Offspring of trauma survivors are at increased risk for mental and physical illness (

1–

3). Although studies of the intergenerational transmission of trauma traditionally emphasize the influence of exposure (

1,

2), there is evidence for the effects of parental trauma-related psychopathology. Parental posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but not Holocaust exposure, is associated with alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function, including enhanced cortisol suppression following dexamethasone administration (

4) and lower baseline cortisol levels (

5), in offspring. Cortisol levels in infants of mothers who developed PTSD following exposure to the September 11th, 2001, World Trade Center attacks were lower than those of mothers who did not develop PTSD (

6). These neuroendocrine findings in offspring of trauma survivors are similar to observations in Holocaust survivors and other trauma-exposed persons with PTSD (

7).

Transmission of effects from parents to children is thought to be mediated by developmental programming of glucocorticoid signaling (

8). Variations in maternal care in rats predict hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression and levels of cytosine methylation of the exon 1

7 promoter of the rat glucocorticoid receptor gene (

9). Studies of postmortem human brain tissue have demonstrated an association between methylation status of the orthologous exon 1F promoter region in the human glucocorticoid receptor gene

(NR3C1) in the hippocampus and history of childhood abuse (

10). This same association between childhood adversity and GR-1

F methylation has been observed in whole blood (leukocytes) (

11,

12).

Although the majority of studies of transgenerational transmission of trauma effects highlight maternal influences, few studies have directly compared maternal and paternal effects on the offspring (

1,

2). Among offspring of Holocaust survivors, maternal PTSD was associated with increased risk for developing PTSD, whereas paternal PTSD was associated with greater risk for major depressive disorder, an effect that emerged after controlling for the effect of maternal PTSD (

13). Maternal PTSD has been more strongly associated with lower cortisol levels in Holocaust offspring compared with paternal PTSD (

14), and we recently demonstrated that maternal PTSD is related to increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity (

15). In a longitudinal study of adopted children, differential and interacting maternal and paternal effects on children’s cortisol variability was reported (

16). Inconsistent, over-reactive parenting by mothers predicted lower cortisol variability, whereas a similar parenting style among fathers generally predicted higher cortisol variability in offspring but only in the absence of low maternal cortisol variability. Similarly, we recently observed that both 24-hour urinary cortisol excretion and cortisol nonsuppression following dexamethasone administration were higher in offspring with paternal PTSD in the absence of maternal PTSD but lower in those with maternal PTSD (

15). In the present study, we examined the distinct influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on DNA methylation of the exon 1

F promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR-1

F) gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. We hypothesized that maternal PTSD would be associated with lower offspring GR-1

F promoter methylation and that paternal PTSD would be associated with higher GR-1

F promoter methylation. We further hypothesized that GR-1

F promoter methylation would inversely correlate with glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity.

Discussion

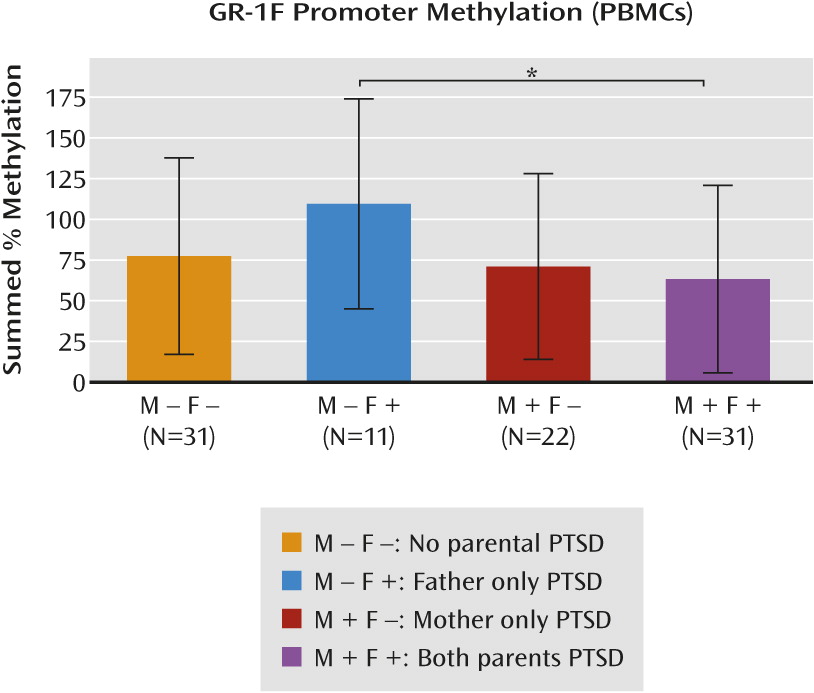

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to demonstrate alterations of GR-1

F promoter methylation in relation to maternal and paternal PTSD. Maternal PTSD moderated the effect of paternal PTSD on GR-1

F promoter methylation. Paternal PTSD, only in the absence of maternal PTSD, was associated with higher levels of GR-1

F promoter methylation, while offspring with both maternal and paternal PTSD displayed the lowest level of methylation. Although the sample size was limited, findings are consistent with those of previous reports on the effects of parental PTSD on offspring phenotype. In a different cohort of Holocaust offspring, we observed that maternal PTSD significantly enhanced the risk for PTSD, while paternal PTSD significantly elevated the risk for depression when controlling for maternal PTSD (

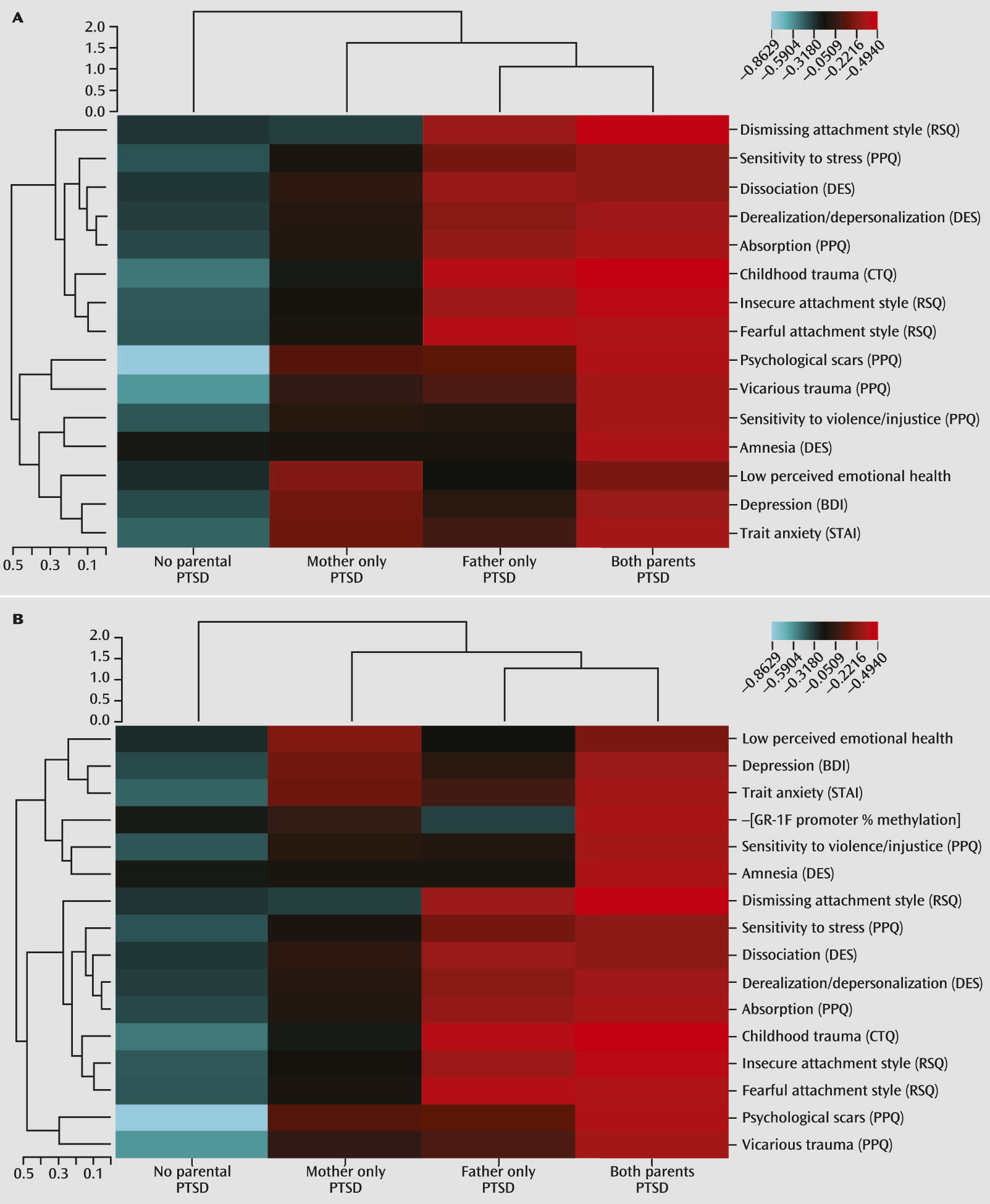

13). The hierarchical clustering analysis similarly revealed that maternal and paternal PTSD were associated with different offspring psychological characteristics and that lower GR-1

F promoter methylation was specifically associated with maternal PTSD.

In this study, phenotypic clustering analysis also demonstrated an association of paternal PTSD, but not maternal PTSD, with childhood abuse and neglect, which is consistent with findings in offspring of male war veterans with PTSD (

28). It is notable that the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire assesses a range of potentially traumatic experiences but does not identify the perpetrator. Thus, it cannot be concluded that fathers with PTSD are more likely than mothers to abuse their children. The finding of relatively higher GR-1

F promoter methylation with paternal PTSD (in the absence of maternal PTSD) is consistent with a previous finding in postmortem human hippocampus of an association between higher GR-1

F promoter methylation and childhood abuse (

10), as well as with more recent findings of an association of higher methylation of specific CpG sites within the GR-1

F promoter in whole blood (leukocytes) with lower parental care, higher childhood maltreatment, and parental loss in healthy adults (

11) and with childhood sexual abuse and extent of childhood maltreatment in individuals with borderline personality disorder (

12). The type, severity, chronicity, and developmental stage of adversity, as well as sex of the parent and offspring, may be critical for these associations. Unfortunately, our sample size was too small to investigate the influence of these factors.

The hypothesis that GR-1

F methylation would be associated with early adversity was based on an interpretation of differences in offspring methylation status on the orthologous promoter region in the rat, based on naturally occurring variations of maternal care (

9). The implication of rodent studies of the effect of maternal care on offspring is that early-life challenges, including variations in parental care, are capable of producing enduring epigenetic changes resulting in sustained phenotypic outcomes in the offspring, including altered stress reactivity. The impact of these effects will depend on context and the degree to which the resulting phenotypic variation meets the particular demands of the prevailing environment. Chronic stress produces variations in the maternal care of the rat (i.e., reduced pup licking/grooming) that are associated with methylation-mediated decreased hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor expression and increased HPA responses to stress (

29,

30). This increased stress reactivity may be considered adaptive in highly adverse conditions (

31). In Holocaust offspring, a parent may have similarly primed his or her offspring for a highly threatening environment that in a post-Holocaust context results in an overgeneralized and exacerbated fear response.

Although offspring with paternal PTSD reported more childhood trauma, the effect of paternal PTSD differed depending on the presence of maternal PTSD. This raises the possibility of indirect effects, such that PTSD in one parent may affect the parenting of the other or create a qualitative shift in the family environment. For example, paternal PTSD has been associated with higher levels of family conflict in this sample (

15). It seems that paternal PTSD alone produces effects such as higher cortisol excretion, reduced glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, and higher GR-1

F promoter methylation, similar to those seen in other samples with major depressive disorder and history of childhood abuse (

10,

32,

33). When both parents have PTSD, offspring phenotype, including lower GR-1

F promoter methylation, appears instead to resemble the biology of PTSD risk or expression (

7,

34). It is possible that when both parents are traumatized or express symptoms, there is no buffer for the child, resulting in an unmediated experience of constant or repeated threat imposed by the unpredictability of parental behavior and resulting in the expression of hypervigilance in the offspring. Because most of the offspring in the present study were raised in the social context of the late 1940s–1960s, with families structured around traditional gender roles, mothers were more likely to be the primary caregiver, whereas many offspring described fathers who worked long hours and were somewhat distant from the family unit. Thus, social context may moderate the processes underlying the intergenerational transmission of trauma (

35). While we were able to show different offspring phenotypes based on maternal compared with paternal PTSD, delineations of early parent-child and interparental interactions that may mediate these relationships require further empirical investigation.

The functional relevance of the differences in methylation is apparent in the negative correlation between GR-1

F promoter methylation and expression of the respective transcript (i.e., GR-1

F transcript). Furthermore, lower levels of GR-1

F promoter methylation were associated with enhanced glucocorticoid negative feedback inhibition assessed by the dexamethasone suppression test, suggesting that the epigenetic status in blood of offspring resulting from parental PTSD reflects neuroendocrine function. We previously suggested that glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity as assessed by the cortisol response to dexamethasone may be a relatively stable marker of risk in Holocaust offspring (

4,

15). Furthermore, it has previously been suggested that glucocorticoid receptor binding in peripheral tissue (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) is sufficiently stable to associate with PTSD risk as a trait (

36). To our knowledge, there has only been one other study demonstrating an association between GR-1

F promoter methylation and glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity (

25); however, associations with reduced negative feedback inhibition have been observed in association with higher methylation of specific CpG sites on the GR-1

F promoter (

11). A similar moderating effect of maternal PTSD on the effects of paternal PTSD was observed in the same participants examined in the present study with respect to both the cortisol response to dexamethasone and 24-hour urinary cortisol excretion (

15). A maternal PTSD effect associated with increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity in peripheral tissue was also observed (

15). Since DNA methylation is a chemically stable epigenetic mark, these findings suggest that the differences in GR-1

F promoter methylation might mediate the variation in glucocorticoid receptor function and HPA-axis feedback sensitivity that associate with the transgenerational transmitted effects of Holocaust-related psychopathology trauma on the risk for PTSD in the offspring.

The exact mechanisms underlying this transgenerational transmission are unknown. The offspring in this sample were conceived after, and in some cases decades after, parental Holocaust exposure. However, studies with rodents demonstrate that preconception paternal stress can influence behavior and biology in progeny through epigenetic changes in sperm (

37), such that germ-line transmission of epigenetic marks associated with PTSD risk is possible. Additionally, variations in the methylation status of the GR-1

F promoter can occur in association with pre- as well as postnatal exposures (

10,

11,

38,

39). Moreover, stress in one parent may also exert indirect effects on offspring through its influence on the other parent (e.g., paternally driven maternal effects) (

40). Finally, there may be direct effects on parent-offspring interactions that are ultimately reflected in the epigenome.

Holocaust offspring who met criteria for PTSD were excluded from this study in order to better focus on effects associated with transmission of vulnerability and not expressed PTSD. While the presence of psychiatric disorder represents a clear expression of illness vulnerability, it is also useful to identify more subtle or cumulative effects resulting from maternal and paternal PTSD and their interaction. The psychological constructs in the clustering analysis demonstrate aggregate phenotypic differences in both the early environment of the offspring and more distal indicators of offspring distress and functioning. In addition to higher reported levels of childhood trauma, paternal PTSD was associated with a dismissing, fearful, or insecure attachment style, as well as more dissociative experiences and greater sensitivity to violence. Maternal PTSD was associated with more self-reported symptoms of depression and higher trait anxiety, which is consistent with findings of an association between maternal Holocaust exposure and higher levels of psychological distress in offspring (

24). It is possible that the higher self-reported depression symptoms associated with maternal PTSD are best understood as an index of distress or negative affectivity, particularly in a sample in which PTSD is excluded and with low rates of current major depressive disorder.

Such fine-grained phenotypic distinctions suggest important differences in the expression and effect of maternal and paternal PTSD on offspring phenotype that contribute to psychiatric vulnerability. Research on the intergenerational transmission of trauma requires nuanced assessment of both potential mechanisms of transmission (e.g., parenting and attachment) and indicators of vulnerability and phenotypic differences that represent cumulative effects of being raised from birth by traumatized, symptomatic parents.