Antipsychotics are widely used to treat symptoms of psychosis and disruptive behaviors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (

1). Although both conventional and atypical antipsychotics are used to treat patients with dementia, the use of atypical antipsychotics has significantly increased over the past 2 decades. These have similar efficacy and fewer side effects than conventional antipsychotics, especially in terms of sedation, extrapyramidal signs, orthostatic hypotension, and ECG abnormalities (

2,

3). Short-term trials have shown a mixed behavioral response to conventional and atypical antipsychotics in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (

4–

6).

There is significant concern among physicians and public health authorities about the reported increased mortality in elderly demented patients exposed to either conventional or atypical antipsychotics (

7–

10), although increased mortality is not a universal finding (

11–

13). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics found that these agents were associated with a small increase in risk for death in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (

8), leading the Food and Drug Administration to issue a black box warning (April 2005). In addition, studies in nonselected populations found an increase in heart disease and stroke among antipsychotic users (

14,

15), and a similar trend has been noted in placebo-controlled studies (

16). However, this result has not been found by others (

11,

17), and it has been hypothesized that previous exposure to antipsychotics or the presence of other comorbid conditions (e.g., metabolic syndrome) may have predisposed some patients to develop vascular events (

18).

We know very little about the effects of antipsychotics on the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease. The majority of trials with atypical antipsychotics have been conducted in institutionalized patients in the later stages of the disease and tended to be of short duration. Of the 15 trials examined by the Cochrane Review (

19), 13 used samples of institutionalized patients and two used samples of mixed dementia populations. Mean scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ranged from 2.8 to 14.4 (severe impairment), and the trials lasted only 10–12 weeks (

19). Only one study (

9) continued follow-up for more than a ear, and this was in a group of dementia patients residing in care facilities in the United Kingdom. That study found an increased risk for death in those treated mainly with conventional antipsychotics. However, only 13 of the 128 patients entered in the study completed the 48 months of follow-up.

The study of the long-term effects of antipsychotics in Alzheimer’s disease is extremely complex. The same symptoms (e.g., agitation and psychosis) for which antipsychotics are used can themselves accelerate the clinical progression of the dementia syndrome (i.e., confounding by indication) (

20–

23). In addition, these medications are used at different stages of dementia (including early), and in some cases they are used in combination with other psychotropic treatments (e.g., antidepressants). A study of patients with Alzheimer’s disease with moderate dementia taking mainly conventional antipsychotics (

22) found that psychosis, agitation, aggression, and antipsychotic use independently increased the risk of functional decline, and psychosis was associated with nursing home admission. Thus, while there may be a link between the use of antipsychotics and death in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the data supporting this conclusion are complicated by the fact that studies used samples of institutionalized patients who had severe cognitive deficits and exhibited symptoms that were themselves linked to cognitive or behavioral morbidity.

We report here an analysis of the long-term effects of antipsychotics in a large cohort of patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease who were followed between 1983 and 2005. This observation period is unique and fortuitous because it occurred during the time of transition from the use of conventional to atypical antipsychotics. This allowed us to examine the long-term effects of these two types of compounds on time to nursing home admission and time to death in the context of multiple clinical comorbidities.

Method

All of the patients were participants in the Alzheimer’s Research Program (1983–1988) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center of Pittsburgh (1985–2005). A total of 1,886 Alzheimer’s patients were enrolled between April 1983 and December 2005, of whom 1,587 had a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease (

24). The sensitivity for Alzheimer’s disease was 98% and the specificity was 88% in this cohort (

25). All patients received an extensive neuropsychiatric evaluation that included medical history and physical examination, neurological history and examination, semistructured psychiatric interview, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological assessment (

25). At the conclusion of these examinations, each individual set of results was reviewed by the study team (neurologists, neuropsychologists, and psychiatrists) at a consensus conference. Clinical evaluations were repeated on an annual basis. When patients stopped coming to the clinic, a telephone interview was conducted to obtain their clinical status, living arrangements, and medication use. The present study was conducted with 957 of the 1,587 patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease who had at least one annual follow-up evaluation. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with and without follow-up evaluations are presented in Tables S1 and S2 in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been published previously (

25). Briefly, we excluded patients with a lifetime history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder, a history of ECT, alcohol or drug abuse or dependence within 2 years of the onset of the cognitive symptoms, a history of cancer within the previous 5 years, or any significant disease or unstable medical condition that could affect the cognitive assessment (e.g., chronic renal failure, chronic hepatic disease, and severe pulmonary disease).

Psychiatric Examination

The psychiatric evaluations were conducted by academic geriatric psychiatrists using a semistructured interview (the Initial Evaluation Form) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Behavioral Rating Scale (

26). In addition, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (

27) was completed by the psychiatrist on the basis of interviews with each patient and primary caregiver. The Initial Evaluation Form has been used at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic of Pittsburgh since the early 1980s, and it was used to support the creation of diagnostic categories for DSM-IV (

28). For a diagnosis of major depression in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the Initial Evaluation Form has been validated relative to depressive symptoms identified with the CERAD Behavioral Rating Scale and the HAM-D (

29). The reliability of psychosis-related items of the CERAD Behavioral Rating Scale ranged from substantial to excellent agreement (kappa values, 0.60–0.85) among the psychiatrists (

30).

Each patient and caregiver was evaluated annually by psychiatrists, and any psychiatric diagnosis was made by consensus among Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center psychiatrists. In addition, a social worker interviewed the caregiver by telephone every 6 months between visits to determine the patient’s status and medication use; an annual contact was done for those who stopped coming to the clinic. Psychiatric symptoms were diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, and symptom contribution to the dementia syndrome was discussed among psychiatrists, neurologists, and neuropsychologists at the weekly consensus conference. For the present study, symptoms were recorded as either present or absent. If the initial presentation was ambiguous, symptoms were recorded as absent; that is, we used a high threshold for adjudicating a symptom as present. All patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for major depression (in remission, in partial remission, active, recurrent, or single episode) were classified as having depression. Agitation required the presence of signs of emotional distress, with or without increased motor activity. Aggression required the display of verbal or physical aggressive behavior. Delusions were defined according to DSM-IV criteria and were distinguished from confabulations, disorientation, and amnesia by requiring that the false beliefs persisted in spite of evidence of the contrary. Hallucinations were adjudged as present if the patient spontaneously reported a sensory perception with no concomitant external stimulus.

Neurological Examination

The neurological examination included a semistructured interview with the caregivers to assess the effects of cognitive loss on the most relevant instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., job performance) and performance in activities of daily living (e.g., hygiene and continence). The examination also assessed cranial nerve function, motor tone, abnormal movements, strength, deep tendon reflexes, release signs, plantar response and clonus, cerebellar testing, primary sensory testing (including graphesthesia and stereognosis), gait (including heel, toe, and tandem walking), and postural stability. The examiner also completed the New York University Scale for Parkinsonism (

31), the CERAD scale for extrapyramidal signs, the Hachinski Ischemic Scale (

32), and the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (

33). For extrapyramidal signs, the New York University scale was used from 1983 to 2003 and the CERAD scale from 2004 to 2005; extrapyramidal signs were considered present with scores of >4 on the New York University scale and >5 on the CERAD scale.

Statistical Analysis

We used two-factor analyses of variance (ANOVAs), t tests, and chi-square tests to analyze demographic and clinical characteristics of patients exposed or unexposed to antipsychotic medications. We used Cox regression models with time-varying covariates to determine whether there were differences in time to nursing home admission or time to death in Alzheimer’s patients with or without antipsychotic treatment. Cox models were also used to assess individually the effects of each psychiatric symptom and other psychiatric medications on these same outcomes. Because psychiatric symptoms and psychotropic medication use are more frequent as the disease progresses, the effects of individual symptoms and treatments were assessed as time-dependent covariates, which allowed us to examine the effect of medications and symptoms if they were present after baseline.

Three Cox regression models were used to determine whether exposure to antipsychotic medication was associated with time to nursing home admission or time to death. Model 1 included antipsychotic exposure, age, education level, gender, and MMSE scores. Model 2 included the items in model 1 with the addition of present baseline extrapyramidal signs, incident stroke/transient ischemic attack, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. Model 3 included the items in models 1 and 2 with the addition of aggression, agitation, psychosis, major depression, and dementia medication (e.g., cholinesterase inhibitors).

Results

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease who were exposed to antipsychotics had a longer duration of illness before the baseline clinic evaluation and longer follow-up time relative to those who had never taken antipsychotics. In addition, antipsychotic-exposed patients were younger; had less education; had worse scores on the MMSE, the Clinical Dementia Rating scale, and the HAM-D; had less hypertension; and were more likely to die or be admitted to a nursing home during follow-up than those who had never taken antipsychotics (

Table 1). Patients taking conventional antipsychotics had longer follow-up after the initial visit, were younger and less educated, had worse scores on the MMSE and the HAM-D, had better scores on the Hachinski Ischemic Scale, and were more likely to die or be admitted to a nursing home during follow-up than those treated with atypical antipsychotics or those who had never taken antipsychotics.

We found higher rates of psychosis, aggression, agitation, and antidepressant use and a lower rate of dementia medication use among those who used antipsychotics (

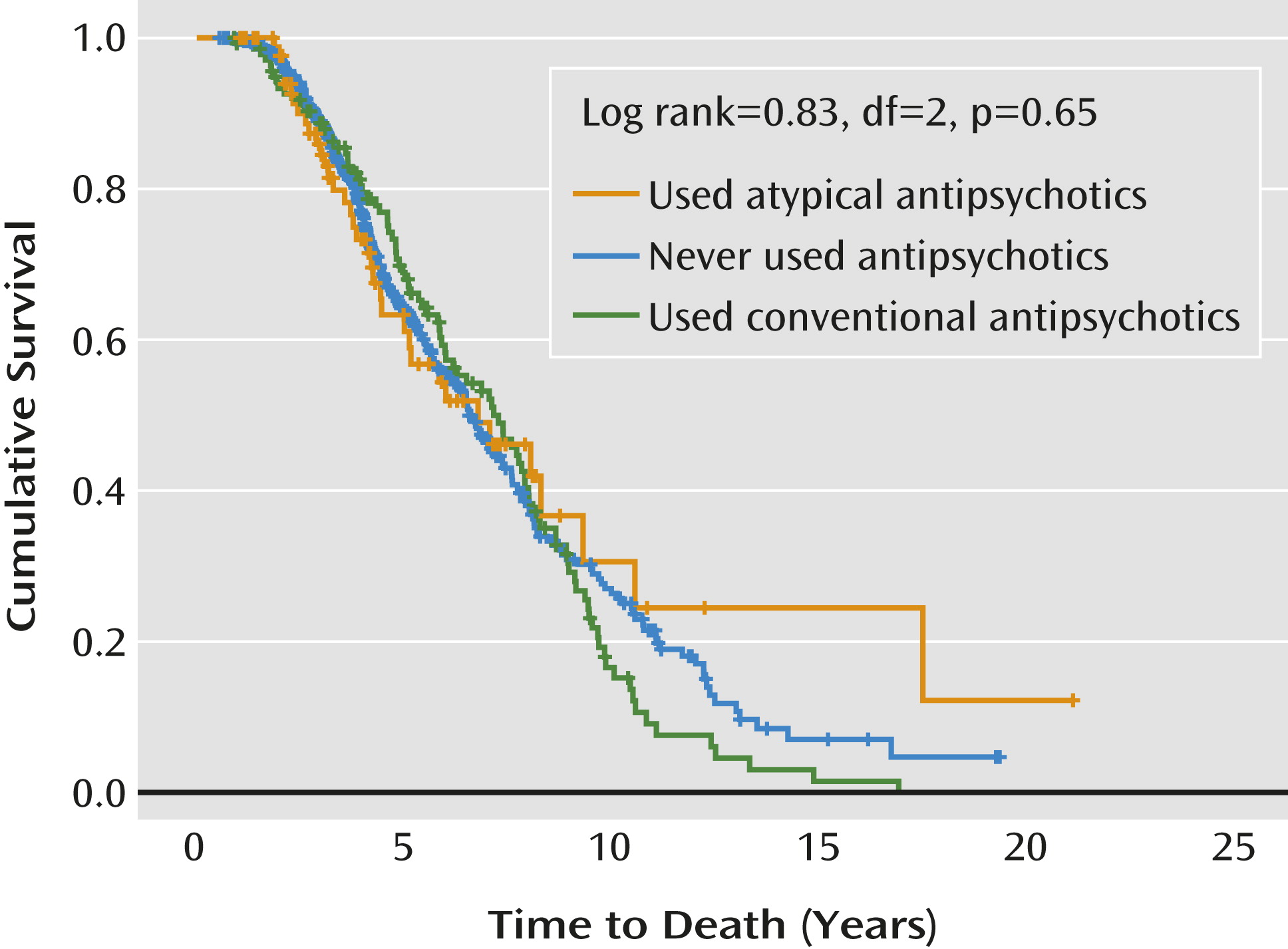

Table 2). Patients who had been treated with conventional and atypical antipsychotics had more psychosis and aggression than those who had never taken antipsychotics, and more patients with agitation had taken atypical than conventional antipsychotics. Patients exposed to atypical antipsychotics had more extrapyramidal signs compared with those taking conventional antipsychotics. More patients were taking antidepressants and dementia medication with atypical than with conventional antipsychotics. For informational purposes, a Kaplan-Meier plot depicts the time to death in patients with and without antipsychotic treatment at any time during follow-up (

Figure 1).

As a group, patients exposed to antipsychotics had a greater risk of going to a nursing home in models 1 and 2 but not in model 3 (see Table S3 in the online

data supplement). The risk of death was not increased in patients exposed to antipsychotics (see Table S4 in the online

data supplement).

Table 3 shows that patients taking conventional antipsychotics had an increased risk of nursing home admission in models 1 and 2 but not in model 3.

Education level, lower MMSE scores, extrapyramidal signs, heart disease, agitation, and psychosis were associated with nursing home admission. Neither conventional nor atypical antipsychotic use increased the risk of death (

Table 4), but age, education level, male gender, MMSE scores, extrapyramidal signs, and psychosis were associated with risk of death.

Discussion

This large longitudinal observational study revealed that a higher proportion of patients exposed to antipsychotic medications, especially conventional antipsychotics, were admitted to a nursing home or died compared with those who never took these medications. However, in time-dependent statistical models, these associations were no longer present after we adjusted for the symptoms for which the antipsychotic treatments were usually used (hazard ratio=2.2 compared with 1.3). This suggests that the primary correlate of negative outcomes was the psychiatric symptomatology and not the drugs used to treat these symptoms.

This observational study does not support the association between mortality and antipsychotic use that has been reported in institutionalized elderly patients (

34). The discrepancy may be a result of the fact that nursing home patients are more clinically heterogeneous and tend to be more cognitively and physically impaired than individuals commonly seen in outpatient clinics. Furthermore, interactions among multiple factors (including psychiatric symptoms) that have yet to be identified may be associated with antipsychotic-associated death in nursing home patients. For example, in a study conducted in Finnish institutionalized patients with dementia, while neither conventional nor atypical antipsychotics were associated with death, the use of restraints doubled the risk of mortality (

13).

Similarly, outcome studies from large databases should be interpreted with caution, as they include not only institutionalized and noninstitutionalized patients, but also patients with a lifetime history of psychiatric disorders and exposure to antipsychotics or with neurodegenerative processes that are themselves associated with increased mortality (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) (

35,

36). This may explain the lack of association found in some studies conducted in elderly individuals that did not include these types of patients (

11,

13). In addition, it seems that the highest reported risk of death occurs with conventional antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol) and with some atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone), but not with others (e.g., quetiapine) (

34,

37). Although our study had enough participants to examine the effects of antipsychotics on mortality and nursing home admission, we lacked statistical power to compare the effects among individual antipsychotic agents.

The results of this study suggest that it is the symptoms and not the medications that predict nursing home admission and death. The study of long-term effects of antipsychotics in patients with Alzheimer’s disease has strengths and limitations. It is difficult in observational studies to determine the duration of exposure to these medications as well as dosages. In addition, brief exposure to medications may be missed, especially if these occur between clinic visits or in the late stages of the disease. Thus, in the present study, if medication initiation and death occurred in the last 6 months between contacts, we may not have detected the use of antipsychotics. While studies based on claims data provide better information about dosages and date of therapy onset, they do not have information about whether the medication was actually used or about previous exposure to antipsychotics (

34). Similarly, while randomized controlled trials provide useful short-term information, they would have to last many years in order to capture time to nursing home admission or death. Furthermore, if a patient in a placebo group had increasingly severe symptoms, he or she would have to be placed on medication (i.e., breaking the blind) and then continued in long-term observation. If the medications are effective at treating the symptoms (in the medicated group), any decision to stop the medication incurs the risk that the symptoms will immediately return in some patients, who may then require long-term maintenance therapy. Indeed, in a recent study of risperidone treatment for patients with Alzheimer’s disease with psychosis and agitation, symptom relapse occurred when the antipsychotic was discontinued in a randomly assigned, double-blind fashion (

38).

Psychosis was a significant predictor of death, even after adjustment for antipsychotic use. This finding is consistent with a previous observation of a faster cognitive decline (

21) and increased mortality (

23) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease with psychotic features. This suggests that these patients live with a more aggressive Alzheimer’s disease phenotype, but the study of psychiatric symptoms and mortality in Alzheimer’s disease is complex. The psychotic phenomenon in Alzheimer’s patients does not occur in isolation and tends to develop in a constellation of symptoms that include agitation, aggression, sundowning, and inappropriate behavior across the spectrum of disease severity (

29). Thus, the psychotic symptoms may co-occur with other disturbing behavioral symptoms that can lead to death (

39). For example, agitation and aggression can lead to falls, which can cause head trauma or fractures, in turn leading to physical immobilization and subsequent increased risk of death. Aggression was also a risk factor for death when we examined the relationship between antipsychotic exposure and mortality (hazard ratio=1.30 (95% CI=1.01–1.67; see Table S4 in the online

data supplement).

Extrapyramidal signs were an independent predictor of nursing home admission and death, consistent with previous studies (

40,

41). Notably, extrapyramidal signs are frequent in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and practically all will develop an extrapyramidal sign during the course of the disease (

41). The presence of extrapyramidal signs can predispose patients to reduce their mobility, consequently increasing the risk of infections (e.g., pneumonia). The increased need for personal care in patients with extrapyramidal signs may also lead to nursing home admission. In this study, extrapyramidal signs were more frequent in patients taking conventional than atypical antipsychotics, but we did not examine the effect of the severity of the extrapyramidal signs (as distinct from their presence or absence) on mortality.

The study of factors related to mortality in patients with Alzheimer’s disease is complex, with multiple factors converging to increase the risks of nursing home admission and death. In this outpatient-based population with mild to moderate dementia, exposure to antipsychotics was not associated with an increased risk of nursing home admission after the presence of disruptive behaviors was taken into account. Rather, it was the psychotic/agitated phenotype that emerged as a critical factor influencing the natural and treated history of Alzheimer’s disease.