The seriously mentally ill have significantly more cardiovascular risk factors, receive less appropriate medical care, and die on average 15 to 30 years earlier than the general population, mostly because of cardiovascular disorders (

1). Reasons for this physical health disparity are complex and include unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, illness-related effects (including poverty, negative symptoms, depression, etc.), unclear genetic links between mental and medical disorders, and adverse medication effects, particularly of antipsychotics (

1). Antipsychotics are key to managing schizophrenia spectrum disorders (

2) and are prescribed for various other psychiatric conditions (

3). However, their benefit-to-risk ratio is challenged by weight gain and metabolic abnormalities (

1). Several strategies help minimize adverse cardiometabolic effects of antipsychotics: healthy lifestyle interventions (

4), switching to lower-risk antipsychotics (

5), and the addition of medications that may lower body weight and/or lipid and glucose parameters (

6). Interestingly, each of these strategies reduces body weight to a similar, relatively limited extent of roughly 3 kg over 3 to 6 months (

4–

6).

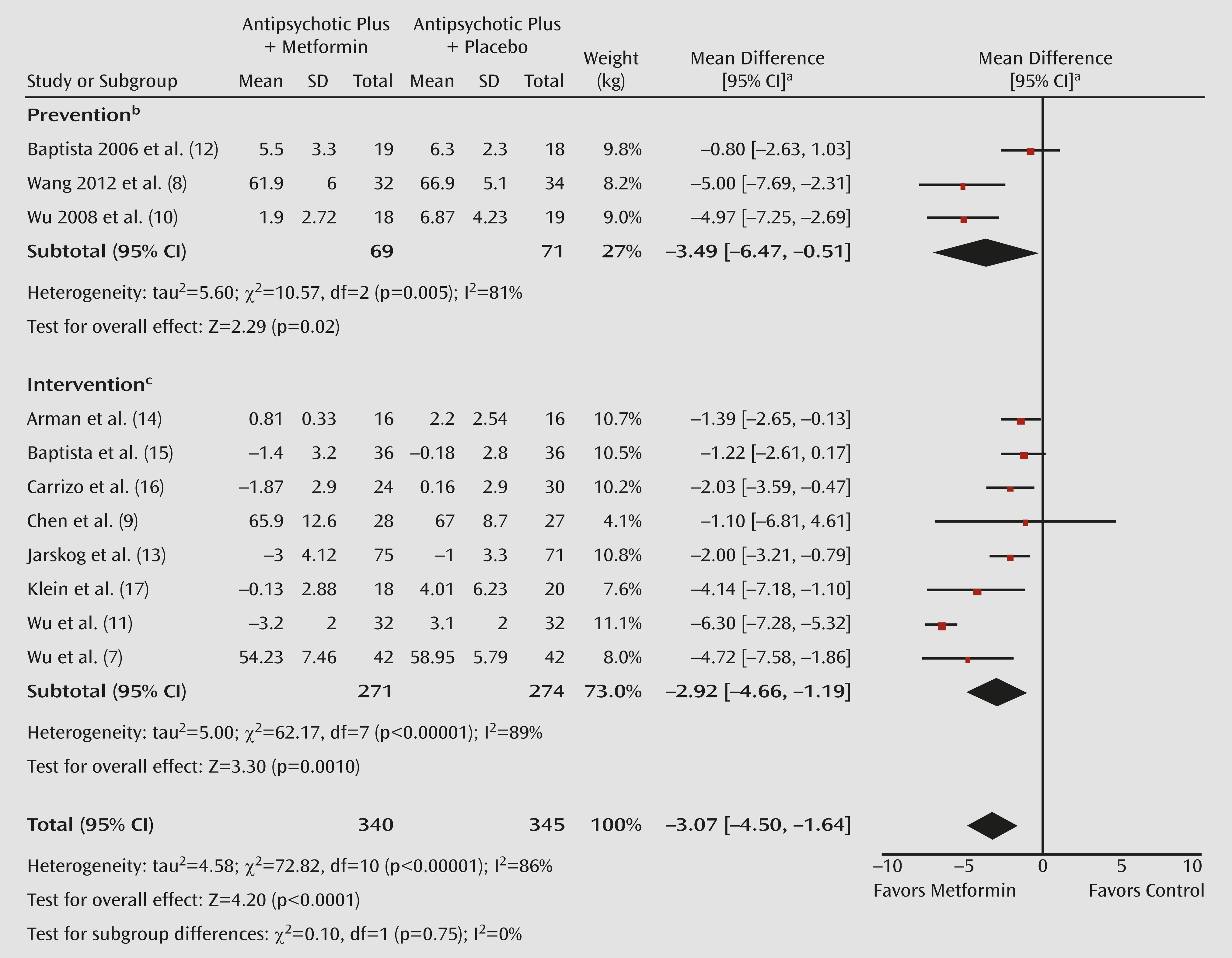

Among pharmacologic interventions, metformin, which is indicated for the treatment of diabetes in those 10 years and older, has been studied the most (

6–

9). In contrast to several weight-loss agents that have been removed from the market because of potentially serious adverse events, metformin has a well-established safety profile in both adults and youths. The most frequent side effects are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Lactic acidosis is extremely rare, especially in nonelderly populations and in those with creatinine levels <1.4. The potential risk of neuropathy as a result of chronic vitamin malabsorption is easily minimized by daily multivitamin supplementation. However, previous metformin studies targeting antipsychotic-induced weight gain have generally been small (32 to 84 participants, median=55) (

6–

12), leading to relatively wide confidence intervals (

Figure 1) and precluding mediator and moderator analyses.

In this issue of the

Journal, the study by Jarskog et al. (

13) is the largest study to date of metformin in antipsychotic-treated patients (N=146). It compared 16 weeks of 1,000 mg of metformin twice daily (mean final dose=1,887 mg [SD=292]) with placebo in antipsychotic-treated adults. Additionally, all participants received a standardized healthy lifestyle intervention, deliverable in usual care settings. Generalizability was enhanced by including patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥27 (mean=34.6 [SD=5.9]) independent of timing and amount of prior weight gain, different levels of chronicity of psychosis, comorbid psychiatric conditions, and treatment with two antipsychotics or psychiatric comedications, excluding only diabetic individuals. Furthermore, for the first time, exploratory moderator and mediator analyses of metformin’s efficacy were performed. Metformin was associated with a −3.0-kg weight loss (95% confidence interval [CI]=−4.0 to −2.0) that was significantly greater than the small weight reduction of −1.0 kg (95% CI=−2.0 to 0.0) in the placebo group. This weight reduction translated into a −0.7 (95% CI=−1.1 to −0.2) greater BMI reduction compared with placebo. However, the mean percent weight loss was only 2.8% of baseline weight with metformin compared with 1.0% with placebo, and only 17.3% and 9.8% of participants, respectively, lost ≥5% of their baseline body weight. A linear time-by-treatment interaction suggests that weight loss could possibly continue beyond 16 weeks. Additionally, the fact that the placebo group lost 1 kg over 4 months suggests that healthy lifestyle intervention can reduce some weight in motivated patients, like those participating in research. Metformin was also associated with significantly lower triglyceride and hemoglobin A

1C levels than placebo. The latter findings indicate that the weight reduction with metformin was associated with important additional benefits regarding lipid and glucose metabolism, which are closely related to the risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease (

1). Notably, metformin was well tolerated. Furthermore, younger age (<44 years old), lower BMI (<33), male sex, and nonsmoking status were associated with greater weight loss with metformin. The authors noted the inadequate power for these post hoc analyses, which likely contributed to the failure to discern significant benefits in women, who comprised only 30% of the study sample.

From this (

13) and 10 other published studies (

7–

12,

14–

17) comparing metformin with placebo in 685 antipsychotic-treated patients over a mean of 15.5 weeks, we can conclude that 1) metformin significantly reduces body weight; 2) weight loss is statistically and clinically significant but relatively modest (−3.1 kg; 95% CI=−4.5 to −1.6 [

Figure 1]); 3) despite the relatively modest weight loss, significant benefits are observed for at least some lipid and glucose parameters; 4) metformin is well tolerated; and 5) weight seems to be regained after stopping metformin (

9). However, weight loss was highly heterogeneous (p<0.00001). Weight reduction appears most pronounced in first-episode studies (

8,

10). Moreover, it is unclear whether there is a difference between metformin’s efficacy in prevention studies, in which metformin was started at the same time as the antipsychotics, and intervention studies, in which metformin was added to a stable antipsychotic regimen after significant weight gain occurred. Although weight loss with these two intervention strategies was similar, two of the three prevention trials, conducted in Chinese first-episode patients (

8,

10), had among the most favorable outcomes, whereas the third trial, conducted in South America (

12), showed no benefit. Thus, it remains unclear to what extent these findings reflect moderating effects of age, illness/treatment phase, or ethnicity versus inherent differences in prevention versus intervention approaches.

Similarly, a meta-analysis of 17 controlled trials (N=810) of healthy lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-treated adults confirmed superior weight loss with healthy lifestyle intervention after a mean of 19.6 weeks (−3.1 kg; 95% CI=−4.4 to −1.7), with similar effects for prevention and intervention studies (

4). On average, 3.6 months after stopping the healthy lifestyle intervention, benefits endured regarding weight but not BMI. In a recent, large study not included in that meta-analysis, only 3.2 kg (95% CI=−5.1 to −1.2) were lost at 18 months in 279 patients with mixed psychiatric disorders receiving tailored group or individual healthy lifestyle intervention compared with nutrition/exercise information, followed by monthly health classes (

18). Interestingly, in this unique, long-term study, participants continued to demonstrate progressive weight loss throughout the 18-month study period in contrast to studies of nonpsychiatric populations in which weight loss generally plateaus after 6 months. The authors speculated that it may take individuals with serious mental illness longer to fully engage in healthy lifestyle intervention.

Only one trial has compared metformin alone, placebo plus healthy lifestyle intervention, and metformin plus healthy lifestyle intervention (

11). In that study, significant advantages for reducing body weight and improving glucose- and insulin-related outcomes were observed for combined metformin plus healthy lifestyle intervention compared with either healthy lifestyle intervention alone or metformin alone. It is unclear whether the limited benefit of healthy lifestyle intervention in this study reflects the relatively short duration of the study or the limited engagement of severely ill patients in healthy lifestyle intervention (

12). Such comparisons warrant further study, especially since in the general population, studied in the Diabetes Prevention Program (

19), the opposite appears to be true, in that healthy lifestyle intervention was superior to metformin. Moreover, it is concerning that no healthy lifestyle intervention study (

4) and only two small metformin studies (

14,

17) have been conducted in antipsychotic-treated youths, a population increasingly receiving antipsychotics (

3) and particularly vulnerable to antipsychotic-related cardiometabolic effects (

1). Importantly, the relative efficacy and effectiveness of adding metformin versus switching to antipsychotics with lower weight gain potential, which has been shown to be effective (

5), is another pressing question. Some of these gaps are being addressed in an ongoing National Institute of Mental Health-funded study of youths between 8 and 19 years old with psychotic, mood, and autism spectrum disorders who gained clinically significant weight on antipsychotics. For the first time, addition of metformin plus healthy lifestyle intervention, switch to a lower-risk antipsychotic plus healthy lifestyle intervention, and healthy lifestyle intervention alone will be directly compared (

http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00806234). Findings are expected in 2014.

In summary, metformin augmentation of antipsychotics is an evidence-based option to reduce antipsychotic-associated cardiometabolic effects. However, the overall weight loss is modest compared with the weight generally gained on antipsychotics (

1,

4,

6), and metformin should likely only be added after a clinical trial of a psychosocial intervention for weight loss has proven to be ineffective. Such interventions include psychoeducation focused on nutritional counseling, caloric expenditure, and portion control; behavioral self-management including motivational enhancement; goal setting; regular weigh-ins; self-monitoring of daily food and activity levels; and dietary and physical activity modifications (

20). More placebo-controlled trials of metformin, at least in adults, are not likely to advance our knowledge regarding strategies to control antipsychotic-associated weight gain, unless they last at least 6 months, are sufficiently large to identify mediators and moderators, and/or have a discontinuation phase. Conversely, studying metformin in comparison to or combined with other strategies is much needed. Additional comparators may include antipsychotic switching, topiramate, which is the second most effective medication for antipsychotic-related weight gain (

6), or metformin plus topiramate in patients insufficiently benefiting from metformin. Furthermore, the two recently approved antiobesity medications, lorcarserin and phentermine plus topiramate-extended release, should not only be compared with placebo but also with metformin in antipsychotic-treated patients. Finally, not all antipsychotic-treated patients benefit sufficiently from metformin. It is essential to identify the best candidates for metformin. Future studies should ideally include patients with different durations of illness and ethnicities, stratifying randomization by first- versus multiepisode schizophrenia and Asian compared with non-Asian race, so that these moderators can be assessed. Similarly, a study comparing prevention versus intervention approaches would be informative. It is hoped that future studies will help clinicians make individualized management decisions for antipsychotic-treated patients that maximize psychiatric benefits while minimizing adverse health consequences.