There is a lack of evidence-based pharmacotherapy for suicidal patients with major depressive disorder. The 26.5% increase in U.S. suicide rates from 1999 to 2015 (

1) underscores this treatment need. The American Psychiatric Association’s practice guideline on management of patients with suicidal behavior states that “evidence for a lowering of suicide rates with antidepressant treatment is inconclusive” (

2, p. 14). Standard antidepressants may reduce suicidal ideation and behavior in depressed adults, mediated by improvement in depressive symptoms, but this effect takes weeks (

3). Other somatic treatments with some evidence for antisuicidal effects include clozapine in schizophrenia (

4) and ECT (

5) and lithium (

6) in mood disorders.

Suicidal depressed patients need rapid relief of suicidal ideation. Depression remits in one-third or fewer patients, and fewer than half achieve even 50% relief with typical first-line medications (

7). Although suicidal behavior is usually associated with depression (

8), most antidepressant trials have excluded suicidal patients and did not assess suicidal ideation and behavior systematically, which has resulted in limited data on this topic (

9). Depression predicts suicide attempts via its effect on suicidal ideation (

10).

Ketamine, a drug with dissociative and glutamate receptor–blocking properties that was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1970 for anesthetic use, has recently become a target of research for its antidepressant effects, which occur within hours at subanesthetic doses (

11). Reports of reduction in suicidal ideation after ketamine infusion are promising, but the conclusiveness of results for major depression has been limited by measurement of suicidal ideation with a single item from a depression inventory (

12–

16), lack of a control group (

15–

17), use of a saline control (

12,

13), and use of samples with low levels of suicidal ideation (

16,

18) or mixed diagnoses (

19).

We conducted a randomized clinical trial of an adjunctive infusion of ketamine compared with the short-acting benzodiazepine anesthetic midazolam in patients with major depressive disorder who had clinically significant suicidal ideation, as assessed by score on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) (

20). The primary outcome measure was SSI score 24 hours after infusion. Other outcome measures included global depression ratings, clinical ratings during 6-week open follow-up treatment, and safety measures. Given ketamine’s dissociative effects, there is no ideal comparator, so, as in the trial by Murrough et al. (

21), we used midazolam because it is a psychoactive anesthetic agent with a similar half-life and no established antidepressant or antisuicidal effects. We hypothesized that ketamine would produce a greater reduction in suicidal ideation at 24 hours compared with midazolam.

Discussion

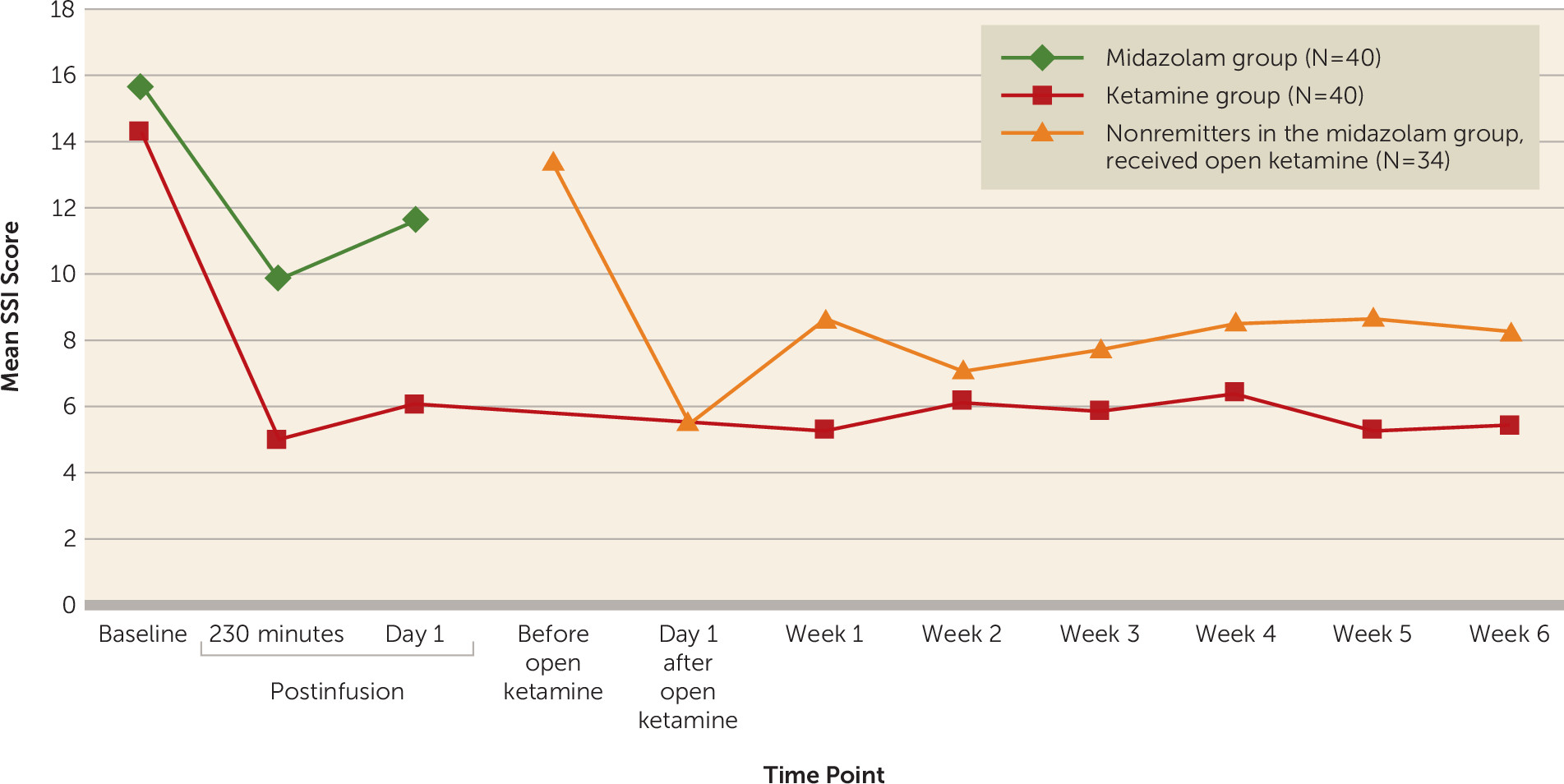

In major depression with clinically significant suicidal ideation, a single subanesthetic ketamine infusion, adjunctive to ongoing pharmacotherapy, was associated with a greater reduction in suicidal thoughts at day 1, the primary outcome measure, compared with midazolam control infusion. The adjusted mean difference of 4.96 points on the clinician-rated SSI, a Cohen’s d of 0.75, and a number needed to treat of 4 for response represent a medium-sized effect. Adverse effects—mainly blood pressure increase and dissociative symptoms—were similar to those reported in other ketamine studies (

37) and were mostly mild to moderate, and transient, typically resolving within minutes to hours after infusion. Improvement in suicidal ideation largely persisted during the 6-week period of uncontrolled observation, during which standard pharmacological treatments were also optimized.

To our knowledge, there is no established definition of a clinically meaningful reduction in score on a standard suicidal ideation scale. A prospective study (N=6,891) of patients with depressive disorders (

23) found that a baseline SSI score >2 predicted suicide during up to 20 years of follow-up. In a prospective study of 562 inpatients (64% with a mood disorder) who endorsed suicidal thoughts (

38), those who experienced a 50% reduction within 24 hours from a severe level (suicidal ideation “most of the time”) had one-third the risk of subsequent self-harm events during a mean length of stay of 24 days, compared with those whose suicidal thoughts remained elevated. Trials during recent decades show that the average advantage for antidepressant drug compared with placebo was 2 to 4 points on measures such as the 17-item HAM-D (

39). The United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence considers a standardized mean difference such as a Cohen’s d value ≥0.5, or a between-group difference of ≥3 points on the HAM-D or the BDI, to be clinically significant (

40). Together these data suggest that the advantage found in this study for reduction of suicidal ideation 24 hours after ketamine, compared with midazolam, is clinically meaningful.

Given concerns about ketamine’s 1- to 2-week antidepressant effect in previous studies (

11), it is notable that the improvement in suicidal ideation in this trial was largely maintained through the 6-week follow-up ratings. This may be partly explained by the fact that patients continued prior psychotropic medication, which was optimized after completion of day 1 postinfusion ratings. Our result is consistent with the Hu et al. trial (

41), in which patients with major depression who were randomly assigned to receive a single ketamine infusion on day 1 of escitalopram therapy experienced a faster response compared with patients who received a saline control infusion, and the benefits were maintained for 4 weeks.

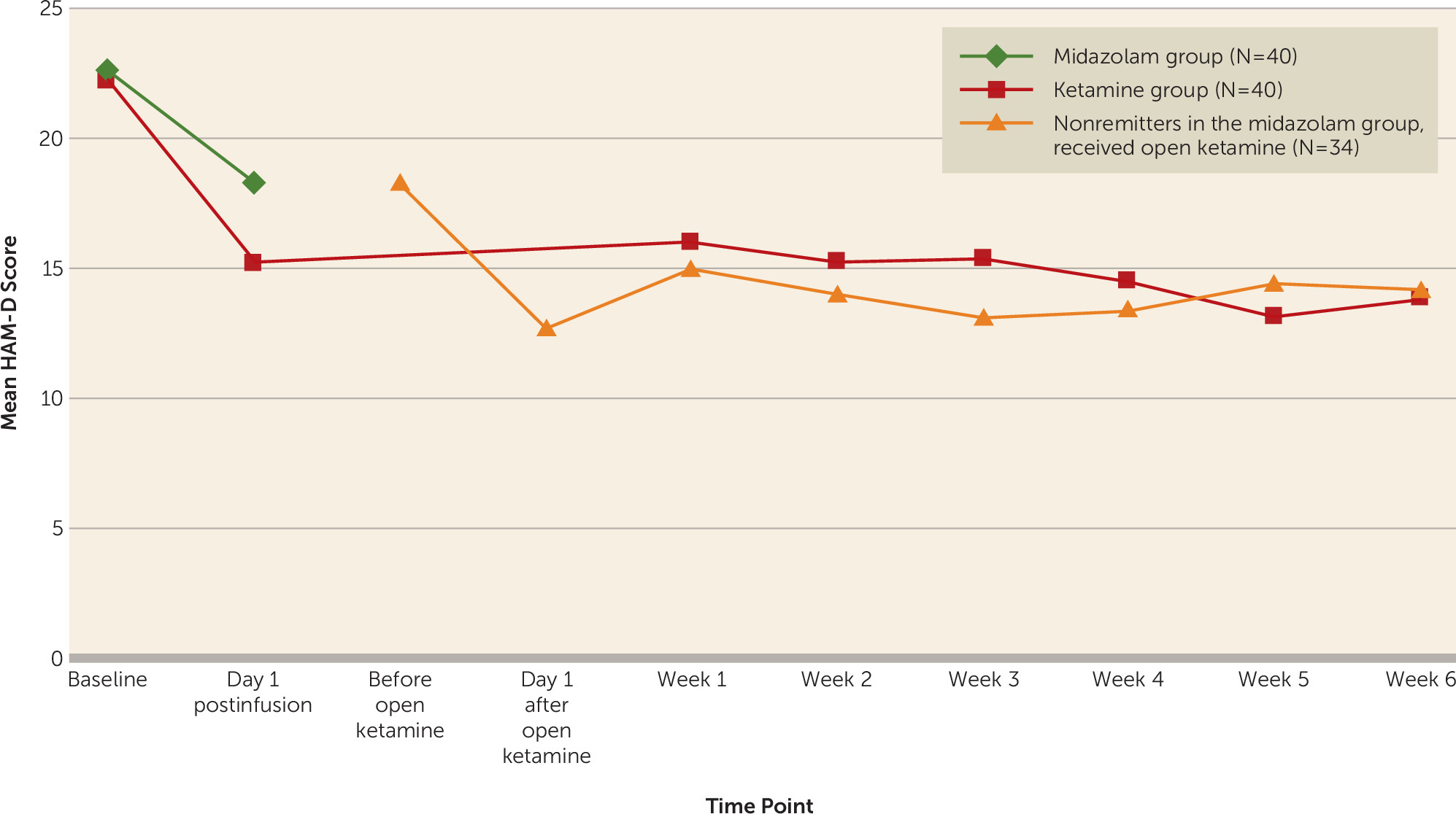

We found greater reductions in overall mood disturbance, depression, and fatigue, assessed with the POMS, on day 1 after ketamine compared with midazolam. The response rates we found for depression using the HAM-D and the BDI were surprisingly low compared with other randomized controlled ketamine trials (

42). Contributing factors may include concurrent antidepressant and other psychiatric medications, the effect of hopelessness as a feature of suicidal states, and the possibility that our sample was not treatment resistant and may have been more prone to midazolam placebo response.

The fact that the differential drug effect on global mood and depression was strongest for the POMS and the BDI may be related partly to their emphasis on subjective experience of core depressive symptoms, which correlate more strongly with suicidal ideation than do other symptom types (

43). A secondary analysis of adjunctive ketamine (N=14) found a reduction in suicidal ideation even when depression did not remit (

17). Ketamine is mechanistically distinct from currently approved antidepressants, its therapeutic effects possibly involving rapid synapse formation (

44). Our mediation model results suggest that its effects on depression and suicidal thoughts are at least partially independent.

The only other midazolam-controlled trial of adjunctive ketamine infusion using SSI score at day 1 as the primary outcome measure was a study of patients with mood and anxiety disorders (N=24) and a score ≥4 on the suicide item of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

19). Differences from our trial included mixed diagnoses, inpatient and outpatient settings, a higher midazolam dose (0.045 mg/kg), and use of the self-report SSI, which correlates >0.90 with the clinician-rated version that we used, although patients report higher scores than clinicians (

45). The results did not show a differential treatment effect on the primary outcome measure, but a difference favoring ketamine was found at 24 hours on the MADRS suicide item and at 48 hours on the SSI, which was no longer significant at 72 hours. The study did not find a differential effect on global depression ratings or correlations between changes in SSI and total MADRS scores.

A midazolam-controlled ketamine trial (

21) in treatment-resistant depression (N=73) found an 8-point advantage for ketamine on the primary outcome measure, MADRS score at day 1 (Cohen’s d=0.81; odds ratio for response=2.2). A subsequent analysis reported an advantage at day 1 for ketamine in reduction of a suicidal ideation index comprising the self-report SSI (mean baseline score=6) and suicide items from two depression scales, which was fully mediated by reduction in MADRS score minus the suicide item (

18).

We found stronger effects on suicidal ideation than on global depression compared with the latter trial (

21), although both studies involved patients with moderate to severe baseline depression severity according to MADRS and HAM-D guidelines (

46). Reasons for the difference may include our study design, in which we allowed patients to stay on their current, stable dosage of antidepressant medication instead of employing a medication washout during the week before the trial began. Fifty-four percent of our sample was taking antidepressant medication at baseline. Residual antidepressant effects from the concomitant medication in both treatment groups in our study may have diminished the antidepressant effect of ketamine. Another study difference was in the samples; the earlier study included patients with treatment-resistant depression, and our study included patients with clinically significant suicidal ideation.

Limitations of our study include the primary outcome measure of suicidal ideation as opposed to behavior. Suicide or attempts are more significant, but their low base rates, even in at-risk populations, mean that very large samples and long follow-up periods are required. Suicidal ideation is feasible and significant as an outcome measure, as clinicians assess it when evaluating need for hospitalization because it predicts suicide attempts (

47) and suicide (

23). Among patients in our study who had suicidal ideation at day 1, there was no differential drug effect on the SSI planning subscale, but greater improvement in the ketamine group on the suicidal desire and ideation subscale, which correlated with depression, hopelessness, and past suicide attempt in a study by Witte et al. (

35).

In our sample, there were more patients with borderline personality disorder in the ketamine group than in the midazolam group (28% compared with 8%). While there is no reason to think this would affect study infusion response in a particular direction, when it was included as a covariate it had little effect on the primary outcome measure. The higher rate of dissociative side effects with ketamine, found in other studies, makes midazolam an imperfect control (

21), but differences in rates of correct guesses on the blinded infusion drug were not statistically significant, among raters or participants. Other limitations include open-label treatment during the week 1–6 follow-up ratings, during which standard pharmacological treatments were optimized, and the small percentages of Hispanic and nonwhite participants.

In summary, in this randomized trial in suicidal depressed patients, a single adjunctive subanesthetic ketamine infusion was associated with a clinically significant reduction in suicidal ideation at day 1 that was greater than with the midazolam control infusion. In the context of standard, optimized treatment after the ketamine infusion, this improvement appeared to persist for at least 6 weeks. The clinical applicability of our findings was improved with infusion administration by a psychiatrist and without a medication washout, as has been done in some studies (

12,

13,

21). Research is needed to understand ketamine’s mechanism of action and to investigate strategies and safety of longer-term treatment.