Prolonged fatigue states—unexplained fatigue lasting more than 3 months—are among the most commonly reported forms of health-related morbidity. International studies of adults suggest that community prevalence rates of prolonged fatigue vary from 1.1% to 3.8% (

1–

4). The prevalence of prolonged fatigue in community samples of adolescents is highly variable, ranging from 0.7% to 7.4% (

5–

7), depending on the assessment methods and definitions used.

Although there are multiple common medical causes of fatigue (e.g., acute inflammatory conditions, anemia, thyroid deficiency, sleep apnea, end-organ failure, cancer therapy, chronic infection, and autoimmune disorders), a substantial proportion of chronic or prolonged fatigue remains unexplained. These states have primarily been studied in internal medicine and by relevant population health and research agencies, in response to the disabling symptom complexes presented by these individuals. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been at the forefront internationally of syndrome definitions and the enabling of specific research programs (

8).

Despite the long, rich, and cross-cultural history of primary chronic or prolonged fatigue, its classification has been a struggle in modern psychiatric classification systems, in part because of the causal attributions of its precursor, “neurasthenia,” by its early proponents (

9,

10) and its strong overlap with mood and anxiety states. Indeed, studies of community samples of adults reveal that 44%–75% of persons with prolonged fatigue report comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders (

1,

3,

4). Whereas ICD includes a category for neurasthenia, DSM does not recognize prolonged fatigue as a distinct entity (

1,

11). An important finding from analyses of international collaborative data sets from population-based studies, primary care, and secondary or specialist care settings is that a common symptom structure underlies prolonged fatigue states across cultures and health care settings (

12).

There are limited data on the prevalence and correlates of fatigue states and their association with mood and anxiety disorders in general population samples of adolescents. Because prolonged fatigue may be a feature of mood or other mental disorders (

13) and has a substantial impact on functioning and school attendance (

14–

17), quantifying the magnitude and correlates of prolonged fatigue in adolescents is of major public health importance. Recent data from a longitudinal twin study including 2,459 individuals ages 12–25 years indicate that fatigue states are common in both males and females, emerge in early adolescence (age 12 years), and are often comorbid with psychological distress (

18). With an increasing emphasis in clinical and neurobiological research on delineating underlying components of major mental disorders, there is an important gap in our knowledge about the age at onset and persistence of fatigue states and the developmental links with comorbid anxiety and mood disorders. This is particularly important in community-based samples.

The specific aims of the current study were to evaluate 1) the prevalence and reported age at onset of prolonged fatigue in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents, 2) the overlap of prolonged fatigue with depressive and anxiety disorders, and 3) the extent to which prolonged fatigue identifies a distinct subgroup of adolescents with specific correlates (sociodemographic variables, clinical characteristics, health indicators, service use) who are separate from adolescents with depressive and anxiety disorders only and from healthy adolescents.

Method

Sample

The National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (

19) is a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents ages 13 to 18 in the United States. Interviews were conducted between February 2001 and January 2004, and they used a modified version of the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3.0 (CIDI). The CIDI is a fully structured interview administered by trained lay interviewers to generate DSM-IV diagnoses, and it includes a section on fatigue (

20). A dual-frame sample was used, consisting of a household subsample (N=904) and a school subsample (N=9,217) (

21,

22). Recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the human subjects committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Measurement of Prolonged Fatigue

Prolonged fatigue was assessed in a separate CIDI module. Respondents were categorized as having prolonged fatigue if they met the ICD-10 criteria for neurasthenia: A) having experienced extreme tiredness, weakness, or exhaustion after minor physical or mental efforts (i.e., walking, shopping, reading, writing) lasting a few months or longer; B) having at least one of the following symptoms: feelings of muscular aches and pains, dizziness, tension headache, sleep disturbance, inability to relax, or irritability; C) not being able to recover from the symptoms mentioned in criterion A by resting or relaxing; and D) having these symptoms at least 3 months. Although the ICD-10 criteria for neurasthenia usually exclude persons with co-occurring mood disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, or panic disorder, we did not use these exclusion criteria, since a goal was to examine patterns of comorbidity of neurasthenia. Hence, the subgroup with comorbid disorders is most analogous to patients meeting current international definitions of more severe major mood disorders, which are characterized by both psychological distress and significant somatic symptoms. Therefore, the sample was categorized into four groups: 1) respondents with prolonged fatigue only, 2) those with prolonged fatigue plus a co-occurring depressive or anxiety disorder (i.e., major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or panic disorder), 3) those with only a depressive or anxiety disorder, and 4) those without any lifetime fatigue, depression, or anxiety. Note that respondents with depression or anxiety who lacked somatic symptoms may have had less severe forms of these disorders.

Measurement of Correlates

Sociodemographic variables recorded were gender, age, ethnicity, and education. Clinical characteristics included age at onset of prolonged fatigue, ages at earliest onset of depressive and anxiety disorders, and lifetime comorbidity with other DSM-IV psychiatric disorders assessed in the CIDI (social phobia, agoraphobia, specific phobia, and substance use disorder). In addition to these diagnoses, we determined the prevalence of mania and hypomania and the comorbidity of depressive disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder), and substance use (alcohol abuse or dependence or drug abuse or dependence) in selected groups. Severity of role impairment was assessed with the Sheehan Disability Scale (

23) and measured as the maximum score on four domains (home, school/work, family, social).

Several health indicators were also included. Presence of somatic disorders was based on chronic conditions assessed in the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (

24). Respondents were asked whether they had ever experienced each of the conditions in this checklist and, if so, whether they experienced them at any time in the past year. We included the following conditions: migraine and other headaches, arthritis, chronic back or neck problems, chronic pain, allergies (including hay fever), and asthma. Smoking was categorized as never, ever, and current smoking. Body mass index (BMI) z scores were calculated from self-reported weight and height according to the 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States and were categorized into underweight (<5th percentile), normal (5th to <85th percentile), overweight (85th to <95th percentile), and obese (95th or higher percentile). Further, weekend and weekday sleep duration and self-reported physical and mental health were assessed.

Service use was based on parent reports for a subset (N=6,483) of the participants; information was collected on treatment in the past year for emotional or behavioral problems. Variables were created to indicate whether a person had received any mental health care (outpatient mental health clinic, mental health professional, drug or alcohol clinic, admission to psychiatric hospital or other mental health facility), any health care (any mental health care, general medical care, or school medication [subset of school services]), and any care (any mental health care, general medical care, human services, complementary or alternative medicine, juvenile justice, or school services) during the past year.

Statistical Analyses

The prevalences in the four groups were calculated for the total sample as well as by sex, age group, and ethnicity. Correlates of the four groups were evaluated, and differences among the three groups of adolescents with disorders were evaluated by using chi-square tests and analyses of variance (ANOVAs). A proportional hazard model was used to test differences in median age at onset. This was done in SUDAAN 10 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.); all other analyses were done in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). All analyses corrected for the complex sampling design and were weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and poststratification.

Discussion

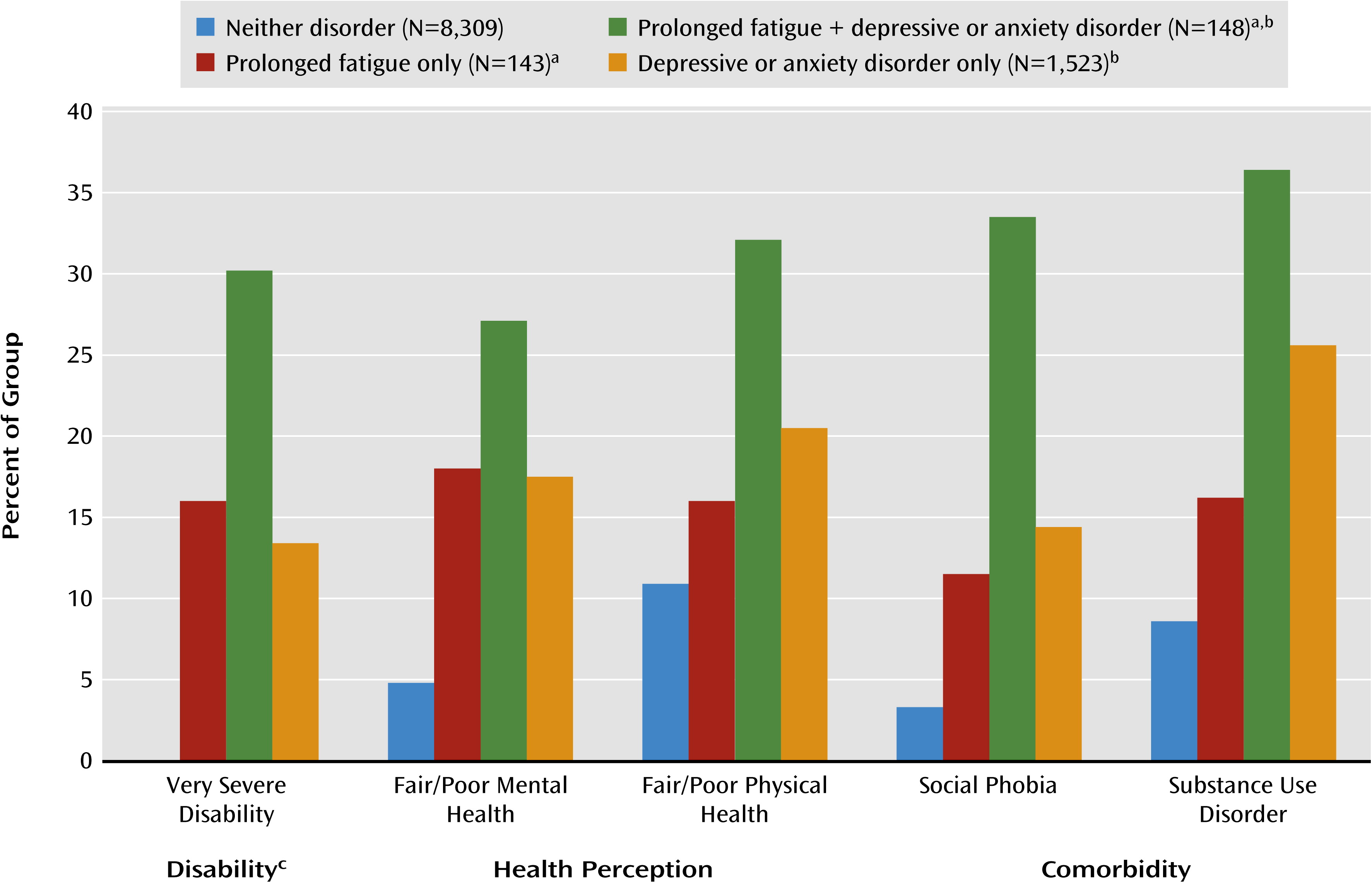

This study begins to address the current gap in knowledge regarding the magnitude, age at onset, and correlates of prolonged fatigue and other major mood disorders in the U.S. adolescent population. Similar to the few previous studies of adolescents (

5–

7), this study reveals that persistent and disabling fatigue states are common, affecting about 3% of the adolescent population. Consistent with cases in prior adult studies (

1,

3,

4), about one-half of the cases of prolonged fatigue are comorbid with anxiety or depressive disorders. However, youth with persistent fatigue without comorbid depression or anxiety also exhibited substantial impairment, suggesting that fatigue states are themselves an important clinical entity.

Adolescents with persistent fatigue without comorbid mood or anxiety disorders had a striking degree of disability, with about 60% reporting severe or very severe levels of disability across functional domains. It was also interesting that they lacked the common risk factors for poor health in adolescents, such as smoking and other substance use. Although depression is generally thought to be associated with higher BMI, the lower rate of obesity among those with fatigue plus depression or anxiety may indicate that fatigue could also characterize a distinct subgroup of adolescents with anxiety and depression. Similar to adolescents with depression or anxiety, those with prolonged fatigue had higher rates of pain-related conditions, including arthritis, back and neck pain, and headaches, than were found in adolescents without these disorders. This is consistent with the patterns of common somatic symptoms previously reported from a large sample of adolescent twins (

18) and the finding in that study that the genetic and environmental determinants of those symptoms were somewhat separate from those associated with anxiety and depression alone.

These results demonstrate that the presence of fatigue in adolescents with anxiety or depression results in a clinical presentation with more comorbidity and more severity or disability than anxiety or depression without fatigue. This suggests that the presence of fatigue may be used in clinical practice as an indicator of a more severe depressive or anxiety disorder. As predicted by the general hypothesis that adolescents who have comorbid fatigue and mood disorders are most likely to represent subjects with more severe depressive disorders (

25), we found that those with both conditions also had the highest rate of services use. Those with either prolonged fatigue only or anxiety/depression only used fewer services. While from the perspective of illness severity these differences may appear appropriate, they also highlight the extent to which young persons with disabling fatigue only or anxiety/depressive syndromes only do not receive care. If less severe forms are risk states for the onset of the more severe comorbid form, as would be predicted by other adolescent and adult studies of these overlapping phenotypes (

18), then the opportunity for secondary prevention of that later morbidity is not being addressed.

A variety of other developmental, longitudinal, and genetically informed studies of prolonged fatigue states have demonstrated that comorbidity with other mental disorders is common, particularly major mood disorders (

12,

18,

26–

30). Previous studies support the notion that mood disorders and fatigue states are intrinsically linked (presumably at the neurobiological level) and their comorbid state indicates a more severe disorder than either alone. However, there has been far less emphasis on investigating the age at onset of each of these conditions and the ways in which either state may represent an earlier phenotype of the same disorder or an independent risk factor for the development of either the comorbid or alternative condition. The prevalence of prolonged fatigue tends to be stable across adolescence, whereas mood and anxiety disorders tend to exhibit a large increase in prevalence with progression through the adolescent period (increasing from 11.1% to 19.2% from age 13 to 18). This suggests the role of other etiologic factors and is again consistent with the notion that somatic states such as prolonged fatigue may be due, at least in part, to genetic and environmental determinants that differ from those for common forms of anxiety and depression (

18,

29). For example, one specific environmental factor that may be directly associated with sleep problems in adolescents is the widespread use of electronic media (

31).

Although this study has several strengths, including the use of a large nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents, some limitations should be regarded when interpreting the results. First, the assessment of lifetime disorders is based on retrospective recall, which may be biased. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow us to evaluate temporal or longitudinal associations of fatigue and depression/anxiety phenotypes with great reliability; prospective studies are needed in this respect. Third, service use variables were based on questions about service use for emotional or behavioral symptoms but not for somatic complaints, and they were based on parent reports, which were available for only a subset of the sample. Fourth, the definition of prolonged fatigue was based on the ICD-10 definition of neurasthenia, which requires a duration of 3 months or longer, and this deviates from the traditional concept of fatigue, which requires a minimum of 6 months. Other differences include a lower number of somatic symptoms in our definition than is required for chronic fatigue syndrome, which requires multiple physical symptoms that include pain in multiple joints, sore throat, and tender lymph nodes. However, the recent International Consensus Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis—as chronic fatigue syndrome is often called—has discarded the duration criterion because “no other disease criteria require that diagnoses be withheld until after the patient has suffered with the affliction for six months” (

32). Accordingly, any significant fatigue state that causes considerable disability may warrant further medical and psychological assessment and, when present, certainly should be regarded as an indicator for severity when comorbid with depression or anxiety disorders.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that prolonged fatigue is a disabling condition in U.S. adolescents and is often accompanied by substantial psychiatric comorbidity. Comorbid fatigue states may indicate greater severity of depressive and anxiety disorders in adolescents, and even in the absence of comorbidity, the substantial disability and comorbidity with somatic conditions, particularly pain conditions, among those with fatigue states alone also suggest that prolonged fatigue is a clinically relevant entity. The high magnitude of comorbidity with physical disorders also highlights the importance of fatigue states as an index of somatic conditions. Although there were relatively high rates of mental health service use among adolescents with comorbid fatigue and mood/anxiety disorders, there was a striking paucity of service use among those with either condition alone, despite high levels of disability.