Comparisons of the profile and magnitude of the neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia patients with those of patients with other psychotic disorders might have important implications for understanding the pathogenesis of these disorders and for nosological models of psychotic disorders.

Many reports have suggested that patients with other psychotic disorders also demonstrate a disruption in normal neuropsychological performance (

5–

7). The majority of research has focused on the comparison of schizophrenia with bipolar disorder. Although some studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia manifest more severe neuropsychological impairments (

8–

10), others have not detected differences in the severity of impairments between patients with bipolar psychosis and patients with schizophrenia (

11,

12). Furthermore, studies comparing neuropsychological performance between patients with schizophrenia and patients with psychotic depressive disorder are rare (

13–

15).

A major limitation of most previous studies is that they used clinical rather than epidemiological samples. Epidemiological samples are population-based, whereas clinical samples involve patient series, not complete populations. As a result, it is difficult to generalize from studies using clinical samples. Previous studies of first-episode psychosis patients have been well conducted and sometimes consisted of large samples. However, these studies varied considerably in terms of the sources of participant ascertainment (e.g., university clinics, referral centers, inpatient samples) and the age, duration of illness, and medication status of patients. Moreover, while some studies used specific diagnostic groups, others examined heterogeneous groups. These issues further hinder the interpretation of this research and the degree to which it can be generalized.

In the present study, we compared neuropsychological performance among patients in the following four major diagnostic groups who were experiencing their first episode of psychosis: patients with schizophrenia, patients with bipolar disorder or mania, patients with depressive psychotic disorder, and patients with other psychotic disorders. To examine specificity, we compared the performance of each diagnostic group with that of healthy comparison subjects, followed by direct comparison of patients with nonschizophrenia psychotic disorders with schizophrenia patients. Finally, patients with affective psychosis were also compared. Three features of the present study are especially important. First, to our knowledge, this study represents the largest epidemiological cohort of first-episode psychosis patients with neuropsychological data. Second, a large comparison sample was epidemiologically ascertained, enabling detailed and careful comparisons with patients. Finally, both patient and comparison samples are ethnically diverse, thus increasing the potential to generalize our results.

Method

AESOP Study

The data were derived from baseline scores in the Aetiology and Ethnicity in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses (AESOP) study, a population-based, case-control study of first-episode psychosis. AESOP was approved by local research ethics committees, and each participant gave written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. The study identified all cases of first-episode psychosis (ICD-10: F10–F29 and F30–F33) in patients aged 16 to 65 years who presented to specialist mental health services in tightly defined catchment areas in the United Kingdom (South-east London, Nottingham, and Bristol) between September 1997 and August 2000. All potential case subjects who made contact with psychiatric services for the first time (including adult community mental health teams, inpatient units, forensic services, learning disability services, adolescent mental health services, and drug and alcohol units) were screened. Exclusion criteria were previous contact with health services for psychosis, organic causes of psychotic symptoms, transient psychotic symptoms as the result of acute intoxication (as defined by ICD-10), and an IQ <50. The study further included a random sample of comparison subjects with no past or present psychotic disorder who were recruited using a sampling method that matched case and comparison subjects by area of residence. A detailed overview of the AESOP study design and methods has been published elsewhere (

16).

Analytic Cohort

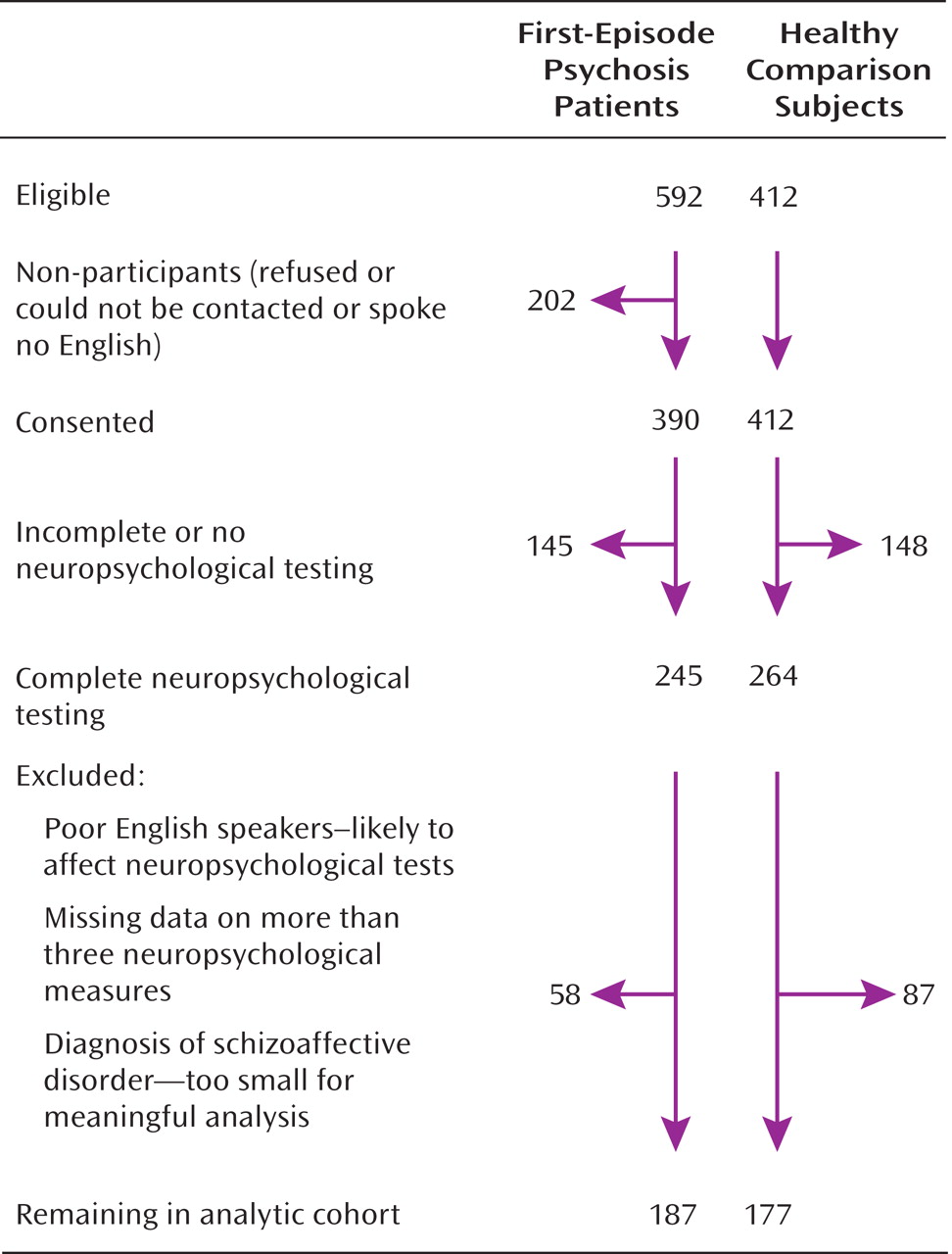

The derivation of the sample included in the present analysis is illustrated in

Figure 1. The analytic cohort consisted of subjects who had a consensus ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia (F20 [N=65]); bipolar disorder or mania (F30.2, F31.2, or F31.5 [N=37]); depressive psychosis (F32.3 or F33.3 [N=39]); or other psychotic disorders, which included persistent delusional disorders (F22), acute and transient psychotic disorders (F23), other nonorganic psychotic disorders (F28), and unspecified nonorganic psychosis (F29) (total N=46), as well as 177 healthy comparison subjects. For all case and comparison subjects, there was complete interview data as well as 1) IQ measurements on the National Adult Reading Test (

17) and a short form of the WAIS–R (

18) and 2) a neuropsychological test battery. Both case and comparison subjects were required to be native speakers of English or to have migrated to the United Kingdom by age 11. The latter requirement ensured that all participants had a good command of English, even as a non-native language, since all would have completed at least their secondary education in the United Kingdom, thus minimizing the effect of linguistic or cultural biases on the performance of a multiethnic sample. In accordance with previous studies (

15), case and healthy comparison subjects with missing data for more than three neuropsychological measures were excluded.

Diagnostic Assessment and Symptom Data

Clinical data were collected using the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (

19,

20). The Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry incorporates the Present State Examination, Version 10, which is used to elicit symptom-related data at the time of presentation. Ratings on the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry are based on clinical interview, case note review, and information from informants (e.g., health professionals, close relatives). Researchers were trained to utilize this assessment tool via a World Health Organization-approved course and established prestudy reliability using independent ratings of videotaped interviews. Principal investigators at each study center produced independent diagnostic ratings for 20 case vignettes chosen randomly from the entire sample. The kappa scores ranged from 1.0, for psychosis as a category, to between 0.6 and 0.8, for individual diagnoses. ICD-10 diagnoses were determined using the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry data on the basis of consensus meetings with one of the principal investigators and other members of the research team.

Symptom ratings.

Symptom ratings were calculated according to the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry Item Group Checklist algorithm (

19). This algorithm combines scores from several items specific to a particular group of symptoms. For example, the checklist item "special features of depressed mood" is defined by the following group of symptoms: feeling of loss, unremitting depression, morning depression, preoccupation with catastrophe, pathological guilt, guilty ideas of reference, loss of self-esteem, and dulled perception. Scores for individual item groups range from 0 (absent) to a maximum of 2, depending on the frequency and severity of symptoms. Subsequent to a recent factor analysis (

21), individual item groups were aggregated into the following three symptom dimensions: 1) negative symptoms (flat and incongruous affect, poverty of speech, motor retardation and catatonic behavior, and nonverbal communication); 2) reality distortion (bizarre delusions and interpretations, delusions of reference, delusions of persecution, experience of disordered form of thoughts, nonspecific auditory hallucinations, and nonaffective auditory hallucinations); and 3) depression (depressed mood, depressive delusions and hallucinations, and special features of depressed mood).

Neuropsychological Assessment

Sixteen neuropsychological measures were selected to assess the following six domains: 1) learning and memory (verbal and visual); 2) executive functions and working memory; 3) attention, concentration, and mental speed; 4) language; 5) visuo-construction/perceptual abilities; and 6) WAIS–R verbal intelligence. Learning and memory were assessed using trials 1 through 5 (learning), trial 6 (immediate recall), and trial 7 (delayed recall), respectively, of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test as well as the visual reproduction subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised. Executive functions and working memory were evaluated using the Trail Making Test, Part B; Letter-Number Span Test; and Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices sets AB and B. Attention, concentration, and processing speed were measured using the Trail Making Test, Part A, and WAIS–R digit symbol subtest. Language was evaluated using WAIS–R category fluency (semantic ["body parts," "fruits," and "animals"]) and letter fluency (phonemic [F, A, and S]) tasks. Visual-spatial perception and organization were assessed using set A of Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices and WAIS–R Block Design. WAIS–R verbal intelligence was assessed by the vocabulary and comprehension subtests. (For a detailed description of measures, see references 22, 23.)

Premorbid intelligence was estimated using the National Adult Reading Test (

17). Full-scale IQ was derived from the WAIS–R (

18) subtests in the neuropsychological test battery. All tests were administered and scored by specially trained research workers.

Creating Norms for Neuropsychological Tests

A regression-based approach was used to create normative standards for the neuropsychological tests. Age, gender, ethnicity, and education were regressed on each of the neuropsychological measures in the healthy comparison sample. Next, scores were adjusted on the basis of the regression results, and standard scores (i.e., z) were created. The regression-corrected scores were also inspected for both skewness and kurtosis. Only the Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices and Trail Making Test, Part A and Part B, had significant skewness, and these variables were log-transformed before standardization. The same adjustment and standardization procedure was applied to the patient groups, using the normative standards from the healthy comparison group.

Data Analysis

Differences in sociodemographic and intellectual characteristics among the five groups were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models, Pearson's chi-square, or Fisher's exact test when appropriate. Differences in performance on each normative-adjusted neuropsychological measure were examined using ANOVA models. The significance level was adjusted for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction and was conservatively set at p≤0.003 (0.05/16). For descriptive purposes, we also carried a priori-defined comparisons. First, each diagnostic group's performance was compared with that of the healthy comparison group. Next, the following direct comparisons of performance among the patient groups were conducted: schizophrenia group versus bipolar disorder or mania group, schizophrenia group versus depressive psychosis group, and bipolar disorder or mania group versus depressive psychosis group. A significance level for these a priori comparisons was set at p≤0.007 (0.05/7). As a result of missing data on individual tests, degrees of freedom varied slightly. Pearson's correlations were performed between each of the neuropsychological variables and the three specific symptom dimensions (negative symptoms, reality distortion, and depression). ANOVA models were followed by ANCOVA models, which adjusted for IQ.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

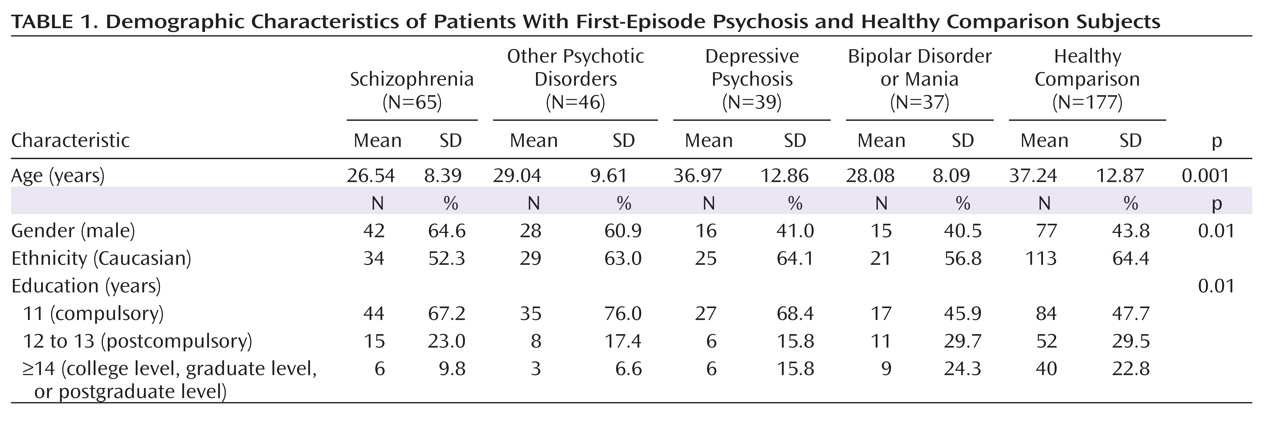

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of the cohort. There were significant group differences in age (F=15.6, df=4, 359, p<0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or mania, and other psychotic disorders were significantly younger than healthy comparison subjects. The five groups also differed significantly in gender distribution, with an excess of men in the schizophrenia group relative to the other diagnostic groups (χ

2=12.73, df=4, p<0.01). All groups significantly differed in measures of education (χ

2=19.57, df=8, p<0.01) but not in ethnicity.

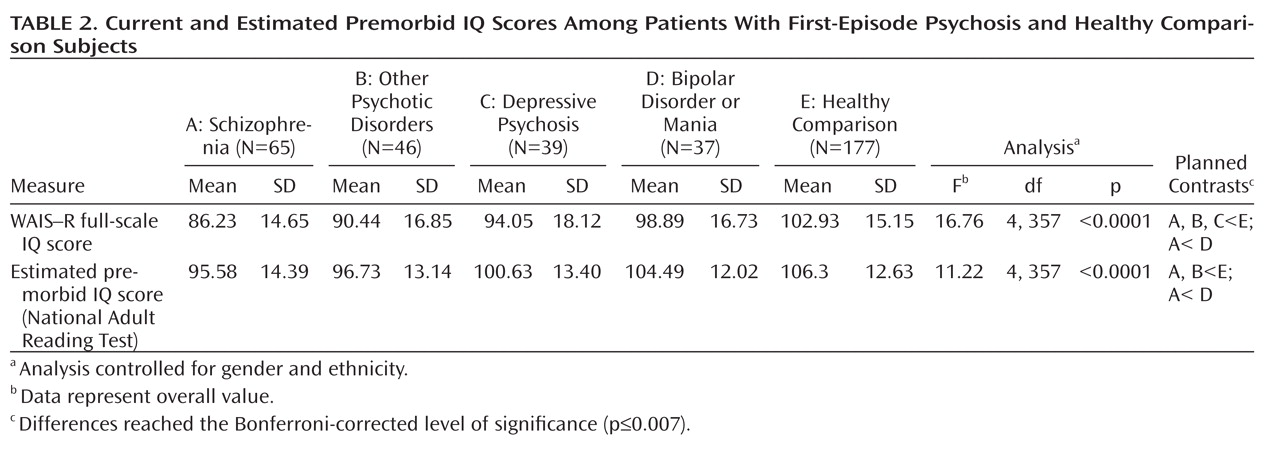

Current and Estimated Premorbid IQ

There were overall significant group differences in current and estimated premorbid IQ (

Table 2). Descriptive analyses demonstrated that relative to healthy comparison subjects, the schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders patients had significantly lower scores for both current and estimated premorbid IQ. The depressive psychosis group had a significantly lower current IQ score relative to healthy comparison subjects. Patients in the schizophrenia group also had significantly lower current and estimated premorbid IQ scores compared with the bipolar disorder or mania group. All of the aforementioned group differences reached the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance (p≤0.007).

Neuropsychological Performance

Comparison between diagnostic groups and healthy comparison subjects. ANOVA models demonstrated that for 10 of the 16 neuropsychological measures, overall group differences reached the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance (p≤0.003). The measures that did not reach the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance were Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices set AB (p=0.003), vocabulary (p=0.009), comprehension (p=0.009), and visual memory (p=0.04). No overall group differences were observed for set A on the Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices and letter fluency.

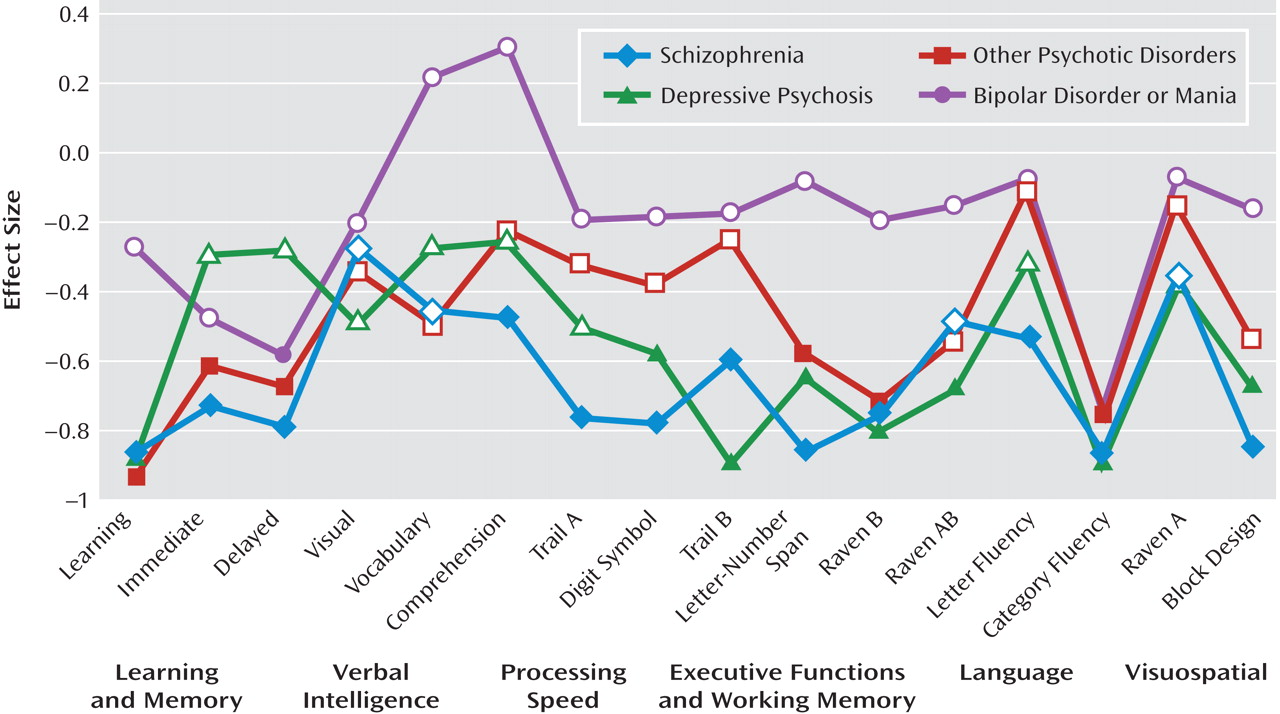

The neuropsychological performance profiles of the four diagnostic groups and results of the descriptive analyses that followed the ANOVA models, comparing each diagnostic group with the healthy comparison group, are presented in

Figure 2. The schizophrenia group exhibited widespread impairment and performed worse than healthy comparison subjects on all measures (all p values <0.05). For 12 of the 16 measures, these differences also reached the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance. Patients with depressive psychosis and other psychotic disorders also demonstrated widespread impairments relative to healthy comparison subjects. Differences reached the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance for eight measures in the depressive psychosis group and six measures in the other psychotic disorders group. In contrast, patients in the bipolar disorder or mania group performed significantly worse than healthy comparison subjects only on measures of delayed verbal memory and category fluency (all Bonferroni-corrected level of significance p values ≤0.007).

We also examined Pearson's correlation coefficients across patient groups between neuropsychological test scores and symptom dimensions. More severe negative symptoms were associated with poorer performance on the following measures: vocabulary (r=–0.193, p=0.04); comprehension (r=–0.193, p=0.04); digit symbol (r=–0.38, p=0.001); Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices set B (r=–0.231, p=0.02); Trail Making Test, Part A (r=–0.270, p=0.005) and Part B (r=–0.207, p=0.04); Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (r=–0.238, p=0.01); letter fluency (r=–0.284, p=0.006); and category fluency (r=–0.242, p=0.02). More severe reality distortion was associated with poorer performance only on the Trail Making Test, Part B (r=0.252, p=0.03). Severity of depressive symptoms was not significantly associated with performance on any neuropsychological test.

Comparisons among diagnostic groups. The bipolar disorder or mania group performed better than the other patient groups on almost all neuropsychological measures. This group exhibited better performance relative to the schizophrenia group on measures of vocabulary and comprehension, digit symbol, letter-number span, and block design, and scores were statistically significant at the Bonferroni-corrected level (p≤0.007).

Role of general intellectual ability. Differences in performance on neuropsychological tests could be a function of current general intellectual ability. Therefore, in an exploratory analysis, we compared the patient groups and healthy comparison subjects while adjusting for current IQ. After adjustment, many of the specific neuropsychological differences were attenuated. None of the ANCOVA models reached a Bonferroni-corrected level of significance, but a number of measures reached a conventional threshold of significance (p<0.05). These were measures for verbal learning (p=0.006), category fluency (p=0.004), and the Letter-Number Span Test (p=0.02).

Descriptive analyses demonstrated that after adjustment for IQ, several comparisons were statistically significant at the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance. The schizophrenia group was significantly impaired relative to the healthy comparison group on the Letter-Number Span Test (p=0.003). The depressive psychosis group was significantly impaired relative to healthy comparison subjects on measures of verbal learning (p=0.003) and category fluency (p=0.004) and on the Trail Making Test, Part B (p=0.006). Patients with other psychotic disorders were significantly impaired relative to healthy comparison subjects on verbal learning (p=0.003). The bipolar disorder or mania group was also significantly impaired relative to the healthy comparison group on category fluency (p=0.003). Direct comparisons between the diagnostic groups were not statistically significant at the Bonferroni-corrected level.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to compare neuropsychological performance in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or mania, depressive psychotic disorder, and other psychotic disorders as well as in healthy comparison subjects. Despite extensive neuropsychological investigation in psychiatric disorders, to our knowledge this is the first epidemiological case-control study that includes a broad spectrum of patients experiencing their first episode of psychosis. The main findings are that moderate to severe neuropsychological impairments characterize all psychotic disorders following the first psychotic episode, and, by and large, the magnitude of impairment in specific neuropsychological functions reflects a generalized cognitive deficit. Differences in neuropsychological performance between patient groups and healthy comparison subjects and among the different patient groups were largely accounted for by differences in general intellectual ability.

The present study is novel in several ways. First, no prior study has examined neuropsychological function in the category of other psychotic disorders, which is a large clinical group that has been difficult to study. Second, an ethnically diverse sample was assessed. Third, the availability of a well-characterized, large, epidemiologically ascertained comparison group (which is difficult to obtain) was included, increasing the validity and generalizability of our findings. Fourth, the diagnostic procedures were blind to neuropsychological assessment.

Researchers have long debated the nature of the cognitive impairments in schizophrenia, particularly the relationship between cognition and psychosis, and whether schizophrenia is characterized by a generalized impairment versus independent deficits in specific cognitive impairments (

24). Many neuropsychological investigations have sought to identify specific cognitive deficits that might represent more fundamental "core" impairments, reflecting underlying brain regions or networks related to the etiology of the disorder (

10,

13,

25). Similar investigations have been carried out with respect to other psychotic disorders. Determining if cognitive impairments are either more generalized across domains or more specific to particular domains also has important implications for clinical assessment, intervention design, and genetic research (

24). The present results highlight the degree of general cognitive impairment across psychotic disorders. Studies of schizophrenia patients without a long history of illness or medication have documented a generalized deficit (

26,

27), and these findings have been extended to chronic patients in a series of recent studies conducted by Gold (

24,

28), demonstrating that the cognitive deficit in schizophrenia is largely generalized across domains. Studies of generalized and specific neuropsychological functions in bipolar disorder and psychotic depression have been conducted in chronic patients (

10,

29) and also suggest a generalized cognitive impairment.

Despite the evidence in the present study that the cognitive deficit in psychotic disorders is generalized across cognitive domains, additional specific deficits were also apparent. In schizophrenia, a selective deficit in working memory was evident. Working memory involves the ability to maintain and manipulate information over short periods of time and has been associated with frontal lobe function (

25,

30). Deficits in working memory have been implicated as potential core deficits in schizophrenia (

31), and working memory processes have been shown to share a genetic basis with schizophrenia (

32).

A deficit beyond general intellectual impairment in verbal learning was evident in the depressive psychosis and other psychotic disorders groups. A selective impairment in memory and learning in schizophrenia has been previously hypothesized (

4) and has been associated with the temporal hippocampal region (

25). The lack of diagnostic specificity observed in the present study merits further examination.

Performance on the category (semantic) fluency test was selectively impaired, beyond general intellectual impairment, among patients with depressed psychosis and bipolar disorder or mania. This test involves the capacity to generate words belonging to a particular category and has been associated with frontal and temporoparietal function (

33). Performance on the letter (phonemic) fluency test did not reveal selective impairment. The disproportionate semantic fluency impairment may have been the result of abnormal semantic organization (

34).

Family, twin, and molecular genetic studies suggest that schizophrenia and affective psychotic disorders may share certain susceptibility genes, and there is a clear overlap in phenomenological symptoms (

35,

36). However, from a developmental perspective, there are some differences. There is large and consistent literature documenting childhood cognitive impairments preceding the onset of schizophrenia (

37–

39). Broadly defined affective psychosis has also been shown to be preceded by developmental impairment, but the effects are not as strong (

40,

41) and seem to be confined to early-onset diagnosis (

40). Premorbid intellectual functioning was relatively intact in bipolar disorder or mania patients in the present study, which is consistent with that of the study conducted by Cannon et al. (

38). This may suggest that the onset of psychosis is associated with the appearance of a generalized deficit, superimposed upon a varying level of premorbid intellectual reserve that is least in schizophrenia and greatest in bipolar disorder.

The present study has a number of strengths. It is a large, first-episode psychosis study incorporating a population-based epidemiological sample. The fact that we included a large healthy comparison group also strengthens the interpretation of our results. However, the following limitations of the study should also be acknowledged. We had insufficient information on medication to reliably determine dosage, and no patients were drug naive. Medication type and side effects can influence subjects' neuropsychological performance. Nevertheless, we observed only weak correlations between neuropsychological functioning and symptom severity. Another limitation is that patients were assessed soon after their first hospital admission. Diagnostic changes may occur over time. However, Schwartz et al. (

42) conducted a follow-up assessment in a large sample of first-admission patients with psychosis and found that diagnostic consistency at 24 months after the first admission was high for patients with schizophrenia (92%), bipolar disorder (83%), and psychotic depression (74%). The most frequent shift in diagnosis at 24 months was to schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

In summary, the present results add to the evidence indicating that cognitive deficits are present in all psychotic disorders early in their course but are most severe and pervasive in schizophrenia and least pervasive in bipolar disorder or mania. They also add to the growing body of clinical, neurophysiological, and genetic evidence supporting a continuum between schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders (

35). Future research involving the present cohort will be aimed to assess the stability of neuropsychological deficits across disorders and the relationship of these deficits to clinical and functional outcome. Such knowledge is likely to be valuable in designing early interventions for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.