We conducted three sets of analyses that sought to clarify the etiological role of familial and community factors in drug abuse. All analyses used Swedish national samples, including twin and sibling pairs, and objective methods of drug abuse diagnosis using medical, legal, and pharmacy records.

Twin Sibling Models

Our twin sibling modeling results addressed four questions. First, despite substantial differences in methodology, the estimates for the heritability of drug abuse in this sample were within the range found in the previous twin studies, where heritability estimates for drug abuse or drug dependence varied from 31% to 74% (

4,

5,

7,

14). The largest of these studies (

14) produced a heritability estimate for abuse or dependence of 63%, midway between our estimates in males and females. Using ascertainment methods that did not depend on subject cooperation or on accurate long-term recall of socially undesirable behaviors, we provided an important confirmation of the results of previous twin studies that genetic factors contribute substantially to risk for drug abuse.

Second, most of the earlier twin studies (

4,

5,

7,

8) and our recent adoption (

9) and sibling studies (

10) found familial-environmental influences on drug abuse. We found robust evidence for shared environmental effects in males. One small twin study of drug abuse explicitly examined this question and found larger estimates for shared environmental effects (c

2) in males than in females (9% and 4%) (

5). Interestingly, when examining the most common substance of abuse, cannabis, their results were similar to those reported here, with a c

2 estimate of 24% in males and zero in females (

5). Our results are also consistent with evidence of shared environmental effects on alcohol abuse in Swedish males (

15). While the pattern of correlations suggested modest shared environmental effects in females, this effect was not detectable in twin modeling, perhaps because of the lower power resulting from the rarity of drug abuse in females.

Third, we had hoped to clarify sex differences in the patterns of risk factors for drug abuse. We found robust evidence for quantitative differences—genetic factors were considerably more important in the etiology of drug abuse in females than in males. We did not, however, find qualitative sex effects, but the presence of large shared environmental effects in only one sex makes the detection of qualitative sex effects much more difficult, because both effects predict lowered correlations in opposite-sex compared with same-sex dizygotic and sibling pairs.

Fourth, because we could study sibling pairs as well as twins, we could evaluate whether, for environmental reasons, dizygotic twins resembled one another more for their risk for drug abuse than did full siblings. Looking at the raw correlations (

Table 1), we saw such a trend in both male-male and female-female pairs. In model fitting, however, we detected evidence for a special twin environment only in males. This is also likely a result of the lower power of our analyses in females. However, the impact of the special twin environment in males (3% of variance) was much smaller than that seen for shared environmental effects (23%). This result suggests that experiences unique to twin siblings had a less important impact on resemblance for drug abuse than the general background family, school, and community environment shared by all siblings. Furthermore, expanding beyond twins to include a large sample of sibling pairs in our modeling renders our findings more generalizable, as siblings are among the most common of human relationships.

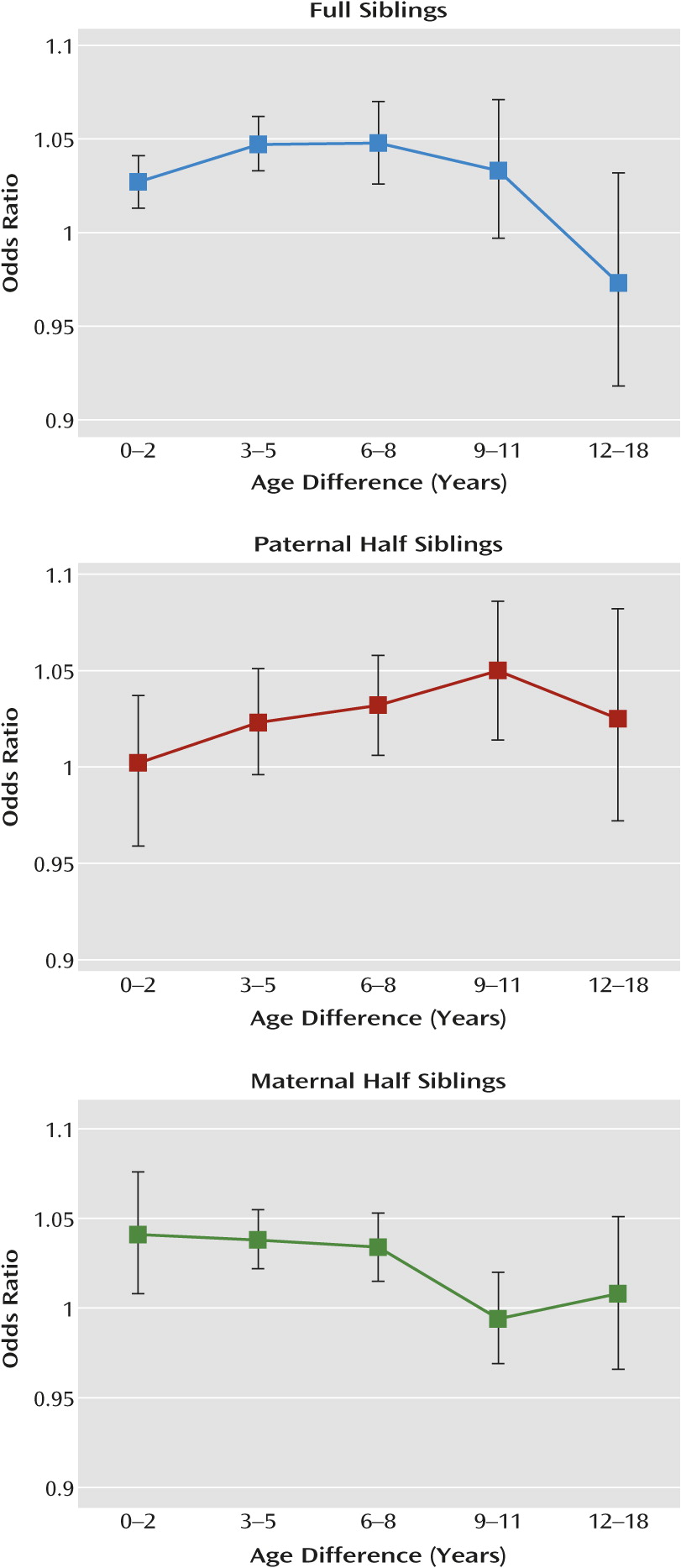

In a previous analysis of resemblance for drug abuse in Swedish siblings (

10), we reported that resemblance was significantly related to age difference. Those born within 2 years of one another were consistently more similar with respect to risk for drug abuse than those born more than 5 years apart. Our present findings of greater resemblance for drug abuse in dizygotic twins than nontwin siblings are consistent with this finding, as dizygotic twins are essentially siblings born at the same time.

In our Swedish studies of drug abuse, we are in the relatively unique position of being able to directly compare our findings from twins and siblings to those from an adoption study using identical diagnostic procedures in the same population (

9). Heritability estimates can be obtained from our adoption findings by doubling the tetrachoric correlation for drug abuse between the adoptee and their biological parent or full sibling. These estimates agree closely with one another (34% and 29%, respectively) and are considerably lower than those estimated from our twin sample. One way to estimate shared familial environment from adoption data is to estimate the correlation in risk between the adoptee and their adoptive siblings. This equaled 0.19, close to our estimate of shared environmental effects in males.

Lower heritability estimates from adoption studies compared with twin samples has been seen for other phenotypes (

16–

18) and might have several causes. The degree to which this discrepancy reflects chance factors (our twin sibling sample was much larger than our adoption sample), upward biases on our estimation of heritability from the twin sample or downward biases on our estimation of heritability from our adoption sample, will require further investigation.

Impact of Years of Residence in the Same Household or Community

Our second set of analyses used the detailed information available in Swedish registries to clarify the nature of shared environmental influences on drug abuse. A critical feature of our design was to hold the degree of genetic resemblance constant and then examine whether years of residence in the same household, small residential area, or metropolitan area predicted resemblance for drug abuse in sibling pairs. In so doing, we isolated the impact of the environment that, in typical family studies, is confounded with genetic effects. We performed these analyses in three sibling groups, treating them as replicate experiments.

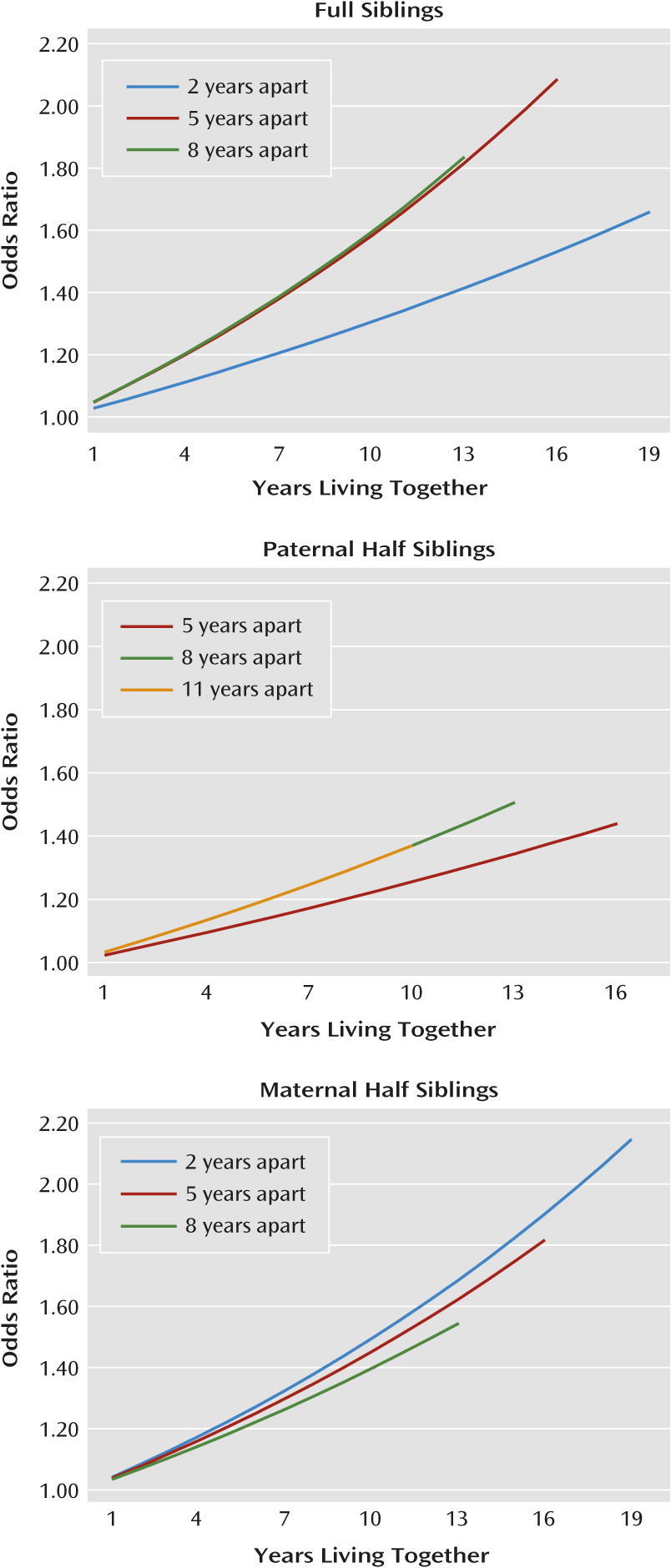

Five findings from these analyses are noteworthy. First, confirming results from our twin sibling modeling, in male-male full siblings, the number of years of living together in the same home was systematically related to resemblance for drug abuse. For each year of living in the same household, the probability that sibling pairs with at least one member affected with drug abuse would be concordant typically increased between 2% and 5%. Extrapolated over the expected years of cohabitation, this produced odds ratios ranging from 1.6–2.0. When compared with the total odds ratios for drug abuse among full siblings (∼5.0–8.5), cohabitation accounts for a modest component of resemblance, consistent with estimates from our twin sibling models.

Second, the impact of cohabitation effects was similar in the three sibling groups. If our measures were confounded with genetic effects, they should have been much stronger in full siblings than in half siblings.

Third, the effect of cohabitation on resemblance for drug abuse was less potent in sibling pairs of very different ages. Across our three sibling groups, cohabitation effects were small and nonsignificant for pairs with more than 12 years difference in age.

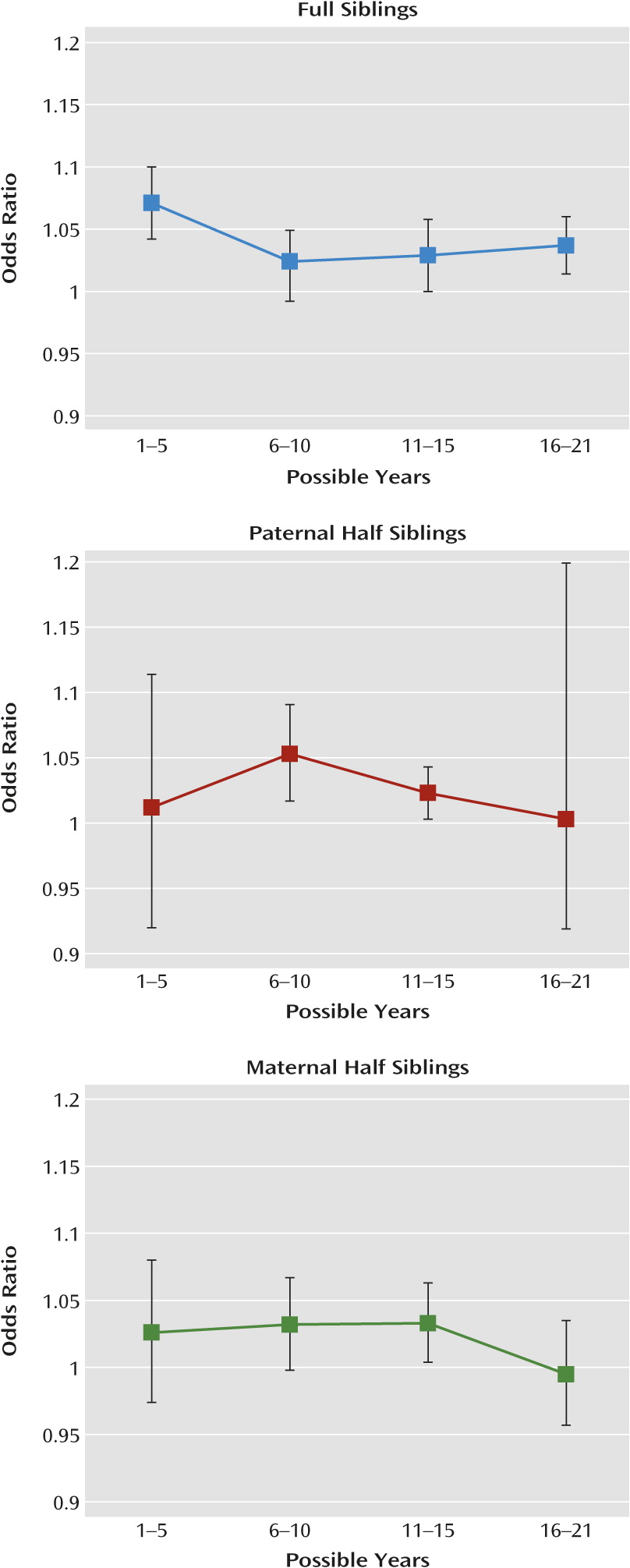

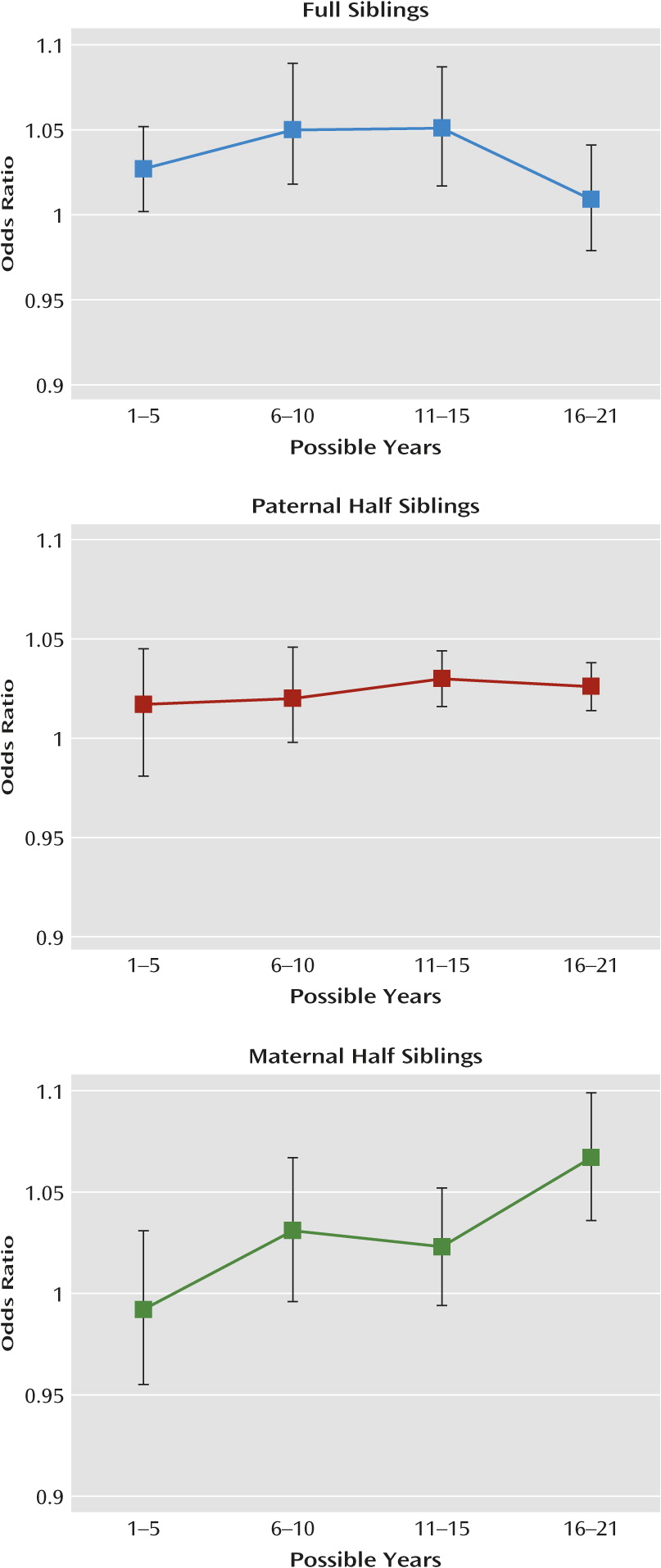

Fourth, the effect of living in the same small residential area or same municipality on resemblance for drug abuse in sibling pairs was similar to that seen for living in the same household. These results suggest that much of the shared environmental effect on drug abuse comes from community-wide influences such as drug availability, school environment, or peer group effects rather than arising largely from influences specific to individual households, such as parental monitoring or the quality of parent-child relationships. To formally test this hypothesis would require us to model the three contexts (household, small residential area, and municipality) independently; however, we could not formally do this because they were nested (e.g., living in the same household always means living in the same small residential area).

Fifth, consistent with the results of our twin sibling modeling, male-male sibling pairs were more sensitive to the effects of living in the same home or community than female-female pairs. These findings are consistent with several lines of evidence. Previous research suggests that, compared with females, males are more motivated to use psychoactive substances to conform to subgroup values (e.g., fitting in with a peer group) and more influenced by peers in their intake of drugs because they regard peer consumption as a challenge (

19,

20). In a Swedish survey of high school students, Svensson (

21) found that males had consistently higher levels of exposure to deviant peers than females and concluded that this arose largely because parents of girls monitored their offspring’s behavior and friends more closely than did parents of boys. Particularly relevant, he found the probability of drug use to be more strongly predicted by exposure to peer deviance in males than in females (

21). Both more frequent exposure to peer deviance and a greater impact of that exposure on drug use in males compared with females would likely translate into stronger peer influences in young Swedish men than Swedish women. Furthermore, in nationwide epidemiological analyses using the same definition of drug abuse employed here, we found that the risk for drug abuse in men was considerably more sensitive to neighborhood-level deprivation than it was in women (J. Sundquist et al., unpublished 2012 manuscript). Follow-up analyses in our sample pointed to two further mechanisms that might contribute to greater shared environmental influences on drug abuse in males than females. Across all the birth decades of our sample, males left home at a later age than females, with mean differences ranging from 0.6 to 3.5 years. Furthermore, in our sample, men had an earlier age at first registration for drug abuse (mean age, 27.4 years [SD=9.8]) than did women (mean age, 29.4 years [SD=11.4]) (t test for difference, p<0.0001).

Our data suggest that the greater environmental sensitivity to drug abuse of males compared with females may result from effects at several levels including peer relationships, community-wide effects, and the ages at leaving home and starting to abuse drugs.We are unaware of previous studies using similar methods to which our findings might be compared. Most relevant is a study of adolescent Finnish twins that included school classmates and so could estimate the percentage of school-based environmental variance (

22). The strongest effects were seen for alcohol and cigarette use where school-based effects accounted for 25%−30% of the variance. Our findings are also consistent with previous analyses of full sibling pairs in Sweden, which demonstrated that concordance for drug abuse was inversely related to age differences, and transmission of drug abuse was more potent from older to younger siblings than from younger to older siblings (

10).

Impact of Family Socioeconomic Status and Neighborhood Social Deprivation

Our final results examined features of the family and neighborhood environments (socioeconomic status and social deprivation, respectively) suggested by previous research to affect the risk for drug abuse and form part of the shared environment detected by our twin sibling and cohabitation analyses. Consistent with classical studies in adult populations (

11,

12) and developmental studies showing that childhood poverty predisposes to externalizing outcomes such as drug abuse (

23,

24), we found that risk for drug abuse was independently predicted by family socioeconomic status and neighborhood social deprivation.

Three features of these findings are noteworthy. First, a major problem in the interpretation of individual socioeconomic status effects is that of drift compared with selection. To what extent might low socioeconomic status and drug abuse be associated because drug abuse (or associated traits) predisposes to poverty or poverty predisposes to drug abuse? We have reduced this interpretational problem by examining adolescents living with parental figures because the association between neighborhood social deprivation and future risk for drug abuse could not plausibly result from adolescents selecting themselves into high social deprivation communities. However, our design cannot explicitly rule out family-level effects that might arise if genetic risk for drug abuse in children were correlated with poor occupation success in parents. Second, our results show that neighborhood level social deprivation affects the risk for drug abuse above and beyond family socioeconomic status effects. This finding substantially reduces the likelihood that our results arise from family-level drift and provides one potential mechanism for our cohabitation findings. Our results predict that individuals living in the same small residential area, but not the same household, would be correlated in their drug abuse risk, with the magnitude of the correlation increasing with years shared in that neighborhood. This is just what we observed. Third, socioeconomic status and social deprivation are surely not the only family- and community-level environmental factors affecting drug abuse risk in adolescence. Indeed, previous Swedish results showing greater risk for drug abuse when an older sibling has drug abuse than a younger sibling (

25) and a large body of research on peer deviance (

26–

28) both suggest the importance of direct social transmission of drug use and abuse in adolescence.