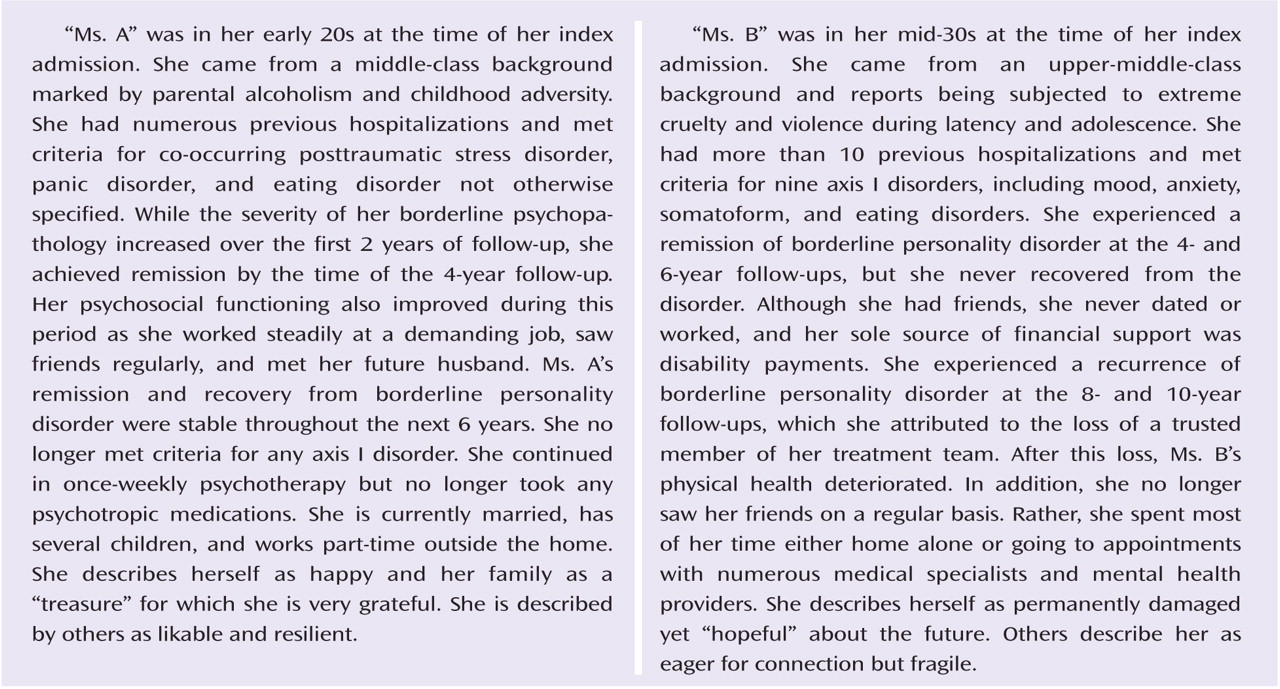

Clinical experience suggests that some patients with borderline personality disorder both exhibit only mild symptoms and function well psychosocially over time. Other patients remain quite symptomatic and may in addition be unable to work or attend school successfully. They may also become increasingly socially isolated or move from one contentious relationship to another.

Four large-scale, long-term follow-back studies of the longitudinal course of borderline personality disorder were reported in the 1980s (

1–

4). At follow-up, the patients in these studies received a mean score of 63–67 on either the Health-Sickness Rating Scale (

5) or the Global Assessment Scale (

6)—precursors to the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF). This consistent finding has usually been interpreted to mean that the average borderline patient attains a reasonably good overall outcome a mean of 14–16 years after his or her index admission.

In the 1990s, the National Institute of Mental Health funded two large-scale prospective studies of the long-term course of borderline personality disorder—the McLean Study of Adult Development (

7) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (

8). The McLean study found steady, if modest, overall improvement over 6 years of prospective follow-up (

9), with mean GAF scores moving from the incapacitated range at baseline to the fair range at 6-year follow-up. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study found that borderline patients continued to function in the fair range of global functioning over 2 years of prospective follow-up (

10).

In the present study, which is an extension of the McLean Study of Adult Development, we assessed symptomatic remission, sustained symptomatic remission, and recovery from borderline personality disorder in a sample of 290 borderline patients who were initially inpatients. We also assessed both the time to attainment of these outcomes and the time to loss of these outcomes.

Method

All participants were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. Patients were first screened for inclusion criteria, which included age between 18 and 35; known or estimated IQ of at least 71; no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or organic conditions that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and fluency in English.

All participants provided written informed consent after receiving an explanation of the study procedures. Each participant then met with a master's-level interviewer blind to the patient's clinical diagnoses for a thorough psychosocial and treatment history and diagnostic assessment. Four semistructured interviews were administered: the Background Information Schedule (

11), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (

12), the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (

13), and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (

14). The interrater and test-retest reliability of these instruments have all been found to be good to excellent (

9,

15,

16).

At each of five follow-up waves 24 months apart, psychosocial functioning and treatment utilization as well as axis I and II psychopathology were reassessed via interview methods similar to those used at baseline by staff members blind to previously collected information. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered, along with the Revised Background Information Schedule (

17)—the follow-up analogue to the Background Information Schedule administered at baseline. Good to excellent follow-up (within a generation of raters) and longitudinal (between generations of raters) interrater reliability was maintained throughout the course of the study for variables pertaining to psychosocial functioning and treatment use (

9). Good to excellent follow-up and longitudinal interrater reliability was also maintained for assessment of both axis I and II disorders (

15,

16).

Definition of Recovery From Borderline Personality Disorder

Our measure of recovery was a GAF score of 61 or higher (which none of our participants had at baseline). This is the outcome measure used by the four follow-back studies described above (

1–

4), and it offers a reasonable description of a good overall outcome—some mild symptoms or some difficulty in social, occupational, or school functioning but generally functioning fairly well and having some meaningful interpersonal relationships. We operationalized this score to enhance its reliability and meaning. To be given a GAF score of 61 or higher, a borderline patient typically had to be in remission (defined below), have at least one emotionally sustaining relationship with a close friend or life partner or spouse, and be able to work or go to school consistently, competently, and on a full-time basis.

Definition of Remission and Sustained Remission of Symptoms

We defined symptomatic remission as no longer meeting study criteria for borderline personality disorder (DSM-III-R and Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines criteria) for a period of at least 2 years (or at least one follow-up interval), and sustained symptomatic remission as no longer meeting criteria for at least 4 years (or at least two consecutive follow-up intervals).

Statistical Analysis

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator (of the survival function) was used to assess time to remission and time to recovery from borderline personality disorder. We defined time to attainment of these outcomes as the follow-up period during which these outcomes were first achieved. Thus, possible values for these measures were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years.

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator was also used to assess time to attainment of a sustained symptomatic remission. We defined time to attainment of a sustained symptomatic remission as the follow-up period during which this outcome was first achieved. Thus, possible values for this outcome were 4, 6, 8, or 10 years.

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator was also used to assess time to recurrence after a 2-year symptomatic remission, time to loss of recovery, and time to loss of a sustained symptomatic remission. Possible values for recurrence and loss of recovery from borderline personality disorder were 2, 4, 6, or 8 years after first attaining these outcomes. Possible values for loss of sustained remission were 2, 4, or 6 years after first attaining this outcome.

Results

A total of 290 patients met both DSM-III-R and Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines criteria for borderline personality disorder. Most of the participants were female (N=233, 80.3%), and most were white (N=253, 87.2%). Their average age was 26.9 years (SD=5.8), their mean rating on the 5-point Hollingshead-Redlich socioeconomic status scale (where 1=highest and 5=lowest) was 3.4 (SD=1.5), and their mean GAF score was 38.9 (SD=7.5), indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, and mood.

Attrition was relatively low; 275 patients were reinterviewed at 2 years, 269 at 4 years, 264 at 6 years, 255 at 8 years, and 249 at 10 years. At the 10-year assessment, about 86% of participants remained in the study. Of the 41 patients who were no longer in the study, 12 had committed suicide, seven died of other causes, nine discontinued their participation, and 13 were lost to follow-up. All told, 91.9% (N=249/271) of surviving patients were reinterviewed at all five follow-up waves.

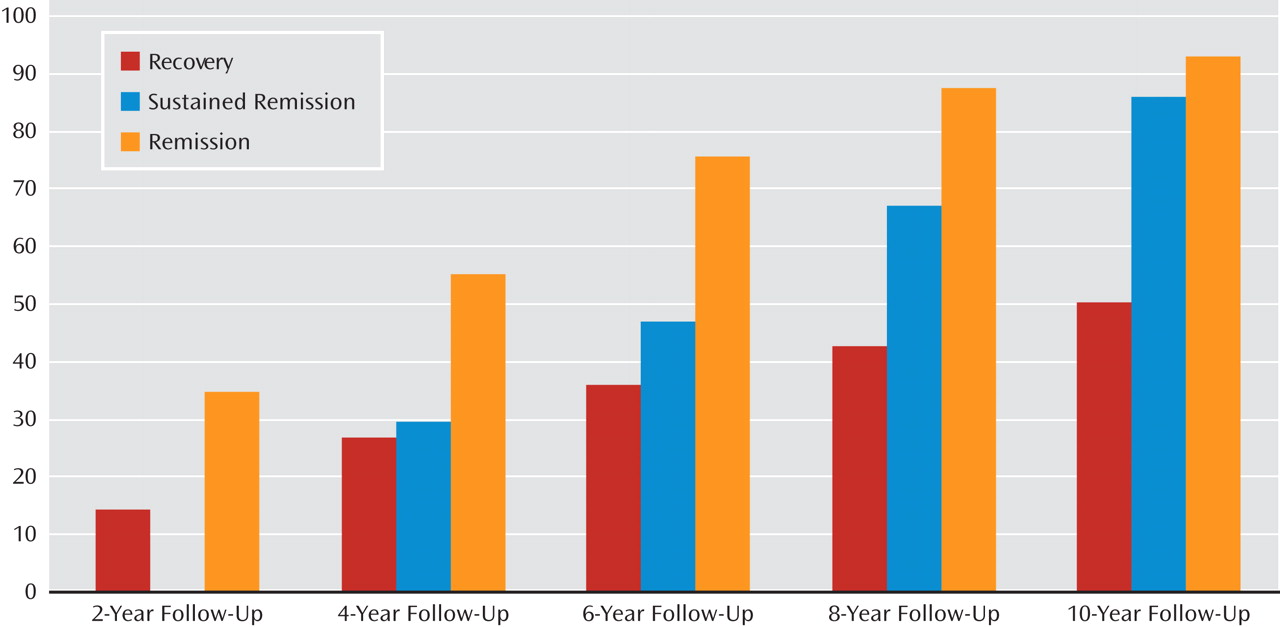

Figure 1 details time to attainment for our three outcome measures. At 10 years, 93% of patients had attained a symptomatic remission lasting at least 2 years and 86% a sustained remission lasting at least 4 years. Only 50% of patients attained recovery from borderline personality disorder, defined as having good social and vocational functioning as well as no longer meeting study criteria for borderline personality disorder during a 2-year follow-up period.

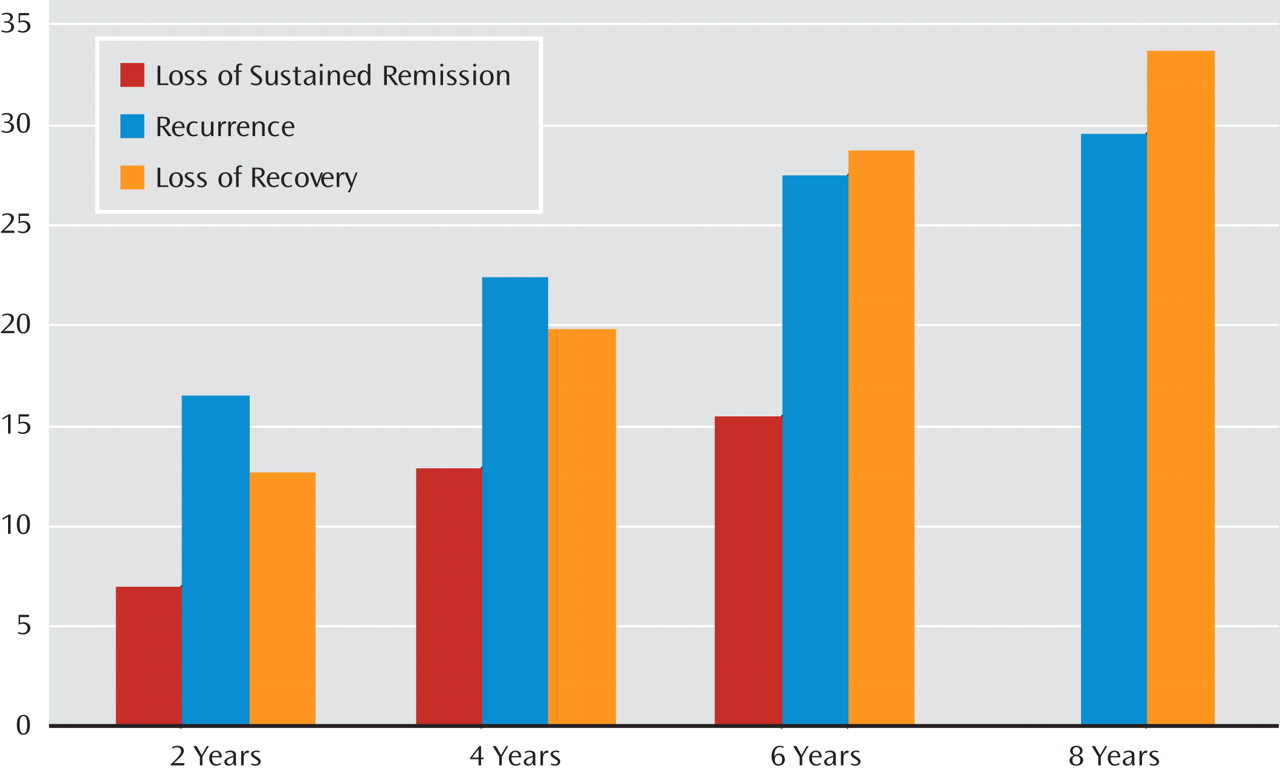

Figure 2 details time to loss for our three outcome measures. About 34% of patients who recovered from borderline personality disorder lost their recovery. About 30% of those who achieved a 2-year remission of symptoms experienced a recurrence, and about 15% of those who achieved a 4-year sustained remission experienced a recurrence.

Discussion

The two main findings that emerge from this study are that only half of our patients experienced a recovery from borderline personality disorder and that recovery from the disorder was relatively stable, with only about one-third of recovered patients later losing their recovery.

Although only half of our patients experienced recovery (which we defined as a 2-year symptomatic remission and the attainment of good social and vocational functioning), more than 90% experienced a 2-year symptomatic remission and 86% experienced a 4-year symptomatic remission. Taken together, these results support the view that good social and vocational functioning is more difficult to attain than a substantial reduction in symptom severity, an observation first clearly articulated by Skodol et al. (

10). These results also seem to suggest that most patients who achieve a 2-year remission from borderline personality disorder also achieve a remission lasting at least 4 years.

It might be argued that either of our definitions of remission could actually be seen as recovery, particularly sustained remission lasting 4 years or more. After all, studies of axis I disorders often describe remissions or even recoveries in terms of weeks and months of decreased symptom severity (

18,

19). However, our definition of recovery, which includes good social and vocational functioning as well as 2 years of symptomatic remission, is more consistent with what patients and their families believe is the goal of treatment and the desired outcome of maturation—or at least the passage of time.

This set of results is consistent with clinical experience. Many patients with borderline personality disorder exhibit far fewer symptoms as time progresses, a result found in a recent 10-year report from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (

20). For many of them, however, psychosocial functioning remains or becomes impaired over the years. Thus, it is not surprising that only half of the patients in our study attained all three aspects of recovery from borderline personality disorder: symptomatic remission and the attainment of both social and vocational competence. However, it is sobering that only half of our study sample achieved a fully functioning adult adaptation with only mild symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Our findings also suggest that the overall prognosis for many borderline patients is somewhat more guarded than that suggested by the findings of the long-term follow-back studies conducted more than 20 years ago. However, this discrepancy is not surprising given the more thorough prospective assessments used in this study.

About 34% of patients who attained recovery later lost one or more aspects of this multifaceted outcome. While this rate was similar to the rate of 30% observed for symptomatic recurrence after a 2-year remission, it was twice the rate of 15% observed for loss of a sustained 4-year symptomatic remission.

In fact, each of the three rates of recurrence we studied is lower than those found for common axis I disorders studied longitudinally, such as major depression (

21) and dysthymic disorder (

18). Additionally, the high rate of sustained symptomatic remission (86%) and the low rate of symptomatic recurrence after sustained remission (15%) are among the most optimistic findings about borderline personality disorder reported to date.

Two limitations of this study should be mentioned. The first is that all participants were initially inpatients. It may well be that borderline patients who have never been hospitalized are less impaired psychosocially and thus more likely to attain a good global outcome over time. The second is that the majority of the sample was in treatment over time, and thus the results may not generalize to untreated patients.

Taken together, the results of this study have implications for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. While clinical experience suggests that clinicians are often aware that their borderline patients have trouble achieving a good overall long-term outcome, it also suggests that the psychosocial deficits of these patients are rarely the focus of treatment. Rather, the emphasis is on symptom reduction and management. Yet our results suggest that remissions are far more common than the good psychosocial functioning needed to achieve a good global outcome. It would thus seem wise for those treating borderline patients to consider a rehabilitation model of treatment for these psychosocial deficits (

22). Such a model would focus on helping patients become employed, make friends, take care of their physical health, and develop interests that would help fill their leisure time productively. This approach could be an added component of treatment that does not directly compete for primacy with a treatment focused on symptom remission.

If a rehabilitation approach were adopted and proved effective, it could reduce the relatively high proportion of borderline patients who depend on Social Security disability benefits for support (

23). It might also help alleviate some of the feelings of worthlessness and failure that permeate the self-concept of many borderline patients who have failed to achieve the life that they—and others—had once expected for them.