With over 1 million suicides per year worldwide, suicide is a major public health problem. It is well established that suicide has a heterogeneous and multidetermined etiology. Family studies, including adoption, twin, and high-risk designs, have shown familial transmission of suicidal behavior. In a case-control study of 57 adoptee suicides from the Danish Adoption Register, Schulsinger et al. (

1) observed a sixfold increase in suicide risk in the biological relatives of adoptees who died from suicide as compared with the biological relatives of living adoptee comparison subjects. This finding supports a genetic rather than an environmental effect on offspring suicide risk; however, the study did not specifically focus on the child-rearing environment as it included family members other than parents. Twin studies have shown that approximately 43% of the variability of suicidal behavior is attributable to biological or genetic factors and 57% is attributable to environmental factors. The concordance of suicidal behaviors among monozygotic twins is not 100%, which also supports environmental contributions (

2–

5).

High-risk studies, a variant of a family study design that compares the offspring of affected and unaffected parents, have found that the timing of parental suicide is relevant. Parental suicide during the offspring's childhood or adolescence, but not in young adulthood, increases the risk of suicide among offspring (

6). This evidence could provide support for the developmental or environmental impact of parental suicide by implying stronger environmental risk after losing a primary caregiver during a critical developmental period. However, greater suicide risk among children who lost a parent to suicide during early childhood may also imply a stronger genetic risk, as their parents may have had severe early-onset mental disorders. High-risk studies cannot disentangle genetic and environmental influences on the transmission of suicidal behaviors.

One challenge in this area of research is how to parse out the unique contributions of the genetic and environmental impact of growing up in the context of parental suicidal behaviors from that of growing up in the context of parental psychiatric illness. Because 90% of suicide attempters and completers had at least one psychiatric disorder at the time of death or attempt (

7,

8), the majority of offspring of suicidal parents are also exposed to parental psychiatric illness. Few, if any, life events are more traumatic for a child than experiencing parental suicide, especially if they witnessed the suicide or found the body. Children adopted early in life may not have directly experienced their biological parents' suicidal behaviors or psychiatric disorders. An adoption study design comparing the adopted offspring of biological parents who had suicidal behaviors (BPSB; defined as suicide or suicide attempt hospitalizations) with the adopted offspring of biological parents who had nonsuicidal psychiatric hospitalizations (BPPH) can help to address the challenges mentioned above.

In this study, we examined the long-term risk of suicide attempt and other psychiatric hospitalizations among adoptees with BPSB and BPPH. We also investigated the influence of an environmental factor (psychiatric hospitalizations of adoptive parents before the adoptees were 18 years old) on the risk for psychiatric hospitalizations of adoptees with BPSB and BPPH. We had the unique opportunity to study how psychiatric impairment in adoptive parents that was severe enough to warrant hospitalization affected adoptee outcomes and to distinguish the risk above and beyond that conferred by having a BPSB. We hypothesized that family environment, indexed as adoptive parents' psychopathology, would interact with genetic risk for suicidal behavior to increase the adoptee's risk for suicide attempt hospitalizations.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the adoptees with BPSB and those with BPPH. Most adoptees were born in Sweden (99% in both groups). The sex representation was almost balanced (52% male in the BPPH group and 51% male in the BPSB group). Adoptees with BPPH were slightly older on average than those with BPSB. The proportion of adoptees with BPSB and BPPH with lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations was similar (17% and 16%, respectively).

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the biological and adoptive parents. The majority of parents were born in Sweden. Adoptive parents were older than biological parents, and lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations were higher in biological than in adoptive parents. For a large proportion of adoptees, data on biological fathers were missing (29% among adoptees with BPPH and 46% among those with BPSB). The biological mothers of adoptees with data missing on biological fathers were not younger than biological mothers with data available on biological fathers. Among the adoptees with data missing for biological fathers, there were few differences between adoptees with BPSB and BPPH, except that those with BPSB were younger.

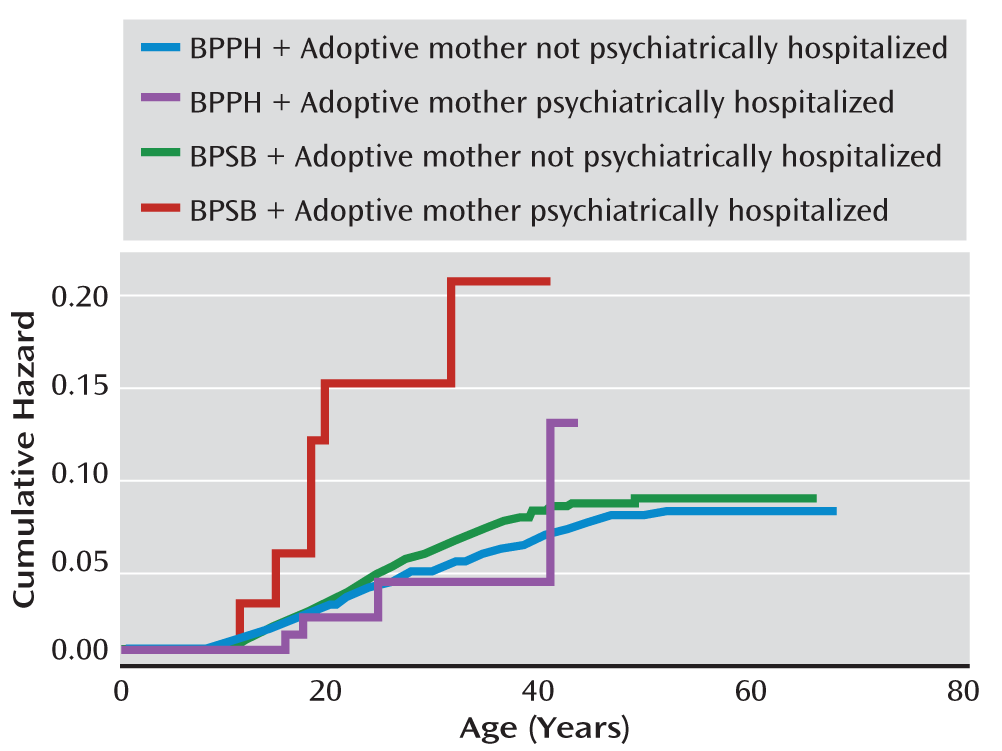

When we examined the risk of suicide and psychiatric hospitalization among adoptees with BPSB relative to adoptees with BPPH, those with BPSB were not at greater risk for any of the outcomes, except for a marginally higher risk for suicide and for drug use disorder hospitalizations (p<0.10 and p>0.05) (

Table 3), after adjusting for adoptee birth cohort and biological mothers' alcohol and drug use disorders. We also compared the risk of adoptee psychiatric hospitalization among those with and without adoptive parents who were psychiatrically hospitalized when adoptees were under age 18. Adopted offspring of psychiatrically hospitalized adoptive parents were at greater risk for hospitalization for unipolar depression (adjusted hazard ratio=1.87, 95% CI=1.10–3.16) and alcohol use disorder (adjusted hazard ratio=1.87, 95% CI=1.19–2.95) (

Table 3,

Figure 1).

Among those with an adoptive mother who was psychiatrically hospitalized when the adoptees were younger than 18, adoptees with BPSB were at greater risk for suicide attempt hospitalizations relative to adoptees with BPPH (adjusted hazard ratio=4.19, 95% CI=1.27–13.77; interaction p=0.04). In contrast, no difference was observed between offspring of BPSB and offspring of BPPH when the adoptive mother was not psychiatrically hospitalized (adjusted hazard ratio=1.15, 95% CI=0.93–1.41). A similar trend was noted for drug use disorder hospitalizations (interaction p=0.06). Adoptees with a psychiatrically hospitalized adoptive mother and BPSB had a greater risk for drug use disorder hospitalization than those with a psychiatrically hospitalized adoptive mother and BPPH (adjusted hazard ratio=4.29; 95% CI=1.17–15.71). However, no difference was observed between offspring of BPSB and BPPH whose adoptive mother was not psychiatrically hospitalized when the adoptees were under age 18 (adjusted hazard ratio=1.20; 95% CI=0.93–1.54).

Discussion

This study found that genetic risk for suicidal behaviors, indicated by having a BPSB, on adoptee's risk for suicide attempt hospitalization was conditional upon the adoptive mother's psychiatric hospitalization during the adoptee's childhood or adolescence. Neither a parental history of suicidal behaviors nor an adoptive mother's psychiatric hospitalization alone placed adoptees at greater risk for suicide attempt hospitalizations, but the interaction of the two factors increased the risk for adoptee suicide attempt more than fourfold. The interaction results were specific to adoptee suicide attempt hospitalizations.

We found marginal statistical significance in the interaction effect of BPSB by adoptive mothers' psychiatric hospitalization on adoptee hospitalizations for drug use disorder, even after adjusting for hospitalizations for drug use disorder in biological mothers. Adoptees who grew up in a home in which an adoptive parent had a psychiatric hospitalization were at greater risk for hospitalization for depression and alcohol use disorder than those adoptees whose adoptive parents were never hospitalized.

These findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. The most prominent is the registers' inclusion of only those suicide attempts and psychiatric disorders that were severe enough to require hospitalization. We could not examine suicide attempts and psychiatric problems that were untreated, that were treated in outpatient facilities, or that occurred before 1973. Therefore, the estimation of the impact of BPSB relative to BPPH on adopted offspring outcomes is subject to some degree of error and likely reflects the operation of these risk factors only for those who display the most severe psychopathology. We did not have data on parent income, education level, employment status, and marital status in our database, and these variables were not adjusted for in the analyses. Our results are limited by the lack of information on specific suicide susceptibility genes or pathways of genetic effect. Only 38 adoptees had both risk factors (BPSB and an adoptive mother with a psychiatric hospitalization while the adoptee was younger than 18), resulting in broad confidence intervals for the interaction term. Generalizability may be limited to the Western world, since the Swedish population is primarily Caucasian and has a relatively high socioeconomic status and universal access to health care. Studies that have examined gene-environment correlation have found that risk can be reciprocal in that the behavioral and psychiatric characteristics of offspring may contribute to parental psychiatric status. We did not examine this correlation in this study.

Limitations of the adoption design include the possibility of range restriction in the adoptive parents because adoptive parents are screened and may enjoy greater financial security and better mental health than the general population. It has been suggested that gene-environment interactions may exist only at the extremes of genetic and environmental variation, and thus our findings may actually be an underestimate of the impact of environmental risk (

13). We do not know the age of the children at the time of adoption, nor do we have data on their circumstances before the adoption. The possibility of selective placement cannot be ruled out in some individual instances. We are missing data on a large proportion of biological fathers, which indicates that a large proportion of mothers (29% among adoptees with BPPH and 46% among adoptees with BPSB) were unwed. This may have resulted in more conservative estimates; some adoptees with BPPH with missing data on their biological fathers may have had fathers with suicidal behaviors. We do not have data on whether adoptees were aware of their biological parents' suicidal behaviors and psychiatric disorders. We did not exclude offspring adopted by relatives, but adoptees with BPSB and BPPH did not differ in the proportion of adoptive parents with psychiatric hospitalizations.

In terms of counterbalancing strengths, this study used a large and nationally representative sample of adoptees. The proposed research was conducted in the context of a 30-year longitudinal and prospective adoption design to disentangle the complex interplay between genes and the environment. The constructs were not biased by self-report, and there were minimal selection, ascertainment, and diagnostic biases. In contrast to many other studies in this domain, we had detailed information on psychiatric hospitalizations of the biological and adoptive parents. We had the ability to stratify by maternal and paternal adoptive parents' psychiatric hospitalizations. This is a major strength, as the impact of fathers' psychiatric status on offspring outcomes is rarely studied. Although we did not observe an impact of adoptive fathers' psychiatric hospitalizations on offspring outcomes, a recent review (

14) found that father engagement positively affects offspring social, behavioral, psychological, and cognitive outcomes.

Family studies have shown that suicidal behaviors cluster in families and are transmitted within families independently of the transmission of psychiatric disorders. Impulsive aggression, defined as the tendency to respond to provocation or frustration with hostility or aggression, appears to be transmitted independently of psychiatric disorders and may be an intermediate phenotype for early-onset suicidal behavior (

15). As our comparison group was characterized by previous psychiatric hospitalizations in biological parents, our findings agree with the literature that suicidal behaviors are transmitted partially independently of psychiatric illness (

16).

Studies of other phenotypes have found that family environment, indexed as adoptive mother's psychopathology, interacts with genetic risk to predict adolescent problem behaviors and adult conduct problems and depression (

17–

19). In contrast, low levels of environmental risk have been found to protect against high genetic risk for substance abuse in a prospective sample of adolescent twins (

20).

One implication of this study is that our studied environmental factor is modifiable and can be targeted for intervention. Weissman et al. (

21) reported that remission of maternal major depression following antidepressant treatment was associated with reduced diagnoses and symptoms in their children and that these reductions were sustained 1 year after the initiation of the mothers' treatment (

22). The children of mothers whose depression remitted early showed substantial decreases in externalizing symptoms and improved psychosocial functioning (

23). A report from a randomized trial of interpersonal psychotherapy also showed benefits to offspring depressive symptoms after their mothers were treated (

24). These studies suggest that a reduction in stress or in adverse early experiences associated with maternal remission may ameliorate symptoms in children who are psychiatrically vulnerable; however, these treatment studies do not have the ability to separate environmental and genetic impact.

There is accumulating evidence indicating that adverse childhood experiences have long-term consequences (

25). Epigenetic processes, such as DNA methylation, might mediate the effects of the environment during childhood on gene expression, which might then persist into adulthood and influence vulnerability to suicidal behaviors through effects on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activity (

26). Animal studies have shown that the quality of maternal parenting influences the development of individual differences in offspring behaviors and stress responses (

27,

28) possibly through epigenetic mechanisms (

29). A pilot intervention targeting parenting (e.g., monitoring, consistent discipline, and positive reinforcement) of maltreated preschool children immediately after their placement in a new foster home improved child functioning and altered HPA activity as assessed by salivary cortisol measures (

30). Given the strong relationships between parental and offspring psychiatric disorders, and the benefit of treatment and remission of maternal psychiatric illness on offspring psychiatric symptoms and disorders (

21–

24), maternal psychiatric illness is an important modifiable environmental factor.

The study of gene-environment interactions has been cited as one of the most important goals of genetic epidemiology (

31) and may further our understanding of how to prevent suicidal behaviors. The results of this study imply that biology is not destiny. We have identified a subgroup more likely to express vulnerability to suicide attempt hospitalization (i.e., those with BPSB who grow up in the context of maternal psychiatric hospitalizations), suggesting that facilitating the early identification and treatment of psychiatric disorders among mothers could be a critical step in the prevention of the generational transmission of suicidal behaviors.