Persons with severe mental illness, defined as those with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder, have a life expectancy gap of 15–20 years, which is mostly explained by natural causes of death (

1,

2). The underlying causes of this excess mortality are not completely understood, but previous research has pointed to higher prevalences of noncommunicable physical diseases (e.g., diabetes and cardiovascular disease) (

2–

4), poor quality of medical health care (

5–

7), dysregulation of stress response systems (

8), and adverse health behaviors (e.g., smoking and substance abuse) (

9,

10).

Although infections are common conditions and leading causes of death (

11), it remains unclear whether poor prognosis after infection contributes to the excess mortality among persons with severe mental illness. Identification of higher mortality after infection among persons with severe mental illness may lead to health care interventions that could reduce the inequality in health outcomes for this group of patients. Deaths due to infections are unnecessary and are potentially preventable by affordable and readily available treatment. Three studies have shown that persons with severe mental illness have three to seven times the risk of having an infection-related cause of death compared with persons without severe mental illness (

2,

12,

13), but the quality of routinely collected information on causes of death is known to be poor (

14). Furthermore, studies of causes of death cannot help us understand whether persons with severe mental illness are more prone to catching an infection or to dying when they have an infection. Distinction between these two types of risks is important, as they call for different clinical interventions.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relative risk and the absolute risk of dying within 30 days after hospitalization for an infection among persons with severe mental illness as compared with persons without severe mental illness in a large population-based cohort between 1995 and 2011.

Method

We conducted a population-based cohort study using data from nationwide Danish registries. These registries contain information on Danish citizens, and all data are recorded with reference to a 10-digit civil registration number, a unique personal identification number assigned to all residents of Denmark. This number provides accurate linkage of information at the individual level (

15). All diagnoses in the Danish national registers are classified according to the Danish-language version of ICD-8 before 1994, and according to ICD-10 starting January 1, 1994.

Procedures

Study population and all-cause mortality.

We used the Danish Civil Registration System (

15) and the Danish National Patient Register (

16) to establish our study cohort. The Civil Registration System includes information on gender, date of birth, and continuously updated information on vital status and migration since 1968. Our study population consisted of all persons who were born in Denmark, were at least 15 years old, and had a first-time hospitalization for infection between 1995 and 2011. All deaths occurring within 30 days or 12 months after the date of a first-time hospitalization for an infection were identified from the Civil Registration System between 1995 and 2011.

Psychiatric illness.

Information on psychiatric disorders was obtained from the Danish Psychiatric Central Register (

17), which contains information on all admissions to psychiatric hospitals in Denmark since 1969 and outpatient mental health contacts (comprising all contacts with psychiatric ambulatory care) since 1995. All psychiatric admissions in Denmark with a diagnosis of severe mental illness (defined as those with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder) recorded between 1969 and 2011 were identified. Outpatient contacts (excluding psychiatric emergency contacts) from 1995 onward were also included.

Infections.

Information on hospitalizations for infections was obtained from the National Patient Register (

16), which contains information on all Danish medical inpatient hospital contacts since 1977 and outpatient contacts since 1995. All first-time inpatient hospitalizations for infections (i.e., primary and secondary discharge diagnoses of infection) between 1994 and 2011 were identified and categorized according to the type of infection causing the hospitalization (see the appendix in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). To avoid including rehospitalizations, we excluded persons admitted with an infection during the year preceding the start of follow-up.

Deaths due to infectious causes.

Information on causes of death was obtained from the Danish Register of Causes of Death (

14), which contains information on all deaths of Danish citizens and residents between 1970 and 2010. Causes of death due to infections were divided into the same categories as the hospital contacts for infections. All deaths due to infectious causes within 30 days after admission for an infection were identified between 1995 and 2010.

Potential moderators.

Information on diabetes was obtained from the Danish National Diabetes Register (

18) between 1995 and 2011. The applied algorithm for identifying individuals with diabetes has been shown to have a sensitivity of 86% and a positive predictive value of 89% (

18); it has been described in detail elsewhere (

4,

18). All contacts based on a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease and all contacts based on diagnoses of chronic diseases included in the Charlson comorbidity index (

19) were identified from the National Patient Register between 1977 and 2011. All contacts based on a diagnosis of substance abuse (i.e., alcohol-related or drug-related substance abuse, excluding tobacco abuse) were identified from the Psychiatric Central Register or the National Patient Register between 1969 and 2011. Information on education level was obtained from Statistics Denmark (

20), which maintains a data bank with socioeconomic information on all citizens in Denmark from 1980 onward. As education level was unknown for a substantial proportion of individuals over age 70, we adjusted for education level in a sensitivity analysis among those under age 70.

Statistical Analysis

We included persons over age 15 in the study cohort when they were admitted with a first-time infection during the study period, and these individuals were censored 30 days after the admission, on the date of death, on the date of emigration, or on April 30, 2011, whichever came first.

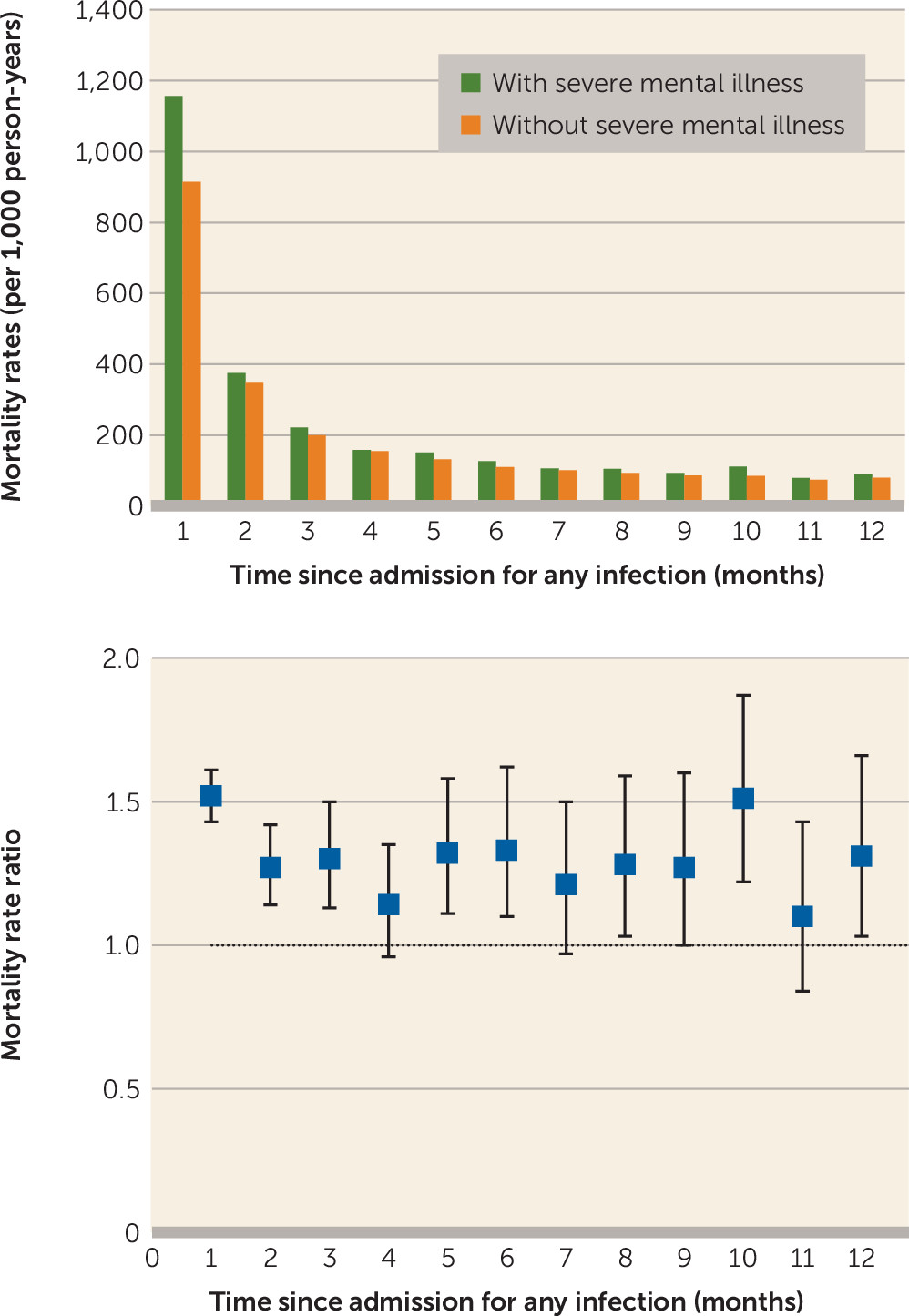

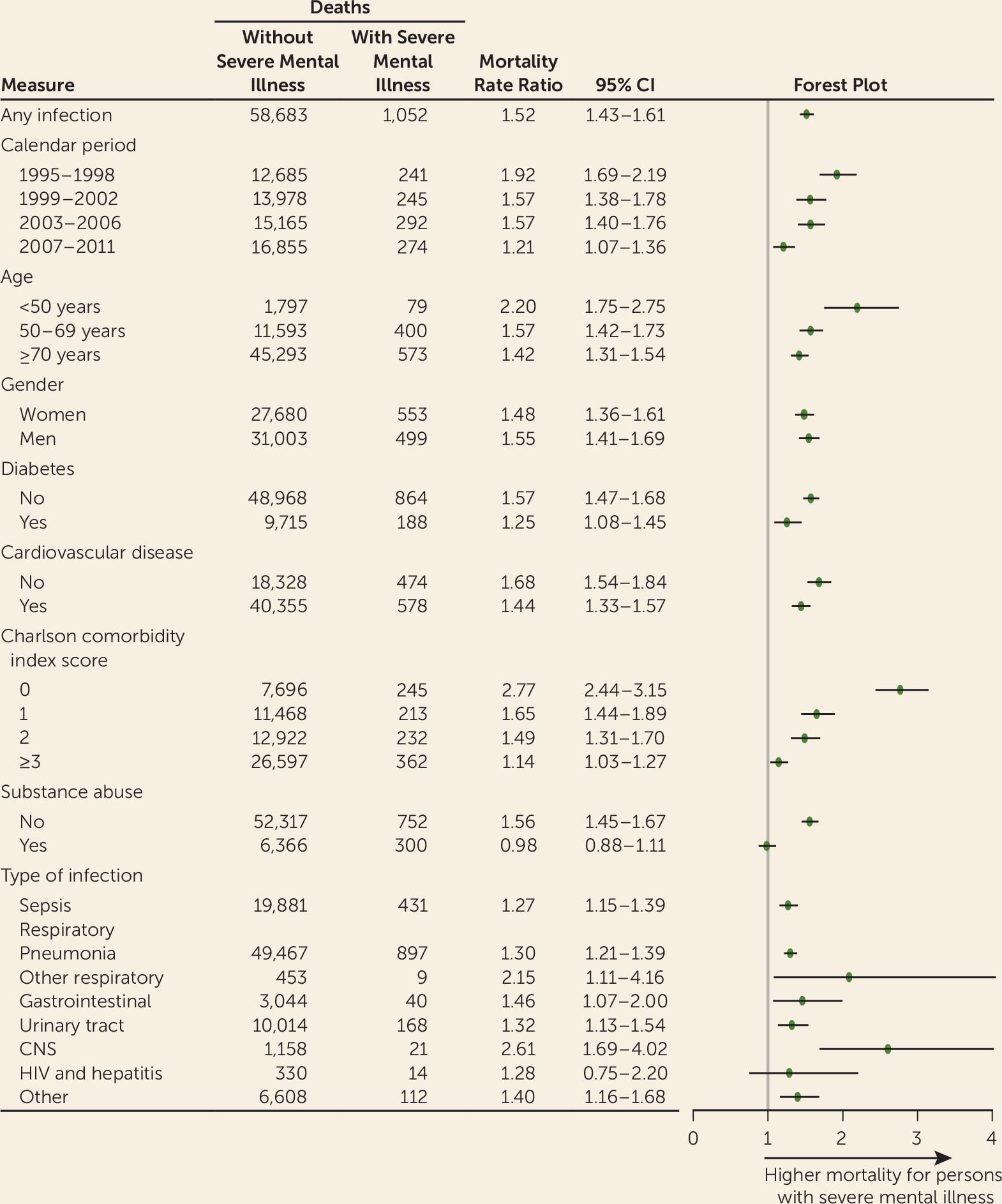

Mortality rate ratios were calculated for the all-cause 30-day mortality after any infection and for different categories of infections for persons with severe mental illness as compared with persons without. We also performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we evaluated the 30-day mortality rate ratio among the subpopulation that was over age 18 at the time of infection diagnosis. Second, we evaluated the 30-day mortality rate ratios for the periods before and after discharge from the hospital. Third, we evaluated separate effects of infection on persons with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Fourth, we evaluated the mortality rate ratios for the all-cause mortality for each month of the first year after an admission for infection. Finally, we evaluated the mortality rate ratios for death due to infectious causes, as stated in the death certificate, within 30 days after a hospitalization for infection. All mortality rate ratios were adjusted for age, gender, and calendar period.

We fitted three models of survival analysis to the all-cause mortality outcome after admission for any infection and evaluated them for four different time periods during the 30 days after admission for an infection: 0–30 days, 0–7 days, 8–14 days, 15–21 days, and 22–30 days. The first model included demographic characteristics (age and gender) and calendar period, and we additionally included education level as a sensitivity analysis. The second model added clinical comorbidity (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and Charlson comorbidity index score), and the third added substance abuse.

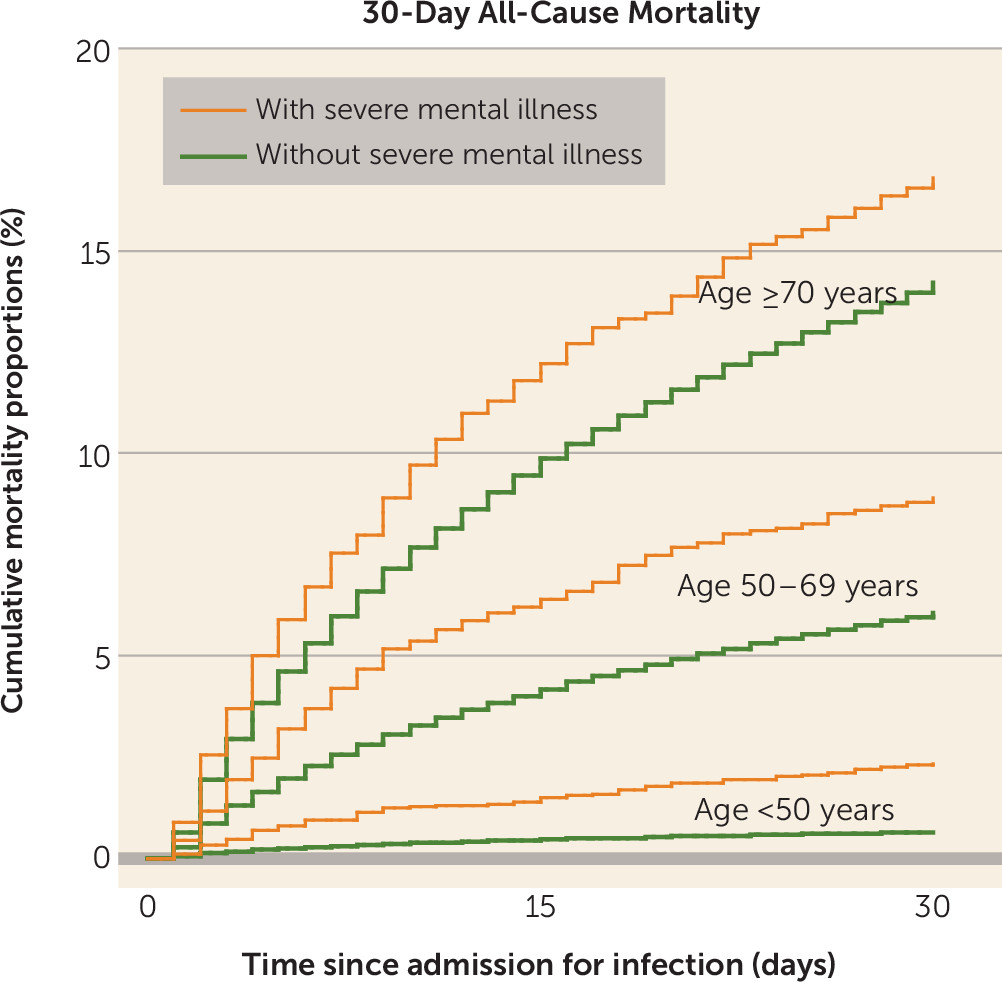

All-cause mortality was analyzed with time since infection diagnosis as a time scale, and cumulative mortality proportions for up to 30 days after the date of admission were estimated by Kaplan-Meier curves. The risk of dying within 30 days after admission for any infection was estimated for persons with and without severe mental illness. In addition, we calculated risk differences (i.e., cumulative mortality proportion differences) between persons with and without severe mental illness for each age category.

Data were analyzed by using log-linear Poisson regression analysis, with the logarithm of the person-years as an offset variable, using Stata, version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.). All variables except gender were treated as time-dependent variables. Adjustments for age and calendar period were performed using 5-year age bands and 4-year time bands, respectively. The assumption of piecewise constant intensity for the Poisson regression model was checked. The p values and 95% confidence intervals were based on likelihood ratio tests.

Discussion

This large population-based study showed that the mortality was high after hospitalization for infection for everyone, but it was substantially (52%) higher during the 30 days after admission for an infection for persons with severe mental illness than for those without. The excess risk of death after infection depended on the type of infection, with the increase in risk ranging from 27% after admission for sepsis to 161% after admission for a CNS infection. Depending on age, 1.7 to 2.9 more deaths were observed per 100 persons with a history of severe mental illness within 30 days after admission for infection when compared with 100 persons without such a history.

Our study has several strengths, including the large population-based cohort, which was followed without loss to follow-up. Bias due to selection of study subjects, loss to follow-up, and nonresponse is therefore unlikely to explain our findings. The data we used on psychiatric hospital contacts, hospitalizations for infection, and all-cause mortality have high validity and completeness, which minimizes any potential information bias. The diagnosis of schizophrenia has been shown to have a sensitivity of 93% and a positive predictive value of 87% in the Danish Psychiatric Central Register (

21). The diagnosis of infection has been shown to have a positive predictive value of 95% in the National Patient Register (

22), and the completeness of registration of death is considered to be close to 100% in the Civil Registration System (

15).

This study was, however, limited by the lack of some important clinical information. For example, we had access to information only on persons who were treated for their infection in a hospital setting. Our results therefore may not apply to persons with less severe infections who were treated in primary care settings or in psychiatric wards or were left untreated. We did adjust for several potential intermediate variables, and these analyses did not change the results significantly. However, substance abuse and comorbid physical diseases may be underdiagnosed among persons with severe mental illness (

23,

24), which could lead to an underestimation of the excess mortality accounted for by these intermediate variables. We were unable to include information on adverse health risk factors that could potentially be associated with mortality, such as body mass index, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and low socioeconomic status, as these data either were not available or were substantially affected by missing information. Consequently, residual confounding cannot be excluded. This study was conducted in a country with free and equal access to health care, and therefore our results may be generalizable only to countries with similar health care systems. Because receipt of care among persons with severe mental illness may be somewhat lower in countries in which access to health care depends on health insurance (

25), our results may represent conservative estimates of the excess mortality after an infection for persons with severe mental illness.

Although previous studies have shown that infections are a predictor for subsequent development of severe mental illness (

26–

28) and that severe mental illness is a risk factor for infections (

12,

13), to our knowledge no studies have been published in the psychiatric literature on prognosis after admission for infections. A few studies have reported that the risk of death from pneumonia (

12,

13) and from any infection (

2) is three to seven times higher in persons with severe mental illness than in those without. However, these studies evaluated the mortality rate ratios exclusively on the basis of information from death certificates. The quality of cause-of-death registrations is known to vary on death certificates (

14), which makes the cause-specific mortality prone to bias if the certificate registrations vary between persons with and without severe mental illness. Also, the significance of infection for the risk of premature death is likely to be underestimated when considering death certificates only, since infection may contribute to fatal conditions other than infection that may be recorded as the cause of death.

Our study is the first to show, on the basis of highly valid data on all-cause mortality from the Civil Registration System, that all-cause mortality is increased after hospitalization for any infection in persons with severe mental illness. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis using data from the Danish Register of Causes of Death to evaluate the risk of infectious death as stated in death certificates in our hospitalized cohort. Persons with severe mental illness had a 2.6-fold higher risk of infectious causes of death than those without severe mental illness. This ratio is lower than that previously reported in a Nordic study of persons with recent onset of psychiatric illness, which found that the risk of death due to infectious causes was two to five times higher for persons with a psychiatric disorder than those without (

2). Yet the Nordic study included a younger cohort and studied the long-term outcome for persons with severe mental illness, whereas our study was restricted to a 30-day period after admission for infection among persons with severe mental illness. Thus, these estimates are hardly comparable.

The presence of medical comorbidities is associated with poorer outcome for persons from the general population hospitalized for an infection (

29,

30), and persons with severe mental illness generally have higher rates of all types of chronic physical illnesses (

31). Also, severe mental illness is known to be associated with substance abuse (

9), which is also independently associated with poorer outcome after infections (

32). However, adjusting for these variables in our analyses decreased the risk only slightly, which suggests that other explanations for this excess mortality are more likely. Persons with severe mental illness could potentially have received suboptimal care for their infection or could have experienced treatment delays within the health care system, leading to greater severity of the infection. Several studies have shown that persons with severe mental illness generally receive suboptimal treatment for medical diseases, although this has only been documented for noncommunicable diseases (

5–

7). It has also been shown that persons with severe mental illness are likely to be discriminated against (

33) and to experience “diagnostic overshadowing” (i.e., misattribution of physical illness signs and symptoms to concurrent mental disorders), leading to poorer-quality physical health care (

34). It is notable that our study includes only persons who have already been identified, diagnosed, and hospitalized for their infection by the health care system. Consequently, the health care contact has already been established and antibiotic treatment and supportive care are presumably available and do not depend on whether the patient has a history of severe mental illness.

Nevertheless, treatment of persons with severe mental illness can pose a difficult challenge for clinicians, and discrimination and suboptimal delivery of in-hospital and follow-up care may therefore play an important role in the inequality in outcome (

5–

7,

33). In addition, many persons with schizophrenia have cognitive and social dysfunctions that could hamper self-care, engagement in treatment, and adherence (

35). Thus, persons with severe mental illness may have a higher risk of premature death if they present to health care professionals with symptoms of infection late in the disease course, self-discharge prematurely from hospital, or fail to follow up appropriately after hospitalization.

Interestingly, this study showed that the highest excess risk appears after admission for a CNS infection. This may be explained by delayed detection of CNS infections among persons with severe mental illness because recognition of deviations in neurological behaviors in this group may be confounded by baseline cognitive status, psychotic symptoms, or abnormal behavior.

Finally, increased vulnerability or even familial liability to infection has been suggested to exist among those with severe mental illness (

36). Such vulnerability could possibly lead to more severe and treatment-resistant infections (

36) and thereby increase the risk of dying after an infection. In line with this hypothesis, we found that the mortality among persons with severe mental illness tended to remain significantly elevated in the year after admission for an infection compared with the mortality among persons without severe mental illness, even after adjusting for potential intermediate variables. This suggests that persons with severe mental illness who have an infection or are hospitalized for one constitute a vulnerable group with a persistently high risk of premature death, independent of co-occurring noncommunicable physical illnesses. Because we studied only first-time hospitalizations, we do not know whether persons with severe mental illness and a first-time hospitalization for an infection are in fact susceptible to repeated hospitalizations for infections and subsequent premature death.