Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (briefly called temper dysregulation disorder with dysphoria) has been proposed by the DSM-5 work groups for childhood and adolescent disorders and mood disorders to account for children with severe emotional and behavioral problems, of which a prominent feature is nonepisodic (or chronic) irritability (

1). Such a phenotype had been conceptualized as pediatric bipolar disorder (

1,

2), but evidence from both community and clinical longitudinal studies suggests that such irritability is associated with later unipolar, but not bipolar, mood disorders (

3–

5). The work groups adapted the “severe mood dysregulation” category proposed by Leibenluft et al. (

6) by opting for a more descriptive name and eliminating hyperarousal as a criterial symptom. Thus, the criteria for the proposed disorder include frequent (three or more times per week) severe temper outbursts combined with persistently negative mood between outbursts. These symptoms must be present for at least 12 months in multiple settings, have an onset before age 10, and the child must be at least 6 years old. The disorder has proven to be one of the more controversial proposals for DSM-5 (

7–

10).

Concerns related to this proposed diagnosis fall into two groups: 1) the potential negative consequences of adding a new childhood diagnostic category (e.g., the possibility that it might result in increased medication use in young children or a popular backlash against pathologizing “normal” behavior) and 2) the lack of any empirical basis for the definition (

7–

10). The justification for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder itself states, “It can certainly be argued that it is premature to suggest the addition of the disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis to DSM-5, since the work has been done predominately by one research group in a select research setting, and many questions remain unanswered” (

1). But this understates the problem. All research to date has focused on severe mood dysregulation, not the proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder criteria. As noted above, the latter omitted the hyperarousal criterion and also differ in terms of criteria related to the onset of symptoms (age 10 years for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and age 12 for severe mood dysregulation). There are in fact no published empirical studies that have focused on the newly proposed criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Our goal in this study was to review the relative utility of the proposed criteria in community samples of children and to determine whether the children who meet these criteria display a pattern of functioning indicative of psychopathology.

Discussion

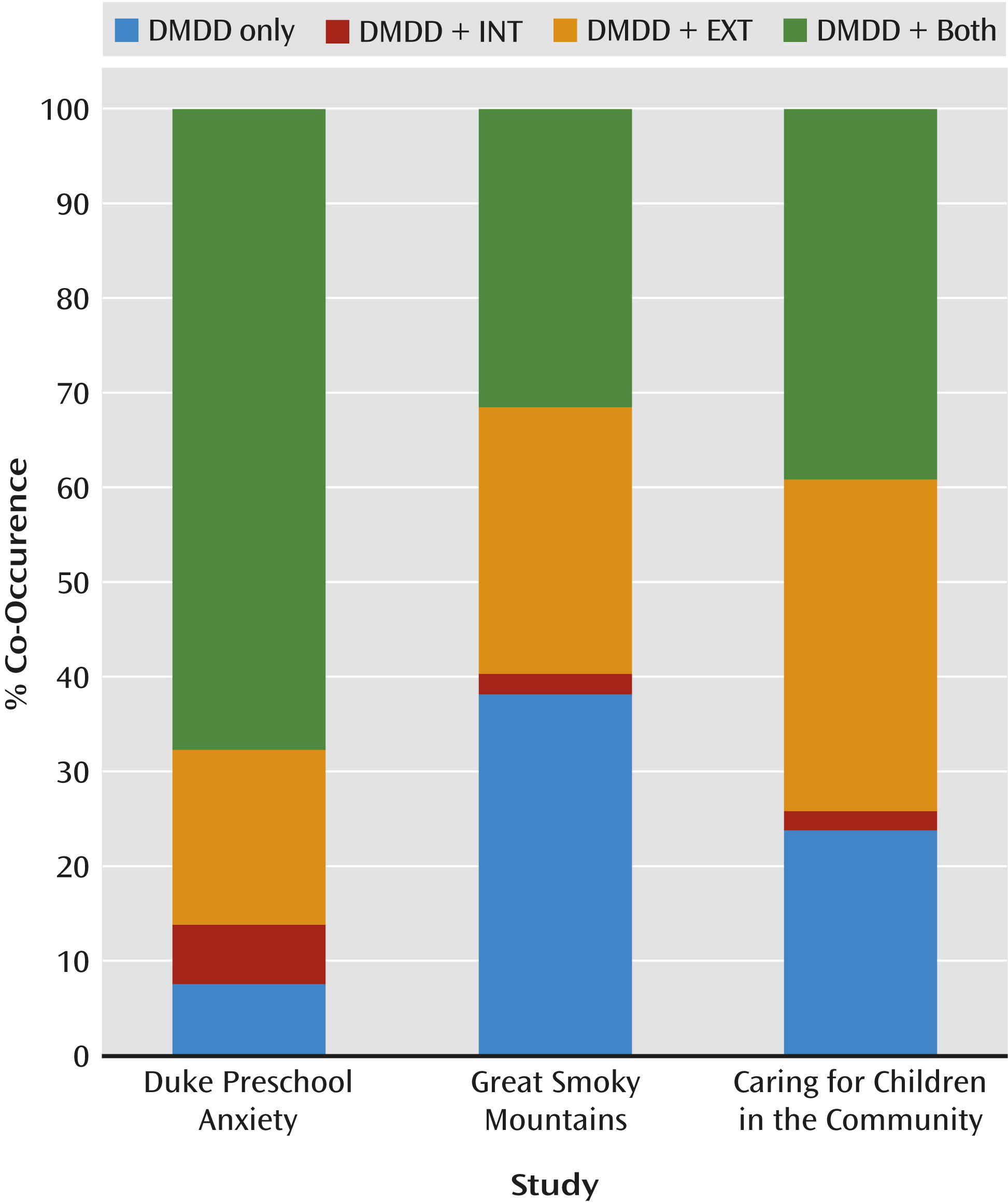

To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the proposed criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in community samples. The studies evaluated children and adolescents from 2 to 18 years old in rural and urban communities and included large groups of European Americans, African Americans, and American Indians. Disruptive mood dysregulation occurred at relatively low rates in the community, and it most often occurred in combination with other psychiatric disorders. This propensity toward comorbidity extended to all common psychiatric disorders but was strongest for oppositional defiant disorder and depressive disorders. Overall, disruptive mood dysregulation met the standards of psychiatric caseness tested: it was comorbid with psychiatric disorders and was associated with high levels of social impairment, school suspension, all types of service use, and family poverty. This does not clarify its distinctiveness from existing disorders, however.

A few limitations of this study should be kept in mind. First, the investigation of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in the three studies relied exclusively on psychiatric interviews designed to assess other disorders. Test-retest reliability data are not available for disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. None of the samples were collected to approximate a nationally representative sample of children, although all studies employed sampling and weighting strategies to minimize selection bias. Furthermore, results from these representative community samples will likely differ from clinical samples of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. All studies focused on a 3-month primary period to minimize recall bias and forgetting.

In these samples, disruptive mood dysregulation was relatively uncommon in childhood and adolescence. By comparison, 3-month rates were between 2% and 3% for depressive disorders and between 2% and 5% for conduct disorder in the older samples (

12,

13). These rates are consistent with the proposed justification for disruptive mood dysregulation as a “severe mood disorder” (

1). It was not the case, however, that the primary symptoms were uncommon. It was only when frequency, duration, and cross-context criteria were applied that a relatively uncommon phenotype was identified.

The prevalence of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in the preschool sample was 2–3 times that observed in the older samples. This is not surprising given the literature identifying early childhood as a peak period for temper tantrums and irritability (e.g., see Table 2 in Egger and Angold [

21]). Developmental differences are often used to justify amended criteria, and we present one example of alternative frequency thresholds for criteria B and C that could attenuate prevalence differences across development.

In the two older samples, application of the onset criterion had only a minimal effect on the prevalence rates. Furthermore, no justification was provided by the DSM-5 work groups for why this disorder cannot be diagnosed before age 6 (

1). This age criterion precludes the diagnosis for preschoolers, yet our results suggest that disruptive mood dysregulation disorder can be diagnosed in this population and that its comorbidity patterns were generally similar to those observed in older children. The DSM-5 Task Force states that “only by having consistent (reliable) diagnoses can researchers compare different treatments for similar patients, determine the risk factors and causes for specific disorders, and determine their incidence and prevalence rates” (

22). If this is so, then it might be preferable to eliminate this criterion to facilitate the study of severe irritability across development.

A primary concern has been whether the proposed criteria identify a distinct diagnostic entity (

8). Comorbidity is common in psychiatry. In a meta-analysis of childhood comorbidity patterns, median odds ratios for comorbidity ranged from 3.0 for ADHD with anxiety to 10.7 for ADHD with conduct disorder (

23), and comorbidity rates from individual studies were often much higher. Yet these high levels of pairwise associations are not typically considered a threat to the validity of the diagnostic system. The observed comorbidity rates in the present study were generally within the range observed for other disorder pairs with the exception of oppositional defiant disorder (odds ratios ranged from 52.9 to 103.0). It was also the case that disruptive mood dysregulation disorder did sometimes occur alone, particularly in the older samples.

The high levels of co-occurrence with oppositional defiant disorder, however, require further attention and belie proposed attempts to categorize disruptive mood dysregulation as a mood disorder only. We believe that a provisional effort should be made to clarify the nature of this overlap before the publication of DSM-5. At the same time, cross-sectional comorbidity is only one consideration, and evidence from longitudinal studies (including the Great Smoky Mountains Study) has linked severe mood dysregulation with later mood disorders (

3–

5). This is exactly the same pattern that has been found for the putative behavioral disorder of oppositional defiant disorder (

4,

24,

25), which so commonly co-occurs with disruptive mood dysregulation. Both oppositional defiant disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder should be considered to have mixed behavioral and emotional features.

This diagnosis does not identify an area of unmet need in the traditional sense of marking children with lower levels of service utilization. For childhood disorders, most studies have found that between 35% and 45% of those with a disorder have received treatment (

13,

26–

28). With disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, 3-month service use rates were between 45% and 61%. This does not mean, of course, that the treatment such children receive is either appropriate or even helpful. Concerns about inappropriate or untested interventions are no less a concern than the absence of treatment altogether.