The complex relationship between depression and coronary heart disease affords unique opportunities for psychiatrists to improve their patients' future well-being. This issue of the

Journal contains an article by Duivis et al. clarifying the interconnections among depression, inflammation, and health behaviors such as smoking, physical activity, and obesity (

1). The article is from the Heart and Soul Study, a large prospective cohort of 1,024 patients with coronary heart disease in the San Francisco Bay area that examines psychosocial factors and health outcomes. Like the historic Framingham Study, the Heart and Soul Study follows patients over time, tracking depression, inflammatory markers, and heart disease outcomes. The study reported by Duivis et al. followed 667 patients—an 80% sample of the 829 Heart and Soul Study survivors—for 5 years, exploring the realities that depression is much more common in those with heart disease and is associated with worse cardiac outcomes and also higher markers of inflammation. The two questions posed were “Which came first, inflammation or depression?” and “Did health behaviors serve as a mediating factor?”

Depressive symptoms were measured by a 9-item patient health questionnaire—initially in person; by phone in years 1, 2, 3, and 4; and again in person at year 5. Responses were divided into three categories: no depression (443 patients), depression at one interview only (N=86), and depression at two or more interviews (N=138). Three inflammatory biomarkers—C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and fibrinogen—were measured at baseline and after 5 years. Three health behaviors associated with inflammation were measured: smoking status (yes or no), physical activity (divided into six categories), and body mass index. Increases in inflammatory factors are believed to mirror endothelial inflammation in damaged coronary arteries as well as increased adhesiveness of blood platelets, both of which promote intra-arterial thrombosis.

The results confirmed high levels of depression among patients with coronary heart disease. Depression predicted subsequent inflammation—but not vice versa. But after further adjustment for health behavioral factors, the association was no longer significant. In other words, health behavioral factors associated with depression were what seemed to cause inflammation in depressed cardiac patients, rather than the depression itself. Patients with more persistent depression had higher subsequent levels of inflammatory markers, but this association was also fully explained by health behaviors. Finally, high initial levels of inflammation did not predict subsequent depression.

Smoking was defined only as a dichotomous variable, but since the effects of smoking on inflammation and endothelial markers appear at very low doses (

2), one would not expect much of a dose-response curve for smoking. Physical activity was defined by self-report and may thus have been overstated. But there is no reason to expect selective overreporting. We do not know whether those with depressive symptoms received treatment for that condition. And as acknowledged by the authors, this population is mainly composed of older men, and thus the results may not generalize to other populations.

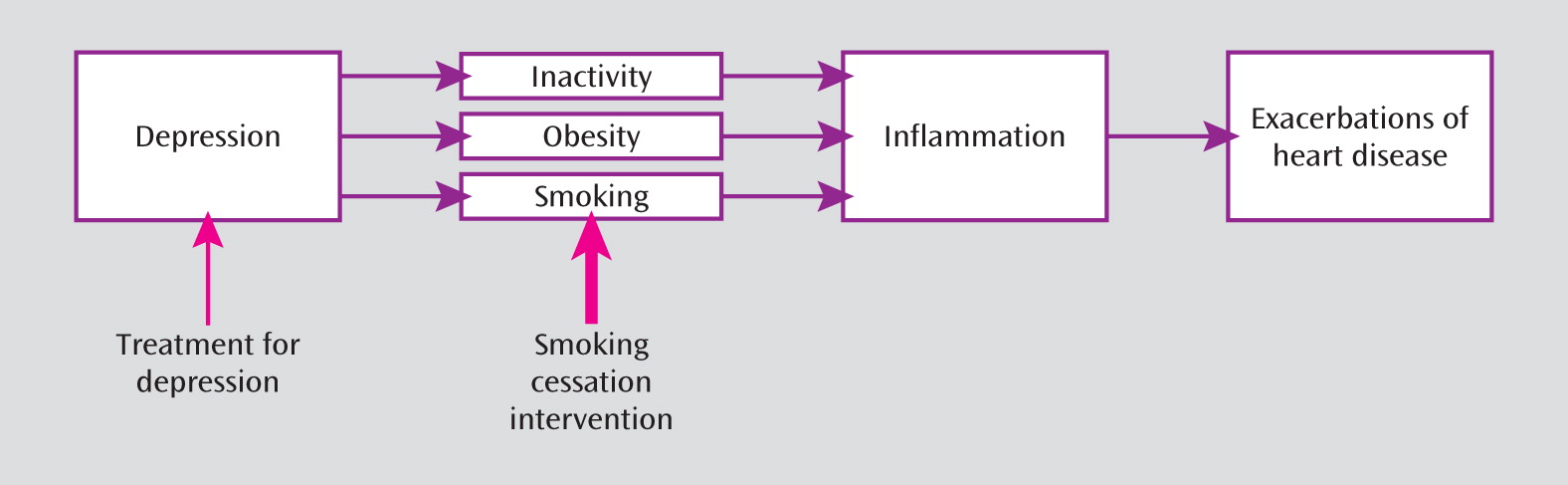

These results suggest three ways that clinicians can reduce the risk of heart disease among patients with depression, some more evidence-based than others (

Figure 1). First, they can treat depression. Second, they can encourage their patients to be physically active and to help those with obesity to lose weight. The evidence that physicians can achieve major changes in those areas, however, is not as robust as we would wish. Finally, and most important, they can help smokers to quit. A strong body of evidence shows that intercession by physicians increases the chances of smokers quitting and that a combination of medications and counseling can generate quit rates of up to 30%, as opposed to the baseline “cold turkey” rates of 3%–5% (

3). And not only does stopping smoking reduce the risk of heart disease, it also conveys scores of other health benefits, including reducing the risk of cancer, lung disease, stroke, diabetes, and many other diseases (

4).

Persons with psychiatric diagnoses have much higher rates of smoking than the general population, and they smoke more cigarettes than the average smoker. As a result, 44% of the cigarettes consumed in the United States are by persons with mental illness and/or substance use disorders (

5). And those with serious mental illnesses die, on average, 25 years earlier than the general population, with most of those early deaths occurring from tobacco-related diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes, and chronic lung disease (

5).

We are now in the midst of a profound culture change that is denormalizing the use of tobacco in mental health and substance abuse treatment settings (

6). As someone who has tried to stimulate that norm change, through the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center at the University of California at San Francisco, I can report on the reasons for it as well as the many obstacles remaining. Our website (

http://smokingcessationleadership.ucsf.edu) offers a wide variety of tools and information to assist clinicians in helping their patients to stop smoking.

The previous assumptions that have hampered efforts toward smoking cessation are now beginning to fall under the weight of accumulating evidence. “These patients do not want to quit.” In fact, they do, and at rates (70%–80%) comparable to those in the general population (

3,

5). “They are not able to quit.” But many do, and with only slightly less success than the general population (

7). “If they quit, their mental health or substance abuse conditions will worsen” (

8). Recent research has called that assumption into question. Mental health conditions can be stable or even improve (

5,

9), alcoholics who stop smoking are more likely to stay sober (

5), and hospital wards that go smoke-free have fewer aggressive incidents and more staff time freed up for therapeutic encounters (

5). Psychiatrists not familiar with smoking cessation may ask if it is worth the effort, compared, for example, to the 33% remission and 47% response rates of treating depression with an SSRI (

10). Given that smoking causes half of smokers to die prematurely, and often with a miserable terminal illness, even a small decrease in smoking rates would be worth the investment. The published range of successful quit rates, from 10% to 30%—with one study showing a 1-year 50% quit rate for depressed patients—greatly exceeds the 3%–5% success rate from unaided cessation (

3,

5). Thus, although many cessation attempts will fail, the benefits are so great as to be worth the effort.

Psychiatric nurses have embraced this culture change by adopting the position that all nurses should become smoking cessation advocates and that increasing numbers will become smoking cessation experts (

11). Psychiatrists should do the same. If possible, incorporate smoking cessation counseling into regularly scheduled sessions with mental health professionals. When prescribing antidepressive medications to a smoker, consider bupropion, which is effective in reducing nicotine craving (

3). Do not hesitate to recommend nicotine replacement therapy. It is safe, even in patients with cardiac disease (

3). And be comforted by the fact that many new studies contradict the previous assumption that smoking cessation might cause suicide in depressed patients (

5,

8). When faced with a patient who smokes, there are three acceptable responses: treat the patient yourself, according to the best evidence (

4); refer the smoker to a smoking cessation treatment facility; or refer the patient to a toll-free telephone “quitline,” accessed through 1-800-QUITNOW, which is an alternative currently successfully used by many depressed smokers. The fourth alternative, doing nothing, is now unacceptable.