Mixed states, characterized by concurrent manic and depressive symptoms, were described as early as ancient Greece, with the modern concept emerging through the late 19th-century writings of Emil Kraepelin (

1). More recently, DSM-IV operationalized the “mixed episode,” requiring full criteria for a depressive and manic episode to be met simultaneously. However, many argued that subsyndromal mixed states, which fall outside the strictly defined DSM-IV mixed episode, are common, may portend worse outcomes than pure depression or mania, and warrant classification as distinct clinical states (

2–

5). Recognizing the importance of subsyndromal mixed presentations, DSM-5 replaced the mixed episode with the “mixed features” specifier, defined by the presence of at least three nonoverlapping opposite-pole symptoms in the context of a syndromal depressive, hypomanic, or manic episode.

There has been growing interest in the phenomenology and clinical implications of the opposing mixed state—that is, manic or hypomanic symptoms during a depressive episode. Mixed depression, variably defined, has been identified in 21%−76% of depressed patients (

2,

3,

6–

10) and has been associated with such adverse clinical outcomes as suicide attempt history (

2,

3,

9), younger onset age (

2,

6,

9), and longer episode duration (

3,

9). The present study replicates the methodology of our previous work (

5) and assesses the prevalence and correlations of depression with concurrent subthreshold hypomanic symptoms in 907 prospectively followed patients with well-characterized bipolar disorders. In addition, the prevalence and correlations of DSM-5-defined major depressive episodes with mixed features are examined in the same cohort.

Method

Details of the methods and procedures used in the Stanley Bipolar Network have been described elsewhere (

11). All patients provided written informed consent through procedures approved by their individual institutions before entering the Stanley Bipolar Network study.

Sample

A total of 907 patients volunteered for a naturalistic follow-up study conducted from 1995 to 2002 involving prospective assessment of clinical state and medication use. Patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type were included. The Stanley Bipolar Network also enrolled patients in various embedded clinical trials, and patients could transfer from clinical trials to the naturalistic follow-up study (

11,

12). Included in this report are those enrolled only in the naturalistic follow-up study; patients who participated in other trials were excluded in the event that specific inclusion or exclusion criteria would bias the likelihood of co-occurrence of symptoms.

Procedures

All patients underwent diagnostic evaluation with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Patients were seen monthly on average, with medication changes made as needed. At each visit, mania and depression symptoms were assessed prospectively with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (

13) and the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Clinician-Rated Version (IDS-C) (

14,

15). Across four U.S. and three non-U.S. sites, interrater reliability was regularly assessed, and rater training was reinforced as needed to maintain consistent performance (kappa values were 0.7 for the YMRS and 0.85 for the IDS-C). The analyses include all naturalistic follow-up study visits at which both the YMRS and IDS-C assessments were completed. Less than 0.5% of total visits were excluded due to missing one scale; no visits were missing both symptom scales.

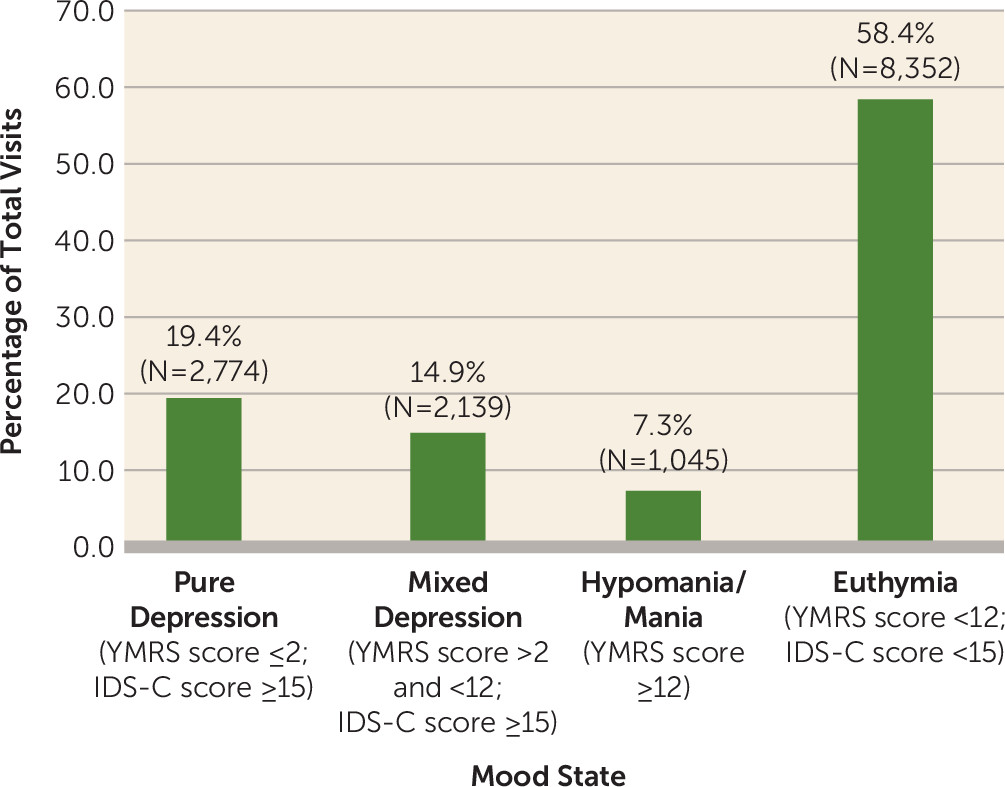

Same-visit scores on the IDS-C and YMRS were used to define mixed depression. For the purposes of this analysis, definitions for depression, hypomania and mania, and mixed depression were intentionally inclusive. On the IDS-C, mild depression is indicated by a score of 15–24, moderate depression by a score of 25–34 (symptoms presumably adequate to meet DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode), and severe depression by a score ≥35. A YMRS score ≥12 is considered reflective of at least mild hypomania (symptoms presumably adequate to meet DSM-IV criteria for hypomania). Importantly, IDS-C and YMRS scores serve as measures of overall symptom severity but not of symptom pervasiveness or duration, and in that sense the scores provide only indirect approximations of the presence or absence of DSM-defined syndromal mood episodes. In the present analysis, we defined depression as the presence of an IDS-C score ≥15 and a YMRS score <12; hypomania or mania as a YMRS score ≥12; and euthymia as an IDS-C score <15 and a YMRS score <12. Depression was subdivided into pure (IDS-C score ≥15, YMRS score ≤2) and mixed (IDS-C score ≥15, YMRS score >2 and <12) depression.

In addition, we applied DSM-5 criteria for a major depressive episode with mixed features to our sample, to examine a DSM-5-based construct of mixed depression. To this end, visits with depression were defined as described above (IDS-C score ≥15, YMRS score <12). The DSM-5 “with mixed features” criteria were met if at least three YMRS items were scored ≥1 during depressed visits. Individual YMRS items that directly overlapped with IDS-C items or were not reflective of DSM-5 criteria A or B symptoms for mania were not counted toward this definition, to maintain consistency with DSM-5 criteria. Therefore, three YMRS items were excluded from our DSM-5-based definition, with one (item 5, “irritability”) considered to be overlapping with IDS-C items and two (item 10, “appearance,” and item 11, “insight”) failing to map onto DSM-5-based symptoms. YMRS item 2 (“increased motor activity/energy”) was permitted as a nonoverlapping mood elevation symptom based on the opinion that it primarily assesses elevated energy, a feature specific to mood elevation. This item was considered distinct from IDS-C item 24 (“psychomotor agitation”), which assesses non-goal-directed restlessness or agitation (a potential feature of both depression and mood elevation). An additional DSM-5-based definition requiring only two YMRS items scored ≥1 was also examined. Exploratory analyses were also performed that required an IDS-C score ≥25 to align more closely with syndromal depression.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS, version 21 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y.). The primary analyses were of repeated measures, using generalized estimating equations to investigate the likelihood of experiencing subthreshold hypomania (i.e., mixed symptoms) during visits with depression. All models included a dichotomized indicator of subthreshold hypomania (YMRS score >2 and <12) as the dependent variable, a dichotomized indicator of depression (IDS-C score ≥15) as the independent variable, and study week as a linear covariate, to control for the effect of time on mood symptom severity. The predictor variables of interest for this study were gender, given our previously demonstrated relationship between gender and mixed hypomania (

5), and bipolar subtype, given associations between bipolar II diagnosis and mixed depression in some (

2,

8), but not all (

7), previous studies. Analogous methods were used to assess gender and diagnosis effects on DSM-5-defined mixed depression.

To examine the profiles of individual YMRS and IDS-C item scores as functions of mixed or pure depression status, we performed two separate multivariate analyses of covariance, with the individual YMRS and IDS-C item scores as dependent variables in each model, respectively, and with mixed or pure depression status as the dichotomous independent variable.

Discussion

In a sample of 907 patients with bipolar disorder followed naturalistically across 14,310 visits, we found that 64.4% of patients experienced at least one visit with mixed depression, defined broadly as the presence of subthreshold hypomania (YMRS score >2 and <12) concurrent with at least mild depression (IDS-C score ≥15). Mixed depression defined as such was present during 14.9% of all visits over the 7-year study period. Narrower definitions, based on DSM-5 criteria for depression with mixed features, yielded lower prevalence rates of mixed depression, ranging from 2.6% to 10.8%.

Across our mixed depression definitions, diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder did not predict the likelihood of subthreshold hypomania during visits with depression. This finding aligns with our previous study examining mixed hypomania, where we found no effect of bipolar subtype on the likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms during visits with hypomania (

5). Other studies of mixed depression reported either increased bipolar I disorder prevalence (

16), increased bipolar II disorder prevalence (

2,

8), or no difference in bipolar I or bipolar II prevalence (

3) in patients with mixed depression compared with pure depression. Thus, bipolar subtype may not be a consistently robust predictor of mixed depression.

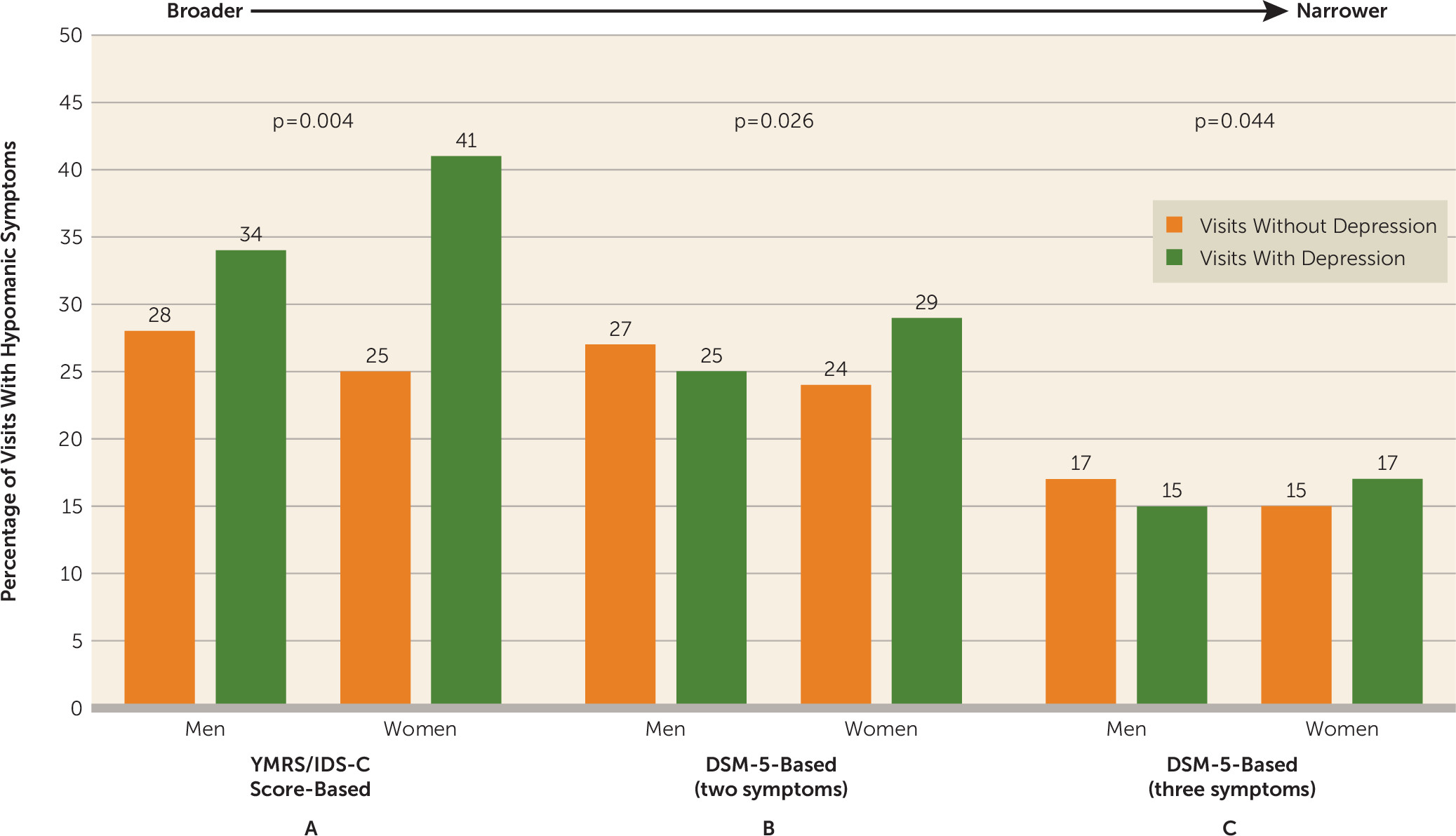

In contrast, we found that gender was a significant predictor of mixed depression across definitions, with women being more likely than men to experience subthreshold hypomania during depression visits. The effect of gender on mixed depression was similar to that demonstrated in our mixed hypomania study, in which women were more likely than men to experience depressive symptoms during hypomania visits (

5). Thus, in our cohort of patients with bipolar disorder, women were more likely than men to experience mixed features in general. While some previous studies also found mixed depression to be more common in females (

17,

18), many found no gender effect (

3,

16,

19,

20), and one study found that mixed depression occurred more frequently in males (

2). Our association of female gender with mixed depression may conflict with the expectation that certain mood elevation symptoms (e.g., irritability, agitation, and impulsivity) are more commonly endorsed by male patients during depressed and/or mixed states (

5,

21). On the other hand, some have argued that such conventionally “male” symptoms may actually occur with similar or greater prevalence among female patients with depression (

22). Further studies are clearly warranted to evaluate the effect of gender on mixed symptom presentations in bipolar disorder.

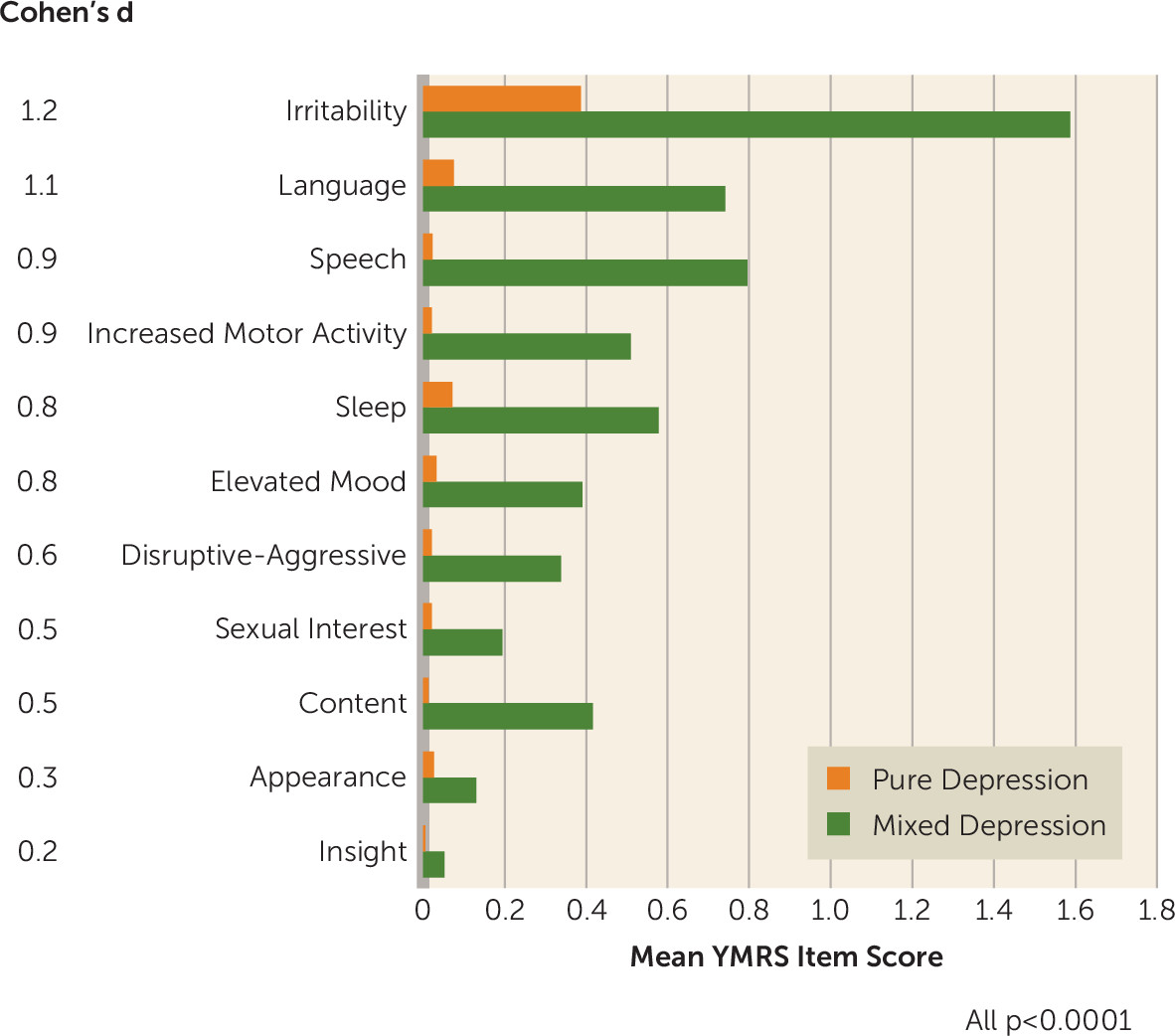

Visits with mixed depression compared with visits with pure depression were characterized by higher scores on all individual YMRS items, and the largest effect sizes were seen for irritability, language–thought disorder, speech, and increased motor activity. Interestingly, the latter three YMRS items were predictive of antidepressant treatment-emergent mania in an earlier Stanley Bipolar Network report (

23). The present findings suggest that the presence of mixed symptoms during depression visits may signal heightened risk for antidepressant-induced mania, warranting particular caution in clinical decision making. In contrast, mixed depression status did not robustly affect IDS-C item scores, raising the possibility that depressive-pole symptomatology may not differ substantially across pure and mixed depression states.

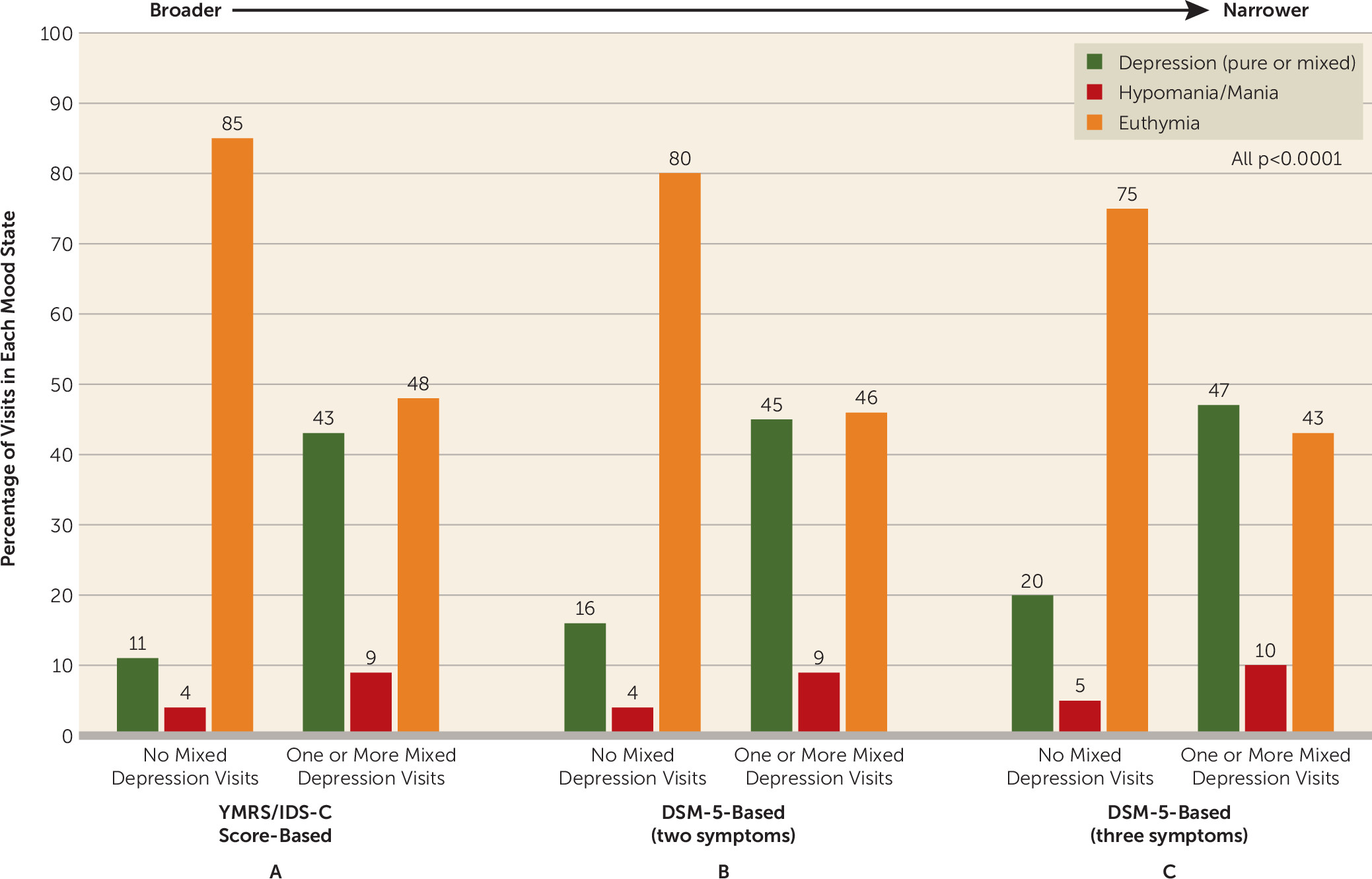

We found that patients with at least one mixed depression visit, compared with those with no mixed depression visits, were more likely to have at least one mixed hypomania visit. Thus, certain patients may be predisposed to experiencing mixed features in general, a concept supported by previous prospective analyses (

24–

26). We also found that patients with at least one mixed depression visit, compared with patients without any mixed depression visits, were more likely to experience visits with depression and/or mood elevation and were less likely to experience visits with euthymia. This finding is consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting that mixed depression may be a predictor of more severe bipolar illness course (

2–

4,

19,

20,

27). The robust association with longitudinal symptom severity is noteworthy given that most patients with mixed depression in our cohort experienced only a few (≤3) such visits across their total follow-up duration. Thus, even sporadic presentations of mixed depression within individual patients may portend adverse outcomes.

Applying a strict three-symptom DSM-5-based definition to our data set resulted in a low prevalence rate of mixed depression visits but also yielded findings similar to those seen under our broader definitions of mixed depression. Thus, our results raise the possibility that relaxing the diagnostic criteria for the mixed features specifier (for example, requiring two rather than three mood elevation symptoms) may yield greater sensitivity for identifying patients with mixed depression. Indeed, a recent International Society for Bipolar Disorders task force report indicated that the illness characteristics associated with mixed depression states (e.g., increased prevalence of comorbidities, adverse treatment outcomes, and suicidality) appear stable across a range of diagnostic criteria for mixed states, with such clinical correlates becoming evident in the presence of as few as two nonoverlapping, opposite-pole symptoms (

28).

Similar questions have been raised regarding the validity of excluding “overlapping” symptoms from the DSM-5 mixed features criteria. Although the implications of permitting or excluding overlapping symptoms were not explicitly assessed in the present report, we found that irritability and increased motor activity were among the most prominent symptoms during mixed depression visits. Recently published data from a multisite, cross-sectional study of 2,811 depressed patients also demonstrated the predominance of irritability and psychomotor agitation in patients with mixed depression, even when strict DSM-5 criteria were applied, leading the authors to suggest that these symptoms may in fact be core features of mixed depression (

9). In contrast, others have argued that symptoms like irritability and agitation, although highly prevalent during mixed states, are also robustly linked with conditions that frequently co-occur with mixed states (e.g., anxiety, substance use, and personality disorders) and therefore lack specificity for diagnosing mixed depression (

29,

30). More research is needed to understand the complex role of overlapping symptoms in the construct of mixed depression and to consider whether including these symptoms as gateway criteria in the future will increase clinical utility.

Our study has several important strengths, including the large sample of well-characterized patients with bipolar disorder; a prospective study design; broad inclusion criteria, which optimize generalizability; and the use of standardized, validated rating scales for clinical assessment. However, the study also has noteworthy limitations, including our reliance on observational rather than controlled data, introducing clinical and demographic heterogeneity. Because of variable visit frequencies across participants, it was not possible to differentiate whether symptoms present at visits represented new or persistent mood episodes, thus limiting our interpretation of longitudinal trajectories of mixed features. Finally, our reliance on mood symptom rating scales limited our ability to examine a strictly DSM-5-based definition of mixed depression.

In summary, among 907 bipolar disorder patients in 14,310 visits, depressive symptoms were common, and subthreshold hypomania occurred in almost half of all visits with depression. We demonstrated that women were more likely than men to experience hypomanic symptoms concurrently with depression across a range of diagnostic criteria for mixed depression. The presence of mixed depression appears to be a marker of vulnerability to mixed depression features in general and may portend a more symptomatic course of illness over time. The stability of our mixed depression construct across a range of definitions supports the possibility that broader diagnostic criteria for mixed depression may improve sensitivity while preserving clinical meaningfulness.