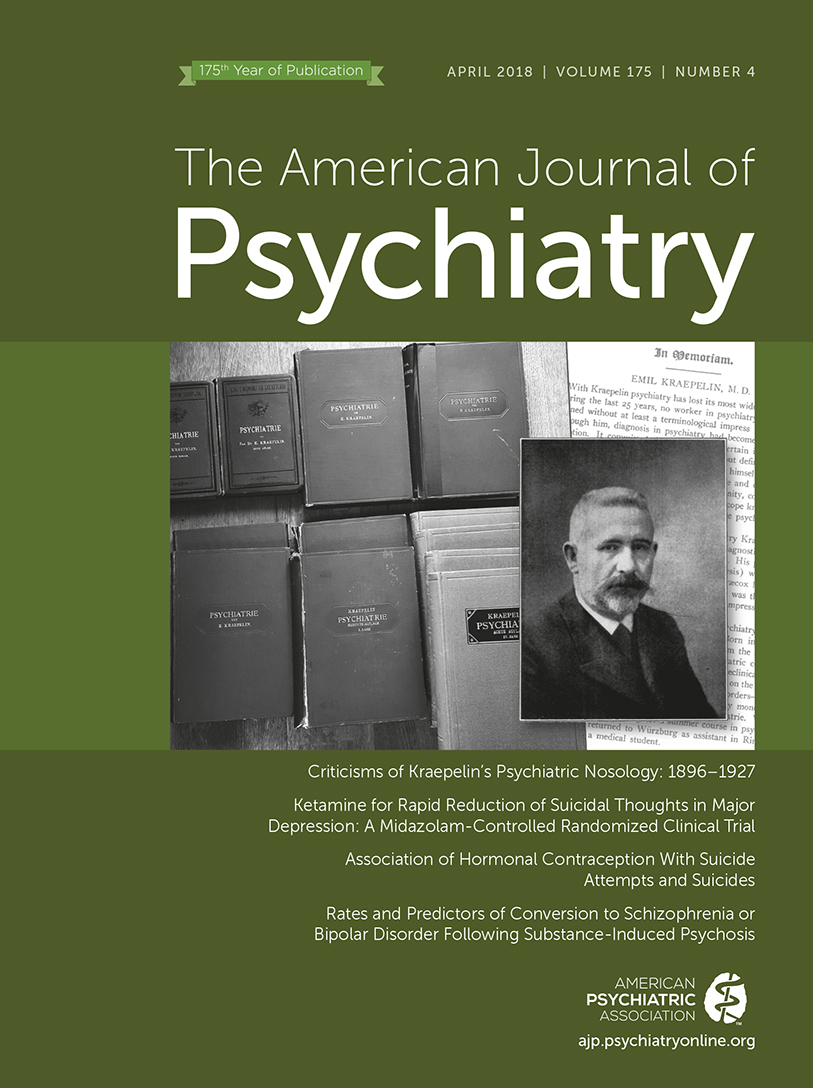

Kraepelin’s nosology of the major psychoses substantially influences psychiatric practice and research 120 years after its articulation in the 5th and 6th editions of his textbook

Psychiatry, published in 1896 and 1899 (

1–

4). After a period of idealization in the late 20th century, led by the neo-Kraepelinians (

5–

7), criticisms of his nosologic system have recently increased, driven by empirical developments in genetics (

8) and neuroscience (

9), as exemplified by the Research Domain Criteria proposed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (

10).

While many assume that Kraepelin’s nosology quickly gained worldwide acceptance early in the 20th century, in fact, from its inception, his diagnostic system met with substantial criticism. Our current debates about his system have, however, taken place largely independently of these earlier discussions. In this essay, we review the main criticisms of Kraepelin’s diagnostic system of the major psychoses published during his lifetime (1856–1926). Our goal is to historically contextualize and enrich our current debate.

Given the breadth of available material, our report is selective, relying on only six of Kraepelin’s critics: Adolf Meyer, Friedrich Jolly, Eugenio Tanzi, Alfred Hoche, Karl Jaspers, and Willy Hellpach. In early 20th-century psychiatry, other important contemporaries developed views that differed substantially from those of Kraepelin—for example, Carl Wernicke and Karl Bonhoeffer—but they never published explicit, in-depth evaluations of Kraepelin’s views. The choice of these six also covers the entire period of Kraepelin’s more mature work, allowing us to draw more general conclusions about the themes that provoked his critics. We summarize in

Table 1 the major critiques of Kraepelin’s nosology of each of our six critics and in

Table 2 brief biographical details about them. To demonstrate, on its 175th anniversary, the

Journal’s historical role as a forum of critical exchange, we pay special attention to relevant articles published in its pages.

Adolf Meyer (1896–1927)

Adolf Meyer (1866–1950) was an early and enthusiastic disciple of Kraepelinian psychiatry (

11–

13). In a letter to his fellow German expatriate, August Hoch, he wrote in 1896:

I am strictly Kraepelinian just now. I make my men swear by Kraepelin although I should like sometimes to do the swearing myself.… I must wean myself from my own elaborations before I can be as certain about things as a true pupil of a man should be (

14).

Meyer’s letter was written shortly after he had finished reading the seminal 1896 fifth edition of Kraepelin’s textbook. Meyer was visiting Kraepelin’s clinic in Heidelberg when the book was published, and he promptly reviewed it for the

American Journal of Insanity (the precursor to the

American Journal of Psychiatry) (

15;

16, p. 751). In his review, Meyer cast Kraepelin’s work as a “complete revolution” in psychiatric thinking (

15, p. 298). Most of Meyer’s praise was directed at Kraepelin’s exacting clinical methodology. He lauded Kraepelin’s “strictly clinical plan” (

15, p. 298) and proclaimed that psychiatrists were “deeply indebted” to him for having fostered “a sound enthusiasm for clinical studies” (

15, p. 302).

But looking beyond Kraepelin’s clinical methods to his nosology, Meyer’s review shows less enthusiasm. Upon his departure from Heidelberg, Meyer was already a “doubting Thomas” (

16, p. 752) about Kraepelin’s nosology, and his criticisms would be echoed by scholars on both sides of the Atlantic. Meyer characterized Kraepelin’s textbook as “decidedly dogmatic” (

15, p. 299) for its failure to engage the views of fellow psychiatrists. He described Kraepelin’s classification of all acute psychoses that terminate in dementia as “hypothetical” (

15, p. 300). Both the “domain of dementia praecox and catatonia” and the “periodic psychoses” (soon to be termed manic-depressive insanity) were “much broader” than generally accepted by contemporaries (

15, pp. 300–302). Meyer was especially concerned that nosology and nomenclature had eclipsed symptomatology: Kraepelin’s drive to organize his clinical evidence into “groups with specific basis, specific course, and specific termination is in many respects a problem, not a solution” (

15, p. 302).

Over time, Meyer’s views on Kraepelin evolved and became more incisive. In 1903, he published a lengthy critique of Kraepelin’s nosologic writings that was reviewed in the

American Journal of Insanity (

17,

18). In the 1920s, he articulated his disagreements with Kraepelin in two

American Journal of Psychiatry articles: “The Constructive Formulation of Schizophrenia” (

19) and the obituary he wrote upon Kraepelin’s death (

16). While Meyer appreciated Kraepelin’s focus on course of illness and outcome as a powerful simplifying principle, he was skeptical that his method could lead to the definition of distinct diseases. First, he questioned whether outcome deserved such emphasis in Kraepelin’s system. He wrote, “We may well be anxious to learn why deterioration should be considered the chief characteristic of a special group,” and he asked, “What are the fundamental traits claimed for dementia praecox apart from termination in a peculiar kind of mental weakness?” (

17, p. 670)

Second, he doubted Kraepelin’s assumption that course and outcome always reflected constitutional factors. He noted that Kraepelin seemed to assume “the often surprising independence of the whole [diagnostic] group from external influence, and insisted on the constitutional features in their etiology” (

17, p. 669). But clinical experience, Meyer argued, showed that social and environmental factors, as well as alcohol exposure and head trauma, could also have a substantial impact on illness course.

Third, he was skeptical that good and poor outcome classes of illness were etiologically homogeneous. Like some other earlier critics (

20, p. 846), he noted that in Kraepelin’s system, “Superficially very heterogeneous symptom complexes are thus brought under one head” (

17, p. 652). Meyer felt “decidedly averse to the frequent practice of throwing the cases from one pigeonhole to the other according to whether the outcome

looked promising or not, with the sacrifice of the facts as one actually found them” (

19, p. 357).

Ultimately, Meyer concluded that Kraepelin’s work contained “an exaggeration of the importance of the prognostic element of the disease concepts” (

17, p. 664). He wrote:

Kraepelin subordinates the symptom complex to a broader clinical, or as we might more properly say, to a more simple medical principle—that of evaluation of an outcome. To what extent has he created “diseases” or, at least, to what extent are his diseases distinct entities from the point of view of pathology…? [emphasis in the original]

Meyer believed that mental disorders could not be profitably studied with “an excessive emphasis on a prognostic classification” (

19, p. 357).

When reviewing the strength of Kraepelin’s nosologic conclusions, Meyer noted, in his cryptic writing style: “The dogmatism of disease entities and of definite disease processes underlying all their symptoms seems to meet [with] a certain antagonism” (

17, p. 666). That is, Kraepelin was overconfident that manic-depressive insanity and dementia praecox really reflected true “disease entities,” and he was ultimately the “last big creator of entities by classification” (

16, p. 755).

Another major concern of Meyer’s regarding Kraepelin’s nosologic work was that it ignored the “localization and the nature of the disease process” (

17, p. 653). In developing his diagnostic system, Kraepelin displayed no interest in the neurological substrate for these disorders. He was, in this approach, consistent with Kahlbaum and Hecker, whose work strongly influenced his own (

21).

Although Meyer had initially viewed Kraepelin as “the foremost psychological worker amongst alienists today” (

15, p. 298), he later argued that Kraepelin had ignored not only brain science, but psychological processes as well. Meyer noted that “Kraepelin’s observation of sequences refers … much more to elementary biological facts and is, as such, independent of psychological systems” (

17, p. 662). Kraepelin’s understanding of the progression of symptoms seemed to take no account of underlying psychological processes.

Furthermore, Meyer noted that while Kraepelin’s approach was “clinical,” he was only interested in aggregate features of groups of patients, not individual case histories. Unlike many of the great textbook writers in the late 19th century (Wernicke [

22], Clouston [

23], Krafft-Ebing [

24]), Kraepelin’s texts contained almost no detailed case histories (

16, p. 752). Instead, using his “index cards,” he often produced striking rapid-fire descriptions of particular symptoms. Meyer’s own use of “life charts” represented an attempt to account for patients’ individuality without abandoning nosology (

25).

Finally, Meyer had methodologic concerns about the empirical bases of Kraepelin’s clinical sample. It was relatively small (

17, p. 663) (compared, for example, with the 5,000 cases examined by Wernicke [

22]), and follow-up periods were often short.

Friedrich Jolly (1896)

The views expressed by Meyer in the

American Journal of Insanity and the

American Journal of Psychiatry echoed those of many European contemporaries. When Kraepelin first presented the results of his major nosologic research at the annual meeting of the German Psychiatric Association in 1896 in Heidelberg, just weeks after the publication of his seminal fifth edition of

Psychiatry (

1), his findings were roundly criticized by several professional peers, especially the director of Germany’s foremost psychiatric hospital in Berlin, Friedrich Jolly (1844–1904) (

20). In his review of Kraepelin’s textbook, Jolly articulated the first substantive critique of Kraepelin’s nosology and methodology (

26). Jolly agreed with Kraepelin that focusing on the cause and course of a disorder, rather than on the predominance of certain symptoms, was the key to establishing well-defined clinical forms. At the same time, however, Jolly criticized him for inconsistency in sometimes emphasizing course and sometimes symptoms. While Kraepelin seemed to have abandoned the well-established forms of melancholy and mania in favor of his new, broad, and course-based category of manic-depressive insanity, he retained, in this 5th edition, an independent category of involutional melancholia. Jolly criticized him for this:

It is not obvious why cases of melancholy that arise in climacterium should in fact be melancholy and not something else and why it suffices to characterize them primarily according to symptoms, whereas in other phases of life conditions that manifest an identical course should call for an entirely different interpretation (

26, p. 1004).

Jolly went on to argue that Kraepelin had entirely abandoned commonsense notions of periodicity by allowing acute episodes of depression separated by years or even decades to be labeled as “periodic.” Jolly doubted that Kraepelin’s understanding of periodicity was helpful and believed that it would sow confusion in daily practice:

Can one truly speak of periodicity if, over the course of a lifetime and due to a certain morbid precondition, melancholic states emerge from adequate internal and external causes? Above all, can one derive a more accurate … prognosis for a patient using this approach as opposed to more traditional ones? (

26, p. 1004)

Jolly also argued that Kraepelin’s overreliance on course had mistakenly led him to describe paranoia as a chronic, incurable disorder. Citing evidence that acute cases could end in recovery and that chronic cases could evolve from acute ones, Jolly rejected Kraepelin’s claim that course could be used to demarcate paranoia:

It’s not obvious why the basic principle that the chronic course determines eo ipso the nosologic status [

Gattungscharakter] of the disorder should hold. We know of many somatic illnesses that can have acute and chronic courses. And we have no difficulty understanding that the same disease process, depending on its intensity and the individual patient’s resilience, can sometimes result in complete remission and other times lead to lasting changes and defects (

26, p. 1005).

Accordingly, Kraepelin’s attempt to elevate prognosis to the most important diagnostic criteria for assessing paranoia was misguided. Jolly worried that it would lead practitioners astray: “If one wishes to split similar cases apart because they share no common prognosis, the result will be a Spinozian attenuation of diagnosis that will only lead to confusion in day-to-day practice” (

26, p. 1005).

Jolly did not limit this critique to paranoia. He proceeded to make the more general point that Kraepelin’s clinical methodology was fundamentally flawed because it “drew conclusions about the diagnosis based on the prognosis”:

The importance of the prognosis for the psychiatrist’s practical work is self-evident. But to group cases together because they prove to be incurable contradicts fundamental pathological principles (

20, p. 845).

Jolly’s critique was prescient and was subsequently echoed by other commentators. And nowhere were the differences of opinion more clear-cut than in debates about dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity. Critics charged that this dichotomy had severely compromised the legitimacy of traditional concepts such as paranoia, amentia, and melancholy and contributed decisively to an unwarranted burgeoning of Kraepelin’s two main categories:

The results of recent studies have always contributed to an

expansion of the categories: the autonomy of seemingly well-defined and generally accepted clinical pictures [

Krankheitsbilder] came under attack as they were incorporated into the large groups. Overestimating the importance of individual symptoms as the

hallmarks of certain illnesses has misled us to accept an inappropriate expansion of some categories and to group conditions together that have little more than superficial similarities in common with one another (

27, p. 569).

With respect to dementia praecox, critics objected to the idea that paranoid, catatonic, and hebephrenic forms were manifestations of the same disease. Above all, Kraepelin was criticized for abandoning the distinction that alienists had traditionally drawn between dementia praecox and catatonia and thereby incorrectly assuming that catatonic symptoms indicated dementia praecox. By attaching such prognostic and nosologic significance to catatonic symptoms, Kraepelin had downplayed the importance of other clinical signs, prejudiced the cases’ outcomes, and inflated dementia praecox to the point of being simply a “catatonic unity psychosis” that represented no improvement over “old psychiatric dogmatism” (

28, p. 261;

29, p. 17;

26, p. 1005;

30, p. 560). For years to come, numerous critics warned of the dangers of overdiagnosing dementia praecox: they insisted that catatonic symptoms had “no pathognomonic significance for dementia praecox” (

27, p. 574) and that many of the cases that ended in remission could be attributed to the misinterpretation of the diagnostic significance of those symptoms (

27;

31, p. 381).

The overdiagnosis of manic-depressive insanity also became a target of Jolly and other early critics (

31, pp. 282–283;

32, pp. 8–9;

33). In good part, they understood the burgeoning of manic-depressive insanity to be a derivative of the fact that for Kraepelin nearly all functional psychoses were either manic-depressive insanity or dementia praecox. Too often, cases that could not be diagnosed as dementia praecox were simply shifted across the diagnostic boundary to manic-depressive insanity. Indeed, in the words of one skeptic, practitioners fell into the grip of a “furor classificatorius” that drove them to diagnose their cases strictly as either one of the two large forms (

34, p. 20).

It is worth noting that Kraepelin conceded early on that his categories had become too large, but he insisted that his focus on course and outcome were the solution to this problem, not its cause (

35, p. 581). Significantly, by the 8th edition of his textbook, he accepted Jolly’s criticisms and expanded his view of paranoia to include “mild psychogenic forms of paranoia resulting in cure” (

36, p. 267).

Alfred Hoche (1912)

The next—and particularly sharp—critic of Kraepelin we examine is Alfred Hoche (1865–1943), focusing on his 1912 German essay, rendered twice into English (

39,

40); we utilize the Dening translation (

40).

Hoche correctly observed that Kraepelin’s textbooks represented only one in a long line of efforts to divide up major psychiatric syndromes into categories. Each category, he suggested, was nothing more than a passing fad. All such efforts were inherently implausible and only represented convenient catch basins for patients. Kraepelin’s efforts were necessarily futile because of the nonspecificity of any large syndromal category. In his acerbic tone, Hoche noted that the progress of psychiatry

does not fail to show the wave-movement that is usual in scientific discovery. There arose certain concepts for which the number of those supporting them grew rapidly only to diminish later.… The size, the peaks, and the tempo of these development waves really depend upon individual thinkers and academic departments. For some observers today the whole field … is divided up between dementia praecox and manic-depressive disorder. The magnitude of the concepts thus formed is in itself proof that a solution will not be found here (

40, pp. 335–336).

The success of Kraepelin’s paradigm resulted from his prestige and his skills of persuasion as a textbook writer rather than from strong empirical support, Hoche observed. Regarding Kraepelin’s diagnostic system, he wrote, “We are usually dealing with questions of belief rather that with something provable or readily ascertainable. The position is in fact essentially one that involves dogma” (

40, p. 338). Hoche dismissed the idea that because it was “new” and “exciting,” Kraepelin’s nosology must have been inherently better. Drawing on a metaphor to describe the creation of new psychiatric diagnostic systems, he wrote, “People are trying to clarify a cloudy liquid simply by pouring it from one container into another” (

40, p. 336).

Hoche was furthermore quite critical of Kraepelin’s concept of dementia praecox because of what he viewed as its implausible degree of heterogeneity. He remarked:

Under the blanket term dementia praecox are to be found curable, incurable, acute, and chronic conditions of every possible shade and hue as regards symptoms or that occur just once or recur (

40, p. 338).

Hoche criticized one of the logical foundations of what we have called the Kahlbaum-Hecker-Kraepelin paradigm (

21), namely, its reliance on parallels to diagnostic advances in general medicine. He believed such analogies to be flawed. He argued that the ways in which symptoms relate to underlying physiology was fundamentally different for psychiatry, where we have the complex mind-brain system influenced by biographical, social, and culture factors, than for general medicine, where we have infections producing fever, or too much thyroid hormone producing tremor and sweaty skin. He wrote:

Underlying all these busy efforts is the unassailable belief that even in the field of psychiatry it must be possible to discover clearly defined, pure, and uniform forms of illness. This is a belief that is carefully nourished by the analogy to physical medicine without any consideration being given to the fact that the nature of the relationships between symptom and anatomical substrate … affords no basis for any comparison between them (

40, p. 336).

Finally, Hoche attacked the overreliance of the Kahlbaum-Hecker-Kraepelin paradigm on general paresis of the insane (calling it progressive paralysis) because of its striking atypicality. He wrote:

Progressive paralysis was the foremost example of a successful and definitive delineation of syndromes.… The success achieved here has perhaps produced unfortunate side effects by fostering the illusion that something similar might soon turn up again (

40, p. 335).

Karl Jaspers (1913)

In the first edition of his famous

General Psychopathology (

Allgemeine Psychopathologie), our fifth critic, Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), began by taking aim at the idea—central to Kraepelin’s nosology—of true “natural disease entities [

natürliche Krankheitseinheiten]” (

41, p. 257). Such entities could, according to Kraepelin, be established if the evidence indicated a common etiology, a common fundamental psychological form, a common development, course, and outcome, and eventually a common histopathological basis.

But in Jaspers’s view, Kraepelin had found no such entities. Even that most paradigmatic of psychiatric disorders, general paresis of the insane, remained a “purely neurological and cerebro-histological entity” (

41, p. 260). There was nothing characteristic about the psychological symptoms of patients afflicted with general paresis of the insane, as they could exhibit depressive, manic, or demented syndromes. Furthermore, the cause and anatomic basis of both dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity remained unknown; and depending on whether one emphasized course and outcome, as Kraepelin had, or the psychological symptoms, as Eugen Bleuler had, the differential diagnosis of the disorders became tenuous at best. The boundary between the two disorders had swung in recent years like a pendulum without producing any nosologic clarity (

42, p. 475).

Jaspers also attacked the assumptions that undergirded Kraepelin’s clinical research (

41, pp. 261–262). Kraepelin understood his research to be preparatory to postmortem, cerebro-pathological evidence. He argued that clinical observation of mental phenomena and the course of patients’ illnesses enabled him to posit characteristic types of disorders that would then be confirmed on the basis of histopathological examination. But Jaspers claimed that this assumption was incorrect. For one, history had shown that cerebral processes with somatic manifestations had always been identified on the basis of physical examination rather than psychopathological theorizing. And conversely, whenever well-defined brain mechanisms had been identified, patients exhibited all manner of psychopathological symptoms. That is, a one-to-one relationship between the underlying etiology and the resulting clinical syndrome was rarely found. In addition, the psychological and psychopathological evidence produced by Kraepelin’s own clinical research was not diagnostically reliable. Even in cases of general paresis of the insane, Kraepelin’s clinical diagnoses had been unreliable. And if his clinical approach could not reliably diagnose known somatic disorders, Jaspers asked, how could it be expected to find and distinguish yet unknown diseases?

Jaspers’s critique of Kraepelin’s clinical research also extended to several conceptual issues (

41, pp. 262–264). First, any assessment of all the clinical evidence could not possibly culminate in “finding” clearly defined diseases. Instead, it would produce only different “types” of disorders that, in individual patients, were characterized by transitional or borderline symptoms. Second, Jaspers disputed Kraepelin’s claim that common outcomes could serve as evidence for common disease. Echoing the views of Karl Bonhoeffer (

43), Jaspers insisted that different organic disorders often produced the same states of dementia and that the same disorders could generate different outcomes. Jaspers conceded that in some cases a morbid process was essentially incurable, but he insisted that there were no means of distinguishing these cases from others that, depending on specific circumstances, could be either curable or not. Third, Jaspers maintained that the concept of a “disease entity” [

Krankheitseinheit] could never be definitively established for a given case because it impossibly presumed complete knowledge of the case. Citing the German philosopher Kant, Jaspers insisted that disease entities were not attainable goals but rather regulative ideas that served to orient scholarly research. He gave Kraepelin credit for recognizing that the idea of disease entities helped spawn productive lines of psychiatric research, but he warned of the danger of assuming that nosologic categories such as dementia praecox or manic-depressive insanity represented objectively true, natural entities. While such categories guided an important “synthetic impulse” (

41, p. 263), we must also recognize the limitations of that impulse: if, as in the case of Kraepelin’s dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity, the categories became too inclusive, they would forfeit their diagnostic usefulness. Jaspers believed that Kraepelin’s emphasis on studying the entire course of patients’ illnesses through extensive catamnestic and anamnestic examinations indulged his taxonomic inclinations and proved incapable of adequately guarding against overinclusive categories.

In later editions of his

General Psychopathology, Jaspers also criticized Kraepelin’s textbook because, although the best of its era, it too often indulged in an “endless mosaic” (

42, p. 478) of clinical observations without generating a coherent clinical picture of a single patient.

Willy Hellpach (1919)

Throughout his career, Kraepelin had been an outspoken advocate of the new science of experimental psychology (

44,

45). In fact, readers of the

American Journal of Insanity likely first associated Kraepelin’s name with experimental psychology rather than psychiatric nosology (

46,

47). As a result, his textbook also attracted the attention of contemporary psychologists and social scientists. Aside from the sociologist Max Weber (

48), the most prominent of these was certainly Willy Hellpach (1877–1955). In 1919, Hellpach reviewed the eighth edition of Kraepelin’s textbook (

49), focusing on an evaluation of the success of Kraepelin’s efforts to incorporate the insights of experimental psychology into psychiatry. He concluded that this effort had failed to live up to expectations. Kraepelin’s textbook proved that for psychiatry “almost nothing important had been achieved using experimental psychological methods, whereas great strides had been made without it and with wholly different methods” (

49, p. 340). The fault lay partly in the priorities of Kraepelin’s own clinical research, especially its emphasis on course and outcome, because the experimental methods he used could only capture current mental states and not the transformations between those states. While Hellpach was not the first to criticize Kraepelin’s experimental methods (e.g.,

50, p. 250; and

48), his critique was especially powerful for coming in 1919, by which time the early promise of the 1890s that experimental methods would substantially enhance diagnostic practice and help clarify disease course and etiology had clearly not been fulfilled.

More importantly for our purposes, however, the same clinical approach that Kraepelin’s experimental methods were designed to enhance had become an object of criticism. Echoing the views of Jaspers, Hellpach cited contemporary research on paralysis to illustrate this point. Over the short span of 15 years, thanks chiefly to the introduction of the Wassermann reaction test and Hideyo Noguchi’s discovery of the

Treponema pallidum bacterium (

51), the diagnosis of general paresis of the insane had been transformed from a psychopathological to a physiopathological procedure. As a result, interest in the psychological symptoms of paralysis had declined markedly. Indeed, many of the disorder’s characteristic psychological symptoms had been reduced to mere “epiphenomena of a cerebro-pathological process.” In his textbook, Kraepelin had failed to account for this decline in the pathognomonic relevance of his clinical evidence. Far from culling his textbook of outdated psychological observations, Kraepelin had piled on further clinical evidence. His textbook had fallen victim to “casuistry, that great disease of contemporary German medicine, which had accumulated an enormous, inert mass of symptomatological evidence in need of a thorough purging” (

49, p. 344;

30, p. 561).

Hellpach attributed this failing to the “naive realism” and positivistic ethos of Kraepelin’s research (

52,

53). The revolutionary insights of the 1890s had been swamped in subsequent decades by the evidence he had gathered as a “busy bee” clinician. The danger, Hellpach argued, was that the profuse abundance of clinical evidence hid important pathognomonic distinctions. It made it seem as though the diverse symptoms of any given clinical case were much like those of any other case. By piling symptom upon symptom in the interest of greater subtlety and objectivity, Kraepelin had implicitly suggested that clinical evidence was more important than it actually was. Students could therefore hardly avoid the dubious conclusion that nosology was nothing more than purely “specialized fiddling” (

49, p. 344) with the evidence and that, in their day-to-day practice, psychiatrists were reduced simply to diagnosing madness.

Discussion

Far from being universally accepted, Kraepelin’s nosologic system was the target of a series of pointed critiques prior to his death in 1926, many of which anticipated current concerns. In this section, we emphasize six major points made by our critics, noting current parallels. First, Kraepelin radically redrew the nosologic boundaries of the major 19th-century psychiatric disorders. Many commentators remained unconvinced that this was a step forward. His new categories of dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity were too broad and too heterogeneous. Some made more specific points. Jolly criticized the inclusion of all catatonic syndromes in dementia praecox. Tanzi argued that melancholia fit poorly into manic-depressive insanity. Concerns about the heterogeneity of our major psychiatric disorders, especially schizophrenia, remain common (

54–

56). The proper nosologic place for catatonia has been hotly debated (

57). Evidence in favor of a sharp division between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder has been increasingly questioned (

8,

58). Congruent with Kraepelin’s concept of manic-depressive insanity, DSM-III and DSM-IV categorized major depression as part of “affective disorders” and “mood disorders,” respectively. However, in accord with Tanzi’s objections, in DSM-5, major depression was moved into its own “depressive disorders” category.

Second, several commentators attacked Kraepelin’s emphasis on course of illness. Jolly’s argument—echoed by Hoche—was that, in general medicine, the same pathophysiological process can, depending on level of host resistance, result in brief or chronic illness. Meyer noted that social and psychological factors also have an impact on course. For general paresis of the insane, which was used as a paradigm by Kraepelin and his predecessors (

21), diagnosis nearly always predicted prognosis. But general paresis of the insane was more the exception than the rule and therefore constituted a poor paradigmatic choice for Kraepelin, who emphasized the congruence between symptoms and course. For general paresis of the insane, a deteriorating course was associated with widely divergent symptoms (

59). Recent work has questioned whether the courses of schizophrenia and psychotic mood disorders are as different as Kraepelin claimed (

60).

Third, Hoche asserted that Kraepelin’s influence was based on the high quality of his textbook and his academic prestige, not on empirical evidence. Kraepelin’s ability to model his work on etiologic advances in general medicine was, our critics argued, more at the level of metaphor than rigorous scientific method. This charge would have rankled Kraepelin given his empirical ethos and willingness to reevaluate his nosology in the light of new clinical evidence (

45). But perhaps ironically, regardless of Kraepelin’s skeptical approach to his own work, within a few years of its publication, his diagnostic system was already being described as psychiatric dogma, or in more modern terms, as “reified.” Questions about the quality of the empirical grounding of Kraepelin’s diagnostic system have continued to this day. Within the evolving DSM nosology, increasing efforts have been made to move away from a prestige-driven “expert consensus” toward a rigorous empirical grounding of psychiatric nosology, but how far that can practically go remains controversial, given the limits of available data (

61,

62). Indeed, critics have argued that a major problem with our Kraepelin-influenced DSM nosology is its excess reification (

63,

64).

Fourth, Meyer and Jaspers both noted that the individual and their life story are missing from Kraepelin’s nosologic writing. In Kraepelin’s desire to categorize and exemplify particular symptoms and signs, the patient seems to have been lost. While a diagnostic and a clinical evaluation are not the same thing, especially as interpreted by the neo-Kraepelinians (

6), Kraepelin’s approach to psychiatric illness can be seen as losing the patient’s “life story.” As illustrated by the heated debate over the bereavement exclusion criterion for major depression in DSM-5 (

65), we continue to struggle with how to balance the need for diagnostic objectivity and empathic understanding (

66).

Fifth, Hellpach emphasized Kraepelin’s failure to incorporate experimental psychology into his nosologic framework. The enthusiasm for the new psychological methods with which Kraepelin had begun his career (

45) was not, in the end, justified, as his many psychological experiments did not have a meaningful impact on his nosologic system. The potential influence of psychological constructs on psychiatric research has been amply demonstrated by the NIMH Research Domain Criteria project (

10).

Finally, Jaspers provided perhaps the deepest critique of Kraepelin’s enterprise, questioning the viability of defining natural disease entities within psychiatry because of the many-to-many relationship between brain pathology and psychiatric symptoms. This has remained a central concern within psychiatry and is reflected in continuing debates about the feasibility of hard reductionist models for psychopathology that could support molecular-etiologic models for psychiatric disorders (

67,

68). There remain tremendous difficulties in understanding how to identify stable causal pathways from molecular processes to our patients’ phenomenal experiences (

69,

70).

Thoughts on Kraepelin From Two Other Major American Figures: Cowles and Sullivan

Focusing on Kraepelin’s critics should not obscure the historical fact that many contemporaries expressed far less critical views. Indeed, it would be mistaken to assume that our critics typify the reception of Kraepelin’s work. Before closing, and in the spirit of this anniversary issue, we therefore turn briefly to two other prominent and perhaps more representative figures in American psychiatry who commented on Kraepelin in these pages: Edward Cowles (1837–1919) and Harry Stack Sullivan (1892–1949). Cowles, who developed an important biological research program in psychiatry at McLean Hospital in the 1890s (

71), wrote favorably of Kraepelin in an 1899

American Journal of Insanity article entitled “Progress in the Clinical Study of Psychiatry” (

72):

The latest and most original contribution is that of Kraepelin in his studies and clinical methods which are giving us perhaps the most illuminating conceptions of insanity that we have yet received as explaining principles.… It is one of the merits of Kraepelin, and an evidence of the soundness of his teachings, that others as well as himself, in working out the principles he lays down, must advance from one formulation of tentative conclusions to another in progress toward the truth. Nothing could be more stimulating and encouraging in our work.… [B]esides the symptoms of any present attack, we [must] take into account the course of the disease through the patient’s life-time together with the final outcome of the disease (

72, pp. 111–112).

Indicative of Kraepelin’s waning influence by the 1920s, Sullivan provided more critical comments in a 1925 article in the

Journal entitled “The Peculiarity of Thought in Schizophrenia.” Along with Jolly and Meyer, he argued that, contrary to Kraepelin’s general approach, the course of illness can often be influenced by autobiographical factors:

It is the life situation of the patient that determines the prognosis. What he has derived from his forebears, his life experience, and that which befalls him during his illness … these only, are … the determining factors which make … for benignity or malignancy (

73, pp. 21–22).

He also argued, consistent with Meyer and Jaspers, for the need to study the life course of individual patients. In contrast to Kraepelin’s syndromal diagnostic approach, Sullivan argued that “anything of value in our work comes from the intimate and detailed study of particular individuals” (

73, pp. 22–23).

Conclusions

In this and our two previous articles on Kraepelin (

21,

45), we have attempted to outline, for modern psychiatric audiences, the context in which Kraepelin’s work arose, its substantial and sometimes underappreciated strengths, and its potentially important limitations. We hope thereby to provide a historical background to the continuing debates about the value of Kraepelin’s nosologic system, which continues to substantially shape our field. We consider it beyond doubt that Kraepelin’s diagnostic paradigms have been very fruitful for the young science of psychiatry, but we also agree that their ultimate value remains to be determined.

In this article, necessarily more negative in tone than our previous two essays, we reviewed prominent concerns expressed about Kraepelin’s diagnostic work within his lifetime. We would emphasize three overarching conclusions. First, Kraepelin’s system was the subject of vigorous debate from its inception, and it was never uniformly accepted as psychiatric orthodoxy. Second, most of our current concerns about his work have roots in these earlier discussions. Third, ongoing arguments about the value of Kraepelin’s nosology would be enriched by a deeper appreciation of their historical contexts. As authoritative as Kraepelin’s voice was—and remains today—his was only one of many voices. Paying greater attention to those voices, many of which have reverberated throughout the pages of the American Journal of Psychiatry over the past 175 years, would be well repaid with a deeper understanding of the fundamental conceptual challenges to the clinical and scientific field of psychiatry.