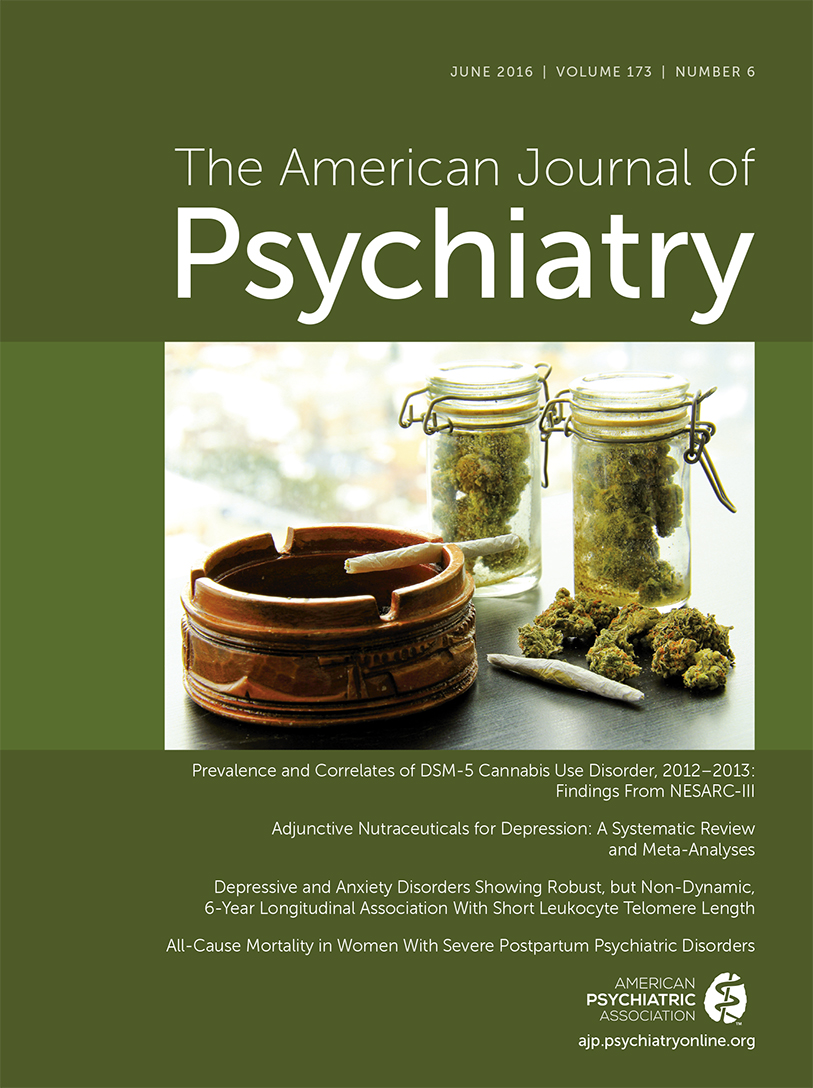

The study of cannabis use disorders has become urgent because of several factors: increasing cannabis legalization in multiple states and jurisdictions (

1), the high and increasing prevalence of cannabis use (

2), prospective evidence of the impact of cannabis use on future risk of psychiatric disorders (

3), and evidence for multiple deleterious effects of cannabis exposure (

4). It is against this backdrop of a rapidly changing legal landscape and emerging evidence of harms from cannabis use that we should consider Hasin and colleagues’ rigorous analysis of the prevalence, demographic characteristics, psychiatric comorbidity, disability, and treatment for DSM-5 cannabis use disorders in the U.S. adult population (

5). This study will go a long way toward helping psychiatrists and all clinicians to treat patients more effectively and participate more actively in policy discussions.

Going into this study, we knew that 12.5% of persons age 18 or older in the United States reported past-year use of cannabis in 2013 (

2). This prevalence is about 19% higher than the 10.5% found in 2002 (

2), an increase that was likely fueled, at least in part, by the inverse relationship between cannabis use and the perception of harmfulness (

6). This trend is problematic because cannabis use is associated with increased risk for a number of adverse cognitive, psychiatric, physical, and social effects, including comorbid mental disorders (

3,

4).

The increasing prevalence of cannabis use combined with the evolving definition of cannabis use disorder in the revised DSM-5 nomenclature warranted reassessment of cannabis epidemiology. For instance, changes in DSM-5 (compared with DSM-IV) included the addition of withdrawal as a recognized component of cannabis use disorder. DSM-5 also included universal changes for all substance use disorders, including cannabis use disorders. Of particular note, DSM-5 eliminated the DSM-IV abuse and dependence disorders in favor of a single, unified substance use disorder with severity determined by the number of criteria endorsed (

7).

Hasin and colleagues report findings from the landmark National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, which included psychiatric interview data from 36,309 persons age 18 or older in 2012–2013, to determine the rates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder and its correlates (

5). Cannabis use disorder was found to be prevalent, with a past-year rate of 2.5% and a lifetime rate of 6.3%. Rates were higher among men, Native Americans, unmarried persons, younger persons, and those with low incomes. Comorbidity was found to be common, with strong associations of cannabis use disorder with other substance use disorders, affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and personality disorders.

Factual information about cannabis use disorder is sorely needed, and the article by Hasin and colleagues is likely to become the standard reference on the topic. Particularly compelling is the information about demographic correlates and comorbidity. The demonstration of strong associations with other substance use disorders (related to tobacco, alcohol, and other illicit drugs) and other psychiatric disorders (personality, anxiety, and mood) is consistent with findings from previous studies based on DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV criteria, but the addition of information about how increasing severity of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder is reflected in the increasing strength of the associations with these comorbid psychiatric disorders is quite novel. Hasin and colleagues found that increasing DSM-5 cannabis use disorder severity was also associated with poorer functioning and stronger correlation with risk factors (

5). It appears that the severity subtypes implemented in DSM-5 are reliable predictors of such associations. These findings suggest that clinical problems associated with cannabis use disorder exist along a severity continuum, like the disorder itself.

The low rates of treatment documented by Hasin and colleagues are also noteworthy (

5). Only 13.7% of adults with a lifetime cannabis use disorder ever sought any type of treatment or intervention. Even among those with a severe disorder, only 24.3% reported seeking any such assistance. Needed are both effective interventions, including medications, for cannabis use disorders and increased patient motivation to seek such care.

Future work might benefit from a longitudinal design. While cross-sectional research such as the work by Hasin and colleagues (

5) helps to demonstrate important correlates of disorder, details about possible reasons for the associations (i.e., causal pathways) are better addressed in longitudinal studies. For instance, the recently launched National Institutes of Health Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) project proposes to study exposure to cannabis and other substances in repeated longitudinal examinations of children from preadolescence through their teen years. The ABCD study will include careful assessment of substance exposure along with psychosocial risk factors and mental illness, and so it will be well positioned to test the associations found by Hasin and colleagues. Second, examining whether and how changes in rates of cannabis use may inform the associations found by Hasin and colleagues remains a research challenge. It remains to be determined whether and how many of the associations are with cannabis use disorder or, more directly, with use of cannabis itself. Future research may be needed to consider whether the associations are fully explained by greater use of cannabis or by greater risk of a disorder, over and above the association with cannabis use per se.

Limitations notwithstanding, the Hasin et al. article should be received with enthusiasm for it is the first full epidemiological study of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder. The current findings supporting the dimensional approach in DSM-5 are particularly noteworthy in this context, for validation of the severity subtype may have significant implications for screening and treatment planning.

To capture their true significance, the findings from Hasin and colleagues (

5) should be analyzed in conjunction with the growing neurobiological evidence pertaining to the potential disruptive impact of cannabis use on brain development and mental health. We now know that the endocannabinoid system supports a core signaling mechanism that optimizes information processing and performance by fine-tuning the balance between inhibition and excitation throughout the brain (

Figure 1A). This mechanism is the key to understanding the endocannabinoid system’s involvement not only in psychiatric disorders but also in synaptic pruning and white matter development, two neurodevelopmental processes that are highly orchestrated and particularly active during adolescence. Exogenous administration of a cannabinoid, such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), perturbs normal signaling through the endocannabinoid system (

Figure 1B). Thus, repeated THC exposure may lead to persistent dysregulation in a broad range of neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine, serotonin, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and glutamate, across a vast network of circuits that rely on the endocannabinoid system to optimize developmental processes, adaptive behaviors, and overall brain performance (

8–

10). This helps explain some of the adverse consequences that have been associated with cannabis use, particularly when it is used regularly beginning in adolescence (

4).

Given the shifting cannabis legal and sociocultural environment, clinicians require accurate information to guide practice development. When seen in light of a growing body of neurodevelopmental work on the effects of cannabis on adolescent brain maturation processes, concerns about the potential harms associated with cannabis use and cannabis use disorder require public health vigilance. The findings from Hasin and colleagues help to address this gap and make a strong case for the need to enhance cannabis prevention and education efforts.