In this issue, Moriuchi et al. report on a fascinating study (

1) on a long-standing question: Why do children with autism look less at other people’s eyes, relative to typically developing children? The authors pit two theories against each other: gaze aversion and gaze indifference. Their results point to the latter, not the former, although the question of why remains.

One now quite old idea is that children with autism don’t see other people’s eyes as a window to the mind (

2). Their well-established difficulties in attributing mental states to other people may mean that they see other people’s eyes as parts within the face that move, but they struggle to interpret what these moving parts mean. Whereas the typical child pays a lot of attention to where others are looking because they understand that what someone looks at indicates their mental state (what that person is

interested in), children with autism may not appreciate the mentalistic significance of a person’s eyes. Nor might people with autism understand that a person’s eyes are a reflection of a range of mental states—cognitive, volitional, or affective.

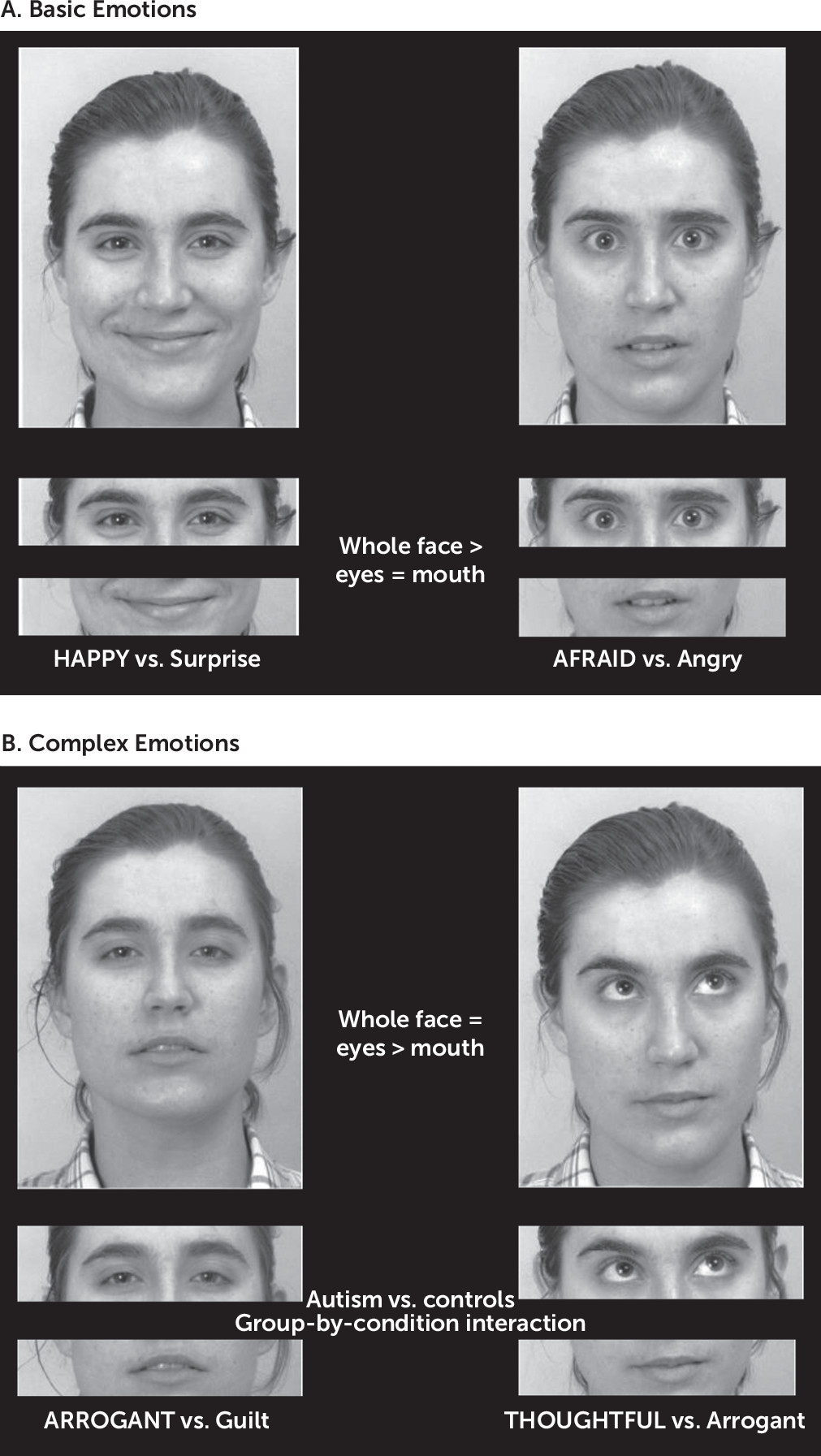

Consider how when we try to interpret a person’s basic emotions, such as

happy, sad, angry, afraid, disgust, or

surprise (

Figure 1A), people with or without autism score equally well if they are presented with the eyes or the mouth, although seeing the whole face leads to better performance. But when the task is to judge a

complex emotion, such as

arrogant, guilt, thoughtful, or

revenge (

Figure 1B), seeing the eyes alone results in as good performance as seeing the whole face, and both eyes and whole face are better than the mouth alone. Moreover, on such challenging tests, adults with Asperger’s syndrome show impaired performance when shown just the eyes.

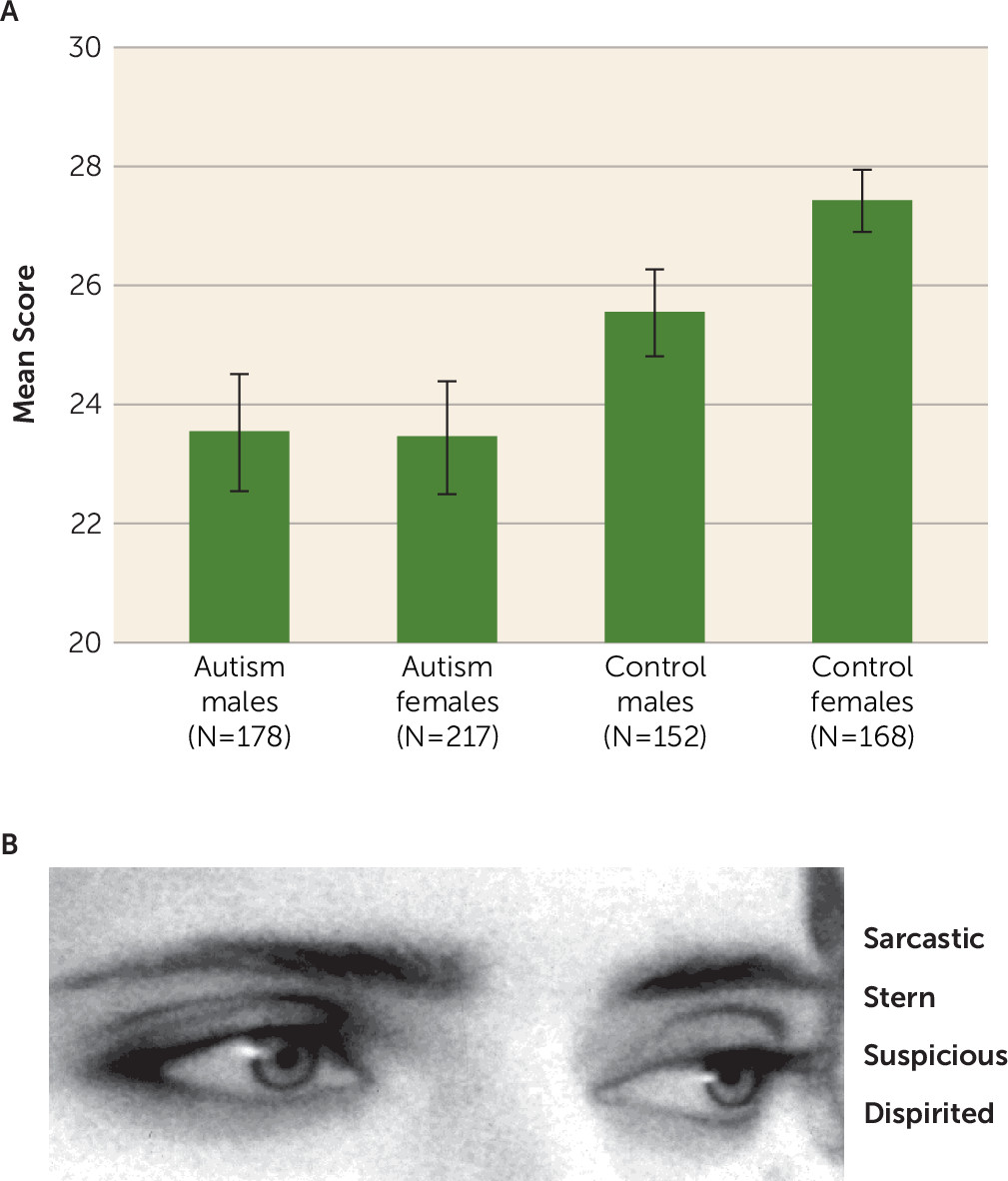

Using the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test, collecting data online, our group found that the impairment in autism is very clear, as is the sex difference (female superiority) in typical participants and the absence of any sex difference in autism (

4), confirming earlier studies (

5,

6) (

Figure 2).

Performance on the Eyes test is associated with activity in the amygdala and in the left inferior frontal gyrus (

7,

8); the female advantage on the test is associated with greater activity in the left inferior frontal gyrus, and the autistic deficit is associated with reduced activity in this same area. This deficit is also seen in parents of such children, suggesting that it arises for genetic reasons (

9,

10). Lesion studies confirm the importance of these brain regions in mentalizing the eyes (

11).

Candidate gene studies suggest that sex steroid pathway genes play a role in performance on the Eyes test (

12), and a whole genome study of more than 88,000 people (

13) found an association between performance on the Eyes test and chromosome 3p26.1 in typical females. The heritable aspect of mentalizing the eyes is apparent in at-risk infants who are siblings of children with autism (

14). A unique study (

15) also showed that performance on the Eyes test is negatively associated with levels of prenatal testosterone, which may explain the typical sex differences on this test. Administering testosterone to typical women reduces their scores on the Eyes test to typical male levels (

16) and reduces brain functional connectivity (

17). Administering the hormone oxytocin seems to have the opposite effect, improving scores on the Eyes test (

18). Naturally, individual differences in reading the mind in the eyes are not just a function of our biology, as postnatal social experience likely amplifies these prenatal determinants. For this reason, we should expect that impaired performance on this test might be observed in a range of clinical groups, not just in autism, for diverse reasons.