Chronic mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are among the most disabling illnesses worldwide (

1,

2). Neurocognitive impairment is widely recognized as a primary factor in causing and maintaining disability in schizophrenia (

3). Recent research has suggested that the relationship between neurocognition and real-world psychosocial outcomes is largely indirect, mediated by variables such as everyday living skills, social competence, social cognition, symptoms, intrinsic motivation, and metacognition (

4–

9). Thus, neurocognitive impairments are important predictors of functional impairments in schizophrenia, but most of the association with real-world behaviors flows through their relationship with higher-order adaptive skill sets.

In contrast to the large body of research on the neurocognitive and psychopathological determinants of functional outcomes in schizophrenia, substantially less information is available about the characteristics that contribute to the poor functional outcomes observed in bipolar disorder (

10,

11). Two large prospective studies (

12,

13) indicated that depressive symptoms are more frequent, and are correlated with greater functional impairments, than manic symptoms. Psychotic symptoms also contribute to disability, although they are not as prevalent in bipolar disorder as in schizophrenia (

14). In recent years, research has indicated that impairments in sustained attention, verbal memory, and executive functioning appear to persist in the absence of mood episodes (

15) and are related to indices of social and vocational functioning (

16–

22). However, the relative and combined contributions of neurocognitive abilities and symptoms to either functional competence or community functioning are unclear.

Studies of functioning in bipolar disorder are limited by their reliance on subjective ratings of functioning, such as self-report measures, which have questionable validity in both disorders (

23,

24) and may be influenced by current mood state (

25). Furthermore, reliance on categorical milestones, such as employment, marriage, and independent living, may be limited by socioeconomic status and other contextual influences, such as availability of jobs, ethnicity, and disability compensation status (

26,

27). Some societies provide such significant social support that ability measures have no correlation with outcome (

28). Thus, investigators are increasingly relying on more objective measures, such as performance-based assessment of functional capacity and third-party ratings of functional behavior, to provide objective estimates of functional competence and functional outcomes, respectively. To date, results from studies of patients with schizophrenia suggest that these competence measures mediate the relationship between neurocognitive impairment and observer-rated functional impairment (

29). The few studies that employed performance-based measures of functional competence in bipolar disorder (

30,

31) converge to suggest that neurocognition is a stronger predictor of functional competence than symptoms. However, these studies were based on samples of middle-aged and elderly participants and did not assess relationships to real-world disability measures.

In this study, we extend to bipolar disorder our previous findings on schizophrenia, which suggested a relationship between neurocognition and real-world behavior that is largely mediated by functional competence. We also expand the schizophrenia literature to a more age-diverse sample of outpatients.

Method

Participants

To be included in the study, participants had to have a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (the bipolar disorder group; N=130) or of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (the schizophrenia group; N=161), based on a structured interview, and had to be living in the community. All participants were enrolled in a genetic study of schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder conducted by the Epidemiology-Genetics Program in Psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Current clinical symptom severity and mood state were not among the inclusion or exclusion criteria.

The sample was restricted to full or mixed Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry (determined from the ancestry of four grandparents) in order to obtain a sample with high genetic homogeneity. Initial recruitment was conducted nationally through advertisements in newspapers and Jewish publications, talks given at community centers and synagogues, and the Epidemiology-Genetics Program web site (

32). Patients participating in the genetic studies were directly assessed (largely in their own homes) by skilled clinicians (doctoral-level psychologists) using the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (

33). Additional information from medical records, informant reports, and the Family Interview for Genetics Studies (

http://zork.wustl.edu/nimh/home/m_interviews.html) was independently reviewed by at least two clinicians (a Ph.D.-level psychologist or a psychiatrist) before a consensus was formed on DSM-IV diagnoses and on various clinical indicators.

Recruitment and data collection methods were identical for both diagnostic groups. Participants from the parent genetics study were recruited via telephone and letter to participate in the present study and, after providing written informed consent, were assessed in their own homes by members of the original team of clinical examiners using a battery of commonly used neuropsychological tests.

Independent Variables

Neurocognitive composite score.

The neurocognitive battery included commonly used measures of verbal declarative memory, attention, verbal working memory, executive functioning, processing speed, and verbal fluency. We calculated a composite neurocognitive score using equally weighted standardized scores (z scores; mean=0, SD=1) that were derived from normative data from the manuals for each instrument. The composite neurocognitive score included eight variables: total learning from trials 1 through 5 on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (

34), total time to complete Part A and Part B of the Trail Making Test (

35), number of correct responses on the letter-number span test from the WAIS (

36), perseverative errors standard score from the 64-card computerized Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (

37), number of correct responses on the WAIS digit symbol coding test, total unique correct responses on a semantic fluency test (

38), and dr (a signal detection measure) from the Continuous Performance Test–Identical Pairs Version, 4-digit condition (

39). The Cronbach alpha value for the composite score was 0.84, indicating good internal consistency. We also examined differences between groups in estimated premorbid intelligence using the reading subtest of the Wide-Range Achievement Test, 3rd Edition (

40).

Psychopathology measures.

We assessed depressive symptoms with the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI; 41). A total depressive symptoms score is created by summing the 21 items of the instrument (range=0 to 63).

The Profile of Mood States–Bipolar Form (

42) provided an index of the severity of manic symptoms. This self-report of current mood asks the participant to rate 72 items on a 4-point Likert scale (“much unlike this,” “slightly unlike this,” “slightly like this,” and “much like this”). Raw scores were converted to T scores from normative data found in the manual. The total scale T score was used as the mania variable, with higher scores indicating more severe manic symptoms. (The T scores are presented relative to the psychiatric outpatient sample, not a healthy comparison sample.)

Severity of positive and negative symptoms was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; 43). This 30-item scale, which contains seven items measuring positive symptoms, seven items measuring negative symptoms, and 16 items measuring general aspects of psychopathology, was completed after a structured interview by a psychologist and a structured interview with an informant. We used the positive and negative domains from the empirically derived five-factor model of the PANSS (

44).

Proposed Mediators

We examined adaptive competence and social competence independently to observe whether they contributed differentially to the prediction of diverse outcomes. These measures had overlap (r

2=0.37) consistent with the correlation between the University of California San Diego [UCSD] Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA; 45) and neurocognitive performance in our previous research (

4,

5). The magnitude of this correlation suggests that these two ability areas are related but separable areas of functional skills.

Adaptive competence.

We refer to adaptive competence as those instrumental skills that are important for functioning independently (

46). An adaptive functional competence variable was created from an equally weighted composite of the UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment–Brief Version (UPSA-B; 45) and the advanced finances test from the Everyday Functional Battery (EFB; 47); we call this composite measure the UPSA-B/EFB. In the UPSA-B, respondents are asked to role play tasks in two areas of everyday functioning: communication and finances. The total raw score ranges from 0 to 20. In the advanced finances test, participants perform higher-level financial management skills than in the UPSA, including depositing a check, paying three bills (including only a portion of the credit card bill in order to leave money in the account), and balancing a checkbook. Raw scores range from 0 to 17. The composite adaptive functional competence variable had adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.87). It was converted to a standard score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better adaptive competence.

Social competence.

Social competence (i.e., paralinguistic and verbal behaviors necessary for communication) was assessed with the Social Skills Performance Assessment (

48). After a brief practice, participants initiate and maintain a conversation for 3 minutes in each of two situations: greeting a new neighbor and calling a landlord to request a repair for a leak that has gone unfixed. Affect and grooming are rated in person by the examiner; all other variables, such as interest, fluency, clarity, focus, negotiation ability, submissiveness/persistence, and social appropriateness, were rated via audiotape by an off-site trained rater who was unaware of the study design, diagnosis, and all other data. We used the mean item score on these variables for both scenes as the social competence variable, with higher scores indicating better social competence.

Outcome Variables

The Specific Level of Functioning Scale (

49) was used to rate real-world functional outcome. This 43-item observer-rated scale measures the following domains: interpersonal relationships (e.g., initiating, accepting, and maintaining social contacts; effectively communicating), participation in community and household activities (shopping, using the telephone, paying bills, using public transportation), and work skills (e.g., employable skills, level of supervision required to complete tasks, punctuality, ability to stay on task and complete tasks). Note that the work skills domain comprises behaviors important for vocational performance but is not a rating of behavior during employment. Ratings by the third-party informant are made on the basis of the amount of assistance required to perform real-world skills or frequency of the behavior. Raters were selected who were familiar with the participant's functioning (e.g., family members, friends, case managers). If such individuals were unavailable, the examiner rated this information from his or her own observations of and interactions with the participant. Twelve percent of the schizophrenia group and 13% of the bipolar disorder group were rated by the examiner on the Specific Level of Functioning Scale. We ran multivariate analyses of variance for each group to determine whether there were differences on the three variables of instrument for those who were rated by an examiner. There were no statistically significant differences for either group on any of the subscales or demographic variables (all p values >0.05).

Statistical Analysis

We tested the direct and indirect predictors of the Specific Level of Functioning Scale real-world outcome domains with confirmatory path analyses in the separate diagnostic groups. Based on previous research (

8,

9), we predicted that neurocognition, the empirically derived positive and negative symptom domains, and the total scores from the BDI and the Profile of Mood States–Bipolar Form as exogenous variables (i.e., variables that are not predicted directly by other variables) would predict each of the real-world outcome domains. The two competence measures, the UPSA-B/EFB (adaptive competence) and the Social Skills Performance Assessment (social competence), were hypothesized as mediating neurocognition but not symptom variables.

The final models were developed within each sample through an iterative procedure in which statistically nonsignificant paths with the smallest contribution to the outcome variable were sequentially eliminated from a saturated model (in which all variables are interrelated) until the best-fitting model was identified, defined by three different goodness-of-fit statistics: the model chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A good-fitting model is reflected by nonsignificant chi-square tests, a CFI greater than 0.90, and an RMSEA less than 0.08. The chi-square test is a comparison of the observed covariance matrix to the covariance matrix of the final model. The CFI compares the final model with an “independence model” and indicates the percent to which covariation in the data is replicable. The independence model is a null model that assumes that all variables are uncorrelated with the dependent variable. The RMSEA is a model fit measure that accounts for model complexity, thus promoting the most parsimonious model by considering degrees of freedom.

Diagnostic comparisons of the strength of neurocognition's direct and mediated path coefficients for the competence and real-world performance measures were performed by testing for the significance of the difference between coefficients. The total causal effects for the real-world measures were determined with effects decomposition, where indirect effects are the factor of the coefficient from neurocognition to the competence measure and the competence measure to real-world behavior. The total causal effect is the sum of all indirect effects and the direct effect.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics, test performance results, and functional ratings of the two groups are presented in

Table 1.

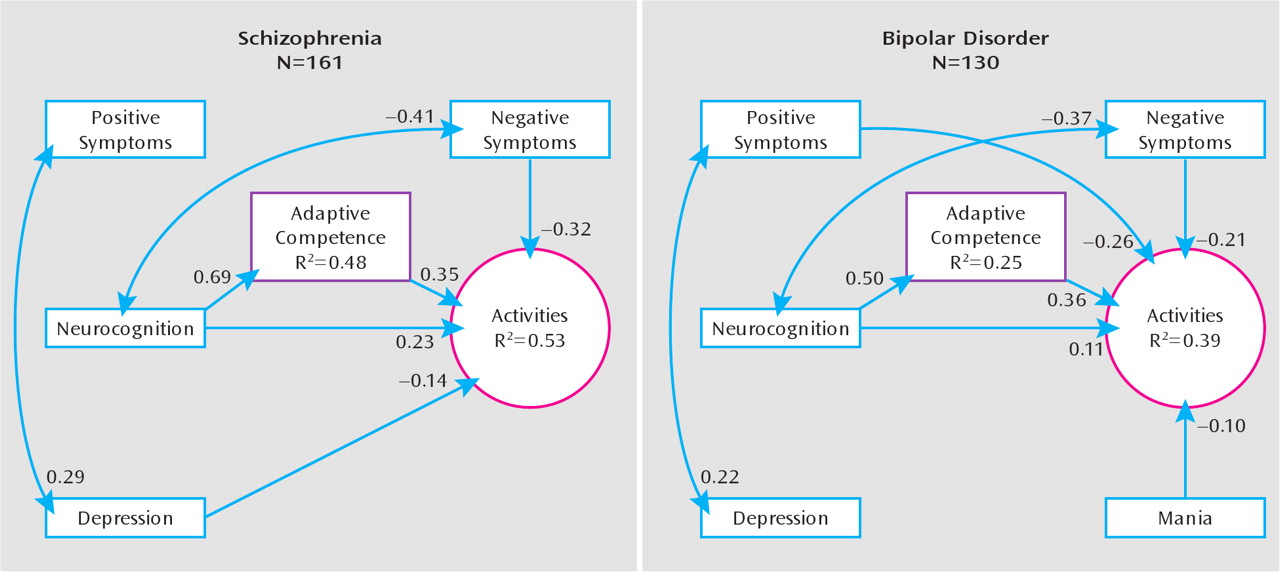

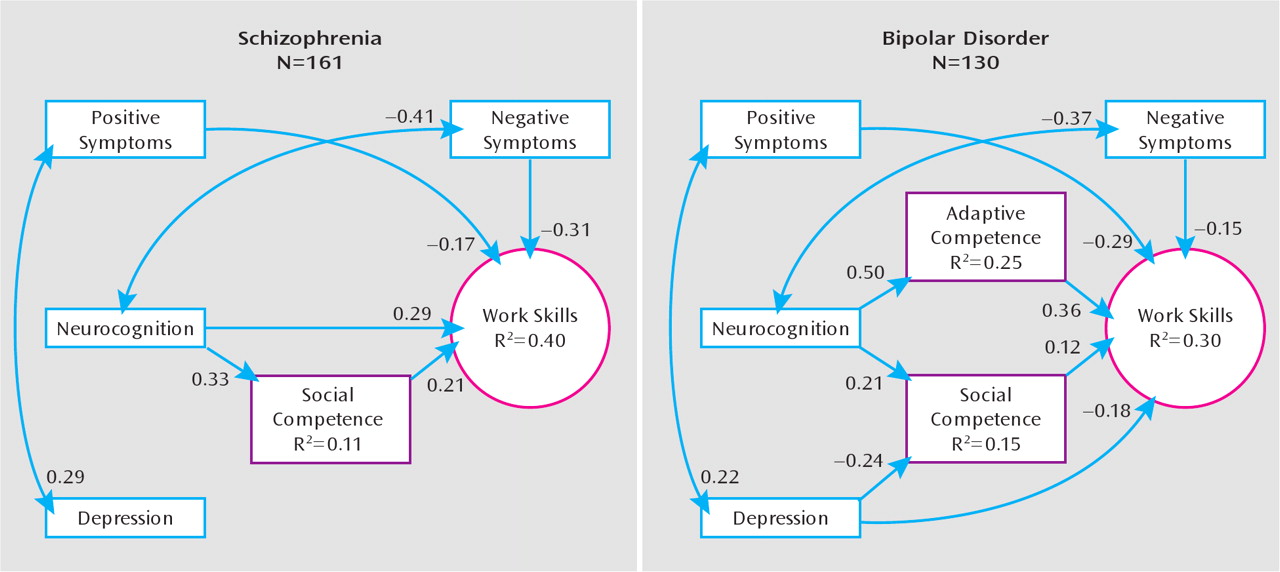

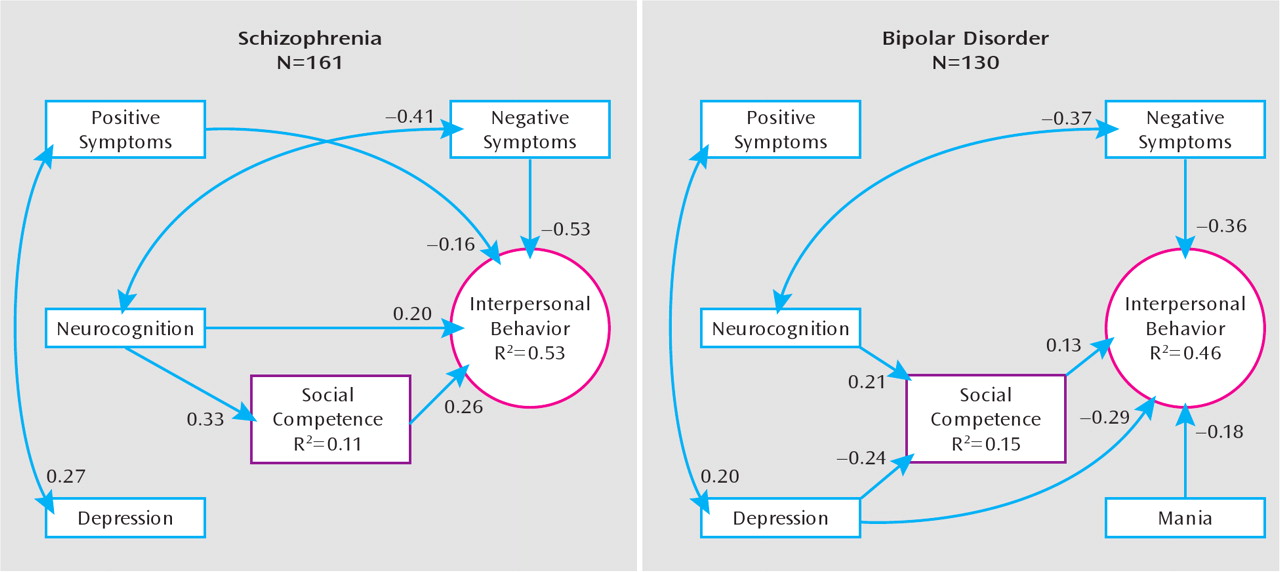

The final models produced adequate fit statistics for both groups across all three real-world outcome domains (

Table 2). Neurocognition was associated with both competence variables, but only depressive symptom severity was associated with either competence variable. In both groups, neurocognition was related to activities (

Figure 1; schizophrenia group, R

2=0.53; bipolar disorder group, R

2=0.39) directly and through a mediated relationship with adaptive competence. Negative symptoms and depressive symptom severity were negatively associated with activities in the schizophrenia group, and positive, negative, and manic symptoms were negatively associated with activities in the bipolar disorder group. Work skills (

Figure 2; schizophrenia group, R

2=0.40; bipolar disorder group, R

2=0.30) were directly and indirectly (through mediation with social competence) predicted by neurocognition in the schizophrenia group, and neurocognition's association with work skills in the bipolar disorder group was mediated entirely by adaptive and social competence. Positive and negative symptoms were negatively associated with work skills in both groups; depressive symptoms further predicted poor work skills in the bipolar disorder group. Interpersonal relationships (

Figure 3; schizophrenia group, R

2=0.53; bipolar disorder group, R

2=0.46) were predicted indirectly (through social competence) by neurocognition in both groups and directly by neurocognition, positive symptoms, and negative symptoms in the schizophrenia group. In the bipolar disorder group, interpersonal relationships were predicted by manic symptoms and by depressive symptoms, the latter of which had both a direct and a mediated (through social competence) relationship.

The test for significant differences between coefficients revealed significant differences between the two diagnostic groups in the strength of the relationship of neurocognition with competence measures and real-world behavior. In the activities domain, the direct relationship of neurocognition was not significantly different between the groups, but the total causal effect (direct plus indirect effects) was significantly larger in the schizophrenia group (standardized regression coefficient β=0.47) compared with the bipolar disorder group (β=0.29) (p=0.038). In this model, the strength of the path from neurocognition to adaptive competence was stronger in schizophrenia (p=0.006). Neurocognition was not a direct predictor of work skills in the bipolar disorder group, and its total causal effect in this group (β=0.20) was lower than in the schizophrenia group (β=0.36), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.07). The relationship of neurocognition with social competence was not significantly different between diagnostic groups (p=0.14). Interpersonal behavior was not directly predicted by neurocognition in the bipolar disorder group, and its total causal effect (β=0.027) was lower than in the schizophrenia group (β=0.29) (p=0.01).

Discussion

The results of this study expand previous findings that modeled the direct and indirect relationships among measures of neurocognition, symptoms, functional competence, and everyday outcomes in patients with schizophrenia and show further that the model largely generalizes to patients with bipolar disorder. The relationships between neurocognition and functioning include both direct relationships and relationships mediated by adaptive and social competence. In contrast, clinical symptoms (with the exception of depressive symptoms) were related to functioning in the community but not with competence, which suggests that the effects of positive, negative, and manic symptoms on everyday behaviors might occur at a postcompetence level, not affecting the ability to perform skilled acts yet influencing the likelihood of performing them. These findings converge to suggest that we might observe persistent functional disability in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder even after they cross traditional thresholds for treatment success (such as a given percentage reduction in positive symptom severity) as a result of neurocognitive and skill deficits. Conversely, even if a patient acquires certain skills but continues to experience mild levels of core (positive and negative) and nonspecific (depressed) symptoms, changes in real-world behavior might lag or not manifest at all.

Our results suggest that the paths from clinical factors to real-world disability are consistent in a number of important ways between patients with schizophrenia and those with bipolar disorder, even when there are differences between disorders in the severity of real-world deficits. Neurocognition clearly has an important role in functional outcomes across both disorders, although the direct and total effects are larger in schizophrenia. In contrast to a previous study with older schizophrenia patients (

4), in this study we found more evidence for direct effects of neurocognition on work skills and interpersonal behavior, perhaps related to the greater age range of our sample or the larger sample size. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined whether functional competence measures mediate the link between neurocognition and disability in bipolar disorder. Our data suggest that the mediation role of these measures in bipolar disorder may actually be more pronounced than in schizophrenia, with most of the relationship between cognition and real-world outcomes mediated by competence. Thus, the path from neurocognitive deficit to functional disability is stronger and more direct in schizophrenia but still quite relevant in bipolar disorder.

The role of symptoms in predicting disability was significant, but it was generally unmediated by competence measures and was somewhat different in bipolar disorder compared to schizophrenia. Similar to previous studies—and not surprising given their diagnostic importance—depressive and manic symptoms were associated with real-world functional performance deficits in bipolar disorder, with manic symptoms having an inverse relationship with activities in the home and community, depression negatively associated with work skills, and both types of mood symptoms associated with poorer interpersonal behavior. Similar to previous reported findings on bipolar disorder (

12,

13), depressive symptoms were stronger predictors of poor outcomes than manic symptoms. The positive symptom associations with outcomes in this bipolar disorder sample might indicate that positive symptoms, although less frequent and severe in bipolar disorder, are more disruptive when present in this condition, which typically has a more cyclical manifestation of psychosis. Negative symptoms are infrequently reported in the bipolar disorder literature, which limits our ability to interpret the present findings. It is unlikely that the relationship is an artifact of measurement overlap with depressive symptoms; total scores for depression and negative symptoms had a small, nonsignificant relationship in this sample, and previous work (

50) has indicated that measurement of depressive symptoms with the BDI does not substantially overlap with negative symptoms.

The present findings are supported by other reports that suggest that depressive symptoms are an important predictor of disability in bipolar disorder (

12,

51). An interesting deviation across the two diagnostic groups was the path from symptoms of depression to real-world outcomes. In bipolar disorder, but not schizophrenia, depression was associated with social competence, and its relationship with interpersonal behavior and work skills was partially mediated by this relationship. Thus, in bipolar disorder, depressive symptoms may serve as a potential rate limiter of real-world behavior and also as a phasic suppressor of social skills. Alternatively, poor social skills may produce a vulnerability to depression. It would be important for future research to investigate the intraindividual trajectories of social skills and depression in bipolar disorder to understand the direction of causal relationships. Such knowledge would be useful in adapting rehabilitation approaches to bipolar disorder.

There are several limitations to this study. The sample was restricted to a culturally homogeneous group. Participants were outpatients and on average were experiencing mild symptoms. Therefore, the generalizability of these findings to ethnically diverse populations, to inpatients, and to more acutely ill patients is limited. Some studies (e.g.,

reference 20) have demonstrated relationships of specific neurocognitive domains to functional deficits that differed by diagnosis; although our sample size was considerable, it was not sufficiently powered to evaluate each neurocognitive test individually in the statistical procedure used. For some individuals with bipolar disorder, there will be a ceiling effect for the functional competence and outcome domains, and future research should determine how sensitive these and other measures are for the more subtle functional deficits. Additionally, it will be important to assess more domains of functioning and to continue to search for optimal methods for assessing disability in chronic mental disorders. As in efforts to refine our assessment of outcomes in schizophrenia (

52), our understanding of the severity and predictors of disability in bipolar disorder would be enhanced by similar endeavors. Finally, this study was cross-sectional; further work examining the sources of intraindividual variability in functional abilities over time is needed to ascertain causal effects of illness characteristics on long-term functioning outcomes.

In summary, our findings indicate that multivariate path models linking neurocognitive ability, functional competence, and symptoms with real-world functional performance confirm previous models in schizophrenia and generalize to bipolar disorder. Disability is multiply determined, with the effect of neurocognition mediated by functional capacity and a separable and more direct effect of symptoms. Differences between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder lie largely in the strength of the relationships and which symptoms most influence disability, and our study reaffirms the broad debilitating role of bipolar depression in maintaining disability. These results suggest that recent advances in measurement of cognitive and functional abilities in schizophrenia may be quite relevant to measurement of disability and related rehabilitative efforts in bipolar disorder. As opposed to schizophrenia, there has been little emphasis on pharmacological or nonpharmacological cognitive remediation in bipolar disorder, and there have been few examples of rehabilitative programs aimed at functional skills in patients with bipolar disorder (

11). Our results support the suggestion that models for cognitive rehabilitation under way in schizophrenia (

53) should be adapted for bipolar disorder (

54).