Schizophrenia affects ∼1% of the world’s population and is a highly debilitating disease (

1). It has been consistently associated with a life expectancy 10–25 years lower than that of the general population (

2). Efforts to reduce this disparity have been largely ineffectual, partly because the underlying etiologies and pathways remain unclear (

3–

6). Research from the past 20 years has shown that people with schizophrenia have an elevated mortality from cardiovascular disease and suicide (

6–

9). However, the relative importance of these risks, the effect of other comorbidities, and the underlying pathways remain unknown. Previous studies have had important limitations, including an overreliance on hospital or secondary care data, community-based samples, or insufficient sample sizes. No study has comprehensively examined the somatic health effects of schizophrenia using complete outpatient as well as inpatient data for a national population. The use of outpatient diagnoses would allow the inclusion of cases of schizophrenia and comorbidities less severe than those included in studies that are limited to hospitalized patients. This is important for avoiding the potential bias that may result from the sole use of hospital-based data, enabling more reliable risk estimates for comorbidities among schizophrenia patients and permitting examination of underdiagnosis of these comorbidities. Such information would advance our understanding of the causes of premature mortality among schizophrenia patients and help facilitate more effective strategies for improving the health of this vulnerable population.

We conducted a national cohort study of some 6 million Swedish adults to examine 1) the association between schizophrenia and somatic comorbidities, 2) the association between schizophrenia and all-cause and cause-specific mortality, and 3) the association between specific antipsychotic medications and mortality. Schizophrenia, comorbidities, mortality, and antipsychotics were ascertained using registry data obtained from all outpatient and inpatient health care settings nationwide.

Results

In this population of 6,097,834 Swedish adults, 3,490 women (0.11% of all women) and 4,787 men (0.16% of all men) were diagnosed with schizophrenia in any outpatient or inpatient setting in 2001 and 2002. Most schizophrenia patients were between 35 and 55 years old, and 57.8% were male. Only 8.1% were currently married or cohabiting, and 72.1% had never been married. They were disproportionately less educated (37.5% had completed only compulsory high school or less, compared with 20.8% in the general population), and only 7.1% were currently employed (

Table 1).

Comorbidities

Compared with the rest of the population, people with schizophrenia had more than twice as many outpatient clinic visits per year (mean=2.3, SD=5.5, median=1.4, compared with mean=1.1, SD=2.8, median=0.4; p<0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test) and hospital admissions per year (mean=1.0, SD=4.5, median=0.4, compared with mean=0.3, SD=2.5, median=0; p<0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test). The most commonly diagnosed specific chronic disease among schizophrenia patients was diabetes (12.5% of women and 11.0% of men during the 7-year follow-up period, compared with 5.1% and 6.4%, respectively, in the general population) (

Table 2). After adjusting for age and other sociodemographic variables, the risk of having a diagnosis of diabetes was 2.2 times greater (95% CI=2.05–2.48) among women with schizophrenia and 1.8 times greater (95% CI=1.70–2.02) among men with schizophrenia relative to other women or men. Schizophrenia patients also had more than a twofold greater risk of diagnosis with COPD and influenza or pneumonia (

Table 2).

In contrast, schizophrenia patients had no elevated risk of diagnoses of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, lipid disorders, cancer, or liver disease (

Table 2). After adjusting for age and other sociodemographic variables, men but not women had a modestly elevated risk of stroke diagnosis (men: adjusted hazard ratio=1.19, 95% CI=1.01–1.41). Some risk estimates were lower among schizophrenia patients, including a hypertension diagnosis among women (adjusted hazard ratio=0.74, 95% CI=0.66–0.84) and a cancer diagnosis among men (adjusted hazard ratio=0.84, 95% CI=0.73–0.96). Additional adjustment for substance use disorders resulted in smaller risk estimates for influenza/pneumonia, COPD, and liver disease and had modest or negligible effects on all other outcomes (

Table 2).

Mortality

In the entire study population, there were 634,276 deaths (10.4%) in 40.2 million person-years of follow-up. Crude mortality rates (per 1,000 person-years) were 32.5 and 27.7 for women and men with schizophrenia, respectively, compared with 15.7 and 15.3 for other women and men. Among women and men with schizophrenia, natural causes accounted for 90.9% and 82.3% of all deaths, respectively (compared with 96.5% and 94.1% in the general population), and suicide accounted for 3.5% and 7.6% of all deaths, respectively (compared with 0.6% and 1.6% in the general population) (

Table 3).

On average, women with schizophrenia died 12.0 years earlier than other women (mean age, 70.5 years, compared with 82.5 years), and men with schizophrenia died 15.0 years earlier than other men (mean age, 62.6 years, compared with 77.6 years). This life expectancy difference was not explained by unnatural deaths. Among all persons who died from natural causes, women with schizophrenia died 10.5 years earlier than other women (mean age, 72.1 years, compared with 82.6 years), and men with schizophrenia died 13.1 years earlier than other men (mean age, 65.1 years, compared with 78.2 years). Among all people who died from ischemic heart disease, women with schizophrenia died 12.7 years earlier than other women (mean age, 72.2 years, compared with 84.9 years), and men with schizophrenia died 14.5 years earlier than other men (mean age, 64.2 years, compared with 78.7 years).

After adjusting for age and other sociodemographic variables, schizophrenia was strongly associated with elevated all-cause mortality (women: adjusted hazard ratio=2.75, 95% CI=2.52–3.00; men: adjusted hazard ratio=2.44, 95% CI=2.25–2.64). Both women and men with schizophrenia had an elevated risk of death from ischemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes, influenza/pneumonia, COPD, and cancer (

Table 3). Among these causes, the largest hazard ratios were for influenza/pneumonia mortality in men and in women, COPD mortality in men, and diabetes mortality in women. However, the most common specific causes of death among schizophrenia patients were ischemic heart disease followed by cancer. Among specific cancers, both women and men with schizophrenia had more than a twofold greater risk of death from lung cancer (based on 41 deaths) relative to the rest of the population. Women with schizophrenia also had more than a twofold greater risk of death from breast cancer (based on 19 deaths) or colon cancer (based on nine deaths) (

Table 3). Further adjustment for substance use disorders resulted in modest attenuation of risk estimates for COPD mortality and had negligible effects for all other natural causes (

Table 3). Adjustment for other comorbidities in

Table 2 also had a negligible effect on any of the risk estimates (data not shown).

Among people who died from ischemic heart disease or cancer, schizophrenia patients were less likely than other people to have been diagnosed previously with these conditions (proportion diagnosed >30 days before death: ischemic heart disease, 26.3% compared with 43.7%, p<0.001; cancer, 73.9% compared with 82.3%, p=0.005). There were no sociodemographic differences between schizophrenia patients who were previously diagnosed with these conditions and those who were not. After restricting the analysis to people who were previously diagnosed, schizophrenia was only modestly associated with ischemic heart disease mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=1.36, 95% CI=1.05–1.77) and was no longer associated with cancer mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=1.04, 95% CI=0.87–1.24).

Among unnatural causes, schizophrenia was strongly associated with an elevated mortality from both suicide and accidents, and the relative risks were higher among women (

Table 3). After adjusting for age and sociodemographic variables, the risk of death from suicide was six times greater among women with schizophrenia and 4.4 times greater among men with schizophrenia relative to the rest of the population. Further adjustment for substance use disorders resulted in modest attenuation of these risk estimates, although they remained highly significant (

Table 3).

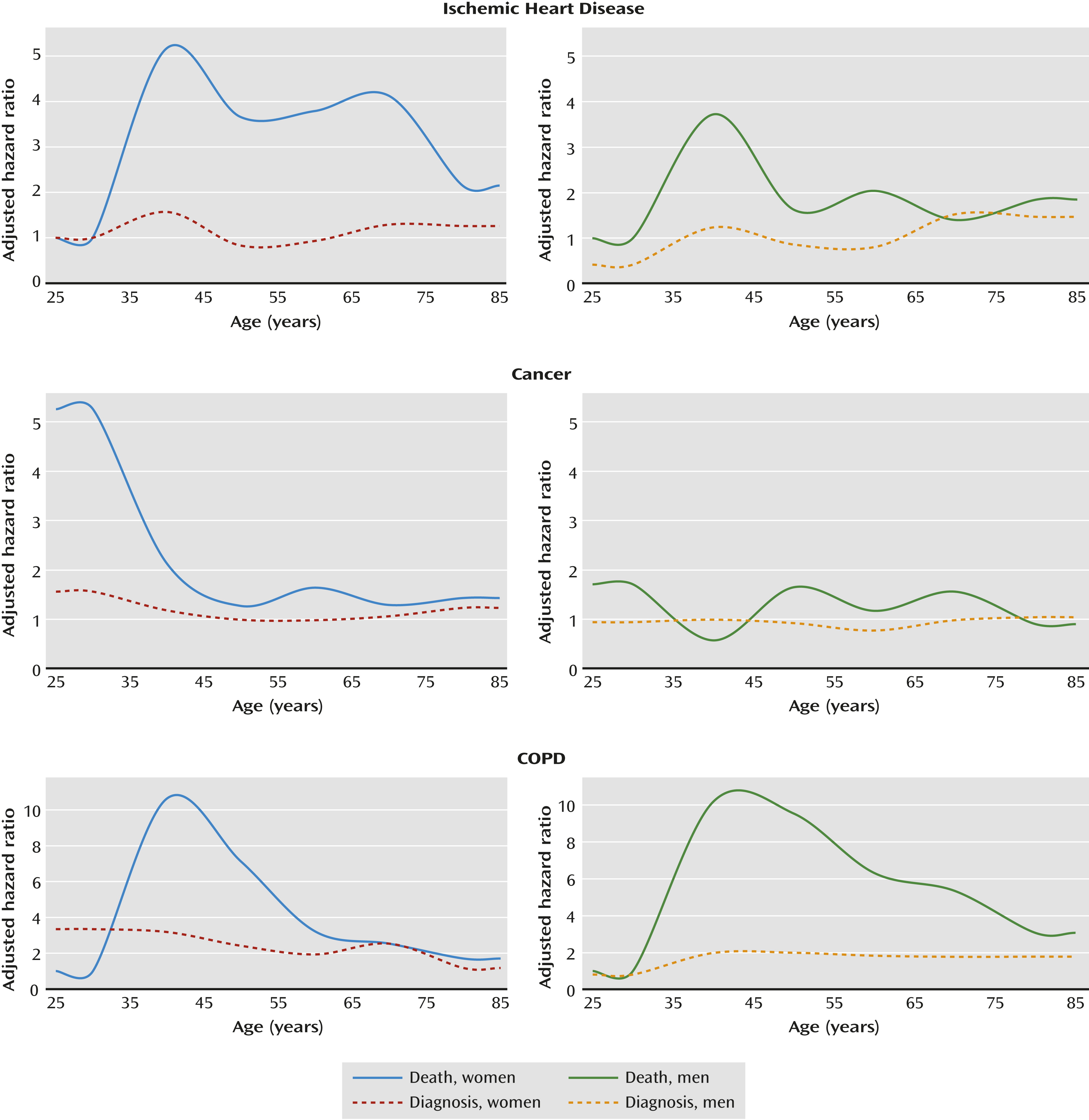

Figure 1 presents hazard ratios for the association between schizophrenia and selected outcomes relative to people without schizophrenia, stratified by age at study entry in 10-year categories and by sex, and adjusted for age and other sociodemographic variables. These graphs show the gap between risk estimates for cause-specific mortality and the corresponding risk estimates for a previous diagnosis with the same condition. The gap suggests that these conditions may be substantially underdiagnosed among people with schizophrenia across most ages, especially in young adulthood.

In analyses of potential interactions, the association between schizophrenia and all-cause mortality was stronger among women (pinteraction=0.005), currently employed individuals (pinteraction=0.007), and those without alcohol use disorder (pinteraction<0.001) or other substance use disorders (pinteraction<0.001). The association between schizophrenia and mortality was also slightly stronger among those age 65 years and older (pinteraction<0.001), although the stratified risk estimates did not have a consistent pattern across the full range of age categories. There were no significant interactions with marital status, education level, or income (for complete results, see Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article).

A sensitivity analysis to assess the potential mediating effect of smoking showed that adjustment for smoking, in addition to other substance use disorders, resulted in an attenuation of risk estimates of about 30% for lung cancer mortality and 10%–20% for mortality from ischemic heart disease, stroke, influenza/pneumonia, or COPD. However, all of these risk estimates remained significantly elevated, except for lung cancer mortality among women (fully adjusted standardized mortality ratio=1.54, 95% CI=0.97–2.45) (for complete results, see Table S2 in the online data supplement).

Antipsychotic Treatment

The association between specific antipsychotic medications and mortality was examined among persons who received any outpatient or inpatient diagnosis of schizophrenia between 2001 and 2009 (N=23,971), using “sole use of perphenazine” as the reference group (

Table 4). After adjusting for age, other sociodemographic variables, and substance use disorders, lack of antipsychotic treatment was associated with a greater all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=1.45, 95% CI=1.20–1.76), and specifically a greater mortality from cancer (adjusted hazard ratio=1.94, 95% CI=1.13–3.32) and a nonsignificantly greater mortality from suicide (adjusted hazard ratio=2.07, 95% CI=0.73–5.87) (not shown in the table). Other statistically significant findings included a lower all-cause mortality among users of aripiprazole or olanzapine. Conflicting results were obtained for quetiapine: “Any use” was associated with a lower all-cause mortality, whereas “sole use” was associated with a greater all-cause mortality (based on 28 deaths, including nine from cardiovascular disease and five from medication overdose) and a nonsignificantly greater mortality from suicide (adjusted hazard ratio=3.45, 95% CI=0.78–15.37; based on three confirmed suicides; not shown in the table). “Other antipsychotics” that were not prescribed in sufficient numbers for separate analysis were also associated with a modestly greater mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=1.19, 95% CI=1.00–1.43).

Discussion

In this large national cohort study, schizophrenia was strongly associated with an elevated mortality that was not accounted for by unnatural deaths. The leading causes were ischemic heart disease and cancer. Despite having more than twice as many contacts with the health care system than other people, schizophrenia patients had no increased risk of having a diagnosis of nonfatal ischemic heart disease or cancer but had a far greater mortality from these conditions, suggesting substantial underdiagnosis and/or undertreatment. Schizophrenia patients also had markedly greater risks of having diagnoses of diabetes, influenza/pneumonia, and COPD, and even greater risks of death from these conditions, as well as greater mortality from stroke, suicide, and accidents.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively examine the somatic health effects of schizophrenia using outpatient and inpatient diagnoses from all health care settings for a national population. Most previous studies have relied on hospital-based data (

4,

7,

25–

27), case-control data (

28), or community-based samples (

3). The availability of outpatient as well as inpatient diagnoses allows the inclusion of less severe cases of schizophrenia and comorbidities than studies limited to hospitalized cases, thereby avoiding potential bias and allowing the computation of more reliable risk estimates. It also enabled us to assess the extent to which important causes of mortality may be underdiagnosed in schizophrenia patients. Our findings suggest that the association between schizophrenia and ischemic heart disease or cancer mortality is largely related to underdetection rather than less effective treatment. Among people who died from ischemic heart disease or cancer, those with schizophrenia were significantly less likely than others to have been previously diagnosed with these conditions. However, among people who were previously diagnosed, those with schizophrenia had only a modestly greater mortality risk from ischemic heart disease and no increased cancer mortality risk compared with the rest of the population.

There are several potential reasons for underdetection of these conditions in schizophrenia patients. Some data have shown that schizophrenia patients are less likely to use general medical services than others with the same physical conditions (

29). In addition, those who do access the health care system at a similar or more frequent rate may be less likely to receive appropriate health care than the general population (

30,

31). Studies have reported that schizophrenia patients are less likely than others to receive coronary revascularization procedures (

32,

33), antihypertensive or lipid-lowering medication treatment (

34), standard diabetes care (

35), and cancer screening (

36). The large health risks we observed in schizophrenia patients highlight the need for more effective primary medical care tailored to this population and better adherence to standard clinical guidelines. Risk modification and screening for cardiovascular disease and cancer are particularly important given the elevated mortality from these conditions and the high prevalence of risk factors previously reported, including smoking, alcohol and other substance misuse, and poor nutrition and exercise (

21,

37). Smoking cessation programs have been shown to be effective for schizophrenia patients (

38) and need broader utilization to reduce the substantial health effects in this population.

Our overall mortality results are consistent with most previous estimates of a twofold to threefold greater mortality among persons with schizophrenia (

6). Our cause-specific results are consistent with most earlier findings for cardiovascular disease (

8), diabetes (

25,

28), COPD (

25,

28), pneumonia (

39), suicide (

6,

7), and accidents (

7,

26) while also clarifying other important causes. Previous investigations of cancer in schizophrenia patients have been inconsistent (

19,

40), with a recent meta-analysis reporting overall null results (

41). Our findings suggest that people with schizophrenia have an elevated mortality from cancer, particularly lung, breast, and colon cancer, and that this is at least partly related to underdetection. Schizophrenia patients also had an elevated mortality from stroke, consistent with previous reports of an elevated risk of stroke and/or poststroke mortality (

42,

43).

We found that the association between schizophrenia and all-cause mortality was stronger among women, the employed, and those without substance use disorders. Previous studies have reported inconsistent differences by sex, with a large meta-analysis reporting no overall difference (

6). The stronger association we found among the employed is consistent with a previous report of higher all-cause and suicide mortality among schizophrenia patients who were currently employed relative to those on disability pension (

44). Although this finding could be related to a better ability to cope with serious mental illness after retirement (

44), noncausal explanations are also possible. Unemployment, as well as alcohol and other substance use disorders, are strong independent risk factors for increased mortality, and hence schizophrenia may have a smaller proportional effect on mortality among people with these factors than among those without. Several studies have reported that the association between schizophrenia and mortality weakens with age (

4,

26,

45,

46), although this was not confirmed in our cohort. Additional studies with longitudinal sociodemographic and health data are needed to clarify potential modifying factors and the underlying mechanisms.

Lack of antipsychotic treatment was associated with a greater all-cause mortality in this cohort, as well as mortality from cancer and suicide. Second-generation antipsychotics have been hypothesized to increase mortality via metabolic pathways involving weight gain, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (

47,

48) or by cardiac toxicity (

49). The only evidence for such an effect in these data was limited to quetiapine, based on a small number of deaths. This was consistent with findings from a large study in Finland (

15), although we did not confirm that study’s finding of decreased mortality with clozapine, which was associated with a nonsignificant, modestly greater mortality in our study. Other commonly used antipsychotics were not associated with an elevated mortality.

The most important strength of this study was its ability to examine the association between schizophrenia and mortality or comorbidities with more complete ascertainment than was possible in most previous studies, using outpatient and inpatient diagnoses for a national population. This enabled us to make more robust and generalizable inferences by including patients with less severe schizophrenia and comorbidities treated in outpatient settings, avoiding bias that may result from the sole use of hospital-based data. It also enabled us to assess the extent of underdiagnosis of important causes of mortality in schizophrenia patients and to provide insights into appropriate interventions.

As in most previous large studies, individual data on smoking, exercise, or other direct lifestyle measurements were unavailable. We assessed the potential mediating effects of smoking using previously reported population smoking rates, and other substance use disorders using outpatient and inpatient diagnoses, but incomplete measurement of these factors may have resulted in underestimation of their effects. Misclassification of mild schizophrenia cases is possible, but is likely to be reduced compared with most previous studies because of the inclusion of outpatient data. A Swedish registry-based diagnosis of schizophrenia is also highly accurate, with a reported positive predictive value of 94% (

50). Finally, it is unclear to what extent our findings are generalizable to other health care systems. Underdetection of important causes of mortality in schizophrenia patients in Sweden, despite universal health care, raises the question of whether it may be an even larger problem in countries without universal health care.