Serious antisocial behavior is a key feature of the psychiatric diagnoses of conduct disorder in youths and antisocial personality disorder in adults. Given their high cost, serious antisocial behaviors, such as aggression, violence, and rule breaking, are a major public health concern. For example, a recent study found that each adolescent diagnosed with conduct disorder cost society $14,000 more per year than other high-risk adolescents (

1). With a lifetime prevalence of 10% for conduct disorder (

2), the financial implications of antisocial behavior are staggering. Additionally, these behaviors have broader, immeasurable occupational, health, social, and emotional costs for perpetrators, victims, and their families. Decades of research have shown that the most severe trajectories of antisocial behavior start in early childhood (

3–

5). Thus, prevention programs have begun to target children at younger ages, when behavior may be more malleable and life course trajectories can be more easily modified (

6). However, the effectiveness of interventions remains limited, and the marked heterogeneity of individuals with antisocial behavior may contribute to this problem (

7). If the etiologies of specific forms of antisocial behavior can be established, then more effective targeted, personalized interventions can be developed.

To address heterogeneity in early-onset antisocial behavior, a specifier was added to the diagnosis of conduct disorder in DSM-5 to assess the presence of callous-unemotional traits (“limited prosocial emotions”). Callous-unemotional traits, characterized by low empathy, callousness, and low interpersonal emotions, identify youths with severe, chronic, and stable antisocial behavior (

8). Studies demonstrating distinct neural correlates and higher heritability of antisocial behavior in the presence of callous-unemotional traits suggest that antisocial behavior with and without callous-unemotional traits has different etiological pathways (

9–

11). However, as most research on callous-unemotional traits has focused on late childhood and adolescence, we know little about the developmental origins of callous-unemotional traits.

To address this gap, researchers have begun studying callous-unemotional-like

behaviors (e.g., lack of guilt, low fear) in the toddler and preschool periods and found that these behaviors identify children with a more severe and homogeneous trajectory of early behavior problems (

12). Similar to callous-unemotional traits measured in adolescence, early callous-unemotional behaviors are associated with lower levels of guilt, empathy, and moral regulation and higher levels of proactive aggression (

13). These behaviors, measured as early as age 3, predict more severe antisocial behavior (

13) and callous-unemotional traits at age 10, over and above other preschool antisocial behaviors (

14). Thus, early callous-unemotional behaviors predict more severe antisocial behavior trajectories and the development of callous-unemotional traits in later childhood, and they may help identify those in most need for early intervention (

14). However, we know little about the etiology of these early emerging behaviors.

Twin studies suggest that callous-unemotional traits in middle childhood are highly heritable (heritability estimates range from 0.45 to 0.67) (

9). However, twin studies of callous-unemotional traits have not identified specific heritable parental traits that put children at greater risk for callous-unemotional behaviors (although see reference

15). An important parental behavior that may signal genetic risk for callous-unemotional behaviors is biological parents’ antisocial behavior. Specifically, history of severe antisocial behavior may be indicative of heritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors because of the overlap between later callous-unemotional traits, psychopathy, and severe antisocial behavior (

8). Although establishing these heritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors is critical for understanding the development of callous-unemotional behaviors and severe antisocial behavior more broadly, children typically receive both genes and rearing environments (e.g., parenting) from their parents. Such gene-environment correlations, present in most observational study designs, make it difficult to differentiate genetic from environmental contributions. An adoption design, particularly one in which children are adopted soon after birth, allows for an examination of heritable and nonheritable pathways because biological parents do not provide the rearing environment. Thus, the first goal of the present study was to use an adoption design to examine inherited pathways from biological mothers’ antisocial behavior to early child callous-unemotional behaviors.

Whereas much research on callous-unemotional traits in youths has focused on biological correlates of callous-unemotional traits (

10), a growing literature has shown that dimensions of parenting, including harshness and warmth, are important in the development of callous-unemotional traits (

16), and even callous-unemotional behaviors as early as age 2 (

17). Recent studies suggest that specific aspects of positive parenting, including warmth and positive reinforcement, are particularly important for protecting against the development of callous-unemotional behaviors (

18) by contingently reinforcing positive child behavior and nurturing a warm parent-child relationship (

16,

19). Studies that examine how positive parenting behaviors are related to the development of callous-unemotional behaviors are critical to translational work, because these aspects of parenting are a major malleable target for interventions for antisocial behavior.

However, most typical studies of biological parents rearing their own children cannot rule out the possibility that associations between parenting and child behavior are attributable to genes that influence both parenting and child behavior (

15,

20), a notion supported by a monozygotic twin differences study finding little evidence for harsh parenting as a nonshared environmental predictor of callous-unemotional behaviors (

15). Thus, genetically informed research is needed to examine whether positive parenting directly contributes to the development of callous-unemotional behaviors beyond shared genes. Recently, we showed the first evidence for a nonheritable parenting pathway in the present sample (

14) by demonstrating a negative correlation between adoptive parents’ positive parenting and children’s callous-unemotional behaviors when children were 27 months old. Although this adoption design eliminated passive gene-environment correlation, the findings were cross-sectional. Thus, these results could reflect the impact of evocative gene-environment correlation in which child callous-unemotional behaviors evoke lower parental warmth. Therefore, research is needed to test whether dimensions of positive parenting predict lower levels of callous-unemotional behaviors prospectively, while controlling for earlier callous-unemotional behaviors and their potential evocative effects, as well as heritable pathways from birth parents. Thus, our second aim was to examine prospective links between positive parenting and callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood within an adoption study.

Finally, because parenting-focused interventions often aim to reroute the trajectory of children with early forms of antisocial behavior by increasing positive parenting (

21,

22), an important question is whether positive parenting can protect against the emergence of callous-unemotional behaviors in the context of high genetic risk for these behaviors. From the perspective of translational research, it is not sufficient to show that positive parenting predicts lower levels of callous-unemotional behaviors over time, but that positive parenting protects youths with the highest genetic risk from developing or maintaining high levels of callous-unemotional behaviors (

20). Thus, our third aim was to examine whether the heritable risk posed by antisocial biological mothers could be reduced by adoptive mothers’ positive parenting behaviors.

In the present study, we tested novel heritable and nonheritable pathways to preschool callous-unemotional behaviors in a sample of 561 children and their families from the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS), a landmark prospective adoption study with multi-informant measures of biological and adoptive parents as well as longitudinal measures of early child behavior. The present study builds on a recent study (

14) in which we established the factor structure of a measure of early callous-unemotional behaviors in the EGDS, demonstrated that parent reports of callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months predicted teacher-reported antisocial behavior at age 7 over and above other dimensions of early antisocial behavior (i.e., oppositional and attention-deficit behaviors), and found a negative cross-sectional correlation between children’s callous-unemotional behaviors and adoptive parents’ positive parenting when children were 27 months old. To further this work and examine heritable, nonheritable, and gene-environment interaction pathways prospectively, we examined whether biological mothers’ self-reports of severe antisocial behavior predicted greater adoptive parent reports of child callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months after accounting for other forms of early behavior problems (oppositional and attention-deficit behaviors). Moreover, we incorporated a longitudinal component by testing whether observations of adoptive mothers’ positive reinforcement when children were 18 months old predicted lower levels of callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months. Finally, we tested whether parenting moderated inherited influences on callous-unemotional behaviors by examining whether the link between biological parent antisocial behavior and child callous-unemotional behaviors was significantly attenuated for children whose adoptive mothers demonstrated high levels of positive reinforcement.

Method

Sample

This study used data from the EGDS, a linked set of participants including 561 adopted children (42.8% of them female), their adoptive parents (567 adoptive mothers, 552 adoptive fathers, including 41 same-sex parent families), and their biological mothers (N=554) and fathers (N=208). Children were adopted within a few days after birth (median=2 days; range=0–91 days), limiting the extent to which biological parents influenced their child via postnatal environmental effects (

23). The children of the sample are relatively racially and ethnically diverse (55.6% Caucasian, 19.3% multiracial, 13% African-American, 10.9% Latino). The sample was recruited in two cohorts. Further information about the sample, including recruitment, consent, and procedures, is available elsewhere (

23,

24).

Measures

Dimensions of early externalizing.

We assessed dimensions of early externalizing behaviors at 27 months using adoptive mother report on items from the preschool Child Behavior Checklist (

25). Specifically, we used a three-factor model with 17 items that form separable callous-unemotional, oppositional, and attention-deficit behavior scales. This factor structure has been replicated in five independent samples and was the focus of our previous work in EGDS (

14) (see the Supplemental Methods section in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article).

Biological mother antisocial behavior.

We assessed biological mother antisocial behavior when adoptive children were 3–6 months old using 47 items from the self-reported computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule (

26,

27). To assess a phenotype closely related to callous-unemotional traits, we also created a measure of “severe antisocial behavior” using the 10 most severe antisocial/illegal items in this measure (see the Supplemental Methods section).

Observed adoptive mother positive reinforcement.

Adoptive mothers’ use of positive reinforcement was observed in the home when children were 18 months old via microsocial coding of a 3-minute cleanup task. Videos of this interaction were coded using the Child Free Play and Compliance Task Coding Manual (K. Pears and M. Ayers, unpublished manual, 2005). Mothers’ utterances containing positive reinforcement (e.g., “good job,” “thanks for picking that up”) were summed, leading to a proportion of positive reinforcement based on the length of the task. Fifteen percent of the videos were coded by two independent coders; average intercoder agreement was 88% (overall kappa=0.71). This variable was coded only for cohort 1 (N=334) and was treated as planned “missing” in all models. Results were identical when we examined only cohort 1 (see Table S1 in the online data supplement).

Covariates.

Consistent with previous publications from EGDS, we included child gender, adoption openness (level of contact between biological and adoptive families) (

28), and an index of perinatal risk (

29) as covariates in all models.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were carried out in Mplus, version 7.2, using mean and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation (

30) (see the Supplemental Methods section). We modeled callous-unemotional behaviors within a three-factor framework that accounted for the overlap of callous-unemotional with attention-deficit and oppositional behaviors (

14). For our first aim, we used structural equation modeling to assess the unique effect of biological mother antisocial behavior on callous-unemotional, oppositional, and attention-deficit behaviors while controlling for gender, adoption openness, and perinatal complications. For our second aim, we examined whether adoptive mother positive reinforcement predicted callous-unemotional behaviors by adding this variable to the previous model. By testing this stringent model, we examined whether positive reinforcement contributed to callous-unemotional behaviors over and above the biological mother’s inherited contributions. In a second step, we included callous-unemotional behaviors at 18 months to ensure that any effects were not the result of evocative effects of children’s higher levels of earlier callous-unemotional behaviors on parenting. For our third aim, we tested an interaction in which an interaction term (biological mother antisocial behavior by adoptive mother positive reinforcement) was added to the model (see

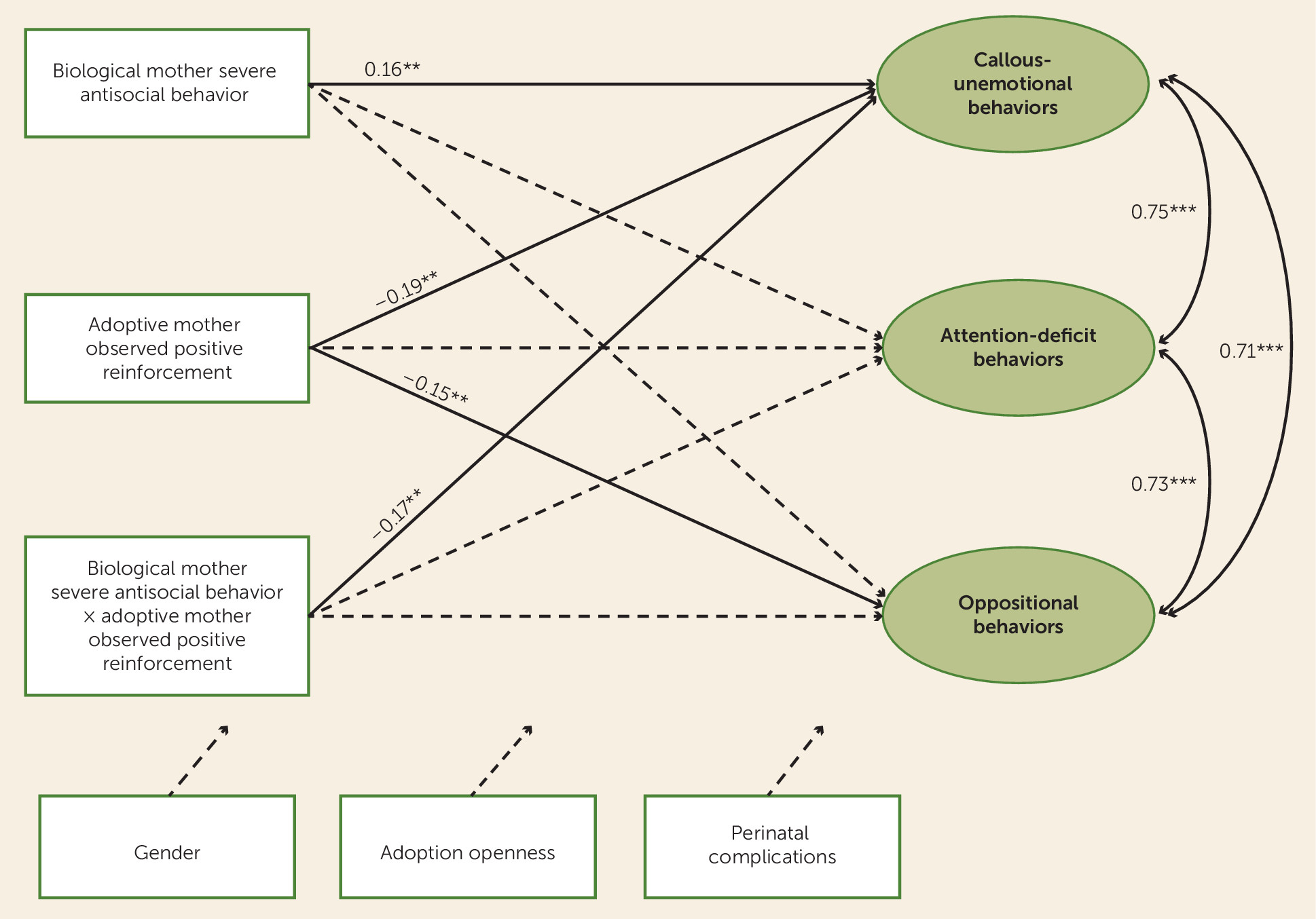

Figure 1).

Results

Does Biological Mother Antisocial Behavior Predict Early Child Callous-Unemotional Behaviors?

Evidence was found for heritable risk in a main effect of biological mother severe antisocial behavior on child callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months (B=0.13, SE=0.04, β=0.16, p<0.01). This effect took into account overlap with attention-deficit and oppositional behaviors, as well as the effects of child gender, adoption openness, and perinatal complications. Effects were unique to callous-unemotional behaviors: biological mother antisocial behavior did not predict attention-deficit or oppositional behavior.

Does Adoptive Mother Positive Reinforcement Predict Early Child Callous-Unemotional Behaviors?

When observed adoptive mother positive reinforcement was added into the previous model, biological mother antisocial behavior continued to predict child callous-unemotional behaviors, while higher levels of observed adoptive mother positive reinforcement at 18 months uniquely predicted lower levels of child callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months (B=−2.38, SE=0.94, β=−0.19, p<0.001). This adoptive mother parenting effect remained when we controlled for evocative effect of callous-unemotional behaviors at 18 months (B=−3.00, SE=1.2, β=−0.19, p<0.01).

Does Adoptive Mother Positive Reinforcement Buffer Heritable Risk For Callous-Unemotional Behaviors?

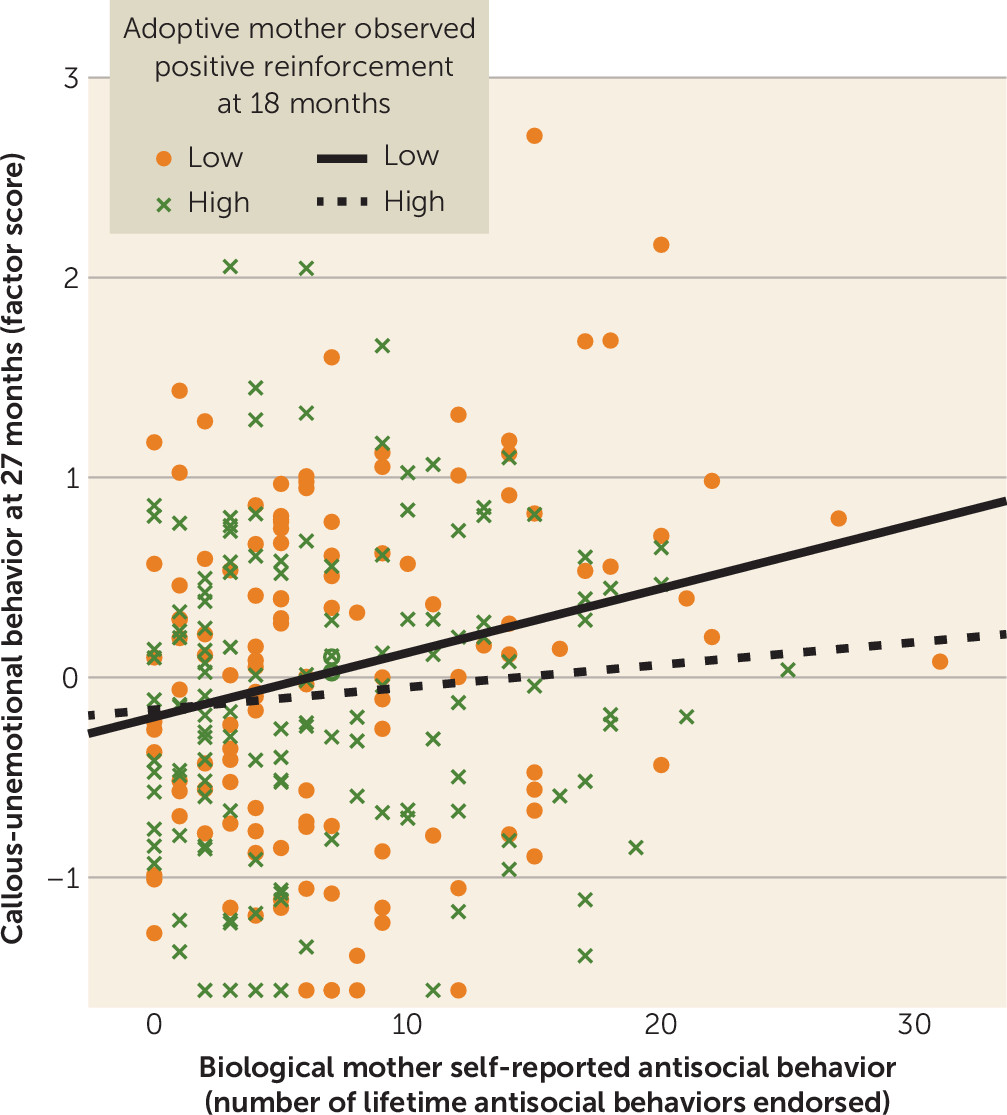

Finally, an interaction was evident between adoptive mother observed positive reinforcement and biological mother antisocial behavior (see

Table 1 and

Figure 1). This interaction (

Figure 2) showed that at low, but not high, levels of observed positive reinforcement of adoptive mothers, biological mother antisocial behavior predicted child callous-unemotional behaviors (low: B=0.17, SE=0.08, β=0.24, p<0.05; high: B=0.01, SE=0.01, β=0.01, p>0.90).

Discussion

We report the first evidence of a specific gene-environment interaction that shapes heritable and nonheritable pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviors with a novel genetically informed design that allows for stronger conclusions than past studies. We found a specific heritable pathway to callous-unemotional behaviors, as biological mother antisocial behavior predicted child callous-unemotional behaviors in the late toddler period. We also demonstrated that parenting prospectively predicts early callous-unemotional behaviors even when parents are not genetically related to the child. Additionally, we found an important gene-environment interaction whereby more positively reinforcing mothers buffered inherited risk for early callous-unemotional behaviors. In contrast, the combination of both heritable and nonheritable risk was related to the highest levels of callous-unemotional behaviors. These findings highlight both heritable and nonheritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors, but they also emphasize that ultimately, callous-unemotional behaviors are the product of an interaction between pathways. Evidence for the importance of parenting in the face of inherited risk is critical for parenting-focused intervention efforts, as the results emphasize that positive reinforcement from parents can help buffer existing genetic risk, even in children at high risk for persistent antisocial behavior. This message is particularly important when discussing a “highly heritable” set of behaviors, because these findings emphasize that heritability is not destiny. Even children with risk for later callous-unemotional behaviors can have their behavior sculpted by high levels of positive reinforcement.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, that identifies a specific heritable pathway to early callous-unemotional behaviors. This pathway was particularly strong when we focused on the most serious maternal antisocial behavior, implying that serious antisocial behavior is a more precise phenotype for understanding heritable risk for early callous-unemotional behaviors. Our findings provide a direct test of one possible heritable pathway suggested by recent findings from Dadds and colleagues (

31), who found that paternal psychopathic fearlessness was related to low child eye contact in early childhood during an interaction task. As poor eye contact has been studied as an endophenotype for callous-unemotional traits, this research has been interpreted as supporting a possible genetic link from parental psychopathic traits to mechanisms involved in the development of child callous-unemotional traits (

32). Our results add a direct test of a heritable pathway by showing that biological parents’ (in this case mothers’) severe antisocial behavior predicts early callous-unemotional behaviors, even when that parent is not rearing the child. Given theoretical links between later callous-unemotional traits and interpersonal deficits found in adult psychopathy, it would have been ideal to examine whether biological parent psychopathic traits were related to early callous-unemotional behaviors. Unfortunately, this construct has not been measured in the EGDS. However, the more serious antisocial behavior items we did measure may tap a phenotype more closely related to callous-unemotional traits in the parent (

8,

33). Future work could elucidate whether specific traits associated with psychopathy (e.g., fearlessness) mediate heritable pathways between serious parental antisocial behavior and child callous-unemotional behaviors.

Beyond heritable pathways, our results provide convincing evidence that parenting is important in the development of callous-unemotional behaviors. Through an adoption design and by examining prospective relationships between parental positive reinforcement and child callous-unemotional behaviors, we exclude some important gene-environment correlation confounders present in previous research (

16). We measured these processes during a critical developmental period: Parenting during the toddler years becomes increasingly difficult as toddlers gain more mobility and autonomy without concomitant self-regulation skills. Thus, parenting during these years is critical to promoting positive behavior trajectories (

6). Empathy, prosocial behavior, and guilt also develop during this period (

34), making it an important time in the pathway toward the development of callous-unemotional traits and serious antisocial behavior (

14). Moreover, as early callous-unemotional behaviors may also evoke harsher parenting (

19), preventing callous-unemotional behaviors early in life may attenuate the development of transactional, cascading coercive cycles of behavior between parents and children that contribute to serious antisocial behavior (

35).

Our findings are striking in demonstrating direct effects of positive reinforcement on callous-unemotional behaviors even in the absence of shared inherited vulnerability and evocative effects. Positive reinforcement may be particularly important for preventing callous-unemotional behaviors, as a mutually warm relationship can set the foundation for the development of empathic concern (

19,

36). Our findings augment studies in early childhood demonstrating that reduced quality of positive affective interactions between parent and child, including lower eye contact, lower observed dyadic warmth, and lower maternal sensitivity, appears to be a risk factor for callous-unemotional behaviors (

16,

31,

37). Thus, not surprisingly, high levels of positive reinforcement by adoptive mothers were effective at buffering inherited risk, attenuating the effect of biological mother antisocial behavior on later callous-unemotional behaviors. This interaction emphasizes the malleability of early callous-unemotional behaviors and suggests that positive reinforcement should be emphasized in interventions for early callous-unemotional behaviors (

18).

Although our study had several strengths, including an innovative adoption design with a large number of children adopted soon after birth, observational measures of parenting, and assessment of callous-unemotional behaviors during a critical developmental period, it also has a few limitations. We did not measure psychopathy or related constructs in biological parents. However, our measure of severe antisocial behavior uniquely predicted callous-unemotional behaviors, and not other dimensions of antisocial behavior, suggesting specificity in this heritable pathway. Second, although there was variability in early child callous-unemotional behaviors, this community sample contained few children already showing clinical levels of antisocial behavior. Third, our sample of adopted children and participating biological families and adoptive families may not represent the general population: Adoptive families had greater resources (i.e., family income >$100,000 per year) and fewer risk factors, while biological families had lower resources and more risk factors for antisocial behavior than families in the general population. In translating these findings to clinical settings, it is important to consider the relatively high heritability estimates for callous-unemotional traits (

38) and our findings of heritable associations between parent antisocial behavior and child callous-unemotional behaviors. Thus, in a “typical” family, children with high levels of callous-unemotional behaviors, who are in the most need of positive parenting, are also more likely to have parents with greater genetic risk and more contextual risk factors for antisocial behavior (e.g., low income, high family stress), who may engage in harsher forms of parenting (

15). These parents also may be less likely to seek intervention services. Thus, our adoption findings show “what can be” in a natural experiment, but interventions must contend with the challenges of implementing parenting interventions in biological family contexts that may require more engagement and family support to implement sustained positive parenting change. Interventions that meet families in their communities, have regular contact with families, increase social support, and increase motivation for change may be more effective in engaging these families in which children have high heritable and nonheritable risk (

21). Finally, our analyses focused only on mothers because we were missing substantial data for biological and adoptive fathers on our variables (only 33% and 37% data for each, respectively). Thus, we may be underestimating heritable effects by exclusively examining biological mothers’ contributions and not probing the extent to which fathers contribute to pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors. Moreover, it should be noted that parenting was coded within only one EGDS cohort, although results were identical using only cohort 1 data (see Table S2 in the

online data supplement).

In sum, we found compelling evidence that severe maternal antisocial behavior increases risk for early callous-unemotional behaviors in offspring via genetic pathways. However, positive reinforcement from adoptive mothers was a nonheritable predictor of lower levels of callous-unemotional behaviors, and it buffered against heritable risk. These findings highlight a specific gene-environment interaction in the development of callous-unemotional behaviors and emphasize that positive parenting can reduce risk for early warning signs of future antisocial behavior. This conclusion emphasizes the importance of positive reinforcement in parenting-based interventions for callous-unemotional behaviors and provides a critical message for parents and others working with children with early antisocial behavior: Early callous-unemotional behaviors are heritable and can identify those at risk for continued antisocial behavior; however, these behaviors are malleable, and positive reinforcement from parents can alter these risky pathways.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the biological parents and adoptive families who participated in this study and the adoption agencies who helped with the recruitment of study participants. They also gratefully acknowledge Rand Conger, John Reid, Xiaojia Ge, and Laura Scaramella for their contributions to the larger project.