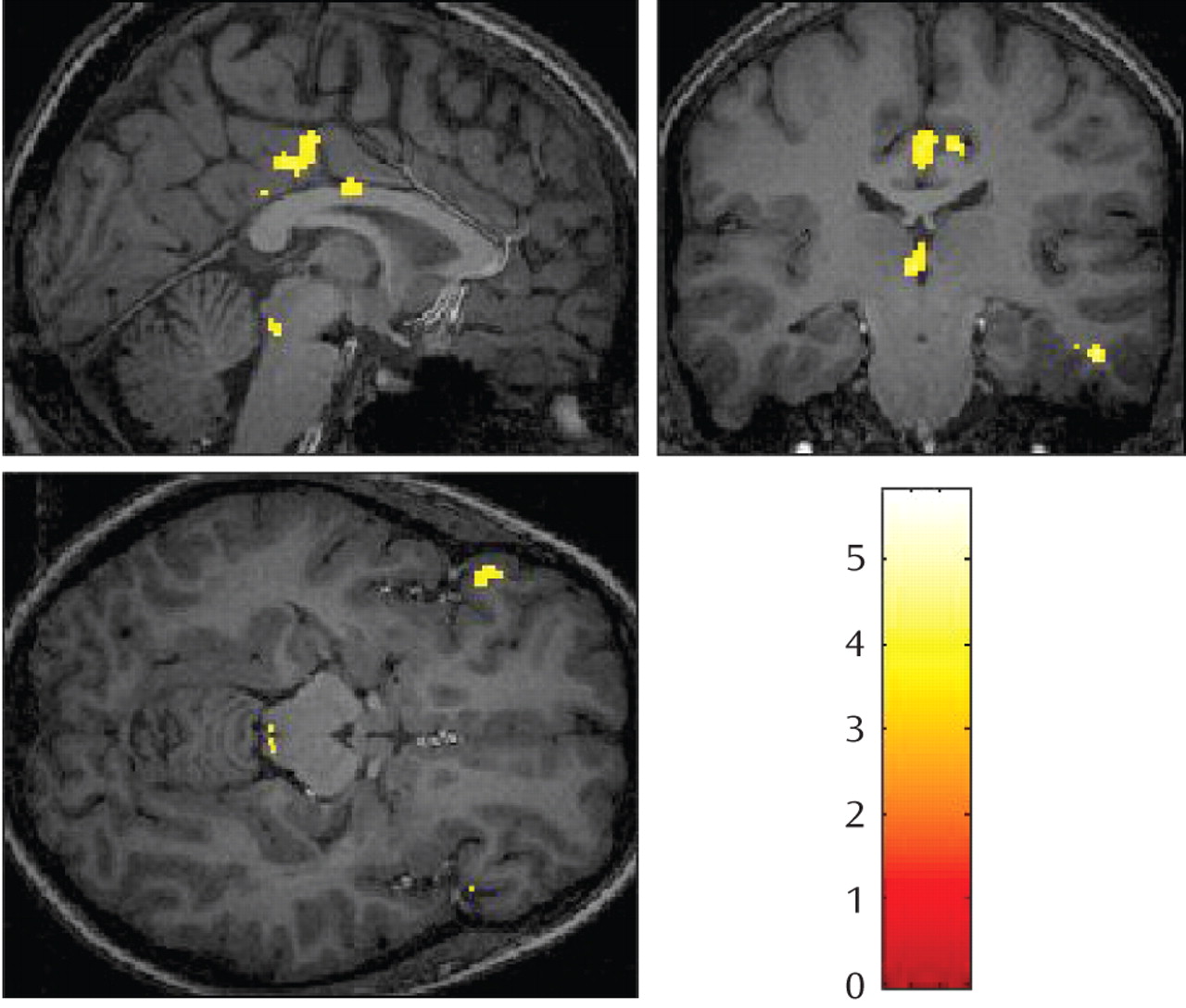

The dorsal anterior or middle cingulate cortex has been shown to activate in response to physical as well as social pain. It has been related to the affective component of physical pain and the distress of social rejection. In our study, increased activity in the middle cingulate cortex was distinctly observed for happy baby faces in post-termination women, thus underlining the assumption that the observed differences in activation are related to grief triggered by specific cues and are not caused by the depressed and mourning affective state of post-termination women.

Additionally, we observed an increased activation in the posterior cingulate gyrus during the processing of happy baby faces in post-termination women. Posterior cingulate gyrus activity as been shown to be elicited by an interaction between emotion and memory

(31), specifically by the arousal dimension of emotional stimuli. It appears to be important in monitoring the environment for emotionally salient events and for the comparison of these events to memories. Increased posterior cingulate gyrus activity has been demonstrated in individuals who had experienced a bank robbery when the robbery video was compared to a control video

(32) . Gündel and colleagues

(9) reported an increased activation in the posterior cingulate gyrus that was evoked by photographs of the deceased and by viewing grief-related words.

The inferior frontal gyrus, especially BA 47, has repeatedly been associated with regulating feelings of physical as well as psychological pain or negative affect

(6,

33 –

35) . Activity in this area is modified by voluntary regulation of emotional responses, such as using cognitive control to reduce negative emotions

(33), and in our study could be related to the attempt of post-termination women to control painful feelings.

The thalamus and periaqueductal gray matter are involved in pain processing as well as in attachment behavior in nonhuman mammals

(36 –

38) . In studies of physical pain, attentional processes and vigilance have been shown to increase thalamic activity, and thus thalamic activation might reflect a general arousal reaction to pain, whereas the periaqueductal gray matter is regarded as the key structure for pain inhibition

(8) . Furthermore, localized electrical stimulation of the dorsomedial thalamus and periaqueductal gray matter in the brainstem has been shown to provoke separation cries in mammals.

MacLean

(39) hypothesized that the brain’s thalamocingulate division is important in mammalian mother-infant attachment behavior, such as infant crying and a mother’s caretaking response. Furthermore, in cingulate-lesioned mice, the degree of maternal behavior impairment appeared to correlate with the degree of accompanying anterior thalamic nuclei degeneration

(40) . Thus, increased functional connectivity between the cingulate gyrus and the thalamus during the processing of baby faces in post-termination women strongly underlines the hypothesis of an involvement of the maternal attachment network in emotional distress after the death of a child.

Using unfamiliar baby faces as emotional cues in both groups, we attempted to minimize any contributions to grief-related activations other than the subjective experience of grief itself. In studies using photos of the deceased, familiarity could not be excluded as a relevant variable to influence activation patterns

(9,

10) .

Significantly stronger activations during the processing of happy baby and adult faces in comparison women relative to post-termination women were restricted to temporo-occipital areas. Recent neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that the visual presentation of emotionally charged compared to neutral stimuli activates not only emotion-specific brain areas but also extensive areas in the extrastriate cortex

(41,

42) Interestingly, whereas neuroimaging research reported a common effect of physiological arousal on perceptual cortical processing with greater overall magnitude of visual cortical response to both negative and positive stimuli, behavioral research suggests that positive affect broadens and negative affect narrows the distribution of one’s field of view. Thus, significantly stronger activations in comparison women relative to post-termination women might be related to an overall more positive affect in comparison women.

There are some limitations to our study. First, we used a passive viewing paradigm that does not provide behavioral data. Thus, one might assume that post-termination women withdrew their attention from the baby faces to avoid any emotional trigger reminding them of their loss. Increased activations in a large number of visual cortical areas, such as the lingual gyrus, the middle occipital gyrus, and the cuneus, however, provide evidence for the active viewing of emotional cues in post-termination women, since activation in visual cortical areas has been correlated with the emotional valence of stimuli

(43) . Moreover, we were unable to monitor physiological parameters to control for changes in blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing.

Nevertheless, our data suggest an extensive overlap in neural networks of grief and physical pain and also suggest a close relationship between emotional distress in maternal attachment and the neural pain network. Improvement in our understanding of the neurobiological background of grief and mourning will aid us in the development of more efficient and effective strategies to prevent prolonged and complicated grief in individuals after social loss.