On December 14, 2012, a gunman fatally shot 20 children and six adults at an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut. This mass shooting occurred less than 6 months after James Holmes shot 70 people in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. The Aurora shooting took place a year and a half after Jared Loughner shot 18 people, including U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords, in Tucson, Arizona. In 2007, Seung-Hui Cho shot 57 people at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) in Blacksburg. In addition to horrific loss of life, these shootings shared two common elements. First, all four shooters appeared to suffer from a mental disorder. While details about the Newtown shooter’s mental health history are still emerging (

1), the Aurora, Tucson, and Virginia Tech shooters all appeared to suffer from serious mental illness (

2–

4), a category that includes conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (

5). Second, all four shooters used guns equipped with large-capacity magazines, defined as magazines holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition (

6,

7), which allow a shooter to fire more rounds before stopping to reload.

Gun control advocates view the aftermath of mass shootings as a window of opportunity to garner public support for gun control policy. Gun control policy options are limited by recent Supreme Court rulings, which prohibit comprehensive gun restrictions targeting the general population (such as handgun bans) (

8). As a result, feasible gun control policies in the United States must, as Gostin and Record noted in a 2011 commentary (

9), target specific categories of “dangerous people” or “dangerous weapons.”

The Aurora, Tucson, and Virginia Tech shootings prompted two specific types of gun control policy proposals: legislation to prevent dangerous people with serious mental illness from possessing firearms (

10,

11) and legislation to ban large-capacity magazines (

12). Efforts to enact a ban on large-capacity magazines have been unsuccessful. A federal gun restriction law for persons with serious mental illness was enacted in 2008, in response to the Virginia Tech shooting (

13). Existing federal law already prohibited gun possession for persons who have been involuntary committed to psychiatric care or adjudicated to be mentally incompetent (

14), and the 2008 law provided funding to states to report such persons to the background check system used by licensed gun dealers to screen potential gun buyers. Expanding prohibitions on gun possession by persons with serious mental illness to include persons required by a court or other legal authority to take medication or receive outpatient care for a mental disorder has also been proposed at the federal level (

11). In addition, criteria for prohibiting firearm ownership because of mental illness vary by state (

15), and some states have proposed further policies to prevent persons with serious mental illness from having guns (

16). For example, in response to the Newtown shooting, New York State passed a law requiring that medical care providers report patients who they believe are likely to harm themselves or others to law enforcement authorities, who could then seize the individual’s guns and prohibit the person from purchasing additional firearms (

16). While gun control efforts targeting those with serious mental illness are politically popular—President Obama mentioned such restrictions three times during the second presidential debate in 2012 (

17)—they have provoked controversy in the medical and public health communities. Because of the significant burden of gun violence in the United States—over 65,000 people are shot in an attack each year (

18; see also the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System,

www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars])—professionals in these fields typically support gun control initiatives. Gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness, however, have generated concern on two grounds. First, the relationship between serious mental illness and violence is complex, and much of the risk of violence in this population is attributable to comorbid factors such as substance use (

19,

20). Most persons with serious mental illness are not violent; prediction of future violence among such individuals is challenging (

21), and there is little evidence to suggest that gun restriction policies for this population accurately target the subgroup of those with a heightened risk of committing violent acts (

9). Second, it has been suggested that promotion of such policies may have the unintended consequence of exacerbating the public’s negative attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and that implementation of gun restriction policies may deter such persons from seeking help (

22,

23). Although stigma related to less severe mental disorders appears to have decreased in recent decades (

24), stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness have remained largely unchanged or possibly increased (

25,

26). The majority of persons with serious mental illness remain untreated or undertreated, and mental health experts view stigma as a key contributor to poor treatment rates (

27).

After mass shootings, the public is exposed to extensive news coverage of the shooting event, as well as coverage of gun control policies proposed in response to a shooting. Gun control advocates contend that these stories are effective in garnering support for gun control policies, and mental health advocates contend that the same stories lead to negative public attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness. Limited empirical evidence is available to test either claim. A 1996 study using national survey data from the former West Germany found that the public desire for social distance from persons with schizophrenia increased after two violent attacks on politicians by individuals with schizophrenia, both of which received extensive news media coverage (

28). However, the relationship between news coverage of violence by persons with serious mental illness and negative public attitudes has not been tested using experimental methods, and it is unclear how news coverage of mass shooting events, as opposed to news coverage of gun control policy proposals, influences public attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness or support for gun control measures. The distinction between these two types of stories is potentially important. Policy makers and advocates can influence news coverage of gun control policy responses to mass shootings by choosing which policies to promote, but they have little ability to influence coverage of the shooting events themselves.

In this study, we examined these issues in a survey-embedded randomized experiment. Participants in an online survey panel were randomly assigned to groups instructed to read one of three news stories or to a no-exposure control group. The three news stories described 1) a mass shooting event by a person with serious mental illness who used a gun with a large-capacity magazine; 2) the same mass shooting event and a proposal for a gun restriction policy for persons with serious mental illness; and 3) the same mass shooting event and a proposal to ban large-capacity magazines. This approach allowed us to test whether exposure to a news media portrayal of a mass shooting heightened negative attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness, raised support for gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness, and raised support for a ban on large-capacity magazines, compared with the control condition. We also assessed whether information describing a gun restriction policy for serious mental illness or a ban on large-capacity magazines in a news story about a mass shooting differentially affected attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness or support for gun control policies compared with the shooting event story alone.

Method

Data and Procedures

A survey-embedded randomized experiment was conducted using the GfK Knowledge Networks (KN) online survey research panel, accessed through the National Science Foundation’s Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences. The KN panel is a nationally representative online panel with 50,000 members recruited from an address-based sampling frame comprising 97% of U.S. addresses, including non-telephone, cell telephone only, and non-Internet households (

29). KN uses equal probability sampling to recruit potential panel members by mail and telephone and provides participants in non-Internet households with free Internet access and a laptop computer. Panel members complete a demographic profile survey at enrollment and respond to an average of two online surveys per month. Panel members receive small cash rewards and gift prizes for survey completion. The KN panel, which has been used in diverse medical and public health research (

30,

31), provides the unique opportunity to use experimental methods to test how news media messages affect attitudes among a nationally representative group of respondents.

The experiment was fielded over a 12-day period from May 24, 2012, to June 4, 2012. Respondents were randomly assigned either to one of three groups who read different one- or two-paragraph news stories or to a no-exposure control group. After reading the news stories, participants answered questions about their attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness, support for gun restrictions for such persons, and support for a ban on large-capacity magazines. The no-exposure control group answered these questions without reading a news story. The experiment completion rate, defined as the proportion of KN panel members randomly selected for this study who completed the experiment, was 64.0%. The recruitment rate for the KN online survey panel from which the experiment sample was drawn was 15.1%. The median completion times were 2 minutes for participants in the no-exposure control group, 3 minutes for participants assigned to read a one-paragraph news story, and 3.7 minutes for participants assigned to read a two-paragraph news story. Outlying short and long completion times may indicate failure to carefully read the news story or interruptions, respectively, during the experiment. Respondents assigned to read story 1 who took less than 1 minute to complete the experiment (N=7), respondents in groups assigned to read stories 2 and 3 who took less than 1.5 minutes to complete the experiment (N=58), and respondents in any group who took longer than 30 minutes to complete the experiment (N=97) were excluded from analysis, for a final analytic sample of 1,797 respondents.

Measures

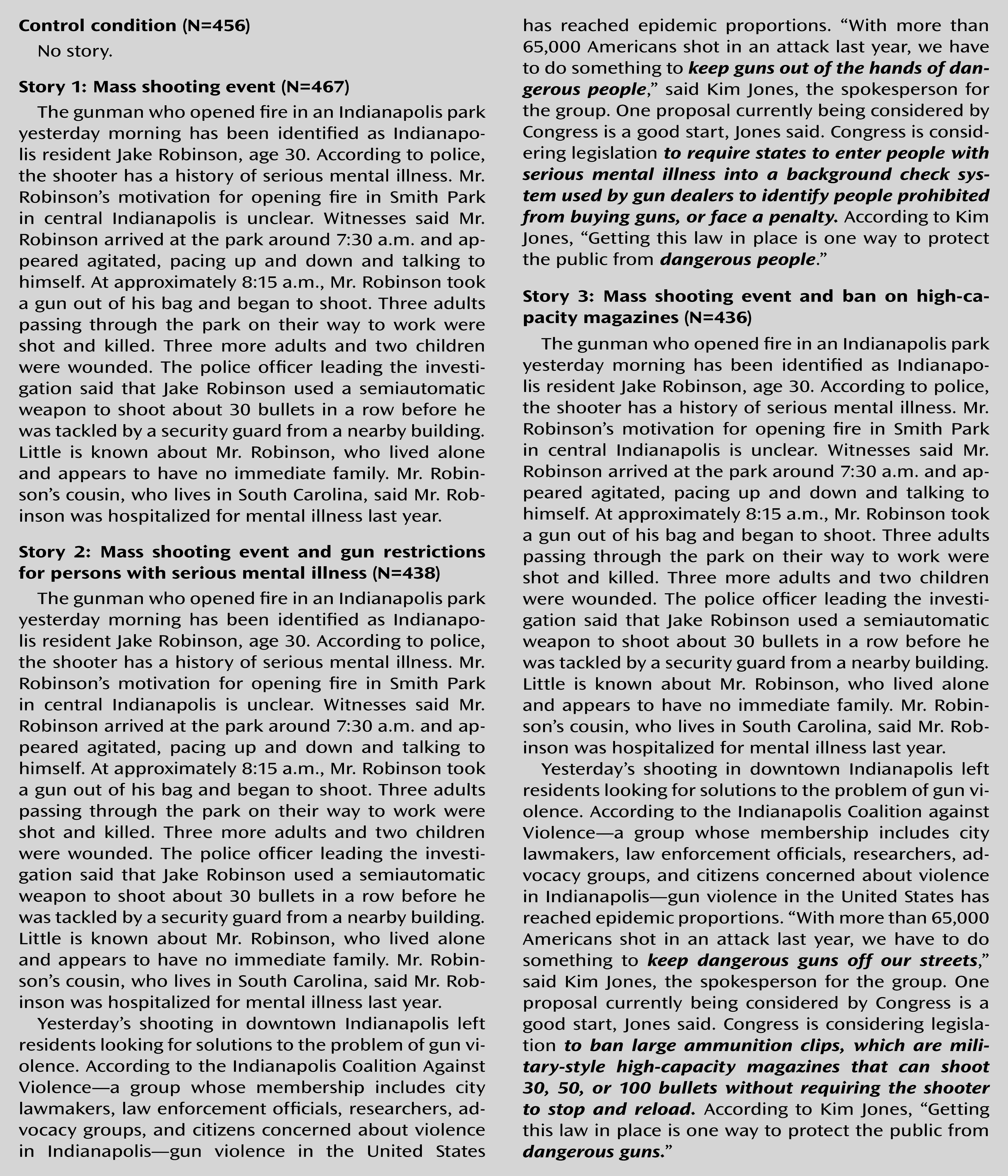

The independent variables of interest were the three randomly assigned news stories (

Figure 1). Stories were written on the basis of a content analysis of news stories about mass shootings published in U.S. newspapers. All three stories included an identical paragraph describing a mass shooting by a person with a history of serious mental illness. The paragraph in story 2 describing a proposed gun restriction policy for persons with serious mental illness was identical to the one in story 3 describing a policy proposal for a ban on large-capacity magazines, with the exception of the passages indicated in bold italic type in

Figure 1. Respondents who were assigned to read a news story viewed a screen instructing them to “Please read the following excerpt from a news story and then answer the following questions.” Respondents in the no-exposure control group, who did not read a news story, were instructed to “Please answer the following questions.”

We examined how news stories affected attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and support for gun control policies. Attitude questions, adapted from two previous surveys (

25,

32), assessed willingness to work closely with a person with serious mental illness, willingness to work near a person with serious mental illness, and perceived dangerousness of persons with serious mental illness. Policy questions, adapted from two public opinion polls (CBS News/New York Times Poll, January 15–19, 2011; and ABC News/Washington Post Poll, January 13–16, 2011), assessed support for a gun restriction policy for persons with serious mental illness and a policy banning large-capacity magazines. For all outcomes, 5-point Likert scales were collapsed to create dichotomous indicators of attitudes and policy support. In the survey instrument, attitude and policy measure block order was randomized, as was question order within blocks.

Analysis

Chi-square tests confirmed that there were no significant differences in demographic characteristics across experimental groups (

Table 1). To assess baseline support for the two gun control policies of interest and three measures of attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness, outcome measures were assessed in the no-exposure control group. Logistic regression and ordered logit models were used to estimate the effects of the three news story exposures on outcomes compared with the no-exposure control group. These models were also used to compare the effects of the news stories describing both a mass shooting event and one of the two gun control policy proposals to the effects of a story describing a mass shooting event alone. Since ordered logit models were qualitatively similar (see the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article), logistic models are presented for ease of interpretation. Because of concern that answering questions about attitudes toward serious mental illness might prime respondents on serious mental illness and thereby influence support for gun restrictions for this population, we assessed question order effects by stratifying models by question block order (see the online data supplement). Since the gun restriction results were consistent in the total sample and the subgroup that answered policy questions first (and therefore was not subject to priming by attitude questions), results are presented for the total sample. Following established conventions for survey-based experiments, we did not include covariates in these models (

33). All analyses employed survey weights provided by KN to produce nationally representative estimates (see the online data supplement). The study was determined to be exempt from review by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

Table 2 summarizes baseline attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and support for the two gun control policies in the no-exposure control group (N=456). Thirty-six percent of respondents were unwilling to work closely with a person with serious mental illness, and 30% were unwilling to have such a person as a neighbor. Forty percent of respondents believed that persons with serious mental illness are likely to be far more dangerous than the general population. Seventy-one percent of control group respondents supported gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness, and 48% supported banning large-capacity magazines.

Effects of news media messages on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness are summarized in

Table 3. All three stories heightened negative attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness. Compared with the control group, respondents in all other groups reported less willingness to work closely with or live near a person with serious mental illness. Respondents who were exposed to a story describing a mass shooting event alone also reported a higher perceived dangerousness of persons with serious mental illness than respondents in the control group. As the lower section of

Table 3 indicates, including information about proposed gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness or a ban on large-capacity magazines in a news story describing a mass shooting did not affect attitudes compared with a story describing a shooting without mentioning a policy response.

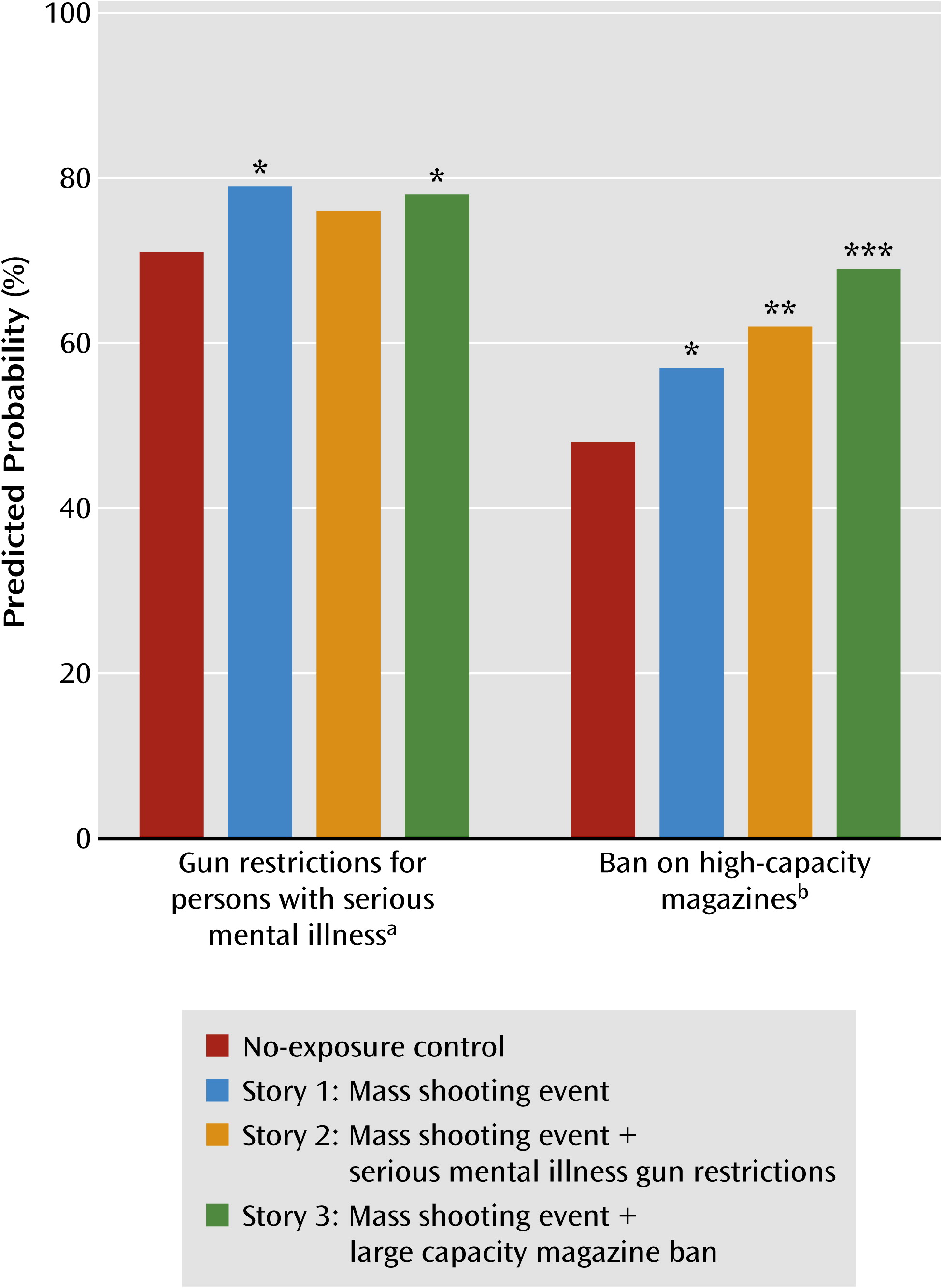

Effects of news media messages on support for gun control policies are summarized in

Table 4 and

Figure 2. As expected, a news story describing a mass shooting raised support for both gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness and a ban on large-capacity magazines compared with the control condition. Compared with the control condition, a story describing both a mass shooting and gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness raised support for a large-capacity magazine ban, and a story describing both a mass shooting event and a ban on large-capacity magazines raised support for both gun control policies. As the lower section of

Table 4 indicates, including information describing a gun restriction policy for persons with serious mental illness in a news story describing a mass shooting did not affect support for either policy compared with a story solely describing a mass shooting event. In contrast, including information about a proposed large-capacity magazine ban policy in a news story describing a mass shooting raised support for a ban compared with a story solely describing a shooting.

Discussion

News media portrayals of mass shooting events by persons with serious mental illness appear to play a critical role in influencing both negative attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and support for gun control policies. The news story describing a mass shooting event heightened desired social distance from and perceived dangerousness of persons with serious mental illness. The same story raised public support for both gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness and a ban on large-capacity magazines. Mental health experts have long suspected that news media depictions of violent persons with serious mental illness contribute to the public’s negative attitudes toward persons with serious conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (

34–

36). To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to confirm this suspicion. Study results support the opinion of former APA President Steven Sharfstein, expressed in a 2012 commentary, that negative attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness are unlikely to decline “as long as there are untreated, delusional, disheveled, threatening homeless individuals on our streets and in high-profile media examples of violence” (

34).

Our findings do not support the mental health community’s contention that messages about gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness worsen negative attitudes toward this population. However, the results have potential implications for advocates and policy makers who promote gun control policy responses to mass shootings. While news media messages about banning “dangerous guns” with large-capacity magazines raised support for such bans, messages about preventing “dangerous persons” with serious mental illness from possessing guns failed to raise support for gun restrictions for those with serious mental illness. As baseline support for such restrictions was high (70%), this finding may be due in part to ceiling effects, but it may also be due to public perceptions that persons with serious mental illness, not access to guns in society, are primarily responsible for mass shootings. Research has shown that the public is less likely to support policy efforts when they hold individuals—as opposed to society—responsible for the issue the policy seeks to address (

37). By focusing respondents’ attention on serious mental illness as a causal factor, messages about gun restrictions for persons with serious mental illness may lead the public to see mass shootings as isolated events, perpetrated by a small group of individuals, which gun control policy cannot prevent. Pew polling data suggest that the proportion of Americans who view mass shootings as “just the isolated acts of individuals” as opposed to reflections of “broader problems in society” has increased over the past 5 years, to 67% in 2012 (

38). While the majority of Americans support specific gun control measures, overall support for gun control appears to have decreased over the same period (

38).

Results of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the exposure to a one- or two-paragraph news story tested in this experiment differs from the public’s typical experience with news media content about mass shootings, which involves extensive exposure to news media messages, typically over the course of several weeks and from varied news sources, about the shooting event. Second, we did not examine the contributing effects of photographs and images that often accompany news coverage of mass shootings and may profoundly affect how the public comprehends the issue. Third, the effects of news stories were measured immediately after exposure, and it is unclear whether effects last over time. Fourth, web-based experiments have been criticized as vulnerable to sampling biases (

39). KN attempts to minimize such problems by using probability-based sampling of households, including those without landline telephones or Internet access (

29). Experiment invitations do not include the topic of the experiment, so it is unlikely that participants choose whether or not to participate according to their interests.

In the aftermath of mass shootings, the public is exposed to a torrent of news stories describing the shooter with serious mental illness, his history, and his actions during the shooting. These portrayals of the shooting events raise public support for gun control policies but also contribute to negative attitudes toward those with serious mental illness. Negative public attitudes have been linked to poor treatment rates among persons with serious mental health conditions (

40–

42). Future research should consider how mass shootings influence public support for initiatives to improve the adequacy and quality of mental health care for Americans with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The data for this study were collected by Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, National Science Foundation (grant 0818839).