Conversion disorder as defined in DSM-IV describes symptoms such as weakness, seizures, or abnormal movements that are not attributable to a general medical condition or to feigning and that are judged to be associated with psychological factors. As somatoform disorders are overhauled in DSM-5 (1), it is a good time to reconsider both the name and criteria for this diagnosis.

The name "conversion disorder" refers to a hypothesis based on psychoanalytic etiology. Although long dominant, the conversion hypothesis is now just one of many competing etiological hypotheses and has little supportive empirical evidence. Even the notion that the etiology of these symptoms is wholly psychological may be scientifically incorrect. For example, functional brain imaging studies showing findings such as contralateral thalamic hypoactivity in hemisensory conversion encourage us to understand conversion symptoms from a brain as well as mind perspective (2). Furthermore, the name "conversion disorder" has not been widely accepted by either nonpsychiatrists or patients (3, 4). We therefore need a name that sidesteps an unhelpful brain/mind dichotomy, will be more widely used clinically, and will be more accepted by patients (5). We suggest that the term "functional neurological disorder," as a diagnosis for symptoms such as "functional weakness," would be practically and theoretically more useful (6). This would be a return to an older terminology that is in keeping with the concept of functional somatic symptoms (7).

The current DSM-IV criteria require the positive exclusion of feigning. Proving feigning is difficult enough; proving the absence of feigning is arguably impossible. They also require the identification of psychological factors associated with symptom onset. Although the diagnostic stability of the neurological symptoms has been confirmed (8), these "psychological" criteria have not been shown to be either diagnostically reliable or predictive of outcome (9). For the majority of patients psychological factors can be identified, but not for all. Even when psychological factors are identified, there are no clear methods for determining whether they are etiologically relevant.

In practice, conversion disorder is usually diagnosed after a neurologist has identified a symptom as "nonorganic" because of clinical findings of incongruity with disease or internal inconsistency (6). For example, functional leg weakness can be demonstrated objectively when weakness of hip extension disappears during contralateral hip flexion against resistance (Hoover's sign). Functional arm tremor is suspected when a tremor disappears during voluntary rhythmical movement of the unaffected arm. A final example is a seizure-like event with simultaneous normal video EEG. The DSM-IV criteria currently require the exclusion of disease but do not refer to these useful diagnostic procedures. We suggest that incorporating physical diagnostic features observed in conversion disorder in the criteria would improve psychiatric understanding and confidence in the diagnosis.

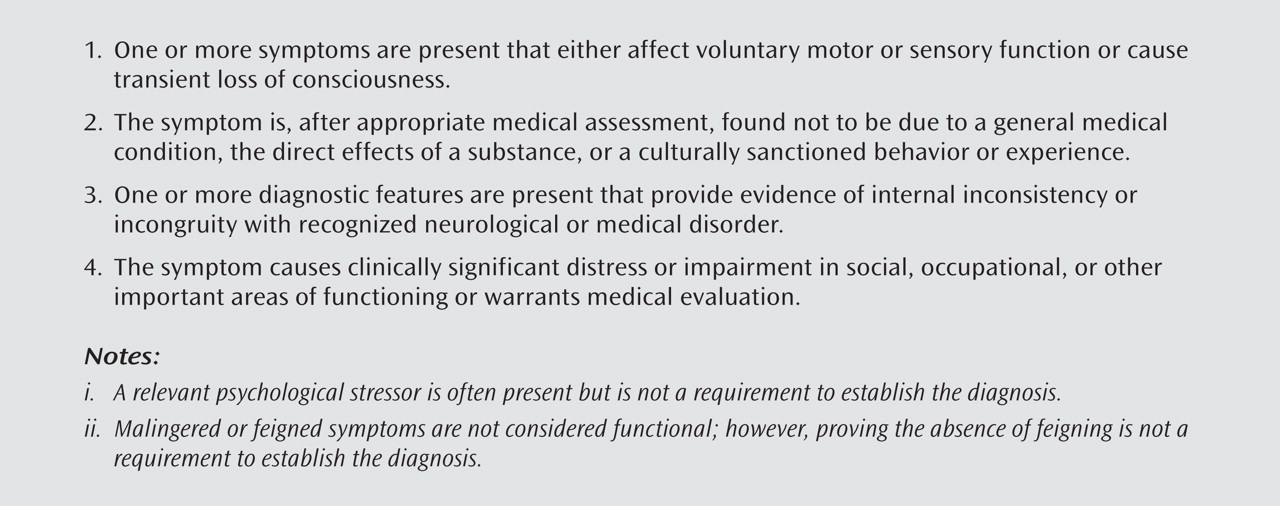

In summary, we suggest that conversion disorder be renamed "functional neurological disorder" and that the requirement for the exclusion of feigning and identification of associated psychological factors be relegated to the accompanying text. We suggest that discriminating clinical features be given greater prominence (

Figure 1). Together these changes have the potential to foster collaboration between psychiatrists and neurologists, which is critical to improving both the understanding and care of this neglected group of patients.