Over the past three decades, psychiatry’s focus has shifted away from the couch and toward the computer. Gone are the days when psychiatrists took notes in longhand—or listened without taking any notes at all. Whatever their theoretical orientation, today’s psychiatrists are faced with the reality of the electronic health record, a key provision of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act of 2009, which mandated that all health care providers billing Medicare adopt and demonstrate “meaningful use” of electronic health records by 2014. Those who work in hospital settings—including psychiatric residents and their on-site supervisors—must find a way to effectively incorporate electronic health records into the practice of psychiatry.

Electronic charting may interfere with the quality of the doctor-patient relationship and, ironically, diminish the accuracy and meaningfulness of medical records.

Dr. A is a third-year resident in the Women’s Life Center, a reproductive psychiatry outpatient clinic at UCLA. After spending an hour with a new patient, Dr. A presented the patient to her attending. Reading from her almost completed note (typed during her initial interview), Dr. A stated that the patient was a 36-year-old married mother (gravida 3, para 1) of a 3-year-old son, who came in for a pre-pregnancy consultation after a recent miscarriage. She had a history of major depression and anxiety, treated in the past with sertraline. The patient had self-discontinued the sertraline because of concerns about possible risks to a fetus. Pertinent symptoms included depression, with episodic tearfulness, irritability, poor concentration, inattentiveness, and anhedonia. The patient was not suicidal and had no history of mania. Although she was overwhelmed with daily responsibilities, the patient stated that she was able to care for her toddler. Her husband was supportive but worked two jobs and had limited time to help. Dr. A described the case as rather straightforward, concluding that the patient was moderately depressed but affectively stable, and fully functional. Her initial suggestion was that the patient be restarted on sertraline and seen in 1 month for follow-up.

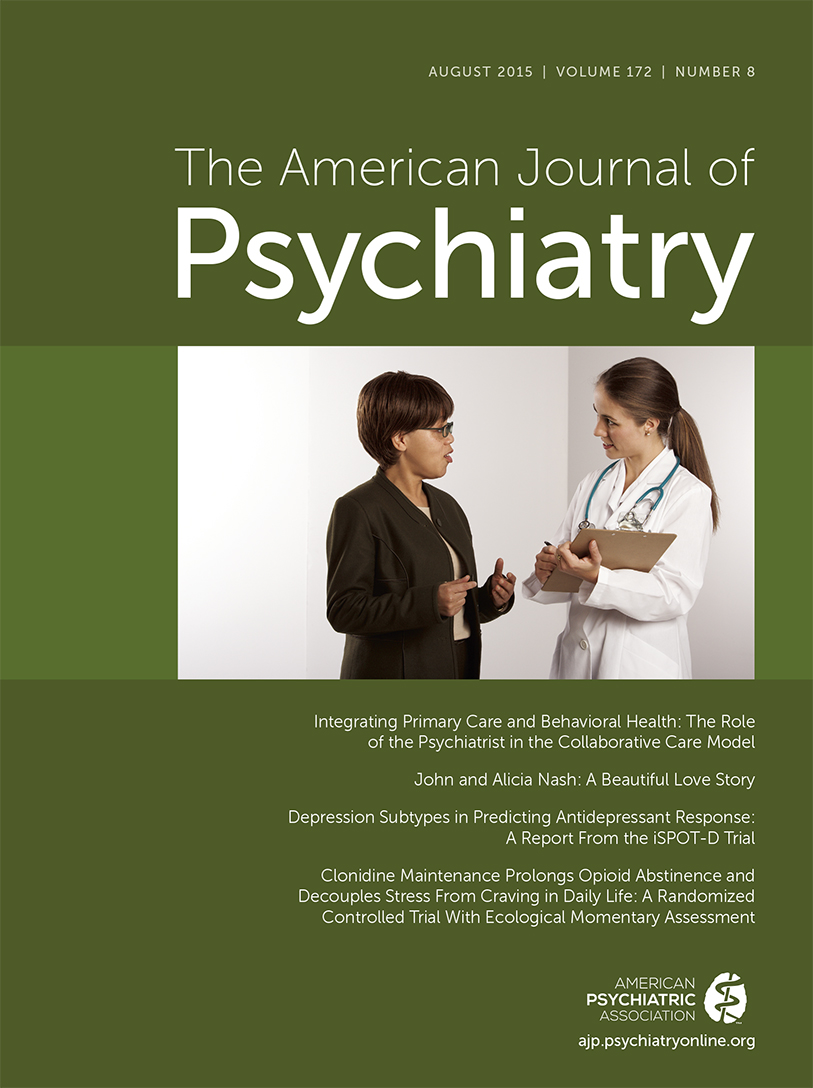

The attending psychiatrist and Dr. A. then saw the patient together. The patient was polite but subdued. She appeared tired and did not make direct eye contact. The attending sat across from the patient while Dr. A completed her electronic charting. Initially, the patient reported many of the same symptoms summarized in Dr. A’s presentation, but when asked about how her irritability was affecting her relationships at home, her eyes began to well up. Looking at the floor, she described her frustration with her toddler’s refusal to listen, her resentment toward her husband for being so unavailable, and her anger at herself for not being a better mother. Gently prompted by the attending, she acknowledged her shame about her feelings toward her son: “I love my little boy but he just doesn’t stop screaming. I’m so tired all the time—I never get a minute for myself. At times it feels like he’s sucking the life out of me. I feel so guilty that I even think such things.” She also acknowledged her fears that her own depression and anxiety had caused her son’s behavior. She wondered if her recent miscarriage was a sign that she was unable to handle more than one child and worried that taking sertraline could cause her to have another miscarriage.

Throughout this exchange, Dr. A continued to type with her back to the patient, writing up her assessment and plan so that the note could be completed by the end of the encounter. When it came time to discuss treatment, Dr. A turned back to the patient and appeared surprised to see her in so much distress. She watched as the attending discussed the treatment plan, which consisted not only of a medication recommendation but also referral to parenting support resources, a request that the patient bring in her husband to the next visit, and an appointment to follow up in 1 week rather than in 1 month.

After the patient left, Dr. A acknowledged that she had been so focused on completing the electronic chart that she had missed the patient’s emotion, leading her to significantly underestimate the severity of the patient’s distress. Abashed, Dr. A admitted, “I guess this wasn’t such a straightforward case after all.”

Electronic health records were meant to facilitate comprehensive evaluations and treatment planning, but the presence of a computer in the consultation room may have the opposite effect. The traditional office arrangement of comfortable chairs and couches naturally lends itself to making eye contact, observing the patient’s appearance and body language, and noticing subtleties in the patient’s affect. A computer divides the psychiatrist’s attention, drawing focus away from the patient. For a new psychiatrist, the computer template may serve as an anchor—a way to feel in control of the interview, a way not to miss important questions—but it also creates a barrier against the patient’s pain and suffering. There is a difference between writing down the patient’s words and hearing the patient’s words. Rather than being forced to see a patient in pain and grappling with overwhelming affect, the resident can look at the computer screen, check the appropriate boxes, and believe that she has done her job. But asking questions using a computer template creates an atmosphere in which the patient may not feel comfortable expressing her more shameful thoughts and feelings, knowing that they are being immediately typed into the record. Even when the patient expresses emotion or achieves insight, typing may limit the psychiatrist’s ability to empathize, understand, and connect.

We are faced with a clinical and educational challenge. Documentation takes time, and not writing notes until after an encounter adds minutes or even hours at the end of the day. Note-taking during clinical encounters has always been a difficult skill to learn. Even for millennials, for whom constant attention to a screen is a normal part of life, electronic charting increases the difficulty of note-taking, particularly in offices where the placement of the computer screen demands that the clinician look away from the patient. How and when the psychiatrist pauses to take a note, whether on paper or on a computer, requires careful thought and training.

Turning our backs on our patients is never acceptable. Our job is to listen, to observe, and to notice things that others might not. Creating a safe, welcoming space in which patients can express their most private thoughts and feelings enables us to capture the important details that form the basis of a comprehensive and meaningful assessment. In the words of William Osler, “Listen to your patient, he is telling you the diagnosis.”