Bremner (

18) has hypothesized that there may be two subtypes of acute trauma response that represent unique pathways to chronic stress-related psychopathology: one is primarily dissociative and the other predominantly intrusive and hyperaroused. Data from neuroimaging studies have shown that two subtypes of response can persist in persons with chronic PTSD and are associated with distinct patterns of neural activation upon exposure to reminders of traumatic events (

19–

21). It should be noted that these response patterns are not completely distinct and that individual patients with PTSD may show both response patterns either simultaneously or at different time points. However, PTSD patients with prolonged traumatic experiences such as chronic childhood abuse or combat trauma often show a clinical syndrome that is characterized by chronic symptoms of dissociation (

1–

3,

15) as opposed to patients who have suffered from more acute traumatic experiences (see clinical section below).

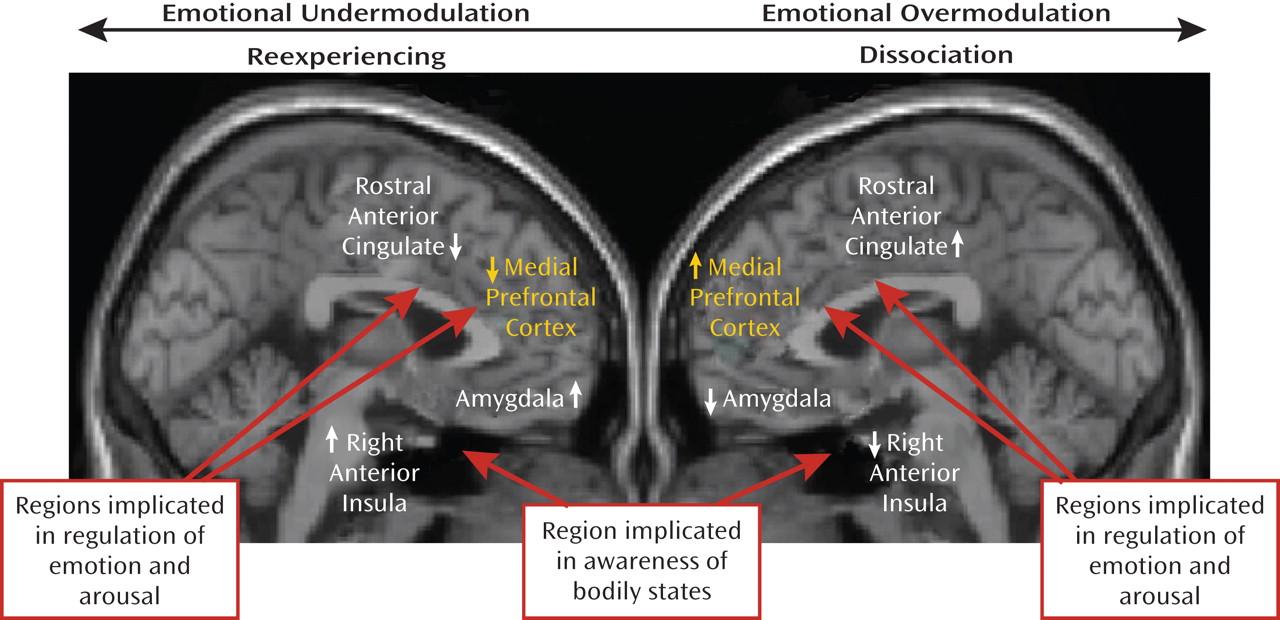

There have been investigations of the neuronal circuitry underlying reexperiencing/hyperaroused versus dissociative responses in chronic PTSD that have used functional MRI (fMRI) and script-driven imagery. In this research paradigm, patients construct a narrative of their traumatic experience that is later read to them while they are in the scanner. Patients are instructed to recall the traumatic memory as vividly as possible during "trauma scripts" and immediately afterward, while the MRI scanner measures oxygen utilization in different brain regions. Results have shown that psychobiological responses to recalling traumatic experiences can differ significantly among patients with chronic PTSD (

22,

23). Approximately 70% of patients had the subjective experience of reliving their traumatic experience and showed an increase in heart rate while recalling the traumatic memory (

19). The other 30% of PTSD subjects had a dissociative response. The latter predominantly involved subjective states of depersonalization and derealization with no significant concomitant increase in heart rate (

19). The neural correlates of reexperiencing states and dissociative states, respectively, in PTSD show

opposite patterns of brain activation in brain regions that are implicated in arousal modulation and emotion regulation. In particular these differential patterns are found in the medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the limbic system.

Emotional undermodulation: failure of corticolimbic inhibition

Patients with reexperiencing/hyperaroused PTSD exhibit abnormally low activation in medial anterior brain regions that are implicated in arousal modulation and emotion regulation more generally, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (

19) and the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (

24). Consistent with impaired cortical modulation, increased activation of the limbic system, especially the amygdala (a brain structure that has been shown to play a key role in fear conditioning), has often been observed in PTSD patients after exposure to traumatic reminders as well as to masked fearful faces (

24,

25). We conceptualize this group of patients as experiencing emotional undermodulation in response to traumatic memories. This type of response includes a subjective reliving experience of the traumatic events, such as a flashback. Reexperiencing/hyperarousal reactivity can be viewed as a form of emotion dysregulation that involves emotional undermodulation, mediated by failure of prefrontal inhibition of limbic regions.

Further support for this model is found in studies that take a dimensional approach (involving different symptom severities and associated neural activation patterns within each response subtype) to individual differences in reexperiencing symptoms in response to trauma reminders. This method examines correlations between severity of state reexperiencing to trauma scripts and brain activity in regions associated with awareness and regulation of arousal and emotions (

21). These studies have shown that severity of state reexperiencing was positively correlated with activation in the right anterior insula, a brain region that is involved in the neural representation of somatic aspects of emotional states and interoception of feeling states. State reexperiencing was negatively correlated with activation of the rostral portion of the anterior cingulate cortex, a brain region involved in arousal and emotion regulation. These findings are consistent with the phenomenology and clinical presentations of PTSD patients who exhibit pathological emotional undermodulation during reexperiencing states, including a variety of negative emotional states and associated bodily experiences.

Emotional overmodulation: excessive corticolimbic inhibition

In contrast to the reexperiencing/hyperaroused subtype, patients with dissociative PTSD exhibit abnormally high activation in brain regions involved in arousal modulation and emotional regulation, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the medial prefrontal cortex. The dissociative PTSD patients can be conceptualized as experiencing emotional overmodulation in response to exposure to traumatic memories. This can include subjective disengagement from the emotional content of the traumatic memory through depersonalization or derealization responses, mediated by midline prefrontal inhibition of the limbic regions.

Dimensionally, dissociative response to trauma reminders is negatively correlated with right anterior insula activation and positively correlated with activation in the medial prefrontal cortex and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (

21). In motor vehicle accident-related PTSD, the medial prefrontal cortex cluster that was positively correlated with state dissociative symptoms was negatively correlated with amygdala activity during script-driven imagery (

26). This finding provides support for hypothesized hyperinhibition of limbic regions by medial prefrontal areas in states of pathological overmodulation, i.e., during dissociative states in response to trauma-related emotions.

A recent study by Felmingham et al. (

27) gives further support to the notion of distinct dissociative and nondissociative reactions in PTSD, based on the corticolimbic inhibition model. Using fMRI, these investigators examined the impact of dissociation on fear processing in two groups of PTSD patients, one with high and the other with low dissociation scores. Felmingham et al. (

27) compared brain activation during the processing of consciously and nonconsciously perceived fear stimuli. Patients with dissociative PTSD showed enhanced activation in the ventral prefrontal cortex during conscious fear processing, relative to patients with nondissociative PTSD. The authors suggest that these data support the theory that dissociation is a regulatory strategy invoked to cope with extreme arousal in PTSD through hyperinhibition of limbic regions, with this strategy most active during conscious processing of threat. A model of the two subtypes of PTSD is presented in

Figure 1.

Additional evidence for hyperinhibition of the limbic system, including the amygdala, during dissociative states stems from the pain neurobiology literature. In a study examining healthy subjects, Roeder et al. (

28) found decreased amygdala activity in response to painful stimulation during hypnosis-induced states of depersonalization. These findings are also consistent with amygdala deactivation in response to thermal pain stimuli in patients with PTSD as well as with borderline personality disorder patients who generally show high levels of dissociation (

29–

31). A recent study revealed a similar pattern of increased mid-cingulate and insula activation in patients with borderline personality disorder and comorbid PTSD in conjunction with reduced pain sensitivity during script-induced dissociative states (

32).

Experimental studies examining emotional memory suppression in healthy subjects provide additional support for the model that dissociative PTSD involves hyperinhibition of limbic regions with memory suppression associated with increased frontal and decreased hippocampal activity (

33). Here, a complex neural network appeared to be involved actively in top-down memory suppression, including dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann's area [BA] 45/46); anterior cingulate cortex (BA 32); the contiguous presupplementary motor area (BA 6); a lateral premotor area in the rostral portion of the dorsal premotor cortex (BA 6/9); and the intraparietal sulcus (BA 7) (also in bilateral BA 47/BA 13 and right putamen). In addition, memory suppression was significantly associated with bilateral hippocampal inhibition. The authors conclude that their study provides a possible neurobiological model for suppression of unwanted memories, consistent with the occurrence of dissociative amnesia (

33).

The aforementioned findings, supporting the corticolimbic inhibition model of dissociative PTSD, are consistent with the phenomenology and clinical presentation of patients with dissociative PTSD. Many of these patients require therapeutic approaches that help them to overcome pathological overmodulation of traumatic memories, associated emotions, and bodily experiences. The corticolimbic inhibition model postulates that once a threshold of anxiety is reached, the medial prefrontal cortex inhibits emotional processing in limbic structures (the amygdala), which in turn leads to a dampening of sympathetic output and reduced emotional experiencing (

34). Several studies in PTSD patients show that the prefrontal cortex has inhibitory influences on the emotional limbic system. These include PET studies showing a negative correlation between blood flow in the left ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala during emotional tasks (

26), and negative correlations between medial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala during fear conditioning (

25). Therefore, the low activation of medial prefrontal regions described in the reexperiencing/hyperaroused PTSD subgroup is consistent with failed inhibition of limbic reactivity. This is associated with emotional undermodulation. In contrast, in the dissociative subgroup, increased activation of medial prefrontal structures is consistent with the notion of hyperinhibition of those same limbic regions. This results in states of pathological emotional overmodulation in response to trauma-related emotions. "Successful" emotional overmodulation appears to involve transient psychological disengagement from trauma-related information. This is marked by alterations in perception and consciousness, as found in depersonalization and derealization states and in dissociative amnesia. Figure 1 summarizes these findings in each subtype of PTSD by contrasting brain regions involved in the reexperiencing/hyperarousal (undermodulation) and dissociative (overmodulation) types of emotional dysregulation to trauma-related stimuli, respectively.

Indeed, this model resembles the signs and symptoms of response to a stressful life event that were originally described by Lindemann (

35) and Horowitz (

36) in their classic works on stress response syndromes. Horowitz suggested that the responses to stressful life events were expressed in two predominant states. The first was an intrusive state characterized by intrusive feelings and compulsive action. The other was a state of denial marked by dissociative symptoms such as emotional numbing and constriction of ideation. The core problem in PTSD, from his point of view, is under- or overmodulation of affective response to traumatic memories—the emotion modulation system cannot adequately regulate effects of extreme traumatic input.