Descriptions of a syndrome characterized by premenstrual psychological and physical distress have a long history, dating from the time of Hippocrates. At that time, a woman's monthly bleed was purported to “purge her bad humors.” Trotula of Salerno, an 11th-century female gynecologist, remarked in

The Diseases of Women, “There are young women who are relieved when the menses are called forth” (

1). In modern times, a cluster of premenstrual symptoms has been variably referred to as premenstrual tension syndrome (

2) or premenstrual syndrome (

3,

4).

In DSM, a moderate to severe form of premenstrual distress was classified according to the type, timing, and severity of symptoms. The initial diagnostic criteria for “late luteal phase dysphoric disorder” in Appendix A of DSM-III-R (

5) emphasized the timing and severity of symptoms by designating a minimum of five symptoms with predictable onset and offset in the late luteal and early follicular phases of the menstrual cycle, respectively. The DSM-IV work group on late luteal phase dysphoric disorder recommended the prospective use of standardized rating instruments to determine the true prevalence of the disorder in the general population of women, since previous studies suggested a prevalence ranging from 7% to 54%, depending on study methods and diagnostic algorithms (

6). The work group proposed that prospective daily ratings would improve the accuracy of diagnosis by confirming the timing of symptom onset and offset with respect to menstrual cycle phase and limit the inappropriate inclusion of women with milder symptoms or premenstrual worsening of ongoing affective disorders. For DSM-IV, late luteal phase dysphoric disorder was renamed “premenstrual dysphoric disorder” and the diagnostic criteria were modified slightly. However, the category remained in an appendix, as the work group believed additional research was needed to confirm the distinctiveness of the diagnosis from other disorders, its true prevalence, and its specific criteria.

All diagnoses and categories of mental disorders are undergoing scrutiny and potential revision in the process of developing DSM-5 (

7). The Mood Disorders Work Group for DSM-5 charged a panel of experts in women's mental health to 1) evaluate the previous criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, 2) assess whether there is sufficient empirical evidence to support its inclusion as a diagnostic category, and 3) comment on whether the previous diagnostic criteria are consistent with the additional data that have become available. The work group comprised eight individuals representative of various countries (United States, Canada, Sweden, United Kingdom), six of whom have specialty expertise in premenstrual dysphoric disorder or reproductive mood disorders. The literature was reviewed and thoroughly vetted by the panel, leading to the recommendation that premenstrual dysphoric disorder be moved from the appendix to reside as a diagnosis in the Mood Disorders section of the manual. In this review, we provide a summary of the literature and rationale behind this recommendation.

Before focusing specifically on the diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder, it is important to consider the general requirements for any disorder to be considered for inclusion in DSM-5. There must be sufficient empirical evidence that the disorder in question 1) is distinct from other disorders; 2) has antecedent validators, such as familial aggregation, presence in diverse populations, and environmental risk factors; 3) has concurrent validators, such as cognitive and temperament correlates, biological markers, and a certain comorbidity profile; and 4) has predictive validity with respect to diagnostic stability, predictability of course of illness, and response to treatment.

Addressing Requirements for Diagnostic Category

Evidence of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder as a Distinct Diagnosis

Epidemiological and clinical studies consistently show that some women experience a pattern of distressing symptoms beginning in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and terminating shortly after the onset of menses (

6–

17) (

Table 1). While the prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder varies depending on the population assessed and the study methods used, this pattern of symptom expression is distinct from that of other disorders in that the onset of symptoms occurs in the premenstrual phase (after midcycle) and has an on-off pattern that is recurrent and predictable (

18).

The DSM-IV criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder include symptoms most commonly endorsed by symptomatic women who have been surveyed in large clinical and community studies (

6,

9,

19,

20). While the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder overlap with those of other mood disorders, the cluster proposed for diagnosis is clearly different from those of other mood disorders. For example, the psychological symptoms most commonly reported by women with significant premenstrual distress are mood lability and irritability, not depressed mood or diminished interest and pleasure, as seen with major depressive disorder. Although mood lability and irritability are commonly observed in bipolar disorder, the pattern of predictable symptom onset and offset with phases of the menstrual cycle remains a key feature distinguishing premenstrual dysphoric disorder from other cyclic mood disorders. Finally, physical symptoms such as bloating and breast tenderness are both unique and among the most frequently reported premenstrual symptoms in women suffering from premenstrual dysphoric disorder (

20) (

Table 2).

With respect to familial risk for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, data from the Virginia Twin Registry (

21,

22), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Twin Register (

23,

24), and studies conducted in the United Kingdom (

25,

26) provide heritability estimates ranging from 30% to 80% for premenstrual symptoms. While each of these studies is based on retrospective reports of premenstrual symptoms, the Virginia Twin Registry study conducted two separate assessments, on average 72 months apart, in both members of 314 monozygotic and 181 dizygotic twin pairs. With a primary focus on psychological symptoms, the investigators found a remarkable stability of symptoms from the first to the second assessment. A best-fitting twin-measurement model estimated the heritability of the stable component of premenstrual symptoms at 56% and showed no impact of family environment factors (

22). A study examining the genetic and familial factors that affect the liability to major depression and to premenstrual symptoms found that 86% of the genetic variance and 88% of the environmental variance for premenstrual symptoms were not shared with major depression (

22). Likewise, other studies have found that a substantial portion of the genetic variance of premenstrual syndrome is not shared with major depression or with personality factors such as neuroticism (

21,

24).

Treatment approaches to premenstrual dysphoric disorder are shared with other mood disorders but are also distinct in several important ways. In women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, symptom response is better with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) than with noradrenergic agents (

27,

28). SRI treatment limited to the luteal phase appears to be as effective as daily administration (

29–

37), indicating a much shorter onset of action of these drugs when used for premenstrual dysphoric disorder than when used for depression and anxiety disorders. There is also evidence that certain ovulation-inhibiting hormonal treatments (

38,

39) and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (

40–

45) are efficacious in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and there is no reason to believe that these treatments would be effective in other mood disorders (

41). While GnRH agonist treatment appears to be effective for both the behavioral and physical symptoms of premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the majority of cases, hormone add-back is required to reduce the adverse sequelae of long-term hypogonadism. Unfortunately, such add-back (estradiol, progesterone, or both) leads to a return of negative mood in some patients (

46).

Antecedent Validators

As previously discussed, familial aggregation of premenstrual symptoms is due largely to genetic factors, with a very modest contribution, if any, from familial environment (

22,

25). In addition, premenstrual dysphoric disorder is not a culture-bound syndrome and has been found in epidemiological cohorts in the United States (

20), Canada (

16,

17), Europe (

8), India (

12), and Japan (

13). Rates are comparable in Caucasians and African Americans in the United States (

47), and symptoms appear to be relatively stable over time (

8,

22).

As in other psychiatric disorders, the possible relationship between environmental factors such as stress and the onset or expression of premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms, as well as psychological and physiological responses to stress, has been investigated (

48–

50). A history of interpersonal trauma (

51–

53) and seasonal changes have been suggested to have an impact on onset or expression of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (

54–

56), although confirmatory studies are required. Studies examining prior psychiatric history in women presenting with premenstrual dysphoric disorder demonstrate that major depression is the most frequently reported previous disorder (

57–

62). While this may be an accurate assessment, it is important to note that these frequency estimates are based primarily on clinical cohorts, which are more likely to have high rates of comorbidity. In addition, women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder may have been erroneously diagnosed with major depression, as the use of prospective ratings to confirm or rule out premenstrual dysphoric disorder would have been unlikely.

Concurrent Validators

Earlier work showed that women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder were hyperattentive to dysphoric stimuli. One study found that this negative attentional bias was limited to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (

63), while another found it expressed during both phases of the cycle (

64). Perception of the frequency and severity of stress has been reported to be greater during the luteal but not the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle in women with prospectively confirmed premenstrual dysphoric disorder compared with healthy comparison subjects (

65). Personality disorders are typically more common in individuals with axis I disorders, although this has not been clearly shown in women with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder when compared with the general population (

62,

65). One report shows a greater odds of avoidant personality disorder in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, but only among those age 30 or older (

66).

Similar to other psychiatric disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder is not clearly associated with particular biomarkers (

7). Nevertheless, the timing of onset and offset of symptoms with ovulation has led numerous investigators to examine the role of hormones in the pathogenesis of the disorder. Although studies of peripheral levels of ovarian and stress hormones, neurosteroids, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone have shown some positive findings, they have failed to consistently identify differences between women with and without premenstrual dysphoric disorder (

67–

79). Several, but not all, studies suggest that among women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, symptom severity is correlated with levels of estradiol, progesterone, or neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone and pregnenolone sulfate (

77–

79).

One of the most compelling findings supporting the role of ovarian hormones in the pathogenesis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder comes from a study by Schmidt et al. (

46) demonstrating that women with the disorder are more sensitive to both estradiol and progesterone than comparison subjects. In that study, women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder experienced significant improvement in core mood and physical symptoms with GnRH agonist treatment, only to have a return of negative affect when either estradiol or progesterone was reintroduced in a double-blind, placebo-controlled fashion. Notably, healthy comparison subjects pretreated with the GnRH agonist did not react negatively to administration of estradiol or progesterone.

Neuroimaging studies are in their infancy with regard to revealing the neural circuitry or neurochemistry of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. That said, functional MRI (

80), positron emission tomography (

81), and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (

67) demonstrate specific CNS differences in neural network activation, glucose metabolism, and neurotransmitter concentration, respectively, between prospectively characterized women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and healthy comparison subjects.

Finally, several lines of evidence indicate altered cortical activity or physiological arousal in women with well-characterized premenstrual dysphoric disorder relative to healthy comparison subjects (

82–

86). Using transcranial magnetic stimulation as a probe, Smith et al. (

84) showed that women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder do not experience a normal increase in neuronal inhibition in the motor cortex when progesterone and allopregnanolone levels are elevated (during the luteal phase). Two studies have utilized the acoustic startle procedure to probe physiological arousal over the menstrual cycle. Women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder did not differ from healthy comparison subjects during the follicular phase but had greatly accentuated baseline startle during the symptomatic luteal phase (

85). Using a slightly different paradigm, a second study (

86) showed that arousal was accentuated across the menstrual cycle in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder compared with healthy subjects, but particularly so in the luteal phase. In addition, the study found prepulse inhibition deficits in the luteal phase in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Together, these data are consistent with the assertion that abnormal CNS response to menstrual cycle-related hormone fluctuations contributes to the pathophysiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Another aspect of concurrent validity is the relationship between a specific disorder and other psychiatric illnesses. As mentioned previously, it is crucial that a set of criteria describe a disorder that is distinct from other disorders, although there may be phenomenological similarities, including patterns of comorbidity. The diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder requires that symptoms of mood or anxiety be limited to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, even though many women with ongoing psychiatric disorders report exacerbation of their primary illness during the days leading up to menstruation. In an early study of women with major depression and premenstrual worsening (

87), women who were treated with a tricyclic antidepressant improved in terms of depression but not premenstrual symptoms. These data are interesting in light of premenstrual dysphoric disorder's preferential response to SRIs (

28). Hartlage et al. (

88) found that in the community, many women with major depression show premenstrual worsening that is not often addressed therapeutically.

Predictive Validators

The research criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder have demonstrated diagnostic stability in several ways. First, to meet criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, women must experience the premenstrual pattern of symptoms in at least half of their menstrual cycles during the previous year. Although neither the criteria nor clinical practice requires women to prospectively chart their symptoms or cycles for 12 months, stability of symptom pattern from cycle to cycle has been documented in numerous studies using 2 to 3 months of prospective daily ratings (

22,

89). In addition to the pattern of symptoms with respect to onset and offset across the menstrual cycle, the type of symptoms experienced by a given patient remains consistent between cycles.

Finally, the DSM-IV work group on premenstrual dysphoric disorder reanalyzed a large data set (N=670) from women with premenstrual complaints who completed daily ratings as part of their participation in clinical trials for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder (

6) and confirmed that the symptom criteria included in DSM-IV reflect the symptoms most frequently reported to fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. Likewise, several members of the DSM-5 work group conducted a secondary analysis of epidemiological and clinical cohorts (

Table 2) whose members completed prospective daily ratings (

20). The community sample was an area probability sample from the Midwest, and the clinical sample comprised women who responded to advertisements for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder or premenstrual syndrome in Connecticut, New York, and Virginia. Each sample was roughly 65% white, 12%–15% Hispanic, 15%–17% black, and 5% other. Effect sizes were calculated according to the previous methods (

6), allowing for a measure of change in symptom severity between postmenstrual and premenstrual periods that considers background variability across the cycle. For each symptom, the postmenstrual follicular score (average ratings on days 7–12 postmenses) was subtracted from the perimenstrual score (average over the various 6-day intervals near menses) and divided by the standard deviation of each symptom rating over the entire cycle.

Table 2 highlights the symptoms that were similarly evaluated in the epidemiological and clinical samples. Peak symptom severity was greatest for physical symptoms in both cohorts. Peak severity for the most severe symptoms occurred either the day before or the day of onset of menstruation, although effect size calculations indicate that most symptoms were present 3 to 4 days prior to menstruation and continued through the first 2–3 days of menstruation. In addition, effect sizes revealed that physical symptoms such as bloating and low energy were common in both the general population and those seeking clinical care. Of the psychological symptoms, mood lability and irritability/anger ranked highest and were therefore listed first among the symptom clusters suggested for the DSM-5 criteria. In both cohort analyses, symptoms reflective of depressed mood or sadness demonstrated a lower effect size, further emphasizing the distinctiveness of premenstrual dysphoric disorder from major depressive disorder. Although the symptoms analyzed may be limited to those most queried with available daily rating scales, this body of research confirms the cluster of symptoms included in DSM-IV as well as diagnostic stability across time and among clinical and epidemiological cohorts with respect to types of symptoms endorsed.

Illness onset and trajectory of symptom severity should be relatively predictable over time for a given disorder. Treatment discontinuation studies show that women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have a resurgence of the same symptoms when medication is openly (

90,

91) or blindly (

92) discontinued. Long-term follow-up studies conducted on two relatively small cohorts found that 8–12 years after initial assessment, menstruating women continued to have premenstrual symptoms (

93,

94). For women in whom a diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder is established and who remain premenopausal, symptoms are likely to continue if they are not treated (

95). As anticipated, cessation of ovarian cyclicity with menopause, be it surgical, medical, or natural, brings an end to symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the majority of cases.

Finally, one of the most potent predictive validators of premenstrual dysphoric disorder as a disorder distinct from mood disorders is its preferential response to SRIs. A meta-analysis of the use of SRIs as treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder demonstrated uniformity of response (

96). Furthermore, in no other psychiatric disorder do SRIs reduce symptoms with as short an onset of action as in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Likewise, premenstrual dysphoric disorder is responsive to treatment with oral contraceptives containing the unique progestin drospirenone (

38,

39) as well as to ovarian suppression with GnRH agonists (

45,

46).

Benefits of Inclusion as a Category in DSM-5

It is with this information in mind that the DSM-5 panel of experts proposed the inclusion of premenstrual dysphoric disorder as a full category in this next edition of DSM. The benefit of moving premenstrual dysphoric disorder from the research criterion stage to that of full-fledged diagnosis is considerable from both a scientific and a clinical perspective. The research criteria for the disorder have already led to more rigorous characterization of women participating in randomized clinical trials and studies focusing on pathophysiology. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration and similar authorities in other countries have approved several pharmacological agents for the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder, making it a de facto diagnosis regardless of its position within DSM.

A category for premenstrual dysphoric disorder would describe individuals who are not well represented by other psychiatric diagnostic categories. Data from clinical as well as epidemiological cohorts show that many women experience symptoms that begin during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and terminate around the onset of menses. Prevalence rates vary considerably depending on study methods, particularly with respect to prospective or retrospective symptom reporting, consideration of symptom interference, and population sampling (

Table 1). In the two studies conducted using probability sampling of the general population and using prospective daily ratings for two complete menstrual cycles and confirmed premenstrual interference in functioning, the mean prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder was approximately 2% (

14,

15). The mean prevalence is higher (5%) if all studies of the prevalence of premenstrual dysphoric disorder are included (

Table 1).

A number of studies have found that women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder experience impaired functioning in various domains (

9,

97–

100) and that functional impairment improves during treatment (

99,

101). Such impairment among those affected argues for the need to detect and treat women who meet criteria for the disorder. Without clear diagnostic boundaries for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, symptoms may be dismissed and the diagnosis missed by providers. Clinicians may assume, for example, that the patient suffers from milder premenstrual syndrome or from an ongoing mood disorder such as major depression or dysthymic disorder. Because the treatments for these various conditions are distinct, accurate diagnosis is important. Moreover, the acceptance of strict diagnostic criteria may counteract unwarranted overdiagnosis of mild cases.

An additional reason for the suggested change is that it would promote accurate collection of data regarding the treatment need and delivery of services for premenstrual dysphoric disorder that could be obtained from epidemiological and treatment delivery studies. Such collection would thus benefit from premenstrual dysphoric disorder having a code of its own rather than being coded as depression not otherwise specified. Alternatively, it may today be coded as premenstrual tension syndrome according to ICD, which is also unfortunate given the lack of stringent criteria for this condition.

The inclusion of premenstrual dysphoric disorder as a diagnostic category may further facilitate the development of medications that are useful for treatment and may encourage additional biological research on the causes of the disorder. Finally, while the inclusion of criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the appendices of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV facilitated research, the work group felt that information on the diagnosis, treatment, and validators of the disorder has by now matured to the point that the disorder should qualify as a category in DSM-5. A move to the position of category, rather than a condition in need of further study, would provide greater legitimacy for the diagnosis (

102,

103).

The DSM-5 work group recognizes that some stakeholders may be concerned about the inclusion of premenstrual dysphoric disorder as a new diagnostic category. Some individuals and groups assert that a disorder that focuses on the perimenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle may “pathologize” normal reproductive functioning in women. Likewise, there may be concerns that since only women are at risk for the condition, they may be subject to inappropriate stigmatization and insinuation that they are not able to perform needed activities during the premenstrual phase of the cycle. Our group reviewed this literature and considered these points of view. However, because the prevalence statistics clearly indicate that premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a condition that occurs in a small minority of women, it would be inappropriate to generalize any premenstrual disability to women as a group. On the contrary, the inclusion of the diagnosis as a DSM-5 category, with its specific criteria and accompanying text, would emphasize that only a minority of women experience severe symptoms with accompanying distress and impairment. Analogously, while most individuals experience the feeling of sadness at some point in their lives, not all individuals have experienced a mood disorder. The overall health benefit for women of having an empirically based diagnosis would thus outweigh the potential for unfounded stigmatization or demeaning remarks that some groups fear.

Suggested Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

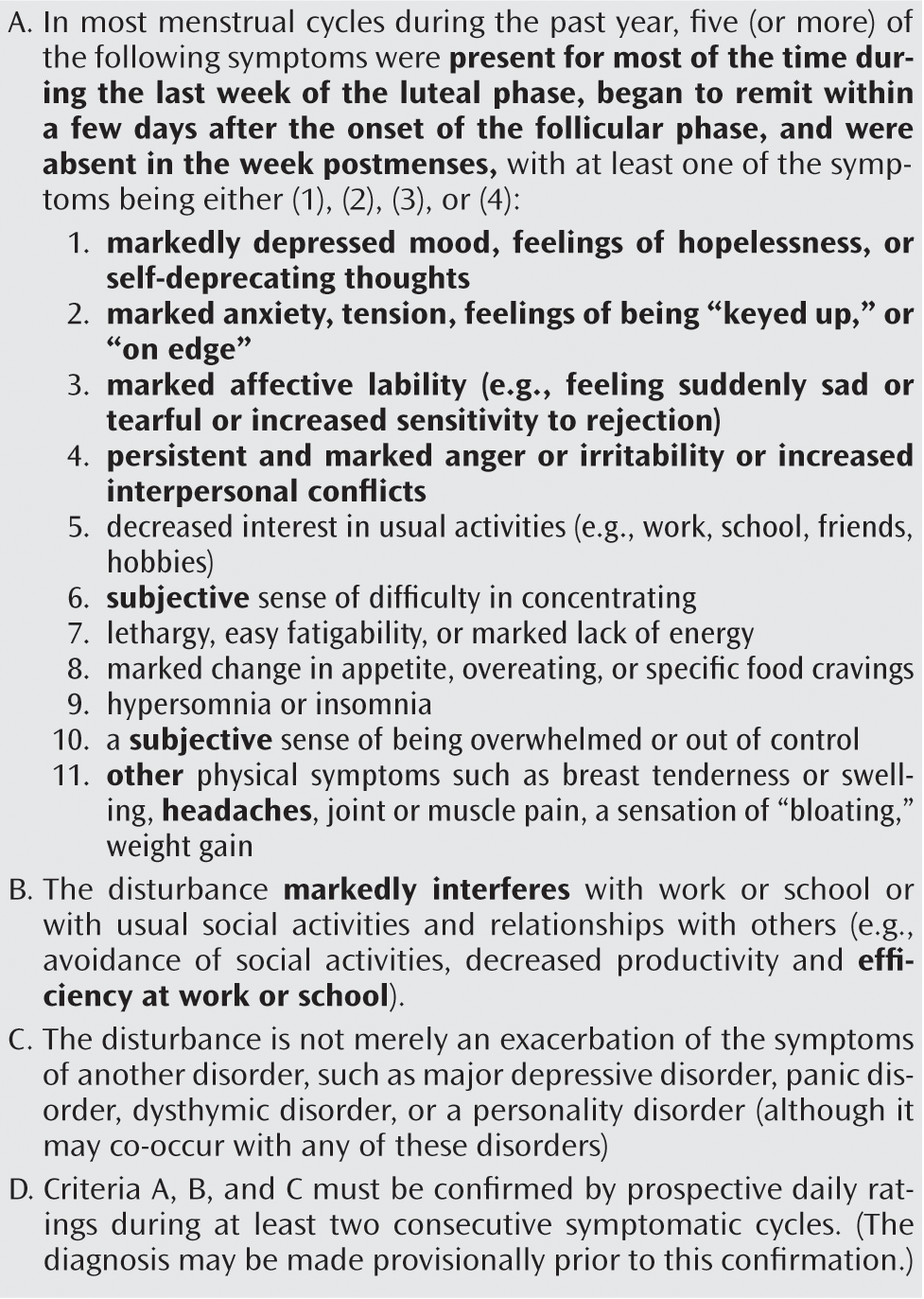

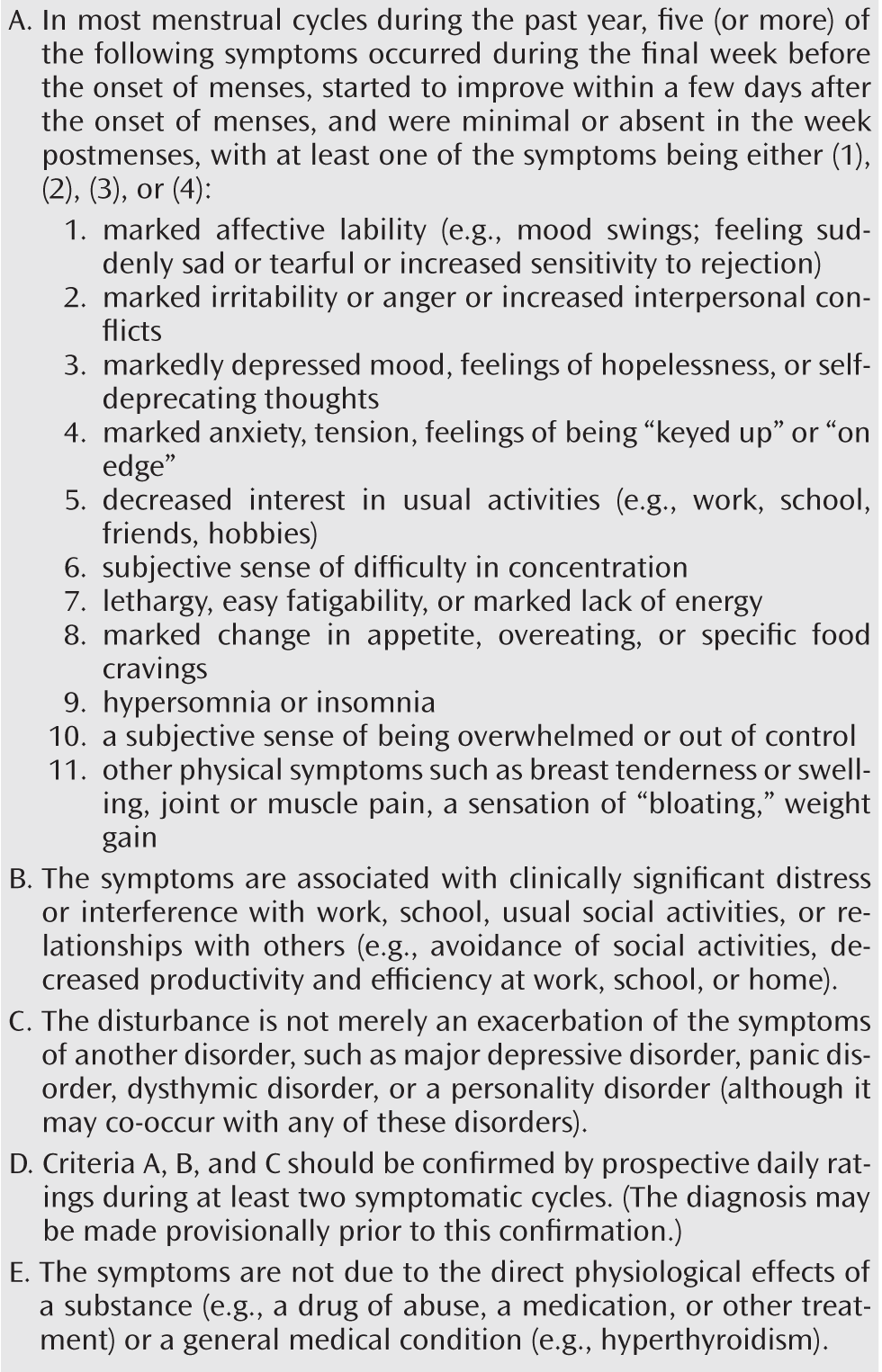

Figure 1 lists the criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder as worded in Appendix B of DSM-IV, and

Figure 2 lists the criteria recommended by the sub-work group to be used in DSM-5 as premenstrual dysphoric disorder becomes a full diagnostic category. The suggested changes are relatively minor and serve to refine the language of the DMS-IV research criteria. In criterion A, the wording on the timing of symptom onset and offset has been altered to be more explicit with respect to menstruation. A recent analysis of the prevalence of symptoms in the perimenstruum (

20) suggests that symptoms do not need to be present most of the week prior to menstruation, as indicated in the wording in DSM-IV, only present in the final week before onset of menses. Likewise, symptoms do not necessarily remit within a few days after onset of menstrual flow. They do, however, begin to

improve within a few days after onset of menstruation and are minimal, if not absent, in the week postmenses.

As previously mentioned, recent analyses of daily ratings from epidemiological and clinical samples strongly suggest that mood lability and irritability should be emphasized as the prominent psychological symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (

20). Hence, “marked affective lability” and “marked irritability or anger” have been moved to first and second in the symptom list. Criterion B now mentions “clinically significant distress” in addition to interference, as many highly symptomatic and distressed women muster coping skills to manage the impact of their symptoms on their work and interpersonal relationships. Also, criterion B now includes a reference to the impact of symptoms on productivity and efficiency at home and not just at work and school. Criterion C indicates that premenstrual dysphoric disorder may co-occur with, rather than be superimposed on, other disorders, maintaining the notion that women with other psychiatric disorders may also have premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The importance of prospective confirmation of the pattern and severity of symptoms with respect to functional impact has been retained in criterion D, although a provisional diagnosis may be made based on clinical history. Prospective daily ratings not only are helpful in confirming the diagnosis of premenstrual dysphoric disorder and ruling out premenstrual worsening of other conditions but also provide a baseline for comparison of the effectiveness of treatment interventions once they are initiated. While premenstrual exacerbation of depression and anxiety disorders is clinically relevant to this discussion, to date there are insufficient data to determine the prevalence of these conditions, and they must be excluded during the assessment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder, as there are distinct treatments for premenstrual dysphoric disorder that could worsen symptoms in women with premenstrual exacerbation of other disorders. Confirmation of criteria B and C is no longer considered necessary to the diagnosis, as distress or interference in functioning is typically ascertained during the psychiatric assessment. Finally, criterion E has been added to highlight the distinctiveness of premenstrual dysphoric disorder from an ongoing medical disorder or medication- or substance-induced conditions.

Conclusions

Current data support the criteria listed in Appendix B of DSM-IV for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Recent analysis of clinical and epidemiological samples has helped clarify the timing of peak symptom severity and the types of symptoms most frequently experienced by women with premenstrual complaints. It is clear that only a minority of premenopausal women—far less than 10%—will experience premenstrual distress of the type and severity that would meet the proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Thus, the normal menstrual fluctuations in physical and emotional symptoms experienced by the majority of women would not be considered pathological if premenstrual dysphoric disorder becomes a distinct category in the Mood Disorders section of DSM-5. The benefits of including premenstrual dysphoric disorder in DSM-5 will be substantial, as it will enhance not only research and clinical care but also the credibility of women who experience significant monthly distress.