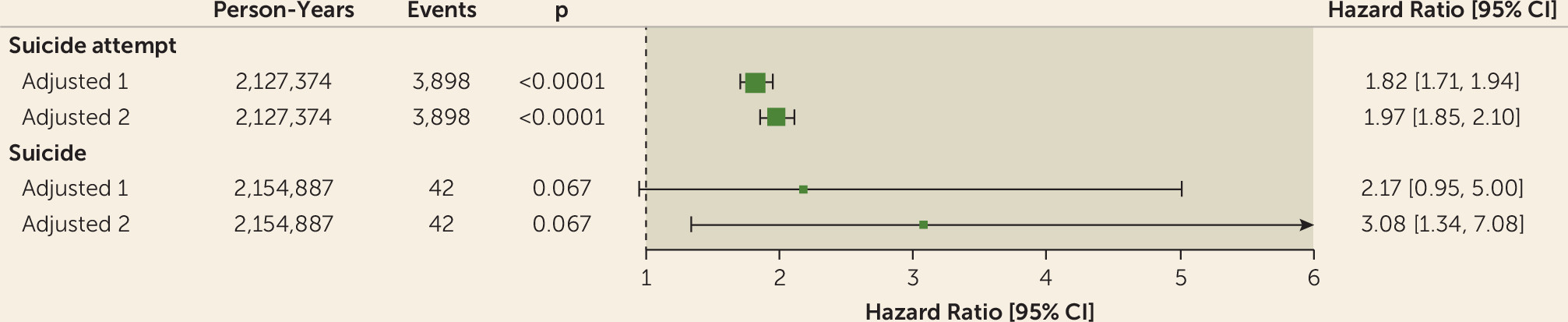

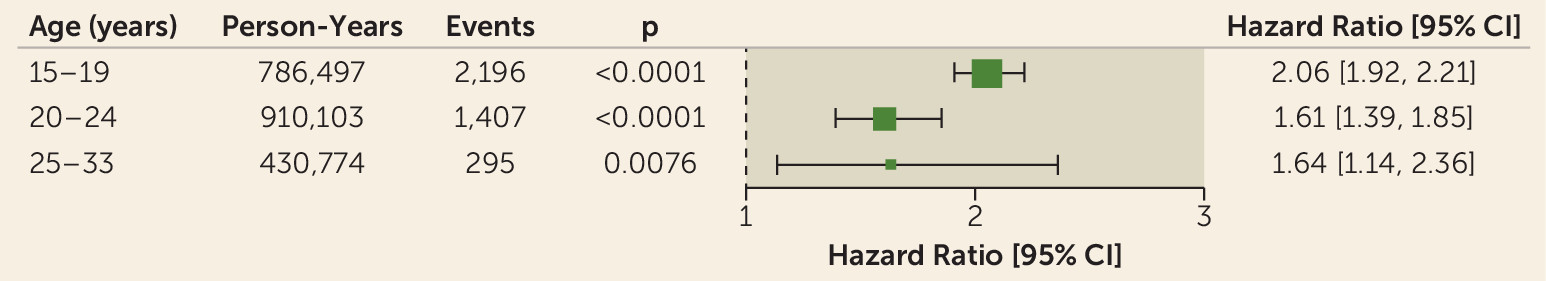

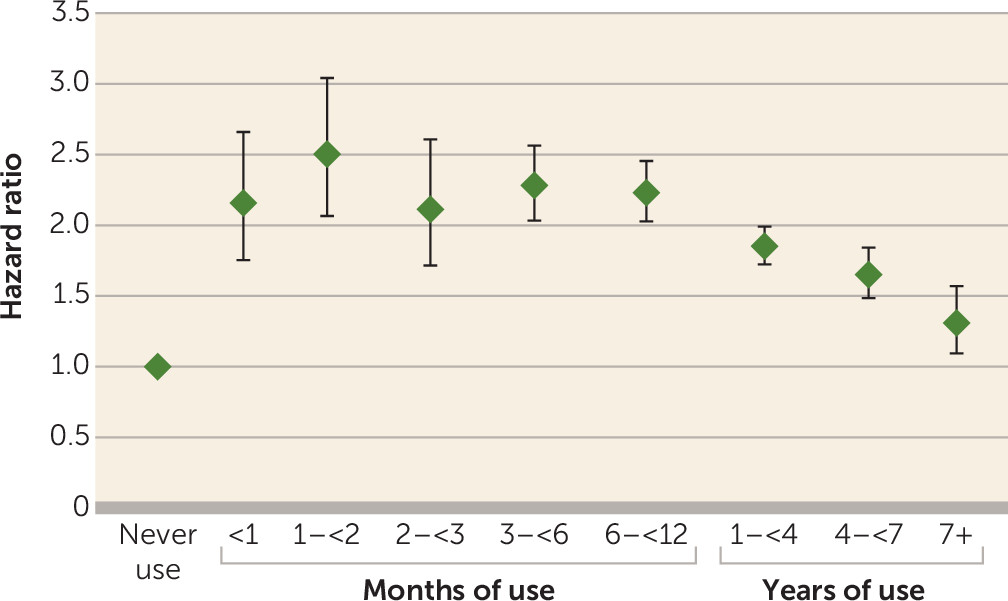

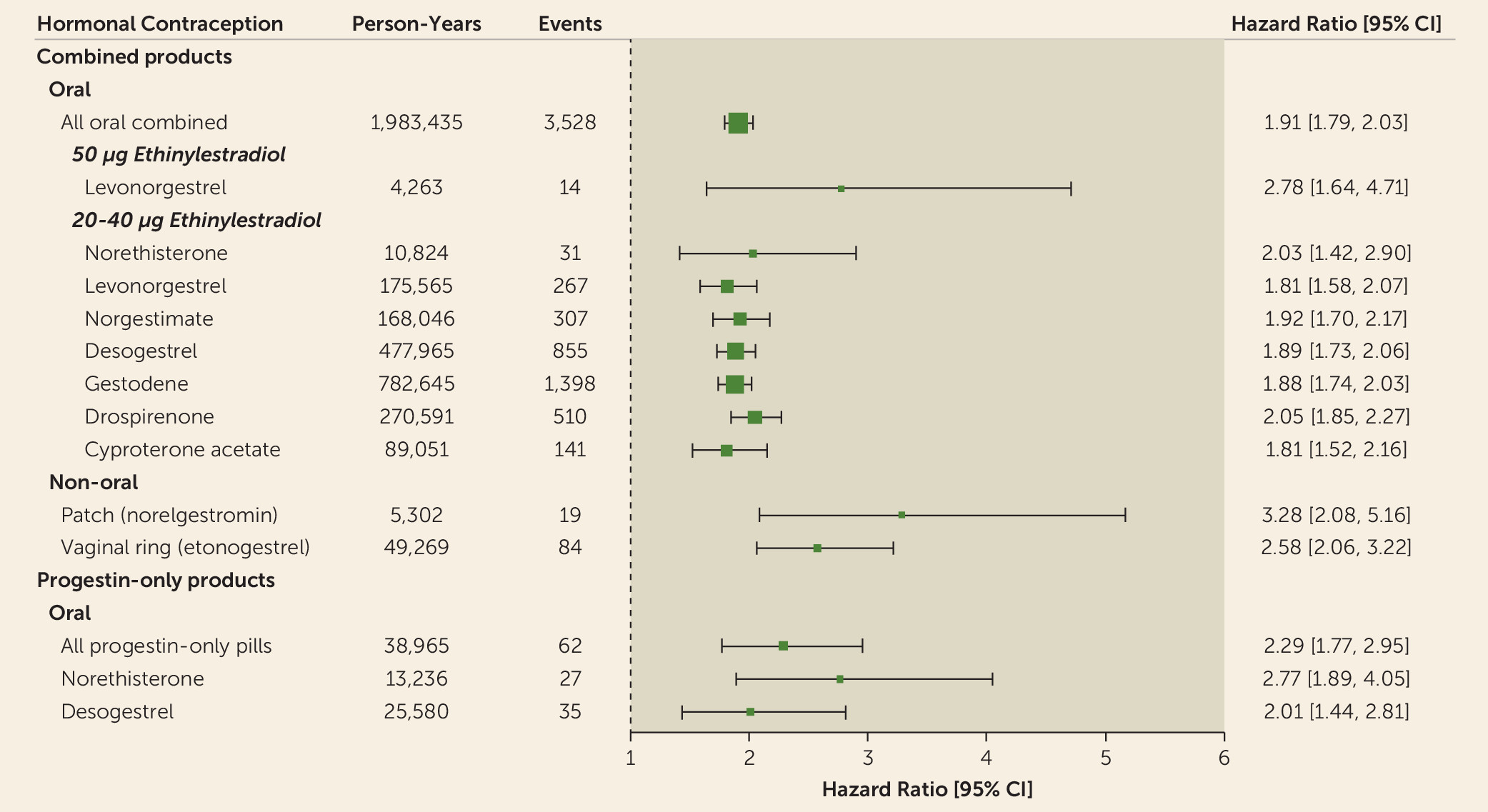

In women 15–33 years of age, hormonal contraceptive use was positively associated with a first suicide attempt, as compared with never-users. Adolescent women experienced the highest relative risks. Patch, vaginal ring, and progestin-only products were associated with higher risks than oral combined products, and a similar association was suggested for suicide. Compared with never use, the relative risk of suicide attempt rose twofold 1 month after initiation of hormonal contraceptive use, and the elevation in risk persisted with a decreasing trend after 1 year of use. The decrease in risk estimates for suicide attempt after 1 year of use was probably due to out-selection of women who develop adverse mood reactions after initiation of hormonal contraception. The women most sensitive to adverse mood reactions would thus be included in this former-user group. That circumstance is likely to explain why former use was associated with an increased risk of suicide attempt and suicide. This selection rather than their prior use of hormonal contraception more likely explains the higher relative risk of suicide attempts and suicide in former users.

Our data indicate that adolescent women are more sensitive than older women to the influence of hormonal contraceptive on risk of a first suicide attempt. This finding could be influenced by attrition of susceptible women, but also adolescent women are particularly vulnerable to risk factors for suicide attempt.

Several potential biological mechanisms have been suggested to explain how the two female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone are involved in the etiology of depressive symptoms (

15–

17). Because mood symptoms are a known reason for cessation of hormonal contraceptive use (

9–

11,

18,

19), cross-sectional studies are vulnerable to healthy-user bias, causing underestimation of a possible association between use of hormonal contraception and adverse mood reactions. Our recent study assessing the association between hormonal contraceptive use and risk of depression (

1) found a 70% higher risk of depression among users of hormonal contraception compared with never-users. A recent double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study (

20) found that women assigned to receive sex hormone manipulation with goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) experienced treatment-emergent subclinical depressive symptoms, and these symptoms were positively associated with the net decrease in estradiol levels.

Five studies (

4–

8) have assessed the association between use of hormonal contraception and risk of suicide (see Table S1 in the

data supplement). Four of the studies found no statistically significant association between use of oral contraceptives and risk of suicide compared with never-users. The risk estimates were, however, above unity in three of these studies (

5–

7), while one study comparing users of oral contraception with users of diaphragm or intrauterine devices (

4) found no elevation in the risk estimate. The other study, by Charlton et al. (

8), assessed the largest number of events (241 suicides) and found a statistically significant association of 1.41 (95% CI=1.05–1.87). We found no studies assessing the association between hormonal contraceptive use and suicide attempt.

Strengths and Weaknesses

We assessed a nonselected cohort of women living in Denmark turning age 15 during the period of 1996–2013. By using data from the Danish national registers, we were able to follow these women for a mean of 8 years with no follow-up loss. The large study population allowed assessment of rare events such as suicide and suicide attempts. The information on redeemed prescriptions of hormonal contraception was obtained through bar codes from all Danish pharmacies, eliminating recall bias. It also allowed daily assessment of hormonal contraceptive use with time-dependent variables. Considering that the women paid for the contraception, the proportion of women not using the redeemed contraception is assumed to be minimal; moreover, the majority of women had repeated prescriptions and were assumed to be users only during the time the redeemed prescription was valid.

By using the personal identification number assigned to all persons in Denmark, which allows reliable linkage of data between different registers, we were able to ensure that we detected incident events of suicide attempt. Because suicide attempts are recorded by public hospitals when patients are brought in, independently of the patient’s general practitioner and level of health insurance (all people in Denmark are covered by the public health insurance), it is unlikely that use of hormonal contraception would suggest better access to medical care and therefore a greater likelihood of a suicide attempt being recorded in the registers. Suicide attempts are known to be underreported (

21), but there is no reason to believe that the underreporting would be distributed differently among users and never-users of hormonal contraception, so this circumstance is not likely to affect the associations assessed.

The Danish Cause of Death Register contains information on all residents who have died in Denmark since 1970. The legal regulation of death certification mandates that any case of sudden and unexpected death must be reported to the police, and the death certificate may be issued only after a medicolegal examination has been conducted. For a few deaths it is not possible to determine whether or not it was a suicide, but in most cases it is evident.

A potential confounding factor might be the initiation of a sexual relationship, since we speculate that this could influence the risk of a first suicide attempt or suicide. But with the results stratified into age groups, we still see a significant association between use of hormone contraception and suicide attempt for women over age 20, the majority of whom have had their first sexual relationship. Moreover, many women initiate use of hormonal contraceptives for their noncontraceptive benefits—to alleviate menstrual pain, heavy bleeding, premenstrual syndrome, and acne. Thus, initiation of sexual activity is by no means always the reason for prescription. Indeed, 50% of young Danes report that they became sexually active before age 17, and, of these, 69% used a condom their first time (

22), which suggests that for many, sexual relationships start under use of contraceptive methods other than hormonal contraception. The reference group of never-users included women using a copper intrauterine device, women using barrier methods, and women relying on natural methods, such as rhythm methods and interrupted intercourse. Thus, this group also constitutes sexually active women. In short, sexual activity does not seem to be an important confounder for the relationship between use of hormonal contraception and suicide attempt or suicide.

The influence of postpartum depressions was diminished by censoring women temporarily during pregnancy and 6 months after delivery (

23,

24). We were not able to adjust for parental suicide/suicide attempt, which is a known risk factor for suicide or suicide attempt (

25,

26). To address this concern, we conducted a quantitative bias analysis to assess how strong and how common an unknown binary risk factor for suicide attempt should be if it explained our results. The analysis showed that the unknown risk factor should be very strong, with a high odds ratio for use of hormonal contraception and a prevalence in the study population of one-third, to be able to explain the observed association. We find it unlikely that there would be such a strong unmeasured confounder that at the same time had a prevalence of one-third in the population.

One could speculate on whether other risk factors for suicide or suicide attempt might be less common among the never-users of hormonal contraception, thereby potentially causing an overestimation of our results—for example, certain personality traits or religious subgroups causing both never use of hormonal contraception and a lower risk of suicide attempt (

27,

28). In the youngest group of women, the never-user group will include a majority who begin hormonal contraceptive use later in life and are thus similar to the user group with respect to unknown confounders, except for time-dependent confounders. In the older age groups, it is possible that women who are still never-users could differ more from the users. However, our results did not show stronger associations among the older women, which indicates that our results do not reflect overestimation due to a possible age-associated selection in the never-user group.

Our sample included only girls from the age of 15 who had no prior use of hormonal contraception. This was to avoid inclusion of a selected small group of girls who were sexually active at a very early age and received prescriptions for hormonal contraception for that reason. These girls might be at higher risk of adverse mood reactions. Women who might have a different hormonal contraceptive prescription pattern for other reasons (including various types of prior disease) that are potentially associated with the risk of adverse mood reactions or suicide attempts or suicide were excluded from the study.

Confounding by indication.

Another concern could be confounding by indication. By adjusting for polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis, we tried to account for the increased use of hormonal contraception in these groups as well as an increased risk for depression. We expect that institutionalized women and women with either mental retardation or more severe psychiatric pathology would be more likely to receive long-acting reversible contraceptive products, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate depot, an intrauterine device with levonorgestrel, or implants. Therefore, we find confounding by indication likely and decided to omit these three specific products from the results in

Figure 4. For the remaining products, women in these groups account for a vanishingly small fraction of all women using hormonal contraception. Women using combined hormonal contraception, progestin-only products, patch, or vaginal ring are generally assumed to have similar characteristics (

1), and the higher risk association among women using transdermal patch and vaginal ring compared with the corresponding pill is probably a question of dosage rather than of route of administration (

29). For these products, we found confounding by indication unlikely.

Mediation through psychiatric diagnoses.

Finally, in additional analyses we adjusted for any psychiatric diagnosis or use of antidepressants during follow-up and found a small influence with this adjustment on our results. The mediation analysis also establishes that the majority of the effect is not mediated through psychiatric diagnoses and antidepressant use, but this should be interpreted cautiously, as the mediator includes only diagnosed conditions before the suicide attempt, which will likely miss actual cases. This can be considered measurement error on the mediator, and it is well known (

14).

It is reasonable to assume that some psychiatric disorders were unknown and untreated before the suicide attempt and that the mediated proportion is therefore higher than estimated, as patients with an untreated illness will not be included in our registers.

It is also possible that hormonal contraception may have a direct influence on the neurotransmitter and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system involved in stress regulation and the neurobiology of suicidal behavior (

30). This assumption is supported by

Figure 3, which demonstrates a rapid increase in first suicide attempt after initiation of hormonal contraception.

Time-dependent confounders.

We cannot exclude individual time-dependent confounders, such as other major life events (bad sexual experience, break-up, divorce, etc.), which could potentially confound the key associations.